Charles Burton Barber stands as a significant figure in the annals of British Victorian art, celebrated primarily for his endearing and technically proficient depictions of children and their animal companions. His work, imbued with a gentle sentimentality and a keen observational skill, captured the hearts of his contemporaries, including the most discerning patron of all, Queen Victoria. Barber's paintings offer more than just charming scenes; they provide a window into the social mores, burgeoning affections for domestic pets, and the evolving perceptions of childhood that characterized the latter half of the 19th century.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

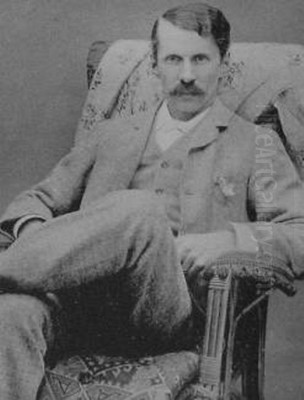

Born in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, in 1845, Charles Burton Barber's artistic inclinations manifested early. His formal training commenced at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London, which he entered at the age of 18. The Royal Academy was the crucible of British artistic talent, and Barber quickly proved his mettle. In 1864, a mere year or so into his studies, he was awarded a silver medal for drawing, a testament to his foundational skills and dedication. This early recognition would have undoubtedly bolstered his confidence and set the stage for a promising career.

The curriculum at the Royal Academy Schools during this period would have emphasized rigorous academic training, focusing on life drawing, anatomy, and the study of Old Masters. Artists like Sir Joshua Reynolds, the Academy's first president, had established a tradition of grand manner portraiture and historical painting, while later figures such as J.M.W. Turner and John Constable had revolutionized landscape art. Though Barber would carve his niche in a different genre, the discipline and technical grounding from the Academy were invaluable.

The Ascent of a Victorian Painter

Barber's career began to flourish in an era where genre painting – scenes of everyday life – was immensely popular. The Victorian public had a strong appetite for narratives, particularly those that evoked emotion, moral lessons, or the comforts of domesticity. Barber's chosen subjects, innocent children and loyal pets, resonated deeply with these sensibilities. He exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy from 1866 until 1893, a consistent presence that helped build his reputation.

His skill was not limited to sentimental subjects; he was also a capable portraitist. However, it was his unique ability to capture the subtle interactions and unspoken bonds between children and animals, especially dogs, that truly distinguished him. He possessed a profound understanding of animal anatomy and behavior, which allowed him to render his subjects with lifelike accuracy without sacrificing emotional warmth. This set him apart from many contemporaries who might have veered into overly saccharine or anthropomorphic representations.

Barber was also associated with the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, a significant institution dedicated to promoting the art of oil painting. He was, in fact, one of its earliest members, being elected in 1883. This affiliation further solidified his standing within the British art establishment. His works were also exhibited in other prominent venues, including the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool and the Manchester Art Gallery, indicating a broad appeal beyond the London art scene.

Themes and Subjects: Children and Their Animal Companions

The core of Charles Burton Barber's oeuvre lies in his exploration of the relationship between children and animals. His paintings are populated with rosy-cheeked children, often from affluent backgrounds, interacting tenderly with their beloved dogs, cats, or sometimes even rabbits. These scenes were not mere whimsical fancies; they tapped into a growing Victorian sentiment that cherished childhood innocence and the loyalty of domestic pets.

Dogs, in particular, feature prominently and are rendered with exceptional skill and empathy. From majestic St. Bernards and Newfoundlands to playful terriers and regal spaniels, Barber captured the distinct character of each breed. He understood that a dog's expression—a tilted head, a mournful gaze, an eager stance—could convey a wealth of emotion, often mirroring or complementing the sentiments of their human companions in the painting.

His depictions of children were equally nuanced. He portrayed them not as miniature adults, a common trope in earlier art, but as individuals with their own distinct personalities and emotional worlds. Whether it was a child sharing a secret with a pet, offering a morsel of food, or seeking comfort from a furry friend, Barber conveyed a sense of genuine affection and mutual understanding. This focus on the emotional lives of children and animals was a hallmark of his work, distinguishing him from artists like Walter Hunt, who also painted animals but often in more rustic or wild settings.

Royal Patronage: Painter to the Queen

Perhaps the most significant endorsement of Barber's talent came from Queen Victoria herself. The Queen was a noted animal lover, particularly fond of dogs, and had previously patronized Sir Edwin Landseer, the preeminent animal painter of the earlier Victorian era. After Landseer's death in 1873, a void was left for a painter who could capture the royal pets and children with similar skill and sensitivity. Charles Burton Barber rose to this esteemed position, becoming a favored court painter.

He received numerous commissions from Queen Victoria to paint her grandchildren, often accompanied by their pets. These royal commissions included portraits of the children of the Prince and Princess of Wales (later King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra). He also painted the Queen's favorite dogs, such as "Marco," a Pomeranian, and "Dash," a King Charles Spaniel. These works were not only personal mementos for the royal family but also served to further enhance Barber's public reputation. To be the Queen's chosen painter in this intimate capacity was a mark of high honor and trust.

