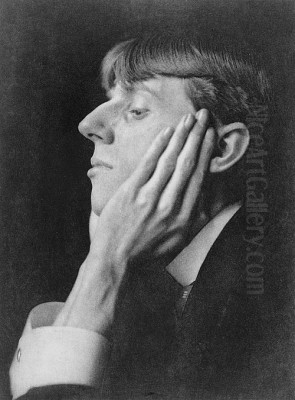

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley remains one of the most striking and controversial figures in the history of British art. Emerging during the vibrant, often contradictory, final decades of the Victorian era, his unique artistic vision, executed primarily in black ink, shocked and captivated audiences. Though his career spanned a mere six years before his tragically early death, Beardsley's influence permeated the Art Nouveau movement and continues to resonate in graphic design and illustration today. He was a central figure in the Aesthetic and Decadent movements, a master of line whose work explored themes of the grotesque, the erotic, and the artificial with unparalleled elegance and audacity.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley was born in Brighton, England, on August 21, 1872. His family background was somewhat precarious; his father, Vincent Paul Beardsley, was a man of uncertain means, while his mother, Ellen Agnus Pitt, came from a family with a more substantial inheritance. This financial instability marked Beardsley's early years. More significantly, his childhood was overshadowed by illness. At the age of seven (some sources say nine), he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, the lung disease that would ultimately claim his life and cast a long shadow over his existence.

Despite his frail health, Beardsley displayed prodigious talent from a young age, not only in drawing but also in music. He was considered a musical prodigy by some. His formal education took place at Brighton Grammar School and later Bristol Grammar School, where his artistic inclinations began to flourish more publicly. He produced drawings and caricatures for school publications, offering early glimpses of his sharp wit and developing graphic style.

After leaving school, Beardsley moved to London in 1888 and took up a mundane position as a clerk in an insurance office – a stark contrast to his artistic aspirations. However, London offered exposure to a burgeoning art scene. A pivotal moment occurred in 1891 when, encouraged by his family, he visited the studio of the renowned Pre-Raphaelite painter Sir Edward Burne-Jones. Showing Burne-Jones his portfolio, the young Beardsley received crucial validation. Burne-Jones, impressed by the originality and power of the drawings, urged him to pursue art seriously. Around the same time, Beardsley briefly attended classes at the Westminster School of Art under Professor Fred Brown, though his unique style was largely self-taught and developed independently.

The Influence of Japonisme and the Pre-Raphaelites

Beardsley's artistic development occurred at a time when various influences were converging in London's art world. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, though its initial phase was decades earlier, still exerted influence through figures like Burne-Jones and William Morris. Beardsley admired their attention to detail, medieval themes, and decorative qualities. He was particularly drawn to the intricate patterns and romanticism found in Burne-Jones's work.

However, perhaps the most profound influence on Beardsley's emerging style was Japonisme – the European fascination with Japanese art, particularly Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, which had swept across the continent in the latter half of the 19th century. Artists like James McNeill Whistler, an American expatriate living in London whom Beardsley admired (and later had a complex relationship with), had already incorporated Japanese principles into their work. Beardsley absorbed elements such as the flattened perspective, asymmetrical compositions, the emphasis on bold outlines, large areas of flat black or white, and the decorative use of pattern. He adapted these techniques to his own ends, creating a style that was both indebted to Japanese aesthetics and uniquely his own.

The Rise to Fame: Le Morte d'Arthur

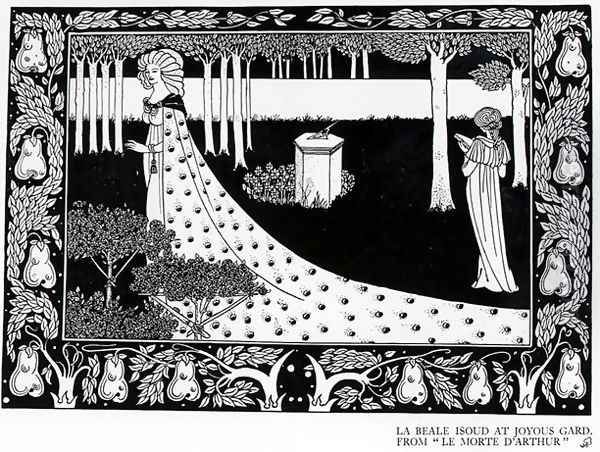

Following Burne-Jones's encouragement, Beardsley began to dedicate himself more fully to art. His breakthrough commission came in 1892 from the publisher J.M. Dent. Inspired by the success of William Morris's Kelmscott Press and its revival of high-quality book printing, Dent commissioned Beardsley to illustrate a new edition of Sir Thomas Malory's epic Arthurian legend, Le Morte d'Arthur. This was a monumental undertaking for the young artist, requiring over 350 illustrations, chapter headings, borders, and initials.

