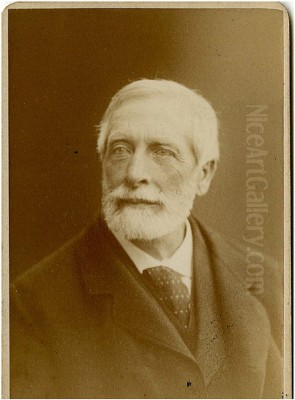

Barthélemy Menn stands as a significant innovator within the landscape of 19th-century Swiss art. His life and work bridged classical traditions with emerging modern approaches, particularly through his introduction and championing of plein-air (outdoor) painting and the principles of the paysage intime (intimate landscape) within Switzerland. As both a dedicated artist and an influential educator, Menn left an indelible mark on subsequent generations of Swiss painters.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Geneva

Born in Geneva on March 20, 1815, Barthélemy Menn was the youngest of four brothers. His family background reflected a blend of artisanal craft and rural prosperity; his father, Louis John Menn, was a confectioner hailing from the Grange Plain area, while his mother, Charlotte-Madeleine Bodmer, came from a well-off farming family in Vevey. This upbringing in Geneva, a city with its own burgeoning artistic identity, likely provided the initial backdrop for his developing sensibilities.

Menn's formal artistic journey began at the tender age of twelve, when he started taking drawing lessons from Jean Dubois, a local painter. This early instruction paved the way for his enrollment in the drawing school run by the Geneva Society of Arts (Société des Arts). Here, he further honed his foundational skills, becoming a fellow of the Society in 1831. During this period, he also studied under Jean-Léonard Lugardon, a respected Genevan painter who himself had trained under Barthélemy Grosson, connecting Menn indirectly to earlier artistic lineages.

Parisian Exposure and Formative Influences

Seeking broader horizons and more advanced training, Menn travelled to Paris in 1833. This move proved pivotal, immersing him in the vibrant, and often conflicting, artistic currents of the French capital. He gained entry into the prestigious studio of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, a leading figure of Neoclassicism. Studying under Ingres provided Menn with rigorous training in drawing and composition, instilling a deep respect for line and form derived from classical ideals.

However, Paris also exposed Menn to contrasting artistic philosophies. He was influenced by the burgeoning Romantic movement and its emphasis on emotion and individualism. Critically, he encountered the landscape painters of the Barbizon School. These artists, including figures like Camille Corot, rejected the idealized landscapes of Neoclassicism in favour of direct observation of nature, often painting outdoors (en plein air) in the Forest of Fontainebleau. This approach resonated deeply with Menn.

During his time in Paris, Menn moved within stimulating intellectual and artistic circles. He became acquainted with the writer George Sand and her associates, which included the composer Frédéric Chopin and the influential Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix. These connections broadened his cultural perspectives and likely reinforced his interest in expressive, less rigidly academic forms of art. His time spent copying masterpieces in the Louvre, including works by Raphael, Titian, and Velázquez, alongside classical sculptures and replicas of the Parthenon friezes, further deepened his understanding of art history and technique, profoundly shaping his evolving style.

Italian Interlude and Academic Recognition

In the autumn of 1834, Menn temporarily left the bustling Parisian art scene for Italy. This journey, a traditional step for aspiring artists seeking direct contact with classical antiquity and Renaissance masterpieces, allowed him to further develop his artistic vision away from the direct influence of his teachers. He absorbed the Italian light and landscape, experiences that would filter into his later work.

He returned to Paris in 1835, his skills and perspective enriched. His talent did not go unnoticed. In 1836, he achieved a significant milestone by becoming associated with the French Academy in Rome, during the period when his former master, Ingres, served as its director. This connection signifies his growing stature and his engagement with the established academic art world, even as his personal inclinations leaned towards newer approaches to landscape.

Return to Geneva: Artist and Educator

Menn returned to his native Geneva in 1844. While he brought back innovative ideas about landscape painting gleaned from his experiences in France and Italy, he encountered resistance from the more conservative elements within the local art establishment. Despite this opposition, he persevered, establishing himself as both a practicing artist and a compelling theorist.

His artistic skills were commissioned for significant projects, including decorative work at the historic Gruyères Castle, demonstrating his ability to work on a large scale and integrate his art within architectural contexts. However, his most enduring contribution arguably began in 1850 when he was appointed Professor at the Geneva School of Fine Arts (École des Beaux-Arts, now part of the Geneva University of Art and Design - HEAD).

Menn held this influential teaching position until his retirement in 1892, shaping the development of Swiss art for over four decades. He was not merely an instructor of technique but a mentor who imparted a distinct artistic philosophy. He encouraged his students to observe nature closely, to understand light and atmosphere, and to find personal expression within the landscape genre.

Artistic Style: Realism, Harmony, and Light

Barthélemy Menn's artistic style is characterized by its synthesis of classical structure and direct observation, heavily influenced by the Barbizon principles he embraced. He became a key proponent of plein-air painting in Switzerland, advocating for capturing the immediate sensations of light and atmosphere by working outdoors. This contrasted sharply with the studio-bound, often idealized or historical landscapes favoured by academic tradition.

