Antoine de Favray (1706-1798) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 18th-century European art. A French painter of considerable talent and ambition, his career unfolded far from the salons of Paris, primarily in the sun-drenched environs of Malta and the exotic allure of Constantinople. Favray's oeuvre, characterized by the elegance of the Rococo, the dignity of the Grand Manner, and a captivating fascination with Orientalist themes, offers a unique window into the cosmopolitan world of the Mediterranean during a period of vibrant cultural exchange. His legacy is not only in his canvases but also in the rich historical narrative they convey about his patrons, their societies, and the artistic currents of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris and Rome

Born on September 8, 1706, in Bagnolet, a commune just outside Paris, Antoine de Favray's early artistic inclinations led him to the traditional path of academic training. While details of his initial studies in Paris are somewhat scarce, it is clear that he absorbed the prevailing artistic tastes of the French capital, which was then a crucible of the burgeoning Rococo style, championed by artists like François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard, though Favray's later work would often lean towards a more formal grandeur.

The pivotal moment in Favray's artistic education came with his journey to Rome. The Eternal City was an essential destination for any aspiring history painter, offering unparalleled access to classical antiquities and Renaissance masterpieces. From 1738, Favray became a student at the prestigious French Academy in Rome, then under the directorship of the accomplished painter Jean-François de Troy (1679-1752). De Troy, known for his large-scale historical and mythological compositions, as well as his elegant tapestry designs like the Story of Esther, exerted a profound influence on Favray. Under his tutelage, Favray honed his skills in draughtsmanship, composition, and the handling of complex figural groups, all essential components of the "Grand Manner" of painting.

During his Roman sojourn, Favray would have been exposed to a vibrant international artistic community. He likely encountered the work of prominent Italian painters such as Pompeo Batoni, a leading figure in Roman portraiture and history painting, and Marco Benefial, who, like de Troy, maintained a significant workshop. The influence of earlier masters, such as Carle van Loo, who had also served as director of the French Academy in Rome and was a versatile proponent of both Rococo charm and grand historical painting, would have been part of the academic discourse. Favray's time in Rome, which lasted until 1744, provided him with a solid foundation in the classical tradition, tempered by the prevailing French elegance, a combination that would define his subsequent career. He also formed connections that would prove crucial, including with members of the Knights of St. John.

The Maltese Period: A Knight-Painter in the Service of the Order

In 1744, at the invitation of several Knights of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem (also known as the Knights of Malta), Antoine de Favray relocated to Malta. This move marked the beginning of the most significant and productive phase of his career. The island, a strategic bastion in the Mediterranean, was ruled by the Order, a wealthy and influential religious and military organization with a pan-European membership. This elite society provided a fertile ground for artistic patronage.

Favray quickly established himself as a favored painter among the Knights and the Maltese nobility. His skill in portraiture, combined with his ability to convey status and authority, was highly sought after. In 1751, a testament to his standing and integration within this society, Favray himself was received into the Order of St. John as a Knight of Grace. This honor not only conferred prestige but also further solidified his position within the island's intricate social and political fabric. He would spend the majority of his working life in Malta, with an important interlude in Constantinople.

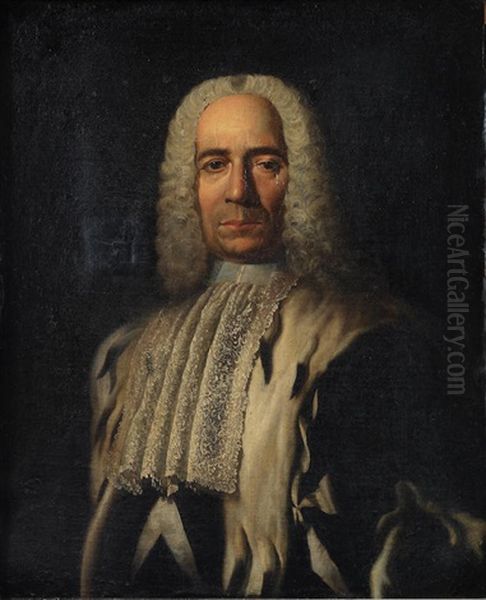

Portraits of Distinction: Capturing the Maltese Elite

Favray's portraiture from his Maltese period is perhaps his most celebrated contribution. He excelled in the "Grand Manner" portrait, a style that aimed to ennoble the sitter by depicting them with idealized features, elegant poses, and symbolic accoutrements set against impressive backdrops. His subjects included Grand Masters of the Order, high-ranking knights, church dignitaries, and members of prominent Maltese families.

Among his most iconic works is the Portrait of Grand Master Emmanuel Pinto da Fonseca (painted multiple times, with a notable version around 1747). Pinto, who reigned from 1741 to 1773, was known for his regal bearing and ambitious projects. Favray depicted him with all the trappings of power and sovereignty: clad in armor and ermine-lined robes, often gesturing authoritatively, surrounded by symbols of his office and the Order's might. These portraits are not mere likenesses; they are carefully constructed statements of authority, rendered with meticulous attention to the textures of fabrics, the gleam of metal, and the dignified comportment of the sitter. The influence of portraitists like Hyacinthe Rigaud, who famously painted Louis XIV, can be discerned in the majestic staging of these works.

