Bernard Picart stands as a significant figure in the history of European art, particularly renowned for his prolific work as an engraver and illustrator during the late Baroque and early Enlightenment periods. Born in Paris in 1673 and later flourishing in Amsterdam until his death in 1733, Picart's life and career traversed geographical, cultural, and religious boundaries. His meticulous technique, combined with a keen observational eye and intellectual curiosity, resulted in a vast body of work that not only captured the aesthetic sensibilities of his time but also contributed significantly to the dissemination of knowledge and the burgeoning field of comparative religion. His legacy is cemented by his masterful engravings, most notably those found in the monumental Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Bernard Picart was born into an artistic milieu in Paris, the heart of French cultural life under Louis XIV. His father, Etienne Picart (1632-1721), known as 'Le Romain' (The Roman) due to his time spent studying in Rome, was himself a respected engraver. This familial connection undoubtedly provided young Bernard with early exposure to the craft and techniques of printmaking. His innate talent was evident from a young age, leading him to formal training at the prestigious Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture.

At the Academy, Picart studied under prominent figures associated with the grand style favoured by the French court. While direct tutelage details can be debated, influences from masters like Charles Le Brun (1619-1690), the dominant figure in French art and director of the Academy, are undeniable in Picart's early classical grounding. Some sources also suggest connections to instructors like Bon Boullogne (1649-1717). His precociousness was confirmed when, at the age of sixteen, he reportedly received honours or won an award from the Academy, signalling the arrival of a promising talent in the competitive Parisian art scene. His early work reflected the prevailing French classical taste, focusing on historical, mythological, and religious subjects executed with technical precision.

The Move to Amsterdam: A New Chapter

Around 1710 or 1711, Bernard Picart made a pivotal decision to leave Paris and relocate to Amsterdam. This move was likely motivated by a confluence of factors, both personal and professional. Religiously, Picart, originally from a Catholic family, converted to Protestantism. As a Huguenot, the atmosphere in France following Louis XIV's Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685), which stripped Protestants of their rights, remained restrictive, even decades later. Amsterdam, in contrast, was renowned for its relative religious tolerance, offering a haven for dissenting faiths.

Professionally, Amsterdam was a global centre for publishing and the book trade. Its free press and dynamic market provided fertile ground for an artist specializing in illustration and engraving. Picart recognized the opportunities available in the Dutch Republic, where demand for illustrated books – ranging from Bibles and classical texts to scientific treatises and travelogues – was high. Settling in Amsterdam allowed him to establish a successful workshop, collaborate with publishers, and gain greater artistic and financial independence than might have been possible within the more rigid structure of the French academic system. He quickly integrated into the city's vibrant artistic and intellectual life.

Magnum Opus: Ceremonies and Religious Customs

Bernard Picart's most enduring legacy is arguably his contribution to Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde (Ceremonies and Religious Customs of All the Peoples of the World). This ambitious, multi-volume work, published primarily between 1723 and 1743 (with Picart working on it until his death in 1733), was a landmark publication of the Enlightenment. It aimed to provide a comprehensive, illustrated survey of the world's religions, including those of Asia, Africa, and the Americas, alongside various Christian denominations and Judaism.

Picart collaborated closely on this project with the writer and publisher Jean-Frédéric Bernard (1683-1744), a fellow Huguenot émigré. While Bernard compiled and wrote the text, Picart designed and executed the majority of the more than 250 engravings. These plates are remarkable for their detail, ethnographic curiosity, and attempt at objective representation, although inevitably viewed through a European lens. The work covered rituals, festivals, clerical dress, and places of worship, bringing distant cultures and diverse practices vividly to life for a European audience.

The Cérémonies was groundbreaking in its scope and comparative approach. It treated non-Christian religions with a degree of seriousness and detail previously uncommon, reflecting the Enlightenment's growing interest in human diversity and empirical observation. Picart's engravings, such as the depiction of a Jewish Seder feast, Catholic processions, Islamic prayer, or indigenous American funeral rites, became iconic visual references. The work was immensely popular and influential, translated into several languages, shaping European understanding (and misunderstanding) of global religions for generations.

