Bernhard Strigel stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of German art during the pivotal period of transition from the late Gothic era to the burgeoning Renaissance. Active primarily in the Swabian city of Memmingen and later at the Imperial court, Strigel's oeuvre, particularly his insightful portraiture and devotional works, reflects the artistic currents of his time while retaining a distinct personal character. His life and career offer a fascinating window into the artistic, religious, and political landscape of Southern Germany at the turn of the 16th century.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Memmingen

Bernhard Strigel was born in Memmingen, a prosperous Free Imperial City in Swabia, around 1460 or 1461. He hailed from a family deeply embedded in the artistic traditions of the region. His father, Hans Strigel the Elder, was a painter, and his grandfather, Hans Strigel the Middle, was also an artist. Furthermore, his uncle, Ivo Strigel, was a respected sculptor. This familial environment undoubtedly provided Bernhard with his initial artistic training and immersion in the craft from a young age. The Strigel workshop was a prominent artistic force in Memmingen, undertaking various commissions, including altarpieces and other religious works.

The artistic milieu of Swabia in the late 15th century was still heavily influenced by the late Gothic style, characterized by its expressive intensity, elongated figures, and rich decorative patterns. Early in his career, Strigel's work bore the hallmarks of this tradition. A key figure often cited as an influence on, or possibly even a teacher of, the young Strigel is Bartholomäus Zeitblom. Zeitblom, active in nearby Ulm, was a leading master of the Ulm School, known for his serene figures and refined color palettes. It is plausible that Strigel spent some time in Ulm, absorbing the stylistic nuances prevalent there. The Ulm School itself was part of a broader network of artistic exchange in Southern Germany, with artists like Michael Pacher in the Tyrol also pushing boundaries with their synthesis of painting and sculpture.

Strigel's artistic development did not occur in isolation. The late 15th century saw increasing contact with artistic innovations from other regions, particularly the Netherlands. The meticulous realism, mastery of oil paint, and nuanced depiction of light and texture pioneered by Netherlandish masters such as Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, and later Hugo van der Goes and Dieric Bouts, began to permeate German art. Martin Schongauer, a painter and engraver from Colmar in Alsace, was particularly instrumental in disseminating these influences through his widely circulated prints, which Strigel would almost certainly have known. Schongauer's refined technique and expressive power left a significant mark on many German artists of Strigel's generation.

Emergence as an Independent Master

By the 1480s, Bernhard Strigel was actively working as an independent master in Memmingen. He established his own workshop and began to build a reputation that extended beyond his native city. His output was diverse, encompassing large-scale altarpieces, smaller devotional panels, and, increasingly, portraits. Memmingen, as a thriving commercial center, provided a steady stream of commissions from the church, civic bodies, and wealthy burghers.

His religious paintings from this period, while rooted in Gothic conventions, began to show a greater interest in naturalistic representation and psychological depth. Works like the Virgin Mary Altarpiece (the specific location of which can vary in sources, often referring to components of larger, now-dismantled altarpieces) would have demonstrated his ability to handle complex iconographic programs and create emotionally resonant scenes. He often collaborated with sculptors, a common practice for large altarpiece commissions, including the sculptor Hans Thoman, who was active in Ulm and the surrounding region. This interplay between painted panels and sculpted figures was a hallmark of German altarpieces of the period.

Strigel's style during these formative years shows a gradual assimilation of Renaissance ideals, likely through exposure to Italian art via prints or travelling artists, and the continued influence of Netherlandish realism. The emphasis on individualized features, a more naturalistic rendering of drapery, and a growing concern for spatial coherence began to distinguish his work. He was not as revolutionary as Albrecht Dürer in Nuremberg, who was actively engaging with Italian Renaissance theory, but Strigel was clearly a perceptive artist, absorbing and adapting new ideas within his own established framework.

The Art of Portraiture: Strigel's Enduring Contribution

While Strigel was a versatile artist, it is arguably in the realm of portraiture that he made his most distinctive and enduring contributions. He developed a remarkable ability to capture not only the likeness of his sitters but also a sense of their personality and social standing. His portraits are characterized by their clarity, meticulous attention to detail in costume and accessories, and often a direct, engaging gaze from the subject.

