Andrew Geddes (1783-1844) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of early 19th-century British art. A native of Scotland, he distinguished himself primarily as a portrait painter of considerable sensitivity and skill, and also as a highly accomplished etcher who drew profound inspiration from the Dutch master Rembrandt van Rijn. His career bridged the artistic worlds of Edinburgh and London, and his work reflects both the strong traditions of Scottish portraiture and the broader currents of European art.

Early Life and Reluctant Beginnings

Born in Edinburgh on April 5, 1783, Andrew Geddes was the son of David Geddes, a deputy auditor in the Excise Office. This familial connection to a stable, bureaucratic profession initially set the course for young Andrew's life. He received a classical education at the prestigious Royal High School in Edinburgh, followed by studies at the University of Edinburgh. While his artistic inclinations were present from an early age, his father harbored different ambitions for him, opposing a career in the arts, which was often seen as precarious.

Consequently, upon completing his university education, Geddes entered the Excise Office, the same government department where his father worked. For five years, he dutifully fulfilled his responsibilities, yet the call of art remained strong. The turning point came with his father's death. Freed from paternal opposition and presumably with some inheritance, Geddes, then in his early twenties, made the decisive move to pursue his true passion. He resigned from his post and, in 1807, journeyed to London, the vibrant heart of the British art world, to formally enroll in the esteemed Royal Academy Schools.

Forging an Artistic Path: London and Edinburgh

At the Royal Academy Schools, Geddes immersed himself in the rigorous training offered, which emphasized drawing from casts of classical sculpture and from life models. He quickly began to make his mark. As early as 1806, even before formally enrolling, he had exhibited his first significant work, "St John in the Wilderness," at the Royal Academy's annual exhibition, then held at Somerset House. This debut signaled his ambition to tackle not only portraiture but also historical and religious subjects.

Throughout his career, Geddes maintained a strong connection to his native Scotland, frequently traveling between Edinburgh and London. In Edinburgh, he was part of a lively artistic and intellectual circle. He became a regular exhibitor at the Royal Academy in London and also showed his work at institutions in Scotland. His early years were marked by a dedication to honing his craft, studying the Old Masters, and developing his distinctive style. He shared a studio for a time with his close friend and fellow Scot, David Wilkie, whose genre scenes were already achieving widespread acclaim. This friendship and artistic camaraderie would be a constant throughout their lives.

The Portraitist: Capturing Character and Likeness

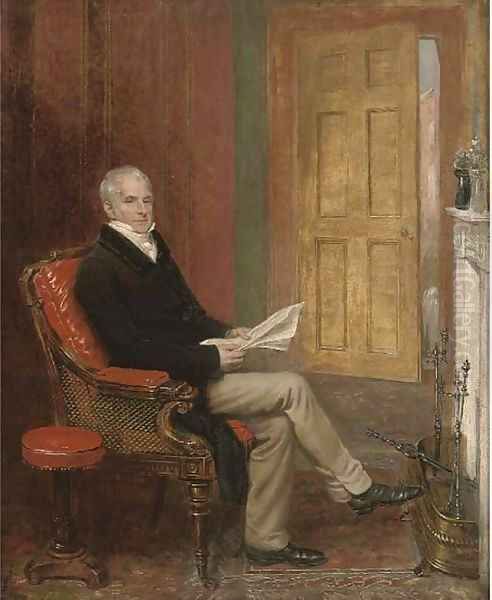

Portraiture formed the bedrock of Andrew Geddes's artistic output and reputation. He possessed a keen ability to capture not just a physical likeness but also the character and inner life of his sitters. His portraits are often distinguished by their warmth, directness, and a certain psychological acuity. He painted many notable figures of his day, demonstrating his growing prominence.

Among his celebrated sitters were fellow artists like Sir David Wilkie, literary figures, and members of Scottish society. His portrait of Dr. Henry Mackenzie, the Scottish novelist and essayist known as "the Man of Feeling," is a fine example of his ability to convey intellectual presence. He also painted Sir Walter Scott, the literary giant of Scotland, a commission that any Scottish artist of the period would have coveted. These works placed him in the lineage of distinguished Scottish portraitists, following in the footsteps of masters like Allan Ramsay and Sir Henry Raeburn, though Geddes developed his own, often more intimate, style.

One of his most tender and renowned portraits is that of his own mother, titled "Summer" or "The Artist's Mother." This work, admired for its gentle realism and affectionate portrayal, is now a prized possession of the National Gallery of Scotland. It showcases his skill in handling paint with a rich, yet controlled, impasto and his sensitivity to the nuances of human expression. Another notable work, "Charles Callender in Turkish Dress," demonstrates his interest in the exotic and his ability to handle rich textures and costumes with flair, a trend popular in Romantic-era portraiture.

A Master Etcher: The Influence of Rembrandt

Beyond his accomplishments in oil painting, Andrew Geddes was a highly gifted and dedicated etcher. In an era when original etching was not as widely practiced or appreciated in Britain as it had been in earlier centuries or would become later in the 19th century, Geddes stood out for his commitment to the medium. He was deeply influenced by the etchings of Rembrandt, admiring the Dutch master's expressive line, dramatic use of chiaroscuro, and ability to convey emotion and atmosphere.

Geddes's etchings encompass portraits, figure studies, and landscapes. His landscape etchings, in particular, show a Rembrandtesque quality, with their evocative play of light and shadow and their often rustic or picturesque subject matter. He produced a series of etchings that were highly regarded by connoisseurs. One of his most famous prints is "The Discovery of the Regalia of Scotland" (1818), which commemorates the rediscovery of the Scottish Crown Jewels in Edinburgh Castle. This subject, rich in national sentiment, was perfectly suited to Geddes's historical interests and his skill as a graphic artist. His etchings are characterized by a confident, often vigorous line and a sophisticated understanding of tonal values. He, along with artists like David Wilkie and later, more extensively, James McNeill Whistler, played a role in the revival of etching as a fine art form.

