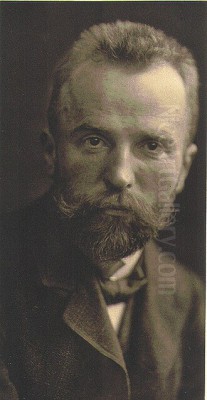

Arthur Illies (1870-1952) stands as a significant yet complex figure in the landscape of German art during the late 19th and first half of the 20th centuries. A painter, printmaker, and influential teacher, Illies made substantial contributions to the artistic development of Hamburg, his native city. He was celebrated by some as a "nurturer of a generation of Impressionists" and a "revolutionary" force. However, his career unfolded during tumultuous times, including World War I and the rise of National Socialism, and his association with conservative and nationalist ideologies, including membership in the Nazi Party (NSDAP), casts a long shadow over his artistic legacy, prompting ongoing debate and re-evaluation.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Hamburg on February 9, 1870, Arthur Illies was the son of a merchant, Theodor Friedrich Wilhelm Illies, and his wife Emilie, née FOCK. This Hanseatic upbringing in a bustling port city would later deeply inform his subject matter. His formal artistic training began with painting lessons from 1886 to 1889. Seeking to broaden his horizons, Illies moved to Munich, a major artistic center at the time. There, he attended the School of Arts and Crafts (Kunstgewerbeschule) and subsequently enrolled at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts. His time in Munich exposed him to the prevailing currents of late Naturalism and the emerging Symbolist and Jugendstil movements, which were gaining traction against the established academic traditions.

A pivotal moment in his early career occurred in 1891 when Alfred Lichtwark, the visionary director of the Hamburger Kunsthalle, recognized Illies's potential. Lichtwark, a key proponent of modern art in Germany and a champion of local Hamburg talent, invited Illies to Hanover. This connection with Lichtwark was significant, as Lichtwark was instrumental in promoting French Impressionism in Germany and encouraging German artists to develop their own modern vernacular. Illies also studied at the private Valeska Röver Art School in Hamburg, where he learned alongside contemporaries such as Ernst Eitner, who would also become a notable Hamburg artist.

Emergence in the Hamburg Art Scene and Stylistic Development

Returning to Hamburg, Illies quickly established himself as a prominent figure. He became a member of the Hamburg Artists' Club (Hamburger Künstlerclub von 1897), a group founded by Lichtwark that aimed to foster a modern artistic identity for the city. This club included artists like Ernst Eitner, Thomas Herbst, and Arthur Siebelist, with whom Illies maintained friendly relations. He was also a significant member of the Hamburgische Künstlervereinigung (Hamburg Artists' Association). His involvement in these circles placed him at the forefront of Hamburg's avant-garde.

Illies's artistic style evolved, embracing elements of Impressionism, particularly in his landscape paintings which often depicted the Lüneburg Heath or the environs of Hamburg. He was adept at capturing atmospheric effects and the play of light. However, he is perhaps best known for his contributions to Jugendstil (the German iteration of Art Nouveau), especially in his graphic works. His etchings and lithographs often featured stylized natural forms, decorative patterns, and a distinctive sense of line and composition. He explored themes ranging from Hamburg's street scenes and bustling harbor to animal studies, nudes, and even fairy-tale subjects. His pioneering graphic works were considered avant-garde and highly influential.

Master of Modern Etching and Representative Works

Arthur Illies was particularly renowned for his modern etchings, which were characterized by rich coloration, often imbued with a sense of mystery, and a sophisticated fusion of intricate decorative design with a unique personal approach to color. His mastery in this medium allowed him to explore textures and moods with remarkable subtlety and power.

One of his most celebrated works is the color etching Mondsichel über einem Ährenfeld (Crescent Moon over a Cornfield). This piece exemplifies his skill in combining detailed, almost ornamental depictions of nature – the meticulously rendered ears of corn – with an evocative, atmospheric use of color to create a scene that is both naturalistic and poetically charged. The interplay of light and shadow, and the symbolic resonance of the crescent moon, contribute to the work's modern sensibility and its departure from purely academic representation.