His royal portraits, like his other works, were characterized by their charm and technical finesse. He managed to capture the likeness of his young royal sitters while imbuing the scenes with a sense of warmth and informality, despite the inherent formality of royal portraiture. This ability to balance decorum with genuine emotion was highly valued. His relationship with the royal household continued for many years, providing him with consistent work and unparalleled prestige.

Artistic Style and Technique

Charles Burton Barber was a meticulous craftsman. His style can be broadly categorized as academic realism, characterized by careful drawing, smooth brushwork, and a high degree of finish. He paid close attention to detail, whether it was the texture of an animal's fur, the fabric of a child's dress, or the subtle play of light on a surface. This precision contributed to the lifelike quality of his paintings.

While his compositions were often carefully arranged to tell a story or evoke a particular mood, they rarely felt staged or artificial. He had a knack for capturing seemingly spontaneous moments of interaction. His palette was typically warm and inviting, employing rich browns, soft creams, and gentle blues and pinks, which enhanced the sentimental appeal of his subjects. Unlike some of his contemporaries, such as Briton Rivière, whose animal paintings often carried a more dramatic or allegorical weight, Barber's focus remained on the gentle, everyday affections.

He was also known to work in a variety of formats, from finished oil paintings intended for exhibition to more informal sketches. Even in his sketches, his understanding of form and his ability to capture character were evident. He reportedly found the initial stages of a painting, the blank canvas, somewhat daunting, preferring the process once the composition began to take shape. This suggests a methodical artist who perhaps found more joy in the refinement and completion of a work than in the initial, more uncertain, creative burst.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several of Charles Burton Barber's paintings have become iconic representations of Victorian sentimental art.

Off to School (1883): This charming painting depicts a young girl, satchel on her arm, ready for school. She pauses at the door, her hand resting affectionately on the head of a large, gentle St. Bernard dog who seems reluctant to see her go. The scene beautifully encapsulates the bond between child and pet, as well as hinting at the increasing importance of education for girls in the Victorian era. The detail in the girl's attire and the dog's fur is exemplary.

A Special Plea (also known as In Disgrace or Out of Favour) (1893): This is one of Barber's most famous and emotionally resonant works. A young girl in a pristine white dress stands in a corner, clearly having been reprimanded. Her loyal terrier sits beside her, looking up with an expression of concern and sympathy, as if pleading her case. The tension in the scene, the child's dejection, and the dog's unwavering loyalty are masterfully conveyed. It’s a poignant illustration of the comfort animals can provide in moments of distress.

Marco: This portrait of Queen Victoria's beloved Pomeranian showcases Barber's skill in pure animal portraiture. The dog is depicted with an alert and intelligent expression, its fluffy coat rendered with exquisite detail. Such paintings were highly prized by the Queen and demonstrated Barber's ability to capture the individual personality of his animal sitters.

Favourite Dogs: As the title suggests, this work likely depicted a collection of cherished canine companions, possibly commissioned by an aristocratic or wealthy patron. Barber excelled at group portraits of animals, managing to give each dog its own distinct presence while creating a harmonious overall composition.

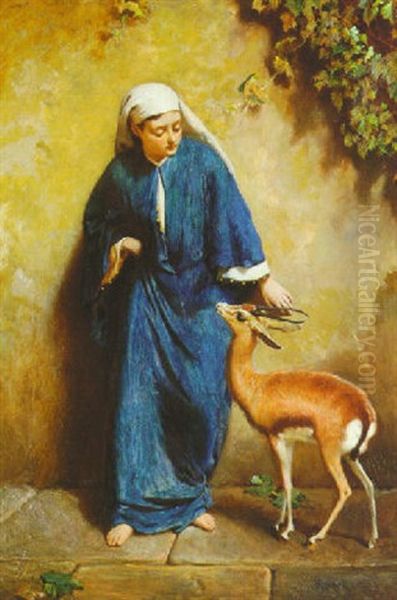

Sisters of Charity: While the title might suggest a religious theme, in Barber's context, it often referred to scenes where children and animals display kindness and compassion. This painting likely depicted children caring for animals or each other, reinforcing Victorian ideals of empathy and benevolence.

These works, and many others, were widely reproduced as prints and engravings, making Barber's art accessible to a much broader audience beyond those who could afford original oil paintings. This dissemination contributed significantly to his popularity and the enduring appeal of his imagery.

Contemporaries and Influences

Charles Burton Barber worked within a rich artistic milieu. His most obvious predecessor and influence in the realm of animal painting was Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873). Landseer's dramatic and often anthropomorphic depictions of animals, such as "The Monarch of the Glen," had set a high bar. Barber, while sharing Landseer's technical skill and love for animals, generally adopted a less grandiose and more intimately sentimental approach.

Other contemporary animal painters included Briton Rivière (1840-1920), known for his paintings of wild and domestic animals, often with narrative or symbolic content, and John Emms (1844-1912), who specialized in lively depictions of hounds and terriers. Walter Hunt (1861-1941) also painted charming farmyard scenes with animals and children, sharing some thematic similarities with Barber.