He also championed the paysage intime, or intimate landscape. This approach focused on depicting modest, often unspectacular scenes – a corner of a forest, a quiet pasture, a bend in a river – imbued with a sense of personal feeling and tranquility. Menn avoided dramatic exaggeration or overt romanticism, preferring instead to emphasize the truthful rendering of topography, the subtle play of light on surfaces, and the inherent harmony of the natural world.

His deep study of Old Masters like Raphael, Titian, Velázquez, Veronese, Claude Lorrain, and Rubens informed his technique, particularly in composition and the handling of paint. Yet, his engagement with classical forms, such as the Parthenon friezes he meticulously copied, translated not into Neoclassical stiffness, but into a sense of underlying order and balance within his naturalistic scenes. There's an anecdote that Menn, in his later years, destroyed many of his earlier works, suggesting a rigorous self-criticism and a continuous search for refinement in his artistic expression, even resorting to copying masters like Gerard Dou to further explore technique.

Menn's overarching artistic philosophy sought a profound connection between art, the natural world, and a sense of universal harmony. He believed art could serve as a bridge between the transient human experience and the eternal, aiming to capture not just the appearance of nature, but its deeper essence and its calming, restorative power.

Representative Works

While Menn was highly self-critical and perhaps less prolific in terms of major exhibition pieces compared to some contemporaries, his surviving works exemplify his distinct approach.

Peasant's Breakfast ("Bauernmahl"): This work likely reflects the paysage intime sensibility extended to genre scenes, depicting a quiet moment of Swiss rural life. It would showcase his focus on realistic portrayal, subdued atmosphere, and finding significance in everyday moments, rendered with sensitivity to light and texture.

Dialogue in the Wood: As suggested by the title, this landscape would focus on a specific, perhaps enclosed, woodland scene. It exemplifies his dedication to capturing the intricacies of nature – the structure of trees, the quality of light filtering through leaves, the texture of the forest floor. Such works demonstrate his skill in rendering atmosphere and his ability to create a sense of quiet contemplation through the depiction of a specific, intimately observed natural setting.

His oeuvre primarily consists of landscapes capturing the Swiss countryside, particularly the areas around Geneva and the Alps. These paintings are noted for their subtle colour palettes, careful composition, and profound sense of peace, reflecting his philosophical belief in nature's harmony.

Network and Relationships: Collaboration and Contrast

Menn's position as a long-serving professor placed him at the center of Geneva's art world, fostering relationships based on mentorship. His influence on students like Ferdinand Hodler, Edouard Vallet, and Edouard Castres was profound. He provided them with solid technical grounding and exposure to modern ideas about landscape painting. However, he also encouraged their individual development. Hodler, for instance, while clearly benefiting from Menn's teaching, developed a distinct Symbolist style ("Parallelism") that diverged significantly, eventually seeking recognition in Paris after facing initial difficulties in Switzerland.

His earlier connections in Paris linked him to major figures like Ingres and Delacroix, placing him at the crossroads of Neoclassicism and Romanticism. His association with the Barbizon painters, including friendships or acquaintances with artists like Camille Corot and potentially Karl Bodmer, situated him within the progressive landscape movement of the mid-19th century. These connections formed part of his artistic network, providing stimulus and context for his own work.

While specific instances of direct competition are not heavily documented in the provided sources, Menn's innovative approach inherently placed him in contrast with more traditional academic painters in Switzerland. His emphasis on direct observation, plein-air methods, and the paysage intime challenged the prevailing tastes for historical or highly idealized Alpine scenery. This stylistic divergence represented a form of artistic competition, pushing the boundaries of accepted landscape painting in his homeland.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Barthélemy Menn died on October 15, 1893, in Geneva. His legacy extends far beyond his own canvases. As a painter, he was instrumental in introducing and legitimizing modern approaches to landscape painting in Switzerland, shifting the focus towards direct observation, atmospheric effects, and intimate portrayals of nature. He skillfully blended respect for tradition, learned through copying masters and studying under Ingres, with the innovative spirit of the Barbizon school.

His most significant impact, however, may lie in his role as an educator. For over forty years, he guided and inspired generations of Swiss artists at the Geneva School of Fine Arts. His teaching emphasized rigorous observation, technical proficiency, and the pursuit of personal artistic vision grounded in the study of nature. Figures like Ferdinand Hodler, who became one of Switzerland's most celebrated painters, owed a significant debt to Menn's foundational instruction, even as they forged their own unique paths.

Menn's dedication to his artistic principles, his quiet insistence on capturing the harmony and truth of the natural world, and his profound influence as a teacher solidify his position as a crucial transitional figure in Swiss art history. He helped pave the way for modernism in Switzerland, leaving behind a legacy of sensitive landscape painting and a lineage of accomplished students who would further shape the course of European art.