Charles Brooking stands as one of the most gifted and influential marine painters Britain produced in the 18th century. Despite a tragically short life, spanning merely thirty-six years from 1723 to 1759, his work achieved a level of sensitivity, accuracy, and atmospheric truth that set a new standard for the genre in England. He possessed an innate understanding of the sea in its varied moods and an unparalleled ability to depict the complex structures and movements of ships with convincing realism. His legacy, though based on a relatively small body of work, profoundly shaped the direction of British marine art.

Early Life and Maritime Environment

Charles Brooking was born in Deptford or Greenwich, London, around 1723. This location was significant; situated on the River Thames, it was a hub of maritime activity, home to naval dockyards and the Royal Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich. It is believed his father, also possibly named Charles, worked as a painter and decorator at the Greenwich Hospital, a vast complex dedicated to naval pensioners. This familial connection likely provided the young Brooking with early exposure to ships, sailors, and the broader maritime world that would become the sole focus of his artistic career.

Records indicate that a Charles Brooking was listed as an apprentice at the Greenwich Hospital between 1732 and 1736. While direct confirmation is lacking, it is highly probable this was the future artist. Such an environment would have offered him intimate, firsthand knowledge of ship construction, rigging, and the daily life of a major naval center. This practical grounding, combined with a natural artistic talent, formed the bedrock of his later mastery in depicting nautical subjects. Unlike artists who approached marine themes from a purely landscape perspective, Brooking's work resonates with the authenticity of lived experience.

The Dutch Legacy and Brooking's Artistic Formation

The dominant influence on marine painting in Britain during the early 18th century was overwhelmingly Dutch. The arrival of Willem van de Velde the Elder (c. 1611–1693) and his son, Willem van de Velde the Younger (1633–1707), in England in 1672/73, under the patronage of King Charles II and later James II, established a powerful artistic dynasty. Their meticulous draughtsmanship, sophisticated understanding of light and water, and dramatic compositions became the benchmark against which subsequent marine artists were measured.

Brooking clearly absorbed the lessons of the Van de Veldes. His work echoes their careful attention to detail, particularly in the rendering of ships' hulls, sails, and intricate rigging. He adopted their compositional strategies, often employing low horizons to emphasize the vastness of the sky and sea. However, Brooking was no mere copyist. He infused the Dutch tradition with a distinctly English sensibility, characterized by a cooler palette, a softer handling of light, and a more nuanced observation of atmospheric effects specific to British waters.

While the Van de Veldes often depicted specific naval battles or ceremonial occasions, Brooking frequently focused on more general scenes of shipping in coastal waters, capturing the interplay of light, wind, and water with remarkable subtlety. His work represents a crucial transition, moving beyond the established Dutch formulas towards a more personal and atmospheric interpretation of the marine environment. He stands alongside artists like Peter Monamy (1681–1749), an older contemporary who also worked within the Dutch tradition but began to forge a more native style.

Hallmarks of Brooking's Style: Accuracy and Atmosphere

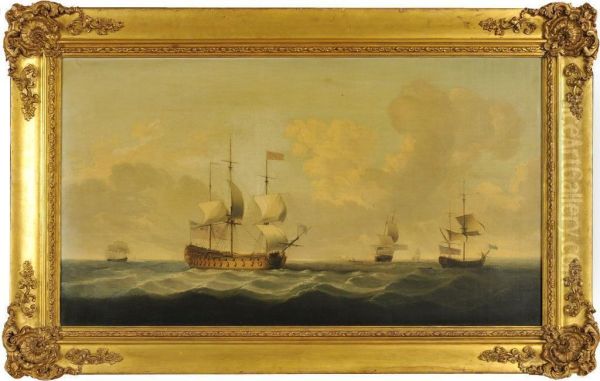

Brooking's paintings are celebrated for their exceptional accuracy. He possessed a profound knowledge of naval architecture and seamanship, evident in the precise rendering of different vessel types, from imposing warships to humble fishing boats. The set of sails, the tension in the rigging, and the way a ship sits in the water are all depicted with an expert eye. This technical veracity lends his work an air of undeniable authenticity, appreciated by sailors and landlubbers alike.

Beyond mere accuracy, Brooking excelled at capturing the intangible qualities of light and atmosphere. He was a master of depicting calm seas under hazy skies, the gentle swell of the water reflecting the soft light. Equally, he could convey the energy of a fresh breeze filling the sails, whipping up whitecaps on the waves, and scattering clouds across the sky. His ability to render the transparency of water and the subtle gradations of tone in the sky and sea was exceptional for his time.