The Morte d'Arthur illustrations, produced between 1893 and 1894, showcase Beardsley's early style, blending the influence of Burne-Jones's medievalism with the bold linearity and decorative patterns derived from Japanese prints. While some drawings retain a certain Pre-Raphaelite sensibility, others demonstrate a growing confidence in his distinctive use of line and stark black-and-white contrasts. The work established Beardsley's reputation as a major new talent in illustration, though he himself grew somewhat weary of the project's demands and the perceived constraints of its style.

Salome and the Cult of Decadence

Beardsley's association with the writer Oscar Wilde cemented his position at the heart of the Aesthetic and Decadent movements in London. Aestheticism, with its mantra of "art for art's sake," championed beauty and artistic refinement above moral or didactic concerns, often drawing inspiration from classical and Renaissance art, as well as Japanese aesthetics. Decadence, a related but more provocative offshoot, embraced themes of artificiality, perversity, ennui, and the taboo, often challenging the strict moral codes of Victorian society.

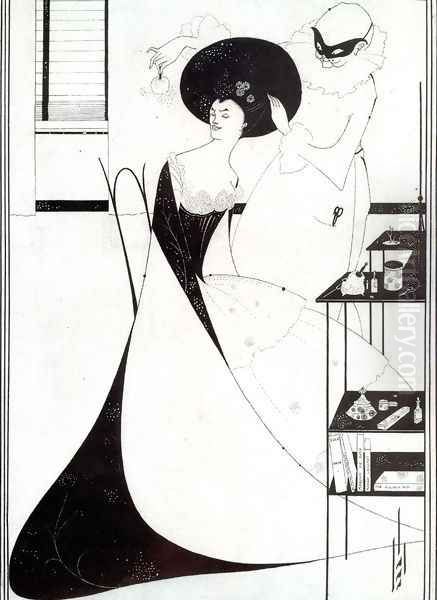

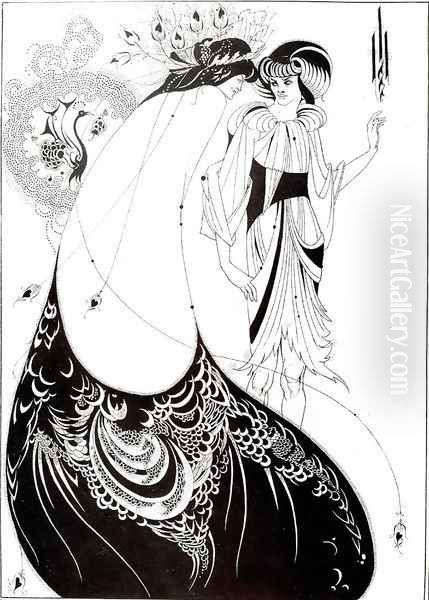

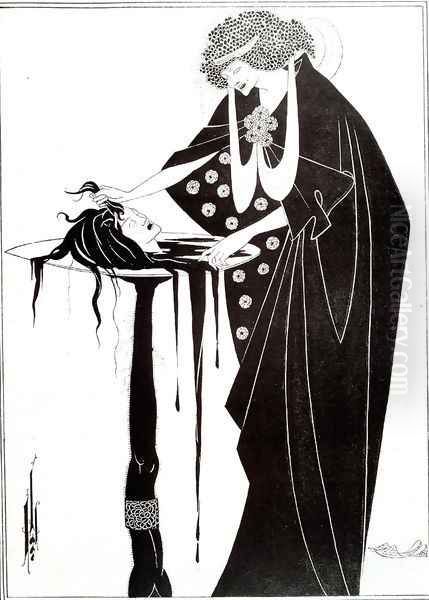

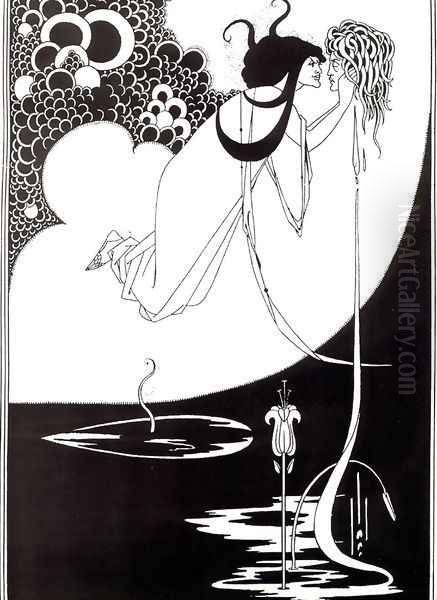

In 1893, Beardsley was commissioned to illustrate the English edition of Wilde's controversial one-act play, Salome. Originally written in French, the play retold the biblical story of Salome, Herodias's daughter, who demands the head of John the Baptist on a platter as a reward for her dance. Wilde's version was infused with sensuality, obsession, and necrophilia, making it a perfect vehicle for Beardsley's burgeoning decadent style.

Beardsley produced a series of astonishing illustrations for Salome that became instantly infamous. Works like "The Woman in the Moon," "The Peacock Skirt," "The Dancer's Reward," and particularly "The Climax" (depicting Salome kissing the severed head of John the Baptist) were unlike anything seen before in mainstream British publishing. They combined exquisite decorative detail with grotesque imagery and overt eroticism. Figures were elongated and stylized, set against stark, patterned backgrounds. Beardsley subtly altered some details between the initial drawings and the published versions, sometimes toning down overtly explicit elements or adding sly caricatures, including one possibly mocking Wilde himself. The Salome illustrations perfectly captured the play's perfumed, claustrophobic atmosphere and became iconic images of the Decadent movement. They also solidified Beardsley's reputation as an enfant terrible of the art world.

The Master of Line: Analyzing Beardsley's Style