Another significant example of his printmaking prowess is Drei Tulpen (Three Tulips), a color zinc etching. In this work, Illies employs strong, clear lines to delineate the flowers, setting them against a dark background that makes their forms and colors stand out dramatically. The composition is deceptively simple yet demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of form, color harmony, and the expressive potential of the etching medium. These works, among others, solidified his reputation as an innovator in graphic arts.

Teaching and Influence on a Generation

Beyond his own artistic production, Arthur Illies made a lasting impact as an educator. He taught at the Hamburg School of Applied Arts (Staatliche Kunstgewerbeschule Hamburg), where he was regarded as a significant mentor. He is credited with having "nurtured an entire generation of Impressionists," guiding his students while encouraging them to find their own artistic voices. His teaching philosophy likely emphasized direct observation, a modern approach to color and light, and technical proficiency, particularly in printmaking.

One of his notable students was Hertha Spier, who went on to become a respected portrait painter. The influence of a dedicated teacher like Illies can be seen not only in the direct stylistic lineage of his students but also in the broader invigoration of the Hamburg art scene. His role as an educator contributed to his reputation as a "revolutionary" figure who helped pave the way for new artistic directions in the city.

Interactions with Contemporaries

Arthur Illies was an active participant in the German art world, and his career intersected with many prominent artists of his time. As a member of the Hamburger Künstlerclub, he was in regular contact with fellow Hamburg artists like Ernst Eitner, Thomas Herbst, and Arthur Siebelist. He also shared a friendly relationship with Otto Modersohn, one of the founders of the Worpswede artists' colony, a significant hub for landscape painting and early modernism in Germany. Other artists associated with Worpswede included Fritz Mackensen, Hans am Ende, Heinrich Vogeler, and Paula Modersohn-Becker, whose work, like Illies's, often focused on the local landscape and rural life, albeit with differing stylistic emphases.

Illies's work was frequently exhibited alongside that of leading German Impressionists such as Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt. These artists were central to the Berlin Secession and represented the vanguard of modern art in Germany at the turn of the century. Being exhibited with them indicates Illies's recognition within these progressive circles and his alignment with modern artistic tendencies. His connection to Alfred Lichtwark, the influential director of the Hamburger Kunsthalle, further underscores his integration into the network of artists and patrons driving artistic innovation. Lichtwark also championed artists like Friedrich Ahlers-Hestermann and, for a time, the tragically fated Anita Rée, both associated with the Hamburg Secession.

His personal life also brought him into contact with other artistic families. He married Jutta Bossard (née Lamprecht, daughter of the aforementioned Alfred Lamprecht, though some sources state her maiden name was Krull and she was the widow of Dr. Krull before marrying Bossard, and then Illies after Bossard's death – the provided text states "Jutta Bossard" as his wife, implying she was perhaps widowed or divorced from Johann Michael Bossard). The provided information indicates he connected with the Bossard family through his friend, the artist Georg Slaytermann von Langeweyde. Johann Michael Bossard was himself a significant, if idiosyncratic, artist known for the Gesamtkunstwerk "Kunststätte Bossard."

The Shadow of National Socialism

The rise of the Nazi Party to power in 1933 marked a dark turn for Germany and its cultural life. Arthur Illies, described as a supporter of conservative and nationalist ideologies, became a member of the NSDAP. He also joined the National Socialist People's Welfare (Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt) and the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts (Reichskammer der bildenden Künste). Membership in the latter was virtually mandatory for artists wishing to continue working and exhibiting professionally during the Third Reich.

His political affiliations during this period are a contentious aspect of his biography. While some artists were persecuted, their work declared "degenerate" (entartete Kunst) – figures like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde (despite his own Nazi sympathies), or the aforementioned Anita Rée (who took her own life in 1933 partly due to persecution) – others, particularly those whose work aligned with or was tolerated by the regime's vague aesthetic ideals of "German art," were able to continue their careers. Illies's art, with its focus on landscape, traditional themes, and a style that was not radically abstract or expressionistic, likely found acceptance.

His friend, Georg Slaytermann von Langeweyde, was also a Nazi and exhibited works at the "Great German Art Exhibition" (Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung) in Munich, the regime's official showcase for approved art. This connection further situates Illies within a network of artists who were, at the very least, compliant with or supportive of the Nazi regime. The extent to which Illies actively promoted Nazi ideology through his art or actions, or whether his membership was a matter of opportunism or deeply held conviction, remains a subject of historical inquiry.

