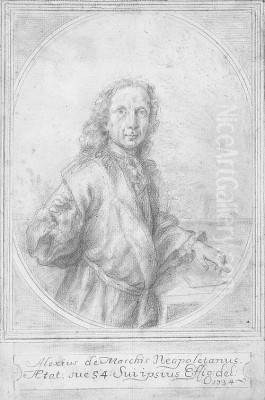

Alessio De Marchis stands as a significant, albeit sometimes controversial, figure in the landscape of 18th-century Italian art. Born in Naples in 1684 and passing away in Perugia in 1752, his life spanned a period of transition in artistic sensibilities. Primarily celebrated as a landscape painter, De Marchis carved a unique niche for himself, becoming particularly renowned for his dramatic depictions of fire, alongside more tranquil pastoral scenes. His work is characterized by a dynamic handling of paint, a keen sensitivity to light and shadow, and a style that absorbed influences while retaining a distinct personal signature. His career took him from his native Naples to the bustling artistic center of Rome and later to cities like Perugia and Urbino, leaving behind a body of work that continues to intrigue art historians and collectors alike.

Early Life and Roman Formation

Born into the vibrant cultural milieu of Naples in 1684, Alessio De Marchis's early artistic inclinations soon led him towards Rome, the undisputed heart of the European art world at the time. It was in Rome that his formative training truly took shape. Sources indicate that he spent a crucial period working in the studio or gallery associated with Philipp Peter Roos, a German painter highly active in Italy and known affectionately as Rosa da Tivoli. Roos himself was celebrated for his pastoral landscapes often populated with animals, and his influence, particularly perhaps in the depiction of natural textures and a certain atmospheric quality, can be discerned in De Marchis's developing style.

Beyond the direct tutelage or association with Roos, De Marchis deeply absorbed the influence of earlier masters who had defined the landscape genre. Chief among these was Gaspard Dughet, also known as Gaspard Poussin, the brother-in-law of the great Nicolas Poussin. Dughet’s classically structured yet often atmospheric and somewhat wild landscapes, depicting the Roman Campagna, provided a powerful model for many artists, including De Marchis. This Roman environment, steeped in the legacy of artists like Claude Lorrain and Salvator Rosa, offered a rich tapestry of stylistic approaches to landscape painting, from the idealized and serene to the dramatic and untamed, all of which would feed into De Marchis's own artistic synthesis.

Development of a Distinctive Style

Alessio De Marchis forged an artistic style marked by its energy and its dramatic interplay of light and shadow (chiaroscuro). His brushwork is often described as lively, vivid, and applied with a certain rapidity, sometimes resulting in forms with slightly blurred or undefined outlines. This technique contributed to the dynamic feeling present in many of his canvases, whether depicting tranquil countryside or raging fires. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the effects of light, rendering the subtle shifts of daylight across a landscape or the stark, flickering illumination cast by flames.

His palette and technique show a fascinating blend of influences. The structural underpinnings might owe something to the Roman school, perhaps inherited through Dughet, providing a sense of order and composition. However, his handling of light and color, sometimes described as having a certain "viscosity" or richness, can also suggest an awareness of Venetian painting traditions, known for their emphasis on colorito (color and painterly application) over disegno (drawing and design). Some critics note characteristics reminiscent of the 17th century (Seicento), likely referring to the Baroque era's dynamism and emotional intensity, which De Marchis carried into the 18th century.

His approach often involved strong contrasts, not just between light and dark, but also in the juxtaposition of detailed passages with broader, more suggestive strokes. This created a visual vibrancy and prevented his works from becoming static representations. He excelled at conveying depth and perspective in his landscapes, drawing the viewer's eye into the scene through carefully constructed spatial arrangements and the skillful modulation of light and atmosphere.

Landscapes: Nature Observed and Transformed

The core of De Marchis's oeuvre lies in landscape painting. He frequently depicted the Italian countryside, capturing pastoral scenes populated with figures, often peasants or travelers, engaged in daily life. Works like his Paesaggio campestre con scena di mietitura (Rural landscape with harvest scene) exemplify this aspect of his production. These paintings showcase his ability to observe nature closely, rendering trees, foliage, earth, and sky with sensitivity. There's often a feeling of harmony and a connection between the human figures and their natural surroundings.

Unlike the purely idealized Arcadian visions of some predecessors like Claude Lorrain, De Marchis's landscapes often possess a more grounded, sometimes even rustic, quality. While influenced by the classical landscape tradition established by artists such as Nicolas Poussin and Gaspard Dughet, De Marchis infused his scenes with a distinct energy. His interest lay not just in representing the topography but in capturing the feeling of the landscape – the quality of the light, the movement of the clouds, the texture of the earth.