In the broader context of Victorian genre painting, artists like William Powell Frith (1819-1909), famous for his panoramic scenes of modern life like "Derby Day," and Luke Fildes (1843-1927), whose work "The Doctor" became an iconic image, were shaping the artistic landscape. While Barber's focus was narrower, his work shared the Victorian penchant for narrative and emotional engagement.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, with figures like John Everett Millais (1829-1896), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), and William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), had also made a significant impact with their emphasis on detail, vibrant color, and literary or symbolic themes. Though Barber's style was more traditionally academic, the Victorian era's general appreciation for meticulous rendering was a shared characteristic.

Barber was also friends with Harry Furniss (1854-1925), a renowned illustrator for Punch magazine. This connection highlights the interplay between fine art and illustration during the period. Another associate mentioned in some accounts is the landscape painter David Cox (1783-1859), though Cox belonged to an earlier generation. If they did paint together, it would likely have been early in Barber's career, or this may refer to a different Charles Barber, as Cox passed away when C.B. Barber was only 14. However, an appreciation for landscape, even as a backdrop, was common. Barber himself, though not primarily a landscape painter, was said to have an affection for Highland scenery, particularly red deer, which sometimes featured in his work.

The artist Frederick Morgan (1847/1856–1927) also specialized in idyllic scenes of childhood, often in rustic settings, and his work shares a similar sentimental appeal with Barber's. Later, Arthur Elsley (1860-1952) would continue in a similar vein, becoming highly popular for his depictions of children and pets in the Edwardian era, effectively inheriting Barber's mantle in this specific genre.

The Victorian Context: Art Reflecting Society

Barber's art is inextricably linked to the Victorian era's social and cultural landscape. The rise of the middle class created a new market for art that was relatable and reflected domestic values. The concept of childhood itself was undergoing a transformation, with a greater emphasis on innocence, play, and emotional development, a stark contrast to earlier periods where children were often viewed as miniature adults. Barber's tender portrayals of children resonated with these evolving attitudes.

Similarly, the Victorian era saw a surge in pet ownership and a growing sentimental attachment to domestic animals. Dogs, in particular, became symbols of loyalty and companionship. Organizations like the RSPCA (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals) were founded, reflecting an increasing concern for animal welfare. Barber's paintings, celebrating the bond between humans and animals, perfectly mirrored this societal trend. His work often subtly reinforced virtues such as kindness, loyalty, and compassion.

The educational themes in paintings like "Off to School" also touched upon contemporary concerns. The 1870 Education Act had made elementary education compulsory in England and Wales, and images of children engaged in learning or preparing for school were popular. Barber’s work, therefore, was not created in a vacuum but actively engaged with and reflected the values and preoccupations of his time.

Challenges, Quirks, and Artistic Process

Anecdotes suggest that Charles Burton Barber, despite his success, faced his own artistic anxieties. He was reportedly uncomfortable with the sight of a blank canvas, a feeling not uncommon among artists, and only truly began to enjoy the process of painting once a piece was well underway and nearing completion. This suggests a personality that perhaps thrived on order and the satisfaction of bringing a vision to full, detailed realization.

His meticulousness extended to the settings of his paintings. He often incorporated specific details of furniture, wallpaper, and interior décor, which not only added to the realism of his scenes but also provided valuable visual information about Victorian domestic interiors. This attention to detail, while time-consuming, was a key component of his appeal and the perceived authenticity of his work.

While he was not primarily a landscape painter, his occasional forays into depicting Highland scenery, especially with red deer, indicate an appreciation for nature beyond the domestic sphere. These works, though less common, would have showcased a different aspect of his skill, perhaps influenced by the romanticism associated with the Scottish Highlands, a favorite retreat of Queen Victoria.

Commercial Success and Reproductions

A significant aspect of Charles Burton Barber's fame and lasting impact was the widespread reproduction of his paintings. In an era before widespread color photography, engravings and prints were the primary means by which art reached a mass audience. Barber's work, with its clear narratives, charming subjects, and high degree of finish, lent itself exceptionally well to reproduction.

Publishers readily commissioned engravings of his most popular paintings, which were then sold in large numbers, adorning the walls of middle-class homes across Britain and beyond. This commercial success meant that images like "A Special Plea" became instantly recognizable and beloved. His paintings also found their way onto greeting cards, calendars, and other popular ephemera, further embedding his imagery into the popular culture of the time. While some artists might have disdained such commercialization, it played a crucial role in establishing Barber as a household name and ensuring the longevity of his most cherished compositions.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Charles Burton Barber died relatively young, in 1894, at the age of 49. However, in his comparatively short career, he created a body of work that left an indelible mark on Victorian art. His paintings continue to be admired for their technical skill, their heartfelt sentiment, and their charming portrayal of a bygone era.

His legacy can be seen in the continued popularity of his specific genre. Artists like Arthur Elsley successfully followed in his footsteps, catering to the public's enduring affection for scenes of childhood and animal companionship well into the 20th century. Today, Barber's original paintings are sought after by collectors and can command high prices at auction. They are held in private collections and public institutions, including the Royal Collection.

More broadly, Barber's work contributes to our understanding of Victorian culture. His paintings are valuable historical