Cesare Bentivoglio, an Italian painter active during the late nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries, remains a figure somewhat veiled by the mists of time. While records confirm his existence and activity, detailed biographical accounts are notably scarce, as indicated by available research materials. Born in Genoa in 1868, he lived until 1952, a lifespan bridging the unification of Italy, the turn of the century, and the tumultuous first half of the 20th century. Despite the limited personal documentation, his name immediately connects him to one of Italy's most historically significant noble families – the Bentivoglio of Bologna – casting a long shadow of Renaissance power and intrigue over his more modern artistic endeavors.

Understanding Cesare Bentivoglio the painter requires acknowledging the profound historical weight carried by his surname. His connection, likely as a descendant, is to the Bentivoglio dynasty that dominated Bologna during the vibrant, yet volatile, Italian Renaissance. This lineage provides a rich backdrop against which his own life and work, however sparsely documented, can be contextualized, even if he himself did not participate in the grand political dramas of his ancestors. His identity is thus twofold: an artist working in a specific time and place, and the inheritor of a name synonymous with Italian history.

Origins and the Bentivoglio Lineage

While specific details about Cesare Bentivoglio's immediate parentage and upbringing are not readily available in the consulted sources, his birth in Genoa in 1868 is noted. This places his origins in the important port city of Liguria, a region whose landscapes would feature prominently in his known artistic output. However, the name Bentivoglio inevitably draws attention eastward, to Bologna in Emilia-Romagna, the family's historical seat of power.

The Bentivoglio family's story is deeply woven into the fabric of Italian Renaissance history. They were a noble house whose origins, according to family tradition, traced back to King Enzio of Sardinia (c. 1218–1272), an illegitimate son of the formidable Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II Hohenstaufen. Legend holds that the family name derived from Enzio's romantic declaration, "Ben ti voglio" ("I am fond of you"), supposedly uttered to a local peasant girl from a castle near Bologna, which became the family's ancestral heartland.

By the 14th century, the Bentivoglio had established themselves as prominent citizens in Bologna. They rose through the ranks of civic power, holding positions such as Gonfaloniere di Giustizia (Standard-bearer of Justice), a key role in the city's republican government. Their influence grew steadily, navigating the complex political landscape of papal ambitions, local rivalries, and the burgeoning power of condottieri (mercenary captains).

The family reached the zenith of its power in the 15th century, effectively becoming the hereditary rulers, or Signori, of Bologna. Figures like Sante Bentivoglio (1424–1463) and, most notably, Giovanni II Bentivoglio (1443–1508) presided over a period of relative stability and cultural flourishing in the city. Under their rule, Bologna experienced a golden age, marked by significant architectural projects, patronage of the arts, and the maintenance of a sophisticated court that rivaled others in Italy.

It is crucial, however, to distinguish the historical prominence of these Renaissance figures from the life of Cesare Bentivoglio (1868-1952). The available sources explicitly state that the painter Cesare Bentivoglio did not play a significant role in major historical events. His life unfolded centuries after the peak of his family's political power, in a vastly different Italy. His legacy lies not in statecraft or warfare, but in the canvases he created.

The Historical Context of the Bentivoglio Family

To fully appreciate the background associated with Cesare Bentivoglio's name, a deeper look into the historical context of his ancestors is warranted. The Bentivoglio ruled Bologna during a period of intense political fragmentation and shifting alliances in Italy. Their position was often precarious, balanced between the authority of the Papal States (which claimed sovereignty over Bologna), the ambitions of powerful neighboring states like Milan and Florence, and internal factions within the city itself.

Giovanni II Bentivoglio's long reign (1463–1506) exemplifies the family's power and its eventual vulnerability. He skillfully managed alliances, maintained a splendid court, and fostered the arts and the University of Bologna. His wife, Ginevra Sforza (sister of the Duke of Milan), connected the family to another major Italian dynasty, highlighting the web of aristocratic marriages used to consolidate power. The Palazzo Bentivoglio in Bologna became a symbol of their status, renowned for its scale and artistic decoration, reflecting the family's wealth and cultural aspirations.