Among his notable early portraits is the Portrait of Conrad Rehlinger (1517), now housed in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich. Rehlinger was a prominent Augsburg merchant, and Strigel depicts him with a sober dignity, his status conveyed through his attire and composed demeanor. The painting showcases Strigel's skill in rendering textures, from the fur collar to the soft fabric of the sitter's cap.

His talent for portraiture did not go unnoticed by the highest echelons of society. This led to one of the most significant phases of his career: his association with the Habsburg Emperor Maximilian I. The Emperor was a renowned patron of the arts, employing artists to project his image and legacy. Figures like Albrecht Dürer, Hans Burgkmair the Elder, Lucas Cranach the Elder, and Albrecht Altdorfer all received commissions from Maximilian. Strigel joined this illustrious company, serving as a court painter, particularly between 1515 and 1520, during which time he spent periods in Vienna and other Habsburg centers.

At the Imperial Court: Portraits of Power

Strigel's tenure as a court painter to Emperor Maximilian I marked a high point in his career. He produced several important portraits of the Emperor and his family, which served as crucial tools of dynastic representation and political propaganda. Perhaps the most famous of these is the Portrait of Emperor Maximilian I and his Family (circa 1515-1520), now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. This group portrait includes Maximilian, his first wife Mary of Burgundy (posthumously), his son Philip the Fair, his grandsons Charles (later Emperor Charles V) and Ferdinand (later Emperor Ferdinand I), and his granddaughter's husband, Louis II of Hungary. The painting is a powerful statement of Habsburg lineage and imperial ambition. Strigel masterfully arranges the figures, differentiating their ages and personalities while maintaining a sense of dynastic unity.

He also painted individual portraits of Maximilian, such as the iconic Portrait of Emperor Maximilian I (versions exist, one notable example also in the Kunsthistorisches Museum), which presents the Emperor in a dignified and authoritative manner, often adorned with the symbols of his office. Another significant work from this period is the Portrait of King Louis II of Bohemia and Hungary as a Child (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), a charming yet formal depiction of the young monarch who was linked to the Habsburgs through marriage.

Working for the Imperial court would have exposed Strigel to a wider range of artistic influences and a sophisticated circle of patrons and fellow artists. His style in these courtly portraits often combines a Northern European attention to detail with a certain grandeur befitting his subjects. He demonstrated a keen psychological insight, capturing the complexities of his sitters beyond mere official representation. His ability to render the opulent fabrics, jewels, and insignia of power was highly valued. The precision and clarity of his portraits made them effective instruments for conveying imperial authority and dynastic continuity across the vast Habsburg territories.

Religious Works and Altarpieces: Faith and Artistry

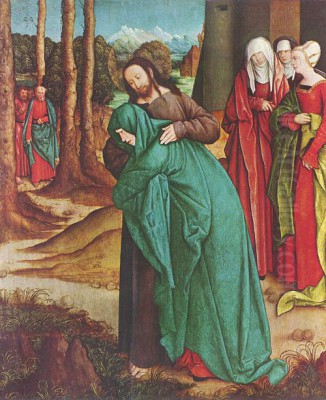

Alongside his flourishing career as a portraitist, Bernhard Strigel continued to produce religious paintings and altarpieces throughout his life. These works reflect the devotional practices of the time and showcase his ability to translate complex theological themes into compelling visual narratives. His religious art, like his portraits, evolved from a more distinctly Gothic style towards a greater embrace of Renaissance principles of clarity, balance, and naturalism, though always retaining a characteristic German expressiveness.

One notable example of his religious work is The Annunciation, now in the Prado Museum, Madrid. This panel, likely part of a larger altarpiece, depicts the Archangel Gabriel announcing the divine conception to the Virgin Mary. Strigel's treatment of the scene is imbued with a quiet solemnity. The figures are rendered with a gentle grace, and the composition demonstrates an understanding of perspective and spatial depth. The use of light and color contributes to the ethereal atmosphere of the miraculous event.

Another significant religious work is The Holy Family (often identified as The Holy Family with St. Anne, St. Joachim, and the young St. John the Baptist), housed in the Musée d'Unterlinden in Colmar. This painting displays a tender intimacy between the figures, a hallmark of devotional art intended to foster personal piety. The composition is carefully balanced, and the figures, while idealized, possess a human warmth. The inclusion of saints Anne and Joachim, the Virgin Mary's parents, emphasizes the theme of lineage and family, a popular subject in the period.