His approach can be seen as part of a broader evolution in landscape painting during the 18th century. While still rooted in Baroque traditions, his work sometimes hints at a burgeoning pre-Romantic sensibility. This is evident in the emphasis on atmosphere, the dynamic brushwork, and an emotional resonance that goes beyond simple depiction. He seemed less concerned with mythological or historical narratives within the landscape (though he did paint such scenes) and more focused on the inherent drama and beauty of nature itself, sometimes peaceful, sometimes turbulent.

The Drama of Fire: A Defining Theme

While a capable painter of serene landscapes, Alessio De Marchis gained particular notoriety, both during his lifetime and posthumously, for his depictions of fire. This thematic focus set him apart from many contemporaries. He seemed fascinated by the destructive yet visually spectacular power of flames, capturing scenes of burning buildings, rural fires, and even mythological conflagrations with dramatic intensity. His paintings of fire are characterized by flickering light, deep shadows, billowing smoke, and a sense of chaos and urgency.

One notable example is his Enea e Anchise in fuga dall'incendio di Troia (Aeneas and Anchises fleeing the fire of Troy). This work, based on Virgil's Aeneid, allowed him to combine a classical subject with his penchant for dramatic pyrotechnics. The focus is often as much on the swirling flames and illuminated smoke engulfing the legendary city as it is on the fleeing figures. He masterfully used the light of the fire to model forms, create stark contrasts, and heighten the emotional impact of the scene.

This specialization earned him the somewhat sensational epithet "il Pittore incendiario" (the incendiary painter). His skill in rendering the visual effects of fire – the intense heat suggested by the colors, the dynamic movement of the flames, the way light reflects off surfaces amidst the surrounding darkness – was widely recognized. These works showcased his technical virtuosity and his ability to handle complex compositions filled with movement and high drama, distinguishing his output from the more tranquil landscapes produced by contemporaries like Andrea Locatelli or Francesco Zuccarelli.

The Haystack Incident: Artistry and Controversy

Perhaps the most famous, or infamous, story associated with Alessio De Marchis concerns an incident that allegedly occurred during his time in Rome. According to several biographical accounts, De Marchis, driven by an obsessive desire to study the effects of fire from life for his paintings, deliberately set fire to a haystack or barn in the countryside. His intention was purely artistic – to observe the colours, the light, and the movement of the flames firsthand to achieve greater realism in his work.

However, his artistic experiment reportedly went awry or was discovered, leading to his arrest and imprisonment. While the exact details and the duration of his confinement vary in different accounts, the story itself became legendary. It painted a picture of an artist so consumed by his craft that he transgressed societal norms and laws. This anecdote undoubtedly contributed to his reputation as an eccentric and perhaps even dangerous figure, the "pyromaniac painter."

While some commentators criticized his recklessness, others saw the incident, and the resulting paintings, as evidence of his profound commitment to capturing the raw truth of his subject matter. The dramatic fire effects in his paintings were sometimes attributed, rightly or wrongly, to these direct, albeit illicit, observations. Whether entirely factual or embellished over time, the story of the burning haystack remains inextricably linked to De Marchis's biography, highlighting the passionate, perhaps even obsessive, nature of his artistic pursuits and adding a layer of notoriety to his name.

Career Beyond Rome: Perugia and Urbino

While Rome was central to his formation and early career, Alessio De Marchis did not remain there permanently. He eventually moved to Perugia, a prominent city in Umbria, where he continued to work and where he ultimately passed away in 1752. His presence in Perugia suggests he found patronage and opportunities outside the highly competitive Roman art market. The specific reasons for his move are not always clearly documented, but it marks a later phase in his life and career.

During his career, De Marchis also undertook commissions in other locations. Notably, he is recorded as having worked in Urbino, a city with a rich artistic heritage dating back to the Renaissance. There, he received a significant commission from Cardinal Annibale Albani, a member of a powerful ecclesiastical family and a noted patron of the arts. De Marchis was tasked with creating decorative paintings for the Cardinal's palace. This commission indicates that De Marchis had achieved a level of recognition and respect sufficient to attract high-profile patrons outside of Rome.

His work for Cardinal Albani likely involved landscape frescoes or large-scale canvases appropriate for palace decoration, further demonstrating his versatility within the landscape genre. This period highlights his integration into the established systems of artistic patronage of the time, working for influential figures in the Church hierarchy. His activity in Perugia and Urbino underscores that his reputation extended beyond Rome and that he was an active participant in the broader artistic life of central Italy during the first half of the 18th century.

