Introduction: An Artist of Heart and Hearth

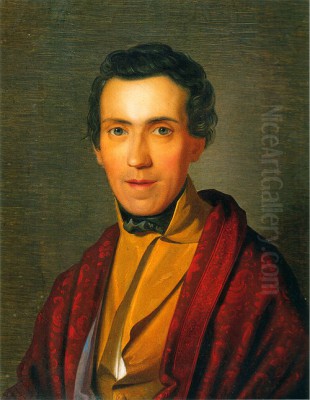

Adrian Ludwig Richter stands as one of the most beloved and representative artists of 19th-century Germany. Born in Dresden in 1803 and passing away there in 1884, his life spanned a period of significant cultural and social transition. Richter navigated the currents of late Romanticism and the burgeoning Biedermeier era, becoming a master painter, etcher, and, perhaps most famously, an illustrator whose works captured the German popular imagination. His art, characterized by its gentle sentiment, idyllic portrayal of nature and domestic life, and deep connection to folklore and literature, offered a comforting vision of harmony and simple virtues during a time of change. While primarily known for his charming woodcut illustrations, his paintings and etchings also reveal a sensitive observer of landscape and human interaction, securing his place as a key figure in German art history.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in Dresden

Ludwig Richter, as he was commonly known, was born into an artistic environment on September 28, 1803, in Dresden, the capital of Saxony. His father, Carl August Richter, was a respected engraver and etcher. This familial connection provided the young Adrian with his earliest artistic training and exposure to the techniques of printmaking, which would become central to his later career. Under his father's guidance, he learned the fundamentals of drawing and engraving, developing a keen eye for detail and line work from an early age.

Dresden itself was a vibrant cultural center, boasting rich art collections and an active community of artists. Growing up in this atmosphere undoubtedly nurtured Richter's artistic inclinations. His formal education included studies, but his practical training began in earnest within his father's workshop. This early immersion in the craft of engraving laid a solid foundation for his technical skills.

In 1820, at the age of 17, Richter accompanied his father on a journey that broadened his horizons beyond Saxony. They traveled through France, visiting Strasbourg and potentially other areas. This trip offered him his first significant exposure to different landscapes and artistic traditions outside his immediate surroundings, planting seeds for his later extensive travels and his deep appreciation for landscape representation. These formative years, grounded in craft and stimulated by the cultural milieu of Dresden and early travel, set the stage for Richter's development as an artist deeply rooted in German tradition yet open to external influences.

The Transformative Italian Sojourn

A pivotal period in Richter's artistic development was his extended stay in Italy from 1823 to 1826. Funded possibly by a patron or through his own means, this journey was almost a rite of passage for Northern European artists seeking inspiration from classical antiquity and the sun-drenched Mediterranean landscape. Richter immersed himself in the artistic environment of Rome, the epicenter for many German artists abroad.

In Rome, he encountered the legacy of classical art and the High Renaissance, but perhaps more importantly, he connected with the contemporary community of German artists residing there. This included figures associated with or influenced by the Nazarene movement, such as Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld and potentially encountering the spirit, if not the direct circle, of artists like Friedrich Overbeck and Peter von Cornelius, who sought a revival of religious and historical painting inspired by early Renaissance masters like Raphael and Dürer.

Richter also came under the influence of landscape painters working in Italy, most notably Joseph Anton Koch. Koch, an Austrian painter considered a bridge figure between Neoclassicism and Romanticism, was renowned for his heroic Italian landscapes that combined meticulous observation of nature with idealized compositions. Richter studied Koch's approach, learning to structure landscapes while imbuing them with atmospheric depth and Romantic sensibility. He spent considerable time sketching in the Roman Campagna and traveling south towards Naples, absorbing the unique light, topography, and rustic life of the Italian countryside.

This Italian experience profoundly shaped Richter's landscape painting. While he retained a fundamentally German sensibility, his compositions gained breadth, his handling of light became more nuanced, and his appreciation for the harmonious integration of figures within the landscape deepened. The journey provided him with a wealth of motifs and a more sophisticated understanding of landscape art that he would later adapt to German settings. One notable work reflecting this period is his painting Storm in the Sabine Mountains, now housed in the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, which captures the dramatic atmosphere of the Italian landscape, albeit filtered through his characteristically composed style.