A Prolific Engraver: Diverse Works

Beyond the monumental Cérémonies, Picart's output was vast and varied. He was a highly sought-after book illustrator, contributing plates to numerous publications, including editions of Ovid, Racine, and various historical accounts. His skill extended to portraiture, allegorical compositions, and designs for decorative elements. His technical mastery allowed him to work fluidly across different genres and subject matters.

One particularly fascinating project was Impostures innocentes (Innocent Impostures), a collection of seventy-eight engravings published posthumously by his widow in 1734. This work consisted of Picart's meticulous copies or interpretations of drawings and prints by Old Masters and contemporaries, drawn from famous Dutch collections. Artists imitated included Renaissance and Baroque giants like Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), Guido Reni (1575-1642), Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), and Annibale Carracci (1560-1609).

The title itself, Innocent Impostures, suggests a complex attitude towards imitation. On one hand, it was a demonstration of Picart's extraordinary technical virtuosity, his ability to capture the distinct styles of diverse masters. On the other, it perhaps carried a subtle commentary on the nature of originality and reproduction in the age of printmaking, or even a playful challenge to connoisseurs. These "impostures" were highly regarded for their fidelity and skill.

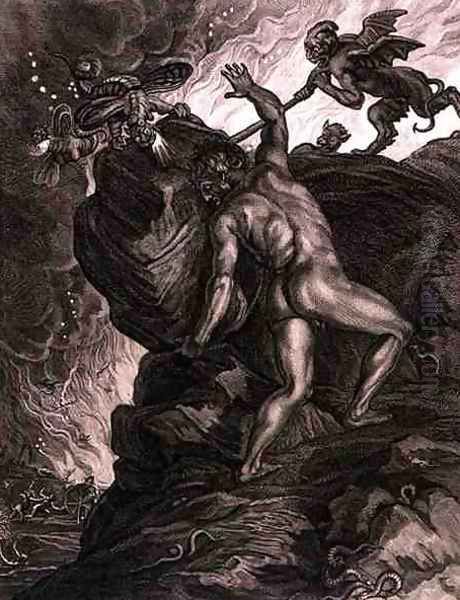

Other notable works showcase his range. Le Temple des Muses (The Temple of the Muses), published in 1733, featured sixty plates illustrating classical myths, primarily from Ovid's Metamorphoses, demonstrating his command of mythological narrative and the idealized human form. Engravings like Sisyphus Pushing His Stone Up a Mountain (1731) further exemplify his engagement with classical themes. He also produced allegorical works related to contemporary events, such as the Allegory of the History of the French Monarchy.

Artistic Style: Technique and Aesthetics

Bernard Picart's artistic style is characterized by its clarity, precision, and remarkable level of detail. He was a master of the engraving and etching techniques, often combining both to achieve subtle variations in tone and texture. His line work is typically clean and controlled, allowing for intricate rendering of fabrics, architectural elements, and human anatomy. This meticulousness lent an air of accuracy and authenticity to his illustrations, particularly important for works like Cérémonies.

Stylistically, Picart's work represents a bridge between the French classicism of his training and the influences he absorbed in the Netherlands. From his French background, particularly the influence of Le Brun, he retained a sense of compositional order, elegant figure drawing, and a certain theatricality in his narrative scenes. However, his time in Amsterdam exposed him to the Dutch tradition's emphasis on realism, detailed observation, and genre scenes.

His style can be seen as a refined, late Baroque classicism, less overtly dramatic than some contemporaries but possessing a distinct elegance and intellectual clarity. While capable of dynamic compositions, his primary focus often seems to be on informative representation, especially in his illustrative work. Compared to the more flamboyant Dutch engraver Romeyn de Hooghe (1645-1708), Picart's style often appears more restrained and polished, though equally detailed. He successfully synthesized various influences into a distinctive and highly effective graphic language.