His palette, often favouring cool blues, greys, and greens, perfectly captured the specific light conditions of the English Channel and North Sea. Unlike the warmer tones sometimes favoured by Dutch masters, Brooking's colours feel specific to the northern maritime environment. This sensitivity to atmosphere imbues his work with a poetic quality, elevating it beyond simple ship portraiture or topographical recording. He observed nature keenly and translated his observations into paint with lyrical grace.

Representative Works: Calm and Breeze

Brooking's oeuvre showcases his versatility in depicting various weather conditions. Among his most admired works are his calms. A Frigate and a Yacht becalmed in the Solent, for instance, exemplifies his skill in this area. The sea is rendered as a near-mirror, reflecting the idle vessels and the soft, luminous sky. The sails hang slack, and a profound sense of stillness pervades the scene. Yet, even in tranquility, Brooking's attention to detail remains sharp – the intricate carving on the yacht's stern, the reflections shimmering on the water's surface, are all meticulously observed.

In contrast, works like Merchant ships passing in the Channel demonstrate his ability to capture scenes of gentle activity under a light breeze. Here, the sails are beginning to fill, the ships lean slightly, and the water shows movement with small waves and ripples. The composition is balanced, the light clear, conveying a sense of routine maritime commerce. These paintings highlight Brooking's understanding of how wind affects both the sea and the vessels navigating it.

He often included smaller craft, like fishing boats or cutters, alongside larger ships, adding visual interest and scale. His depiction of these working vessels is just as careful and sympathetic as his portrayal of grander naval ships or merchantmen. This breadth of subject matter reflects the diverse maritime life he would have witnessed around the Thames estuary and the English coast.

The Foundling Hospital Commission: A Landmark Painting

A pivotal moment in Brooking's career, albeit one that brought him wider recognition perhaps too late, involved the Foundling Hospital in London. This charitable institution, established by Captain Thomas Coram for abandoned children, became an unlikely but important centre for the promotion of British art. Encouraged by William Hogarth (1697–1764), artists donated works to decorate the hospital's public rooms, effectively creating one of London's first public art galleries and fostering native talent.

Around 1754, Taylor White, the Treasurer of the Foundling Hospital and a keen observer, reportedly discovered Brooking working in relative obscurity for a picture dealer who was selling Brooking's works under his own name. Impressed by the artist's talent, White liberated him from this situation and secured him a commission from the hospital governors to paint a large sea-piece. The resulting work, often titled The Launch of a Ship or simply A Flagship Before the Wind, was a resounding success.

This impressive painting, depicting a British flagship firing a salute under a fresh breeze, showcased Brooking's full range of skills – accurate ship portraiture, dynamic composition, and masterful handling of sea and sky. Its exhibition at the Foundling Hospital brought Brooking to the attention of a wider, more influential audience. It remains one of his most celebrated works and a testament to the quality he could achieve when given a significant commission. Other artists who contributed to the Foundling Hospital included Hogarth himself, Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788), Richard Wilson (1714–1782), and Francis Hayman (1708–1776), placing Brooking in esteemed company.

Depicting Maritime Events and Activities

While many of Brooking's works depict general shipping scenes, he also occasionally tackled specific events or activities, often imbued with drama or historical significance. One such painting captures the Capture of the French ships 'Marquis d'Antin' and 'Louis Erasme' by the privateers 'Prince Frederick' and 'Duke', 10 July 1745. This event was notable because the captured French ships, returning from South America, carried a vast treasure in gold and silver. The painting depicts the naval action with Brooking's characteristic accuracy and attention to the conditions of sea and sky.

Brooking also ventured into depicting the harsh realities of Arctic whaling. Paintings titled Whalers in the Ice or similar show whaling ships navigating treacherous ice fields. These works contrast the stark, geometric forms of the icebergs with the vulnerability of the wooden ships. While often rendered with a sense of calm control, they hint at the dangers faced by seamen in these extreme environments, a theme that would later be explored more dramatically by Romantic painters like J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) in his own whaling scenes.

Some accounts mention a painting titled The Ice-Bound Ship or similar, depicting a vessel trapped after a storm, possibly in Arctic waters (references to the Antarctic in some sources are likely inaccurate for this period). Such works demonstrate Brooking's ability to evoke atmosphere and drama, portraying the power of nature and the perils of seafaring. These paintings, with their focus on specific maritime actions and environments, add another dimension to his oeuvre beyond tranquil coastal views.