However, Giovanni II's rule was also marked by ruthlessness and political maneuvering necessary for survival. The family faced numerous conspiracies and challenges from rival Bolognese families like the Malvezzi and Marescotti. Their most formidable external threat emerged in the figure of Cesare Borgia, Duke of Valentinois and son of Pope Alexander VI. Borgia, carving out a state for himself in central Italy with papal backing, set his sights on Bologna in the early 1500s.

Giovanni II initially navigated the Borgia threat through diplomacy and temporary alliances. In 1502, he even participated briefly in the Congiura della Magione, a conspiracy of condottieri against Cesare Borgia. However, fearing French intervention on Borgia's side, Giovanni II ultimately betrayed his co-conspirators and reconciled with Borgia, albeit temporarily. This period was fraught with tension and shifting loyalties, characteristic of the era's power politics immortalized by Niccolò Machiavelli.

The Bentivoglio's downfall came not at the hands of Borgia (whose power waned after his father's death), but from Pope Julius II, the "Warrior Pope." Determined to reassert direct papal control over Bologna, Julius II personally led an army against the city in 1506. Facing overwhelming force and internal dissent, Giovanni II and his family were forced to flee. The Pope entered Bologna in triumph, ending the Bentivoglio signoria. The magnificent Palazzo Bentivoglio was subsequently destroyed by the enraged populace.

Giovanni II died in exile in Milan in 1508. His sons made several attempts to recapture Bologna in the following years, briefly succeeding in 1511-1512 with French support during the War of the League of Cambrai, but papal authority was ultimately restored. The family's political power in Bologna was broken, though branches of the Bentivoglio continued to exist in other parts of Italy, carrying their noble lineage into subsequent centuries. This dramatic history of power, patronage, intrigue, and eventual decline forms the ancestral backdrop for the later, more modest artistic career of Cesare Bentivoglio of Genoa.

Artistic Career and Known Works

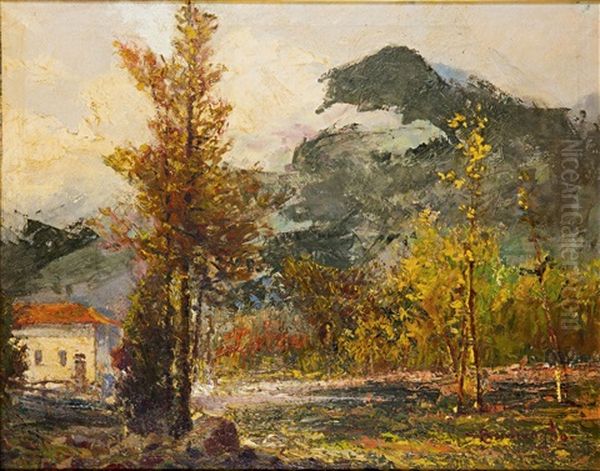

Returning to Cesare Bentivoglio (1868-1952), the painter, the available information focuses primarily on his artistic output rather than his personal life. He is identified as an Italian painter, born in Genoa, who worked predominantly in oil on canvas, although at least one work in pastel on board is recorded. His subject matter appears to have centered on landscapes, particularly scenes from his native Liguria, and potentially seascapes and portraits, though landscape examples are more frequently cited in the sources.

Several specific works are attributed to him, often appearing in auction records, which provide valuable clues about his activity and market presence. One notable piece is Riviera ligure (Ligurian Riviera). This oil on canvas, measuring 46 x 65.5 cm, bears the signature "C. Bentivoglio" in the lower right corner. Auction estimates placed its value between €500 and €700, suggesting a recognized, if perhaps not premier-level, market standing for his work during the period it was assessed.

Another documented painting is Marina con velieri all'orizzonte (Seascape with Sailing Ships on the Horizon). This work, measuring 45 x 66 cm, indicates his engagement with maritime themes, a natural subject for a Genoese artist. Its estimated auction value was higher, ranging from €1500 to €2000, potentially reflecting a larger scale, higher quality, or greater demand for this particular piece or subject matter.