Return to Saxony: Meissen and the Dresden Academy

Upon returning from Italy in 1826, Richter sought to establish his career back in his native Saxony. His skills, refined by his Italian studies, soon found application. In 1828, he secured a position as a designer at the renowned Royal Porcelain Factory in Meissen, near Dresden. He also taught at the factory's drawing school during this period. This role required him to adapt his artistic talents to the demands of decorative arts, likely honing his sense of composition and clarity suitable for reproduction.

His reputation continued to grow, and a significant advancement came in 1836 when he was appointed professor at the prestigious Dresden Academy of Fine Arts (Hochschule für Bildende Künste Dresden). He took charge of the landscape painting studio, succeeding Johan Christian Dahl, a prominent Norwegian Romantic painter who had spent much of his career in Dresden. This appointment solidified Richter's position within the German art establishment.

As a professor, Richter influenced a generation of students. His teaching likely emphasized careful observation of nature, solid compositional principles derived from his classical and Italian studies, and the infusion of sentiment and narrative characteristic of German Romanticism and Biedermeier aesthetics. He became a respected figure in the Dresden art scene, associating with fellow artists like the Romantic painter Ernst Ferdinand Oehme. His long tenure at the Academy, lasting until his retirement from teaching duties in 1877, underscores his importance as both a creator and an educator within the Saxon art world.

Artistic Style: The Confluence of Romanticism and Biedermeier

Richter's art is most accurately understood as occupying the intersection of late German Romanticism and the Biedermeier style. While influenced by the high ideals and emotional intensity of early Romantics like Caspar David Friedrich and Philipp Otto Runge, Richter's work generally adopts a gentler, more accessible, and domestically focused tone.

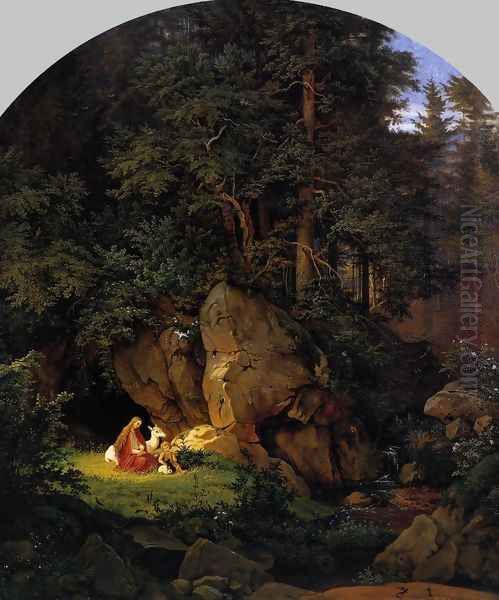

Romanticism in Richter's work is evident in his deep love for nature, often depicted as a benevolent and harmonious setting for human life. He shared the Romantic fascination with folklore, medieval legends (as seen in his Genoveva watercolor), and national identity. His landscapes, particularly those of the Elbe River valley and Saxon Switzerland, are imbued with a poetic sensibility, though they rarely reach the sublime or melancholic heights of Friedrich's canvases. Instead, Richter emphasizes the picturesque and the idyllic.

The Biedermeier aspect of his style emerged strongly from the 1830s onwards, reflecting the cultural values of the German middle class during the relatively stable period between the Napoleonic Wars and the revolutions of 1848. Biedermeier art and culture prioritized the domestic sphere, family life, simple pleasures, sentimentality, and a degree of withdrawal from political turmoil. Richter excelled at capturing this ethos. His works often depict charming scenes of family outings, village festivals, children at play, and quiet moments of contemplation within cozy interiors or pleasant natural surroundings.

His style is characterized by clarity, meticulous detail, and a strong narrative element, particularly in his illustrations. He was influenced by earlier German graphic artists like Daniel Chodowiecki, known for his detailed depictions of 18th-century life, and perhaps indirectly by the linear precision of Albrecht Dürer's prints. Richter's compositions are typically well-ordered, his figures clearly delineated, and his emotional range tends towards warmth, gentle humor, and quiet contentment rather than high drama or profound angst. This blend of Romantic themes with Biedermeier sensibility made his art immensely popular and relatable to a broad audience.