Post-War Repercussions and Attempts at Rehabilitation

After the collapse of the Third Reich in 1945, Germany underwent a period of denazification. Individuals who had been members of the Nazi Party or associated organizations faced scrutiny. In 1946, Arthur Illies's pension was cancelled, and his bank account was frozen, reportedly due to health reasons cited by the authorities, though this was likely a euphemism or a consequence related to his Nazi-era affiliations. He appealed this decision, claiming he had been treated unjustly, but his appeal was not successful.

Despite these difficulties, he reportedly maintained good relations with figures like Johann Michael Bossard and continued his artistic activities. In the aftermath of the war and the revelations of Nazi atrocities, many individuals sought to downplay or reframe their roles during the regime. Arthur Illies's son, Kurt Illies, later took on the task of managing his father's legacy. He published memoirs and letters of his father, an effort interpreted by some as an attempt to rehabilitate Arthur Illies's image and perhaps mitigate the criticisms related to his conduct and affiliations during the Nazi era. This effort highlights the complex and often painful process of confronting and understanding the past for families of those involved with the regime.

Artistic Honors and Enduring Legacy

Despite the controversies, Arthur Illies's contributions to art, particularly in Hamburg, received recognition during his lifetime and posthumously. In 1951, the Hamburg Museum (Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte) organized an exhibition celebrating his artistic career, a significant honor. On this occasion, he was also made an honorary member of the Hamburg Artists' Association, a testament to the esteem in which he was held by his peers for his artistic achievements.

The provided information mentions that Arthur Illies (or more likely, his work and legacy) received the European Spirit Gold Medal for German Cultural Works in 1970 and that he was granted honorary citizenship of Hamburg in 1973. Given that Illies passed away in 1952, these honors would have been posthumous, likely awarded to his oeuvre or in recognition of his foundational impact on Hamburg's art, perhaps through the activities of the foundation established in his name.

To preserve and promote his work, the Illies and Georgies Family Foundation (Illies und Georgies Familienstiftung) was established in Lüneburg. This foundation continues to hold and care for Arthur Illies's artistic estate, ensuring that his paintings and prints are available for study and exhibition. His works continue to be featured in exhibitions, and his etchings, in particular, are frequently cited in art historical literature on German printmaking and Jugendstil.

Unresolved Questions and Ongoing Assessment

Arthur Illies remains a figure of artistic importance whose legacy is irrevocably complicated by his political choices during a dark chapter of German history. The primary artistic controversy surrounding him revolves around his role and activities during the Nazi era. Was his art co-opted by the regime? Did his conservative nationalism translate into active support for Nazi cultural policies? How did his membership in the NSDAP influence his artistic opportunities and output, and the perception of his work by his contemporaries and by later generations?

The fact that he was penalized after the war suggests that Allied or German authorities found his involvement significant enough to warrant sanctions. Yet, his continued artistic activity and the efforts to preserve his legacy indicate a persistent belief in the value of his art, separate from, or in complex dialogue with, his political biography. The "unresolved mystery" lies in fully understanding the interplay between his artistic convictions, his personal ideology, and the pressures and opportunities of his time. His relationship with figures like Slaytermann von Langeweyde, who was more overtly aligned with Nazi art, versus his earlier associations with progressive artists, paints a picture of a career that navigated shifting and treacherous terrains.

Conclusion: An Artist of His Time

Arthur Illies's life and work offer a compelling case study of an artist deeply embedded in the artistic and social currents of his time. From his early embrace of Impressionist principles and his significant contributions to Jugendstil graphics to his influential role as a teacher in Hamburg, his impact on the regional art scene is undeniable. He was a bridge figure, connecting the late 19th-century innovations with the modern art movements of the early 20th century.

However, his biography is also a reminder of the complex moral and political challenges faced by individuals during periods of profound societal upheaval. His association with National Socialism complicates any straightforward celebration of his artistic achievements, demanding a nuanced and critical perspective. Arthur Illies's legacy, therefore, is not monolithic; it is a tapestry woven with threads of artistic brilliance, pedagogical influence, and the somber hues of a problematic political past. His work continues to be appreciated for its aesthetic qualities and historical significance, while his life story serves as a pertinent reminder of the often-uncomfortable intersections of art, artists, and ideology.