The use of pastel is confirmed by the work Paesaggio dell'entroterra ligure (Landscape of the Ligurian Hinterland). This piece, executed on board and measuring 67 x 49.5 cm, carried an estimate of €1000-€2000. The medium suggests a versatility beyond oil painting and perhaps an interest in capturing different atmospheric effects or textures, often associated with pastel work. The subject again points to his focus on the Ligurian region, exploring its inland scenery as well as its famous coastline.

General titles like Marina ligure (Ligurian Seascape) and Paesaggio ligure (Ligurian Landscape) also appear in auction listings connected to Cesare Bentivoglio, reinforcing his reputation as a painter of his home region. Sources also mention other attributed works, such as a painting depicting a carriage and another seascape featuring Lavagna (a town on the Ligurian coast), bearing signatures like "C Bentivoglio." One source intriguingly notes a signature "C Mancini" alongside "C Bentivoglio" on one of these, raising questions about potential collaboration, misattribution, or perhaps different artists with similar names, though the source lists it under Bentivoglio.

One point of confusion arises concerning a painting titled Vele in laguna (Sails in the Lagoon), dated 1875. While mentioned in the context of Cesare Bentivoglio's works in one source, the same source explicitly states it was completed by the artist Beppe Ciardi (1875-1932). Furthermore, given Cesare Bentivoglio's birth year of 1868, he would have been only seven years old in 1875, making it highly improbable that this is his work. It seems likely this is either a misattribution in the source compilation or a reference to a work by Ciardi perhaps owned by or associated with the Bentivoglio name in some other context. It should not be confidently listed among Cesare Bentivoglio's own creations.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Based on the limited descriptions and the nature of the works cited, we can infer some aspects of Cesare Bentivoglio's artistic style, though a detailed analysis is hampered by the lack of critical reviews or extensive reproductions in the consulted materials. His preference for Ligurian landscapes and seascapes suggests a focus on naturalistic representation, capturing the distinctive light, coastline, and terrain of the region. This aligns with a strong tradition of landscape painting in Italy during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

His use of both oil on canvas and pastel on board indicates technical versatility. Oil painting would allow for rich colors, detailed rendering, and durable finishes, suitable for capturing the solidity of landscapes or the dynamic movement of the sea. The mention of Paesaggio dell'entroterra ligure as a pastel suggests an ability to work with a medium known for its immediacy, vibrant color, and potential for soft, atmospheric effects. The description of this work as potentially having a "delicate technique" might hint at a refined handling of the medium.

Without viewing a broader range of his works or accessing contemporary critical assessments, it is difficult to place his style definitively within the major artistic currents of his time. Italy saw the lingering influence of the Macchiaioli movement's plein-air realism, the rise of Divisionism with its scientific approach to color, and the emergence of Symbolism, followed by the revolutionary stirrings of Futurism early in the 20th century. Bentivoglio likely worked within the more established traditions of landscape and figurative painting, possibly influenced by regional Genoese artists or broader national trends towards realism and naturalism.

His consistent return to Ligurian subjects suggests a deep connection to his native environment, a common theme for many artists of the period who sought inspiration in their local surroundings. The titles Riviera ligure, Marina ligure, and Paesaggio dell'entroterra ligure all point to this regional focus. His work likely aimed to capture the specific character and beauty of this coastal and inland scenery.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

While the provided sources state there is no direct evidence of Cesare Bentivoglio collaborating with specific contemporary painters, his active period (roughly the 1890s through the 1940s) placed him amidst a vibrant Italian art scene. Understanding this context helps situate his likely artistic environment, even if his direct interactions remain unknown.

The late 19th century in Italy was marked by diverse artistic trends. The Macchiaioli, Tuscany's revolutionary plein-air painters like Giovanni Fattori and Telemaco Signorini, had already made their mark, emphasizing realism and capturing light through patches (macchie) of color. While their main impact was earlier, their influence on landscape painting persisted. Bentivoglio's focus on Ligurian landscapes places him within this broader Italian tradition of depicting regional scenery with naturalistic intent.