Wider Artistic Context and Connections

Alessio De Marchis operated within a rich and evolving artistic landscape. His direct link to Philipp Peter Roos (Rosa da Tivoli) placed him within a lineage of Northern European artists who came to Italy and specialized in pastoral scenes. His profound debt to Gaspard Dughet connected him to the Franco-Roman tradition of classical landscape painting, itself deeply influenced by giants like Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, whose idealized visions of the Roman Campagna had set the standard in the previous century.

However, De Marchis's style also showed affinities with other trends. His Neapolitan origins might connect him, at least spiritually, to the dramatic naturalism of Salvator Rosa, another Neapolitan who excelled in depicting wild landscapes and stormy scenes, though De Marchis's style is generally less rugged. In Rome, he would have been aware of contemporaries like Giovanni Paolo Panini, famous for his vedute (view paintings) of Roman ruins and festivals, and Andrea Locatelli, another landscape specialist whose works often presented a calmer, more Rococo-inflected vision of nature compared to De Marchis's dynamism.

The potential Venetian influences in his handling of color and light might suggest an awareness of artists like Marco Ricci, who worked in both Venice and Rome and was known for his atmospheric landscapes and capricci, often featuring dramatic weather or ruins. Ricci, like De Marchis, played a role in the transition towards the Rococo and later landscape styles. Furthermore, the dramatic intensity and rapid brushwork in some of De Marchis's works resonate, albeit in a different genre, with the flickering energy seen in the paintings of Alessandro Magnasco, active in Genoa and Milan.

Looking forward, the pre-Romantic elements noted in De Marchis's work – the emphasis on atmosphere, emotion, and the power of nature (especially evident in the fire scenes) – anticipate aspects of later landscape painting. While direct influence is hard to trace, his focus on dramatic natural phenomena could be seen as distantly prefiguring the sublime landscapes explored by artists like Francesco Zuccarelli (though often gentler) or even, much later, the elemental concerns of J.M.W. Turner. De Marchis thus occupies a fascinating position, absorbing 17th-century legacies while contributing to the evolving sensibilities of the 18th century.

Critical Reception, Legacy, and Market Value

Throughout his career and afterward, Alessio De Marchis garnered significant attention, both for his artistic skill and his colorful reputation. Art critics and historians acknowledge him as an important figure within the Italian landscape painting tradition of the Settecento (18th century). His technical proficiency, particularly his mastery of light and shadow and his ability to create atmospheric depth, is widely recognized. His works were appreciated for their "bright, viscous, and clear" brushwork, allowing viewers to engage deeply with the depicted scenes.

His historical significance lies partly in his role as a transitional figure. While rooted in the Baroque landscape tradition, his work, with its emphasis on direct observation (however extreme, in the case of the fire studies), atmospheric effects, and emotional resonance, pushed towards new directions. Some scholars identify a "pre-Romantic" sensibility in his art, particularly in the way he could evoke mood and the power of nature, moving beyond purely topographical or idealized representation. He contributed to a shift in landscape aesthetics, emphasizing a more sensitive and sometimes dramatic engagement with the natural world.

Despite the potential controversy surrounding his methods, his paintings were sought after by patrons during his lifetime and have continued to be valued by collectors. Auction records and gallery listings attest to the enduring appeal and market value of his works. Paintings attributed to him, particularly characteristic landscapes or fire scenes, command respectable prices, reflecting his established place in the canon of Italian Old Masters. His legacy is that of a skilled, distinctive, and memorable painter who captured both the tranquility and the turbulence of the world around him, leaving a unique imprint on the history of landscape art.

Conclusion: A Painter of Light and Flame

Alessio De Marchis (1684-1752) remains a compelling figure in Italian art history. Emerging from Naples and forging his career primarily in Rome, Perugia, and Urbino, he distinguished himself as a landscape painter of considerable talent and unique focus. Influenced by masters like Philipp Peter Roos and Gaspard Dughet, he developed a personal style characterized by dynamic brushwork, dramatic use of chiaroscuro, and a remarkable sensitivity to atmospheric effects.

While adept at capturing the peaceful beauty of the Italian countryside, he became particularly famous – even notorious – for his intense and realistic depictions of fire, a theme explored with a passion that allegedly led him to controversial methods of study. His representative works, including pastoral scenes and dramatic conflagrations like the Flight of Aeneas from Troy, showcase his versatility and technical skill. As an artist who bridged Baroque traditions and nascent pre-Romantic sensibilities, De Marchis made a significant contribution to the evolution of landscape painting. His life and work, marked by both artistic dedication and intriguing anecdote, secure his place as a memorable master of light, shadow, and flame in the Italian Settecento.