Influences, Imitations, and Artistic Dialogue

Picart's career was deeply embedded in the artistic dialogues of his time, particularly concerning the relationship between original creation and reproduction. His Impostures innocentes explicitly engaged with the legacy of past masters. By imitating artists like Rembrandt, Rubens, Van Dyck, and Poussin, he was not merely copying but participating in a long tradition of learning and homage through reproduction. Engraving was the primary means by which paintings and drawings were disseminated to a wider audience, and reproductive engravers played a crucial role in shaping art historical canons.

His work demonstrates a thorough understanding of the stylistic nuances of the artists he imitated. His ability to capture the loose, expressive line of a Rembrandt sketch or the polished classicism of a Poussin drawing in the demanding medium of engraving was exceptional. This practice also placed him in dialogue with contemporary collectors. Access to major collections in Amsterdam and potentially knowledge of Parisian collections, like that of the famous connoisseur Pierre Crozat (1665-1740), whose collection was extensively documented, would have been crucial for projects like Impostures innocentes.

Beyond direct imitation, Picart was influenced by the broader artistic currents of his time. The French academic tradition provided his foundation, while the Dutch environment offered new subjects and perspectives. He operated within a network of artists, publishers, and intellectuals. While direct collaborations beyond Jean-Frédéric Bernard are less documented, his position in the bustling Amsterdam art market meant he was certainly aware of and responding to the work of Dutch contemporaries, perhaps engravers like members of the Houbraken family (Arnold Houbraken, 1660-1719, and his son Jacobus Houbraken, 1698-1780) or figures influenced by the classicism of Gerard de Lairesse (1641-1711). His father, Etienne Picart, and French contemporaries like Sébastien Leclerc (1637-1714) also form part of his artistic lineage.

Faith and Perspective

Bernard Picart's conversion from Catholicism to Protestantism was a significant aspect of his life and likely influenced his worldview and career trajectory. His move to the more tolerant Dutch Republic provided him with the freedom to practice his faith openly. This personal religious journey may have also informed the perspective evident in his work, particularly the Cérémonies. While striving for a degree of objectivity, his position as a Protestant émigré in a multi-confessional society likely fostered a particular interest in religious diversity and the comparative study of rituals.

Some scholars suggest that his portrayal of Catholic ceremonies, while detailed, occasionally carries subtle critiques, reflecting Huguenot perspectives on perceived Catholic excesses. Conversely, his depictions of Jewish life in Amsterdam, though sometimes relying on established visual types, were among the most detailed and sympathetic of their time, perhaps reflecting the relative integration of the Sephardic community in Amsterdam and Picart's own position as part of a minority faith group.

His engagement with religious themes extended beyond the Cérémonies. He illustrated Bibles and other religious texts throughout his career. His faith seems intertwined with the Enlightenment values of reason, observation, and tolerance that permeate much of his work. He used his artistic skill not just for aesthetic ends but also as a tool for documenting, comparing, and understanding the complex tapestry of human belief systems.

Legacy and Enduring Significance

Bernard Picart died in Amsterdam in 1733, leaving behind a rich and influential body of work. His widow continued his publishing activities, ensuring the dissemination of works like Impostures innocentes. Picart's significance lies in several key areas. Firstly, he was a supremely gifted engraver, whose technical mastery set a high standard for book illustration in the 18th century. His clarity and precision made his images highly effective tools for communication and education.

Secondly, through Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde, he made a lasting contribution to the visual culture of the Enlightenment and the early study of comparative religion. His engravings provided a visual vocabulary for discussing and understanding global religious diversity, influencing European perceptions for well over a century. The work remains a crucial resource for historians studying early modern ethnography and religious representation.

Thirdly, his career exemplifies the transnational nature of art and ideas in the early 18th century. As a Frenchman who found success and freedom in the Dutch Republic, he synthesized different artistic traditions and participated actively in the intellectual currents of his adopted home. His work bridges the late Baroque and the Enlightenment, French classicism and Dutch observational traditions. Bernard Picart remains a pivotal figure, recognized for his technical brilliance, his intellectual curiosity, and his role in visually shaping the understanding of a complex world.