Historical and Subject Pictures

While portraiture and etching were his primary focus, Geddes also ventured into historical and religious subjects, as evidenced by his early "St John in the Wilderness." In 1831, he completed two significant subject pictures: an "Altar-piece for St James's, Garlickhythe" in London, and "Christ and the Woman of Samaria." These works demonstrate his ambition to engage with the grand tradition of history painting, a genre highly esteemed by the Royal Academy.

Creating an altarpiece was a prestigious commission, and his work for St James's, Garlickhythe (a Wren church in the City of London) would have been a notable achievement. "Christ and the Woman of Samaria" allowed him to explore a narrative biblical scene, requiring skills in composition, figure drawing, and the expression of emotion. While these subject pictures may not have achieved the same consistent acclaim as his portraits or the intimate appeal of his etchings, they underscore the breadth of his artistic interests and his technical versatility. His approach to these subjects often combined a sense of dignity with a human touch, avoiding excessive theatricality.

Travels, Recognition, and Later Years

Geddes's life involved movement not only between Scotland and England but also further afield. He undertook short tours on the European continent, which would have exposed him to a wider range of art, both historical and contemporary. These experiences likely enriched his palette and broadened his artistic perspective, allowing him to see the works of masters like Titian, Veronese, and Rubens firsthand, whose influence can be subtly detected in the richness of some of his paint application.

In 1831, Geddes decided to settle more permanently in London, the center of artistic patronage and exhibition. His talent and perseverance were formally recognized the following year, in 1832, when he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA). This was a significant honor, marking his acceptance into the highest echelons of the British art establishment, alongside contemporaries like J.M.W. Turner, John Constable, and Sir Thomas Lawrence (though Lawrence had died in 1830, his influence was still pervasive).

Despite this professional success, Geddes's health began to decline. He suffered from consumption (tuberculosis), a widespread and often fatal disease in the 19th century. His illness progressively weakened him, and he passed away in London on May 5, 1844, at the age of 61. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Contemporaries

Andrew Geddes's artistic style is characterized by its blend of Scottish realism and a broader European sensibility. In portraiture, he aimed for a truthful representation of his sitters, often imbuing them with a sense of quiet dignity. His brushwork could be fluid and rich, particularly in the rendering of fabrics and flesh tones, sometimes reminiscent of the Venetian school or the work of Sir Joshua Reynolds. However, he generally avoided the overt flattery or grandiosity seen in some contemporary portraitists like Sir Thomas Lawrence, opting for a more direct and often more introspective approach, akin perhaps to the work of his Scottish predecessor, Sir Henry Raeburn, though Geddes's style was often more polished.

The influence of Rembrandt is undeniable, especially in his etchings, but also perceptible in the chiaroscuro and warm tonalities of some of his paintings. He was a knowledgeable collector of Old Master prints, which further informed his own graphic work.

Geddes worked during a vibrant period in British art. Besides his close friend Sir David Wilkie, his contemporaries included the landscape titans J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, whose revolutionary approaches to nature were transforming that genre. In portraiture, Sir Thomas Lawrence was the dominant figure in London for much of Geddes's early career, while in Scotland, Sir Henry Raeburn had set a high standard. Other notable portraitists of the time included Thomas Phillips, John Jackson (who was also a friend of Wilkie and Geddes), George Dawe, and Martin Archer Shee, who succeeded Lawrence as President of the Royal Academy. Geddes also knew artists like Benjamin Robert Haydon, known for his ambitious historical paintings and tumultuous career, and William Etty, celebrated for his nudes and history paintings. The Scottish art scene also featured figures like Alexander Nasmyth, known for landscapes and portraits, and later artists like David Roberts and Clarkson Stanfield who gained fame for their topographical and marine paintings.

Legacy and Collections

Andrew Geddes left behind a significant body of work that continues to be appreciated for its quality and insight. While he may not have achieved the towering fame of some of his contemporaries during his lifetime or immediately after, his reputation has grown steadily, particularly as his etchings have received more scholarly attention. He is recognized as a key figure in the Scottish School of painting and an important contributor to the art of portraiture and etching in Britain.

His works are held in major public collections, most notably the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, which houses important examples of his paintings, including "Summer (The Artist's Mother)" and his portrait of Sir Walter Scott, as well as a comprehensive collection of his etchings. The British Museum in London also has a strong collection of his prints. Other institutions in the UK and abroad hold examples of his work.

His dedication to etching, in particular, helped to keep the tradition of original printmaking alive and paved the way for the etching revival later in the 19th century, which saw artists like Seymour Haden and James McNeill Whistler champion the medium. Geddes's ability to imbue his portraits with personality and his etchings with atmospheric depth ensures his enduring place in the annals of British art.

Conclusion

Andrew Geddes was an artist of considerable talent and integrity. From his initial, reluctant steps into a bureaucratic career to his eventual emergence as a respected painter and etcher, his life was a testament to the power of artistic vocation. He navigated the art worlds of Edinburgh and London with skill, producing portraits that captured the essence of his sitters and etchings that paid homage to the great masters while asserting his own distinct vision. His contribution to Scottish art, and to British art more broadly, lies in the quiet excellence of his work, its psychological depth, and its technical mastery, securing his position as a distinguished artist of the early nineteenth century.