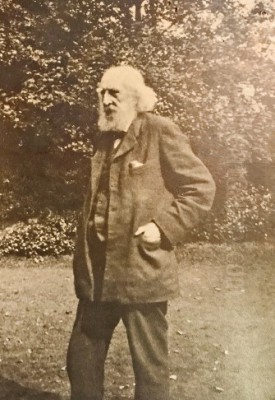

Charles Augustus Henry Lutyens (1829-1915) occupies a unique, if somewhat understated, position in the annals of British art history. Primarily remembered today as the father of the preeminent architect Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens, Charles himself was a man of diverse talents: a dedicated military officer and a painter of considerable skill, particularly noted for his depictions of animals. His life spanned a transformative period in British history and art, witnessing the zenith of Victorianism and the dawn of modernism. While not achieving the widespread fame of his son or some of his artistic contemporaries, his contributions to art and his influence within his own family are worthy of detailed exploration.

Early Life and Military Service

Born in Kensington, London, in 1829, Charles Augustus Henry Lutyens was destined for a life that would blend the discipline of military service with the creative pursuits of an artist. The London of his birth was a burgeoning metropolis, the heart of a vast empire, and a crucible of artistic and intellectual activity. His upbringing would have exposed him to the prevailing cultural currents of the early Victorian era.

In 1848, at the age of nineteen, Lutyens embarked on a military career, joining the 20th (East Devonshire) Regiment of Foot. This was a common path for young men of his social standing, offering structure, a sense of duty, and opportunities for travel and advancement. He served as a Captain, and his duties took him across the Atlantic to Montreal, Canada. Service in Canada during this period was significant, as Britain maintained a strong military presence in its North American colonies. His experiences there, the landscapes, and the way of life, may well have subtly influenced his later artistic sensibilities, particularly an appreciation for the natural world and perhaps the robust life associated with equestrian activities.

It was during his time in Canada, or shortly thereafter, that he met Mary Theresa Gallwey. She was the daughter of Michael Gallwey, an officer in the Royal Irish Constabulary, a force with a complex history in Ireland. The Gallwey family background, with its Irish roots and connections to service, would have resonated with Lutyens' own military life. Charles and Mary Theresa married in 1852. Their union was a prolific one, resulting in fourteen children, a testament to the large family sizes common in the Victorian era. Among these children was Edwin Landseer Lutyens, who would go on to become one of Britain's most celebrated architects. The naming of his son "Edwin Landseer" was a direct homage to his friend, the renowned animal painter Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, indicating Charles's early and deep connections to the art world.

Lutyens continued his military career, eventually rising to the rank of Major-General. This was a significant achievement, reflecting a long and dedicated service to the Crown. The life of a Victorian officer, even in peacetime, was demanding, requiring leadership, discipline, and often, postings in various parts of the Empire.

A Transition to Art

Upon his retirement from the military, Charles Augustus Henry Lutyens did not settle into quiet inactivity. Instead, he moved to London and dedicated himself more fully to his passion for art. This transition from a structured military life to the more introspective world of artistic creation is a fascinating aspect of his biography. It suggests a long-held interest that could finally be pursued without the constraints of a demanding military career.

He immersed himself in formal artistic study, enrolling in courses on art and sculpture. A particular area of focus for him was animal anatomy. This interest was not merely academic; it was foundational to his artistic practice. A deep understanding of the musculature, skeletal structure, and movement of animals is crucial for any artist wishing to depict them with accuracy and vitality. His dedication to this study underscores his serious approach to his second career as an painter. His military background, particularly if it involved cavalry or equestrian duties, would have given him ample opportunity to observe horses, which became a prominent subject in his work.

His studio practice would have been informed by the prevailing academic traditions of the time, which emphasized careful observation, skilled draughtsmanship, and a polished finish. London in the latter half of the 19th century was a vibrant artistic hub. The Royal Academy of Arts was the dominant institution, and its annual exhibitions were major social and cultural events. Artists like Lord Frederic Leighton, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and Sir John Everett Millais (a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood who later became President of the Royal Academy) were leading figures, and their work set a high standard for technical skill and narrative content.