The Celebrated Illustrator: Visualizing German Culture

While Richter was an accomplished painter, his most widespread fame and enduring legacy arguably rest on his prolific work as an illustrator, primarily through woodcuts and etchings. Beginning seriously in the late 1830s, he produced thousands of illustrations that became ubiquitous in German households, shaping the visual imagination of generations. His skill lay in translating literary themes and everyday scenes into clear, charming, and memorable images.

His woodcut technique, often executed by skilled engravers based on his drawings, was perfectly suited for mass reproduction in books and periodicals. The style was direct, linear, and easily readable, yet filled with carefully observed details of costume, setting, and human expression. He possessed an extraordinary ability to capture the essence of a story or poem in a single image, often infusing it with warmth and gentle humor.

Richter provided illustrations for a vast range of German literature. He became particularly associated with fairy tales and folk legends. His illustrations for the Brothers Grimm's Fairy Tales and Ludwig Bechstein's collections are iconic, defining the visual appearance of characters like Snow White and Hansel and Gretel for many Germans. He also illustrated Johann Karl August Musäus's Volksmärchen der Deutschen (German Folk Tales), producing memorable images like Rübezahl Appears to a Mother in the Form of a Charburner.

Beyond folklore, he illustrated classic German poetry and prose, including works by Schiller (such as Das Lied von der Glocke - The Song of the Bell) and Goethe (notably Hermann und Dorothea, a bourgeois epic perfectly suited to Richter's Biedermeier sensibility). His illustrations for collections like Beschauliches und Erbauliches (Contemplative and Edifying) and numerous children's books further cemented his reputation as an artist who spoke directly to the heart of the German family. These illustrations were not mere decorations; they became integral parts of the reading experience, contributing significantly to the popularity and cultural resonance of the texts themselves.

Notable Paintings and Etchings

Although overshadowed in popular fame by his illustrations, Richter's paintings and etchings constitute a significant body of work that reveals his skills as a landscapist and observer of life. His paintings often depict themes similar to his illustrations but realized with the full resources of color and oil paint.

One of his most celebrated paintings is Bridal Procession in a Spring Landscape (sometimes titled Spring Morning). Completed around 1847, this work epitomizes his mature style. It shows a cheerful wedding party winding its way through a lush, sunlit landscape, embodying the Biedermeier ideals of community, tradition, and harmony with nature. The painting was highly acclaimed, winning a gold medal at the Paris World Exhibition in 1855 and acquired by the Dresden Gemäldegalerie Neue Meister, confirming his status on an international stage.

His Italian experience continued to resonate in works like Storm in the Sabine Mountains, mentioned earlier, which showcases his ability to handle more dramatic natural phenomena within a structured composition reminiscent of Joseph Anton Koch. However, his primary focus remained the German landscape, particularly the areas around Dresden, such as the Elbe valley and the picturesque rock formations of Saxon Switzerland. These landscapes are typically populated with small figures engaged in simple activities, reinforcing the theme of peaceful coexistence between humanity and nature.

Richter was also a skilled etcher, carrying on the tradition inherited from his father, Carl August Richter. His etchings often explore landscape themes with a fine, detailed line. A Study of the Watzman Landscape, for example, demonstrates his ability to capture the specific character of a famous Alpine view through the etching medium. His watercolor Genoveva, depicting the medieval legend of Genevieve of Brabant, shows his engagement with Romantic historical themes and his delicate handling of the watercolor medium. These works, while less known than the woodcuts, demonstrate the breadth of Richter's technical abilities and artistic interests beyond illustration.

Contemporaries, Context, and Connections

Adrian Ludwig Richter operated within a rich and complex network of artistic currents and personalities in 19th-century Germany. His career intersected with various movements and figures, highlighting his position within the broader art historical landscape.

His style finds close parallels with that of Moritz von Schwind, another major figure of German late Romanticism, particularly known for his fairytale illustrations and lyrical, narrative compositions. Both artists shared a penchant for folklore and a charming, accessible style, though Schwind perhaps leaned more towards the purely imaginative and decorative.