Favray also painted numerous portraits of other knights and Maltese ladies. His depictions of women, often adorned in the traditional Maltese għonnella (a distinctive hooded cloak) or elaborate European fashions, showcase his sensitivity to costume and character. These works provide invaluable visual records of Maltese society and fashion in the 18th century. He developed close ties with certain families, such as the Lott family, for whom he executed several commissions.

Religious Commissions and Narrative Paintings

Beyond portraiture, Favray was also active as a painter of religious and historical subjects, primarily for the churches and chapels of the Order. His training in Rome under de Troy had equipped him well for large-scale narrative compositions. His most significant religious works in Malta were created for St. John's Co-Cathedral in Valletta, the conventual church of the Order.

For this magnificent Baroque edifice, already richly decorated by artists like Mattia Preti in the previous century, Favray contributed several important pieces. These included three large lunette paintings depicting scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist, the patron saint of the Order. These works, such as The Beheading of St. John the Baptist, demonstrate his ability to handle dramatic narratives, complex figural arrangements, and expressive emotion, all within the grandiloquent style favored by his patrons. He also painted altarpieces and other devotional images for various chapels and auberges (the traditional lodges of the Knights).

His religious paintings, while adhering to traditional iconography, often display a Rococo lightness in their palette and a certain theatricality in their staging, distinguishing them from the more somber drama of earlier Baroque masters. There is evidence of some friction during this period, notably a disagreement with the Portuguese architect and painter Niccolò Nasoni, who was also active in Malta, regarding decorations for St. John's, though Favray's reputation largely endured. He also collaborated with, or worked alongside, local Maltese artists such as Francesco Zahra (1710-1773) and Gio Nicola Buhagiar (1698-1752), who were significant figures in the development of Maltese Baroque and Rococo art.

Depictions of Maltese Life and Early Orientalist Leanings

Favray's keen observational skills extended beyond formal portraiture and religious scenes. He produced a number of genre paintings and studies depicting Maltese customs, costumes, and daily life. These works, often characterized by a charming ethnographic interest, foreshadow his later engagement with Orientalist themes. His paintings of Maltese women in traditional attire are particularly noteworthy, capturing the unique cultural identity of the island.

These depictions often blend a documentary impulse with an aesthetic sensibility that found the "exotic" appealing. This interest in the "other" was a growing trend in European art and culture, and Favray's location in Malta, a crossroads of Mediterranean cultures, provided ample subject matter. His meticulous rendering of textiles and local details in these works demonstrates a fascination that would fully blossom during his time in the Ottoman Empire.

The Constantinople Interlude: An Ambassador's Painter

In 1762, Favray embarked on a new chapter in his career, traveling to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), the capital of the Ottoman Empire. He remained there for nearly a decade, until 1771. This period was immensely significant, allowing him to immerse himself in a culture that held a powerful allure for many Europeans. His primary role in Constantinople was as a painter to the French ambassador, Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, a prominent diplomat who would later become French Foreign Minister.

Favray produced a series of remarkable portraits of the Comte de Vergennes and his wife, Anne Duvivier, often depicted in lavish Turkish attire – a popular genre known as "turquerie." These portraits, such as Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, in Turkish Costume and Madame de Vergennes in Turkish Costume, are masterpieces of Orientalist painting. They combine the formal elegance of French portraiture with an exquisitely detailed rendering of Ottoman fabrics, furnishings, and cultural objects. Favray's meticulous attention to the rich silks, embroidered kaftans, and intricate patterns of Turkish carpets is astonishing.

These works were not simply costume pieces; they were also reflections of diplomatic identity and the European fascination with the Ottoman world. They catered to a taste for the exotic while maintaining the dignity and status of the sitters. During his time in Constantinople, Favray would have been aware of, or perhaps even encountered, other European artists interested in similar themes, such as the Swiss painter Jean-Étienne Liotard, who had also spent time in the Levant and was renowned for his pastel portraits and scenes of Turkish life. The legacy of earlier artists like Jean-Baptiste Vanmour, who had documented Ottoman court life for European patrons, also formed part of the visual culture surrounding Orientalism.

Beyond portraits, Favray also painted panoramic views of Constantinople, capturing the city's stunning skyline of mosques and minarets, its bustling waterways, and its vibrant street life. Works like his Panorama of Constantinople offer a sweeping vista of the city, demonstrating his skill in landscape and topographical painting. These paintings provided Europeans with vivid, if somewhat romanticized, glimpses into a world that was both admired and perceived as fundamentally different. His detailed depictions of public audiences, processions, and everyday scenes further enriched the European visual understanding of the Ottoman capital.

Return to Malta and Later Years

After his productive sojourn in Constantinople, Favray returned to Malta in 1771. He resumed his position as a leading painter on the island, continuing to receive commissions for portraits and religious works. His experiences in the East had undoubtedly enriched his artistic vision, and elements of Orientalist detail and a heightened sensitivity to color and texture can be seen in his later Maltese works.