Strigel's workshop in Memmingen would have been responsible for numerous altarpieces for churches in Swabia and beyond. Many of these large-scale works have unfortunately been lost or dismantled over time, particularly during the iconoclastic fervor of the Protestant Reformation, which gained traction in Southern Germany during Strigel's later years. The surviving panels and fragments, however, attest to his skill in narrative composition, his rich color sense, and his ability to convey deep religious feeling. His style in these works can be compared to that of other South German contemporaries like Hans Holbein the Elder of Augsburg, who also navigated the transition from Gothic to Renaissance aesthetics in his religious commissions.

Later Career, Civic Life, and Workshop

After his period of service to Emperor Maximilian I, Strigel remained a highly respected artist. While he continued to undertake prestigious commissions, including portraits of nobility and wealthy clergy, he was also deeply involved in the civic life of Memmingen. He held various municipal positions, serving as a guild member and representing the city in legal and diplomatic matters. This active participation in public affairs indicates his esteemed status within the community, not just as an artist but as a prominent citizen.

His artistic style in his later years consolidated the gains made during his exposure to the Imperial court and broader European trends. His portraits maintained their characteristic clarity and psychological acuity. He continued to refine his technique, achieving a smooth, enamel-like finish in his paintings. The influence of Netherlandish art remained apparent, particularly in the meticulous rendering of textures and the subtle play of light. While he may not have embraced the more overt classicism seen in the work of some of his Italian contemporaries or even German artists like Dürer who had travelled extensively in Italy, Strigel forged a distinctive path that blended Northern traditions with Renaissance sensibilities.

The Strigel workshop in Memmingen likely continued to be a busy enterprise, training apprentices and producing a range of artworks. The extent of workshop participation in his later works is a subject of art historical discussion, as is common with prolific masters of the period. After his death, his studio was reportedly taken over by his brother-in-law, Hans Goldschmidt, ensuring a continuation of the artistic legacy, at least for a time.

Bernhard Strigel passed away in Memmingen in 1528, at the age of around 67 or 68. He left behind a significant body of work that testifies to his skill, versatility, and adaptability. His death occurred at a time of profound religious and social upheaval, with the Reformation reshaping the artistic landscape of Germany. The demand for traditional forms of religious art declined in many Protestant regions, impacting artists who specialized in these genres.

Legacy and Art Historical Assessment

Bernhard Strigel's legacy is primarily secured by his exceptional portraits, particularly those of Emperor Maximilian I and his circle, which are invaluable historical documents as well as accomplished works of art. These paintings provide a vivid glimpse into the personalities and power structures of the Holy Roman Empire at a critical juncture. His ability to combine formal representation with individual characterization places him among the leading German portraitists of his generation, alongside figures like Lucas Cranach the Elder and Hans Holbein the Younger (though Holbein's international career would soon eclipse many of his German contemporaries).

While some of his larger religious works have been lost, the surviving examples demonstrate his competence in handling complex iconographic programs and his sensitivity to devotional needs. His style, which successfully navigated the transition from the expressive intensity of late Gothic art to the more naturalistic and ordered aesthetics of the Renaissance, reflects the broader artistic transformations occurring across Northern Europe. He may not have been an innovator on the scale of Dürer or Grünewald, but his consistent quality and distinctive personal style earned him considerable renown in his lifetime.

In art historical scholarship, Strigel is recognized as a key representative of the Swabian school of painting. His works are found in major museums across Europe and North America, including the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, the Prado in Madrid, and the National Gallery in London. His paintings occasionally appear at auction, sometimes commanding significant prices, as evidenced by the sale of a Portrait of an Angel (dated around 1520) in Toulouse, which fetched a high sum, underscoring the continued appreciation for his artistry.

Strigel's career illustrates the life of a successful master in a prosperous German city, capable of serving both local patrons and the highest imperial authority. He absorbed influences from various sources—local traditions, Netherlandish innovations, and the broader currents of the Renaissance—to forge a style that was both representative of its time and uniquely his own. As an art historian, one appreciates Strigel for his technical skill, his psychological insight in portraiture, and his role as a chronicler of an era of profound change. His contribution to the German Renaissance, particularly in Swabia, remains a testament to the rich and diverse artistic production of the period.