Artistic Style and Notable Works

Charles Augustus Henry Lutyens developed a style that was well-suited to his chosen subjects. His paintings, particularly those of animals, are characterized by careful attention to detail, an understanding of form, and a sense of naturalism. Horses and lions were reportedly among his favorite subjects, animals that embody strength, grace, and a certain wild nobility.

While a comprehensive catalogue of his works is not widely available, several paintings have been attributed to him, reflecting his thematic interests. Among these, "The Gleaners" and "The Harnessing of the Black Horses" are titles that suggest a focus on rural life and equestrian subjects. "The Gleaners" would likely depict scenes of agricultural labor, a popular genre in Victorian art, often imbued with social commentary or a romanticized view of country life, as seen in the works of French artists like Jean-François Millet, whose influence was felt across Europe. "The Harnessing of the Black Horses" clearly points to his expertise in equine art, a tradition with a long and distinguished history in Britain, exemplified by artists such as George Stubbs in the previous century, and contemporaries like John Frederick Herring Sr. and Abraham Cooper.

Another work sometimes associated with his name is "Cherubs with Flower Garlands." If accurately attributed, this piece would indicate a broader thematic range, venturing into more decorative or allegorical subjects popular in Victorian art. The depiction of cherubic figures was common, often symbolizing innocence, love, or the divine.

It is important to note that some artworks with later creation dates, such as "The Angels of the Heavenly Host" (a mosaic dated 1963-1968) or "Before the Hunt" (dated 1998), have occasionally been anachronistically linked to Charles Augustus Henry Lutyens. Given his death in 1915, these attributions are clearly incorrect and likely refer to works by other artists, possibly descendants or individuals with similar names. His primary artistic output occurred in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His focus remained largely within the realm of representational art, typical of many Victorian painters who valued verisimilitude and skilled craftsmanship.

His interest in animal painting places him within a strong British tradition. Artists like Richard Ansdell, known for his depictions of animals and Scottish scenes, and Briton Rivière, who often painted animals in dramatic or historical contexts, were his contemporaries. The public had a strong appetite for animal painting, whether it was sporting art, depictions of domestic pets, or more exotic creatures.

Connections and the Artistic Milieu

Charles Augustus Henry Lutyens was well-connected within artistic circles, partly through his own endeavors and significantly through his son, Edwin. His friendship with Sir Edwin Henry Landseer is the most prominent direct connection. Landseer was a towering figure in Victorian art, a favorite of Queen Victoria, renowned for his sentimental and anthropomorphic depictions of animals, particularly stags, dogs, and horses. The fact that Charles named his son after Landseer speaks volumes about his admiration and personal relationship with the artist. They likely moved in similar social circles, and Landseer's studio in St John's Wood was a hub for artists and society figures. Lutyens himself resided for a time at 16 Onslow Square, an area popular with artists.

The late Victorian and Edwardian art world was a dynamic environment. While the Royal Academy upheld traditional values, new movements and groups were emerging. The Arts and Crafts Movement, championed by figures like William Morris and John Ruskin (whose writings profoundly influenced artistic thought), emphasized craftsmanship and a return to pre-industrial values. The Aesthetic Movement, with proponents like James McNeill Whistler, focused on "art for art's sake," prioritizing beauty and artistic sensibility over narrative or moral content. The New English Art Club was formed in 1886 as an alternative to the Royal Academy, attracting artists influenced by French Impressionism, such as Philip Wilson Steer and Walter Sickert.

While Charles Lutyens's own work seems to have remained within a more traditional vein, he would have been aware of these shifting artistic tides. His son, Edwin, certainly engaged with the Arts and Crafts ethos in his early architectural work, particularly through his fruitful collaboration with the garden designer and artist Gertrude Jekyll. Jekyll herself was a multifaceted artist, initially a painter before her eyesight led her to focus on garden design. Charles, as Edwin's father, would undoubtedly have known Jekyll and been familiar with their groundbreaking work that fused architecture and garden design into harmonious wholes.