Simultaneously, Divisionism (or Pointillism as practiced in France) gained traction, particularly in Northern Italy. Artists like Giovanni Segantini, Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, Angelo Morbelli, and Gaetano Previati explored the optical mixing of colors by applying paint in small dots or strokes. Their subjects often ranged from Alpine landscapes (Segantini) to social realism (Pellizza, Morbelli) and Symbolist themes (Previati). While there's no indication Bentivoglio adopted a Divisionist technique, these artists were significant contemporaries shaping the national artistic dialogue.

Landscape painting remained a popular and evolving genre. Artists like Antonio Fontanesi had earlier brought influences from the Barbizon School to Italy. Later figures such as Mosè Bianchi, Filippo Carcano, and Leonardo Bazzaro continued to explore landscape and genre scenes with varying degrees of realism, Impressionist influence, and atmospheric sensitivity. The aforementioned Beppe Ciardi, though Venetian, was a noted painter of lagoons and coastal scenes, active during Bentivoglio's time, highlighting the continued interest in maritime and landscape subjects across Italy.

Genoa and Liguria had their own local artistic traditions and figures, though perhaps less internationally prominent than centers like Florence, Milan, or Venice. Artists like Plinio Nomellini, though associated with Divisionism and later based in Tuscany, spent time in Genoa and depicted Ligurian scenes. The artistic environment in Genoa would have included local academies, exhibitions, and circles of artists, providing a milieu within which Bentivoglio likely operated, exhibited, and perhaps found patrons. His work should be seen against this backdrop of evolving national styles and strong regional landscape traditions.

Legacy and Art Historical Placement

Cesare Bentivoglio (1868-1952) emerges from the available records as a competent and recognized Italian painter, primarily associated with the landscapes and seascapes of his native Liguria. His connection to the illustrious Bentivoglio family of Bologna adds a layer of historical resonance, though his own life appears to have been lived far from the centers of political power, focused instead on his artistic practice in Genoa.

His legacy is primarily preserved through the works that occasionally surface in the art market, such as Riviera ligure, Marina con velieri all'orizzonte, and Paesaggio dell'entroterra ligure. These pieces confirm his activity as a professional artist specializing in regional subjects, proficient in both oil and pastel techniques. The auction estimates suggest a moderate but respectable valuation for his work during the periods they were assessed.

Unlike his Renaissance ancestors, whose lives are extensively documented through chronicles, letters, and state papers detailing their political triumphs and tribulations, Cesare Bentivoglio the painter remains a more elusive figure. The sources consulted explicitly note the lack of recorded personal anecdotes, controversies, or detailed biographical information concerning him. He seems to have lived a life dedicated to his art, leaving behind canvases rather than political treaties or records of courtly intrigue.

This contrasts sharply with the historical figures who share his name. The consulted texts, for instance, mistakenly attribute discussions of controversies involving Renaissance figures like Giovanni II Bentivoglio (his conflicts with Cesare Borgia and Pope Julius II) or unrelated individuals like the poet Ercole Bentivoglio or the modern artist Mirella Bentivoglio to the painter Cesare Bentivoglio. This highlights the need for careful distinction: the painter Cesare Bentivoglio (1868-1952) appears to have had an uncontroversial career focused on art, distinct from the dramatic histories of other Bentivoglios.

In the broader sweep of art history, Cesare Bentivoglio can be placed among the many capable Italian artists working in the representational traditions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His focus on Ligurian landscapes connects him to a strong current of regional painting in Italy. While perhaps not a major innovator who drastically altered the course of art, his work contributed to the rich tapestry of Italian art during a period of significant social and cultural change, bridging the era of traditional academies and the dawn of modernism. His paintings offer glimpses into the Ligurian world as he saw it, rendered with professional skill and a clear affection for his native region. His name serves as a reminder of how history echoes down the centuries, linking a modern Genoese artist to the powerful Renaissance lords of Bologna.