Beardsley's genius lay in his extraordinary command of line. He worked almost exclusively in black ink on white paper, creating images of startling clarity and impact. His line could be incredibly fine and delicate, weaving intricate patterns reminiscent of lace or embroidery, or bold and assertive, defining forms with sharp, decisive contours. He masterfully exploited the tension between solid black areas and stark white space, using these contrasts to create dramatic effects, define form, and guide the viewer's eye.

His style was characterized by:

Linearity: An absolute focus on the quality and expressive potential of the line itself.

Flatness: Often rejecting traditional perspective and shading in favor of flat planes of black and white, influenced by Japanese prints.

Decorative Pattern: Intricate and imaginative use of patterns in clothing, backgrounds, and hair, often overwhelming the figures themselves.

Stylization and Artificiality: Figures are often elongated, distorted, or puppet-like, emphasizing artifice over naturalism. Gender is frequently ambiguous.

Grotesque and Erotic Elements: A fascination with the bizarre, the monstrous, and the sexually suggestive, often presented with elegant detachment.

Economy: Despite the complexity of some designs, Beardsley could also achieve powerful effects with remarkable simplicity and economy of line.

He was dubbed the "King of Line," a title reflecting his unparalleled draftsmanship and the centrality of line in his artistic vision. His work demonstrated how black-and-white illustration could be as powerful and expressive as painting. Other artists known for their distinctive line work, such as the German Renaissance master Albrecht Dürer or later graphic artists like Heinrich Kley, offer points of comparison, but Beardsley's synthesis of influences and his particular thematic concerns resulted in a style that remains utterly unique.

The Yellow Book and Public Scandal

In 1894, Beardsley reached the height of his fame and notoriety as a co-founder and the first art editor of The Yellow Book. Published by John Lane at The Bodley Head, this avant-garde quarterly magazine aimed to showcase the best of modern art and literature, separating the two entirely within its pages. Beardsley designed the striking yellow covers and contributed numerous illustrations, alongside literary contributions from writers like Henry James, Max Beerbohm (who was also a gifted caricaturist and friend of Beardsley), and W.B. Yeats.

The Yellow Book quickly became synonymous with the Aesthetic and Decadent movements, its provocative content and Beardsley's daring illustrations attracting both admiration and outrage. It represented a challenge to the conservative establishment of Victorian England. Beardsley's contributions continued to push boundaries, featuring androgynous figures, satirical portrayals of society, and coded references to forbidden desires.