He continued to paint portraits of prominent figures, including later Grand Masters and knights. His style, while still rooted in the Grand Manner, may have incorporated a more intimate or nuanced approach to characterization, possibly influenced by the diverse human subjects he encountered in Constantinople. He remained active well into his old age, a respected figure in Maltese artistic and social circles.

Antoine de Favray died in Malta on February 9, 1798, at the venerable age of 91. His death occurred just months before the Order of St. John was expelled from Malta by Napoleon Bonaparte's forces, an event that marked the end of an era for the island and its unique cultural milieu, which Favray had so diligently chronicled.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Influences

Antoine de Favray's artistic style is a complex amalgamation of several contemporary European trends, adapted to his unique career path and personal inclinations.

Grand Manner: At its core, much of Favray's portraiture and historical painting adheres to the principles of the Grand Manner. This involved idealizing subjects, employing noble poses and gestures, incorporating classical allusions, and creating a sense of dignity and importance. His Roman training under de Troy was crucial in instilling these academic ideals. This approach aligned well with the self-image of his patrons, particularly the Knights of St. John.

Rococo Elegance: Despite the formality of the Grand Manner, Favray's work, especially in its handling of fabrics, color, and a certain lightness of touch, shows the influence of the French Rococo. His palette could be rich and vibrant, and there is often an undeniable decorative quality to his compositions, particularly in the intricate rendering of costumes and accessories. This Rococo sensibility is evident in the graceful lines and refined atmosphere of many of his portraits. Artists like Jean-Marc Nattier, known for his elegant portraits of French court ladies, represent a parallel development in French Rococo portraiture.

Orientalism: Favray is a key figure in 18th-century Orientalist painting. His time in Constantinople provided him with firsthand experience of Ottoman culture, which he translated into works of remarkable detail and ethnographic interest. Unlike some Orientalist painters who relied on fantasy, Favray's depictions, while still filtered through a European lens, often possess a high degree of accuracy in their rendering of costumes, textiles, and settings. His meticulous technique was well-suited to capturing the opulent surfaces and intricate patterns of Eastern art and design.

Realism and Detail: A hallmark of Favray's style is his painstaking attention to detail. Whether depicting the lace on a cuff, the embroidery on a kaftan, the reflection on armor, or the specific features of a cityscape, Favray's brushwork is often precise and highly finished. This meticulousness, while sometimes criticized by contemporaries who perhaps favored a broader, more painterly approach (like, for instance, the emerging Neoclassical sobriety of Anton Raphael Mengs or the atmospheric effects of Thomas Gainsborough in England), lends his work a tangible reality and historical value.

Composition and Color: Favray was a skilled composer, capable of managing complex multi-figure scenes in his narrative paintings and creating balanced and imposing arrangements in his portraits. His color palette was versatile, ranging from the somber and dignified tones appropriate for official portraiture to the brighter, more exotic hues of his Orientalist works.

His influences were diverse, stemming from his French academic background (de Troy, van Loo), his Roman experience (Batoni, Benefial, classical and Renaissance art), and his direct observations in Malta and Constantinople. He, in turn, influenced the course of art in Malta, contributing to the development of a sophisticated local school that blended Italianate Baroque traditions with French Rococo elegance.

Legacy and Critical Reception

Antoine de Favray's legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he produced a substantial body of work characterized by technical skill, elegance, and a keen eye for detail. His portraits remain important documents of the European elite in the Mediterranean, particularly the Knights of St. John and the French diplomatic corps in the Ottoman Empire. His religious paintings contributed significantly to the artistic patrimony of Malta.

Critically, Favray was highly regarded in his time, especially by his patrons. His ability to satisfy their desire for representation that conveyed both status and a contemporary aesthetic sensibility ensured his success. In the broader history of art, he is particularly noted for his contributions to Orientalist painting, providing some of the most compelling and detailed European depictions of Ottoman life in the mid-18th century.

His work provides invaluable historical documentation. Through his eyes, we gain insight into the ceremonial life of the Knights of Malta, the fashions and customs of Maltese society, and the appearance of Constantinople and its inhabitants during a fascinating period of cultural interaction. His paintings are frequently consulted by historians of costume, diplomacy, and Mediterranean social life.

While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his Parisian contemporaries like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, whose quiet domestic scenes offered a different path, Favray excelled within his chosen domain. He successfully navigated the demands of patronage across different cultural contexts, adapting his French academic training to the specific environments of Malta and the Ottoman Empire. His dedication to meticulous representation, even if occasionally leading to criticism for excessive detail, has ultimately enhanced the historical and artistic value of his work.

Today, Antoine de Favray's paintings are held in major museums and private collections worldwide, including the Louvre in Paris, the National Museum of Fine Arts in Valletta, Malta, and the Pera Museum in Istanbul. Exhibitions of his work continue to draw attention to his unique career and his contribution to 18th-century European art, reaffirming his status as a master painter who bridged cultures and chronicled a vibrant, interconnected Mediterranean world. His art remains a testament to a life spent capturing the light, color, and character of a world far from his native France, yet indelibly marked by his sophisticated French artistry.