Brooking in the Context of Mid-18th Century British Art

Charles Brooking worked during a vibrant period in British art. While portraiture, dominated by figures like Allan Ramsay (1713–1784) and the rising star Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), held the highest prestige, other genres were gaining ground. William Hogarth was pioneering modern moral subjects and conversation pieces. Landscape painting was evolving with artists like George Lambert (1700–1765) and Richard Wilson. Marine painting, though considered a lesser genre by some academic theorists, was popular, reflecting Britain's growing naval power and mercantile wealth.

Brooking's main contemporaries in marine art included Peter Monamy, who was senior to him, and Samuel Scott (c. 1702–1772). Scott, often called the "English Canaletto," specialized in detailed views of the Thames and London's waterfront, but also painted naval battles and coastal scenes, sometimes with a clarity and topographical precision that contrasts with Brooking's more atmospheric approach. Francis Swaine (c. 1725–1782) was another contemporary, whose style closely imitated Brooking's, sometimes leading to confusion in attribution. Richard Paton (1717–1791) was also active, known for his depictions of naval battles, often with dramatic lighting effects.

Brooking's dedication to marine subjects was almost total, distinguishing him from artists like Scott or Monamy who sometimes diversified. His focus allowed him to achieve a depth of understanding and refinement within the genre that was arguably unmatched in England during his lifetime. He successfully bridged the gap between the dominant Dutch influence and the emergence of a truly native British school of marine painting.

Influence and Legacy: Shaping the Future

Despite the recognition gained from the Foundling Hospital commission, Brooking's career was cut short by his death from consumption (tuberculosis) in 1759, at the age of just 36. He died in poverty, leaving a wife and children. His premature death meant his output was limited, and for a time, his work was relatively scarce and perhaps undervalued compared to his talent.

However, his influence was significant, primarily through Dominic Serres (1719–1793). Serres, a Gascon-born artist who settled in England after being captured at sea, became a close follower and possibly a pupil of Brooking. He inherited Brooking's meticulous style and understanding of ships, adapting it to depict the numerous naval actions of the Seven Years' War and the American War of Independence. Serres achieved considerable success, becoming Marine Painter to King George III and a founding member of the Royal Academy (established 1768). Through Serres, Brooking's stylistic legacy was transmitted and became foundational for the next generation of British marine painters.

Later artists like Nicholas Pocock (1740–1821) and Thomas Luny (1759–1837), who documented the naval conflicts of the Napoleonic Wars, owed a debt to the standards of accuracy and atmospheric rendering established by Brooking and continued by Serres. Even the great J.M.W. Turner, in his early sea pieces, shows an awareness of the 18th-century tradition that Brooking helped to shape, before revolutionizing the genre with his own unique vision.

Brooking's Works in Collections

Today, Charles Brooking's paintings are highly prized and can be found in major public collections, primarily in the United Kingdom and the United States. The National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London, holds the most significant collection of his works, reflecting his importance to Britain's naval heritage. The Tate Britain in London also possesses key examples, including coastal scenes and ship studies.

The Foundling Museum in London still proudly displays the large sea-piece commissioned from him in the 1750s. Other notable holdings can be found at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, which has a strong collection of British marine painting, and in various other national and regional museums. The relative scarcity of his works, due to his short life, makes each surviving painting a valuable testament to his skill.

His drawings and etchings, though less numerous than his oil paintings, also survive, showcasing his fine draughtsmanship and detailed observation. These works provide further insight into his working methods and his intimate knowledge of maritime subjects.

Conclusion: A Pivotal Figure in British Marine Art

Charles Brooking remains a figure of central importance in the history of British marine painting. Emerging from the shadow of the dominant Dutch school, he forged a style that was both technically brilliant and atmospherically sensitive, capturing the unique character of British waters and shipping. His deep understanding of nautical matters, combined with his artistic finesse, resulted in works of enduring beauty and accuracy.

His career was tragically brief, preventing him from achieving the widespread fame and financial security his talent deserved during his lifetime. Yet, the quality of his work spoke for itself, influencing key successors like Dominic Serres and helping to establish a strong native tradition of marine art in Britain. He stands as a master observer of the sea, whose paintings continue to fascinate viewers with their blend of precision, light, and poetic feeling, securing his reputation as one of England's greatest painters of the sea.