However, Beardsley's association with The Yellow Book came to an abrupt end due to his connection with Oscar Wilde. In April 1895, Wilde was arrested on charges of "gross indecency" following his disastrous libel suit against the Marquess of Queensberry. When arrested, Wilde was reportedly carrying a yellow book (though likely a French novel, not The Yellow Book itself). The press and public, already suspicious of the magazine's decadent tone, conflated Beardsley and The Yellow Book with Wilde's scandal. Facing immense pressure and outrage from conservative authors and the public, publisher John Lane dismissed Beardsley from his position as art editor. This event was a significant blow to Beardsley, both professionally and personally, despite his having no direct involvement in Wilde's legal troubles.

The Savoy and Later Works

Dismissed from The Yellow Book, Beardsley soon found a new, perhaps even more suitable, outlet for his work. He teamed up with the poet Arthur Symons and the unconventional publisher Leonard Smithers to launch The Savoy in 1896. Smithers was known for publishing risqué and avant-garde literature, including works considered pornographic by mainstream society. The Savoy was intended to be even more daring than The Yellow Book, and Beardsley served as its principal artist.

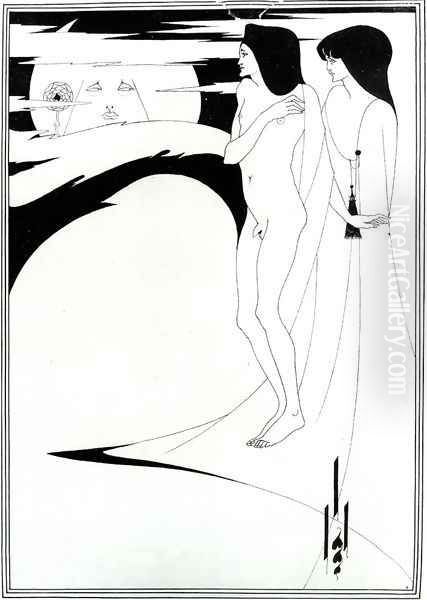

His work for The Savoy shows a further evolution in his style, perhaps even darker and more cynical after the Wilde scandal fallout. He contributed illustrations, cover designs, and even literary pieces, including excerpts from his unfinished erotic novel Under the Hill (a retelling of the Tannhäuser legend).

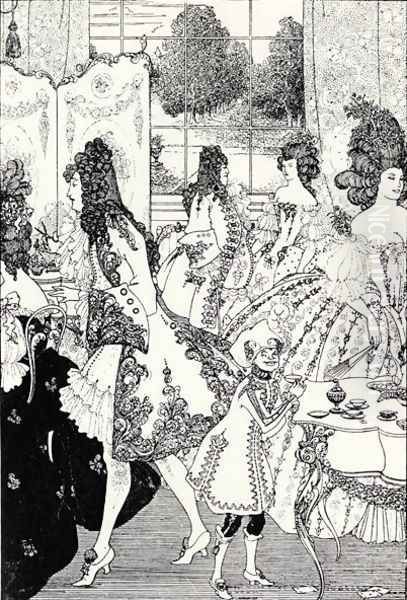

During this later period, Beardsley also undertook other significant commissions. He produced illustrations for Alexander Pope's satirical poem The Rape of the Lock, creating images of exquisite, rococo-inspired delicacy that perfectly matched the poem's artificiality. Perhaps his most controversial work from this time was a series of illustrations for a privately printed edition of Aristophanes's classical comedy Lysistrata. These drawings were overtly phallic and sexually explicit, far exceeding the suggestiveness of his earlier work, and remain some of his most shocking images. He also created illustrations for works by Edgar Allan Poe and for stories like Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.

Controversies, Personality, and Personal Life

Controversy was a constant companion throughout Beardsley's short career. His exploration of the erotic, the decadent, and the grotesque deliberately challenged Victorian sensibilities. His figures often seemed sexually ambiguous or androgynous, further unsettling contemporary viewers. Critics accused his work of being morbid, perverse, and unhealthy – accusations perhaps amplified by the knowledge of his own chronic illness.

Beardsley cultivated a public persona as a dandy, known for his immaculate dress, wit, and refined manners, much like his associate Oscar Wilde or the painter James McNeill Whistler. This carefully constructed image was part of the performance of Aestheticism, emphasizing artifice and style.