Edwin Lutyens's circle also included other prominent artists. He collaborated with the architect Herbert Baker on the ambitious project of designing New Delhi, though their relationship was famously fraught with professional disagreements. Edwin was also friends with the painter William Nicholson, known for his sophisticated still lifes, portraits, and graphic work. While these connections are primarily through his son, they illustrate the rich artistic environment in which the Lutyens family moved. Charles may have encountered artists like Max Gill (MacDonald Gill), an artist and cartographer who undertook commissions for Edwin Lutyens, including decorative maps.

The Art Workers' Guild, founded in 1884, brought together architects, painters, sculptors, and craftsmen, aiming to break down the barriers between fine and applied arts. Figures like Walter Crane and W.R. Lethaby were instrumental in its formation. If Charles Lutyens or his son were connected to the Guild, it would have provided a forum for interaction with a wide range of creative individuals.

Anecdotes and Personal Character

While detailed personal anecdotes specifically about Charles Augustus Henry Lutyens are less documented than those of his famous son, some insights into the family character can be gleaned. The Lutyens family, by all accounts, was lively and creative. The decision to name his son after Landseer suggests a man who valued friendship and artistic achievement. Raising fourteen children would have required considerable fortitude and resourcefulness from both Charles and his wife, Mary Theresa.

Mary Theresa's Irish background and reported devout Evangelical faith would have added another dimension to the family's life. The Victorian era was a period of intense religious feeling and debate, and this would have shaped the household's moral and social outlook.

The anecdotes often attributed to "Lutyens" regarding a keen sense of humor, a childhood marked by illness that fostered a close bond with his mother, and an early, self-devised method of learning to draw using a piece of glass, soap, and a sharpened chalk, are more commonly associated with his son, Sir Edwin Lutyens. However, such traits often run in families, and it's plausible that Charles himself possessed a similar creative spark and perhaps a dry wit, common among military men. His dedication to learning animal anatomy in his retirement certainly points to a disciplined and curious mind.

His military service in Canada, followed by a career as a painter in London, suggests a man of adaptability and diverse interests. The transition from the structured hierarchy of the army to the more individualistic pursuit of art is significant. It speaks to a passion that was strong enough to define the later part of his life.

Legacy and Conclusion

Charles Augustus Henry Lutyens passed away in 1915, a year into the First World War, a conflict that would irrevocably change Britain and the world. His life had bridged the confident high Victorian era with the uncertainties of the early 20th century.

His most visible legacy is undoubtedly his son, Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens, whose architectural achievements are celebrated globally. Charles provided the environment and perhaps the genetic predisposition that nurtured his son's genius. The very act of naming him after Sir Edwin Henry Landseer was a clear indication of the artistic aspirations he held or admired.

As an artist in his own right, Charles Augustus Henry Lutyens contributed to the rich tapestry of Victorian animal painting. His work, characterized by anatomical accuracy and a sympathetic portrayal of his subjects, found a place within a popular and respected genre. While he may not have achieved the fame of Landseer or the revolutionary impact of the Impressionists or Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne or Vincent van Gogh (whose work was becoming known in Britain around the time of Lutyens's later career, notably through the 1910 "Manet and the Post-Impressionists" exhibition organized by Roger Fry), his dedication to his craft was evident.

He represents a particular type of Victorian gentleman: one who capably fulfilled his duties in a conventional profession like the military, while also cultivating a genuine talent and passion for the arts. His paintings of horses, lions, and potentially other subjects, offer a glimpse into the artistic sensibilities of a man who lived through a period of immense change. His life and work serve as a reminder that artistic endeavor can flourish alongside other demanding careers, and that the familial context, such as the one he provided for his gifted son, can be a powerful incubator for creative brilliance. Charles Augustus Henry Lutyens, officer and artist, remains a figure of interest, embodying the multifaceted nature of Victorian talent and the enduring appeal of animal art. His story is intertwined with the greater narrative of British art and the remarkable career of his son, ensuring his name a quiet but persistent place in cultural history.