Within Dresden, Richter was part of a generation that followed the high Romanticism of Caspar David Friedrich and Johan Christian Dahl. While respecting these predecessors, Richter and contemporaries like Ernst Ferdinand Oehme forged a path that integrated Romantic sentiment with the more grounded, intimate focus of the Biedermeier era. His teaching role at the Academy placed him in a position of influence over younger artists.

His time in Rome connected him with the Nazarene circle (Overbeck, Schnorr von Carolsfeld, Cornelius) and the landscape tradition of Joseph Anton Koch. Although Richter did not fully adopt the religious or historical focus of the Nazarenes, their emphasis on clear drawing and narrative likely resonated with him. Koch's influence on his landscape composition was more direct and lasting.

Richter's work can be contrasted with other major developments in German art. The Düsseldorf School of Painting, with artists like Carl Friedrich Lessing and the Achenbach brothers (Andreas and Oswald), often focused on more dramatic historical scenes or highly detailed, sometimes more overtly Romantic or early Realist landscapes. Later in Richter's life, the rise of Realism, exemplified by Adolph Menzel in Berlin, marked a shift towards unidealized observation and contemporary urban or industrial subjects, moving away from the idyllic world Richter typically portrayed. Figures like Alfred Rethel, known for his powerful historical woodcuts, offer another point of comparison in the realm of graphic art, though Rethel's style was generally more monumental and dramatic. Richter's enduring appeal lay precisely in his consistent dedication to a more harmonious, sentimental, and popularly accessible vision.

Later Years, Legacy, and Critical Reception

Adrian Ludwig Richter remained active as an artist for most of his long life. He continued to teach at the Dresden Academy until 1877 and produced illustrations well into his later years. However, his creative output eventually ceased due to failing eyesight, a condition that forced him to stop working around 1874. He spent his final decade in retirement in Dresden, where he died on June 19, 1884. He was buried in the Neuer Annenfriedhof cemetery in Dresden.

Richter's legacy is substantial, particularly in the realm of illustration and popular visual culture in Germany. During his lifetime and for decades after, he was immensely popular, arguably one of the most beloved German artists. His illustrations adorned countless books, calendars, and household items, shaping the German perception of their own folklore, literature, and idealized national character. His vision of a peaceful, harmonious, family-centered life resonated deeply during the Biedermeier period and beyond, offering an image of stability and tradition.

His influence extended through his teaching and his widely disseminated prints. He helped define the visual language of German Romanticism's later phase and the Biedermeier era. His works became synonymous with a certain kind of German sentimentality and gemütlichkeit (coziness, contentedness).

Critically, Richter's reputation has seen fluctuations. While universally acknowledged for his charm, technical skill (especially in drawing and printmaking), and historical importance, some later critics viewed his work as overly sentimental, conservative, and lacking the profound depth or innovative spirit of artists like Friedrich or Menzel. His avoidance of social commentary or the harsher realities of life, and his adherence to an idealized vision, have been seen by some as limitations.

However, contemporary reassessments often appreciate Richter more fully within his historical context. His art is recognized as a genuine expression of the Biedermeier worldview and a masterful example of narrative illustration. His ability to connect with a broad audience and his role in visualizing key aspects of German cultural heritage are undeniable. His works continue to be studied and exhibited, valued for their artistic quality, their historical insight, and their enduring, gentle charm.

Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of Richter's World

Adrian Ludwig Richter remains a significant figure in 19th-century German art, a bridge between the high ideals of Romanticism and the intimate focus of the Biedermeier era. As a painter, he created sensitive landscapes and genre scenes that celebrated the harmony between nature and simple human life. As an etcher and watercolorist, he demonstrated technical finesse across various media. But it was as an illustrator, particularly through his woodcuts, that he achieved his greatest fame and left his most indelible mark on German culture.

His thousands of illustrations for fairy tales, poems, and popular literature became defining images for generations, embodying a vision of Germany characterized by idyllic nature, strong family bonds, and cherished traditions. While perhaps lacking the revolutionary impact of some contemporaries, Richter's art possessed a unique warmth, clarity, and narrative power that resonated deeply with the public. He captured the spirit of his time, particularly the Biedermeier desire for peace, order, and domestic happiness. His work continues to offer a window into the sensibilities of 19th-century Germany and retains a timeless appeal through its gentle beauty and heartfelt depiction of a world imbued with simple grace and quiet joy.