His personal life also attracted speculation. He had a close relationship with his sister, Mabel Beardsley, who became an actress. Rumors circulated, both during his life and after, about a possible incestuous relationship between them, fueled partly by the intense and sometimes strange depictions of male and female figures in his art. However, no concrete evidence supports these claims, and they remain speculative interpretations.

His circle included many key figures of the London art and literary scene of the 1890s, beyond Wilde and Burne-Jones. He was friends with the artist William Rothenstein, the writer and critic Max Beerbohm, and the artists Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon, who ran the Vale Press. He maintained contact with Robert Ross, a loyal friend of Wilde's and an art critic and dealer who supported Beardsley's work. He also formed friendships abroad, notably with the French painter Jacques-Émile Blanche, who painted his portrait, and he admired the work of French artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, whose depictions of Parisian nightlife shared a certain affinity with Beardsley's focus on modern, often risqué, subjects, and whose use of line and flat color planes also showed an engagement with Japanese art.

Illness, Final Years, and Conversion

Throughout his meteoric rise and prolific output, Beardsley battled worsening tuberculosis. The disease punctuated his life with periods of severe illness and hemorrhage. His awareness of his mortality may have contributed to the feverish intensity of his work and perhaps, as some contemporaries suggested, a tendency towards a more dissipated lifestyle, seeking sensation in the face of impending death.

In 1896, his health declined sharply. Seeking a better climate, he traveled to Brussels, Paris, and eventually the French Riviera. His final years were a nomadic existence, moving between resorts in search of relief, supported by friends and patrons like the publisher Leonard Smithers and the writer and patron André Raffalovich.

During this final period, in March 1897, Beardsley converted to Roman Catholicism. His motivations remain debated – perhaps a search for spiritual solace in the face of death, or influenced by Raffalovich and other Catholic friends like the poet John Gray. His conversion led to one of the most poignant episodes of his life. Shortly before his death, he wrote a desperate letter to Leonard Smithers: "Jesus is our Lord & Judge / Dear Friend, I implore you to destroy all copies of Lysistrata & bad drawings... By all that is holy all obscene drawings." Smithers, however, ignored the request, ensuring the survival of these controversial works.

Aubrey Beardsley died of tuberculosis in Menton, on the French Riviera, on March 16, 1898. He was only 25 years old.

Legacy and Influence

Despite the brevity of his career, Aubrey Beardsley left an indelible mark on art history. His unique style was a major force in the development of Art Nouveau, influencing artists across Europe and America. His emphasis on line, decorative pattern, and flattened space resonated with the movement's aesthetic principles. His work profoundly impacted poster design and graphic arts, demonstrating the power of black-and-white imagery in the age of mechanical reproduction.

His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent illustrators like Harry Clarke and Kay Nielsen, who adapted his intricate linearity to fairytale and fantasy subjects. Aspects of his style echoed in the Vienna Secession movement, particularly in the work of Gustav Klimt. Even artists seemingly far removed, like Pablo Picasso during his early Blue Period, showed a passing familiarity with Beardsley's linear elegance. The Glasgow School, including Charles Rennie Mackintosh, also absorbed elements of his stylized forms and decorative approach.

Beyond specific artistic movements, Beardsley's work continues to fascinate due to its technical brilliance, its daring subject matter, and its embodiment of the complex cultural currents of the fin de siècle. He remains a symbol of the Decadent movement, an artist who pushed the boundaries of taste and representation. His illustrations are instantly recognizable, possessing a strange, haunting beauty that is both elegant and unsettling.

Conclusion

Aubrey Beardsley's life was a paradox: tragically short yet intensely productive, marked by debilitating illness yet resulting in work of astonishing energy and precision. He burst onto the London art scene like a meteor, dazzling and disturbing in equal measure. As a master of line, he forged a unique visual language from diverse influences like Japanese prints, Pre-Raphaelite romanticism, and Rococo flourish. His work for Le Morte d'Arthur, Salome, The Yellow Book, and The Savoy defined the visual aesthetic of the 1890s Decadence.

Though often mired in controversy and cut down in his prime, Beardsley's artistic legacy proved enduring. He fundamentally changed the potential of black-and-white illustration and graphic design, paving the way for Art Nouveau and influencing generations of artists. His intricate, often provocative, and always elegant drawings continue to exert a powerful fascination, securing his place as one of the most original and influential artists of his time. His brief, brilliant reign as the "King of Line" left an unforgettable imprint on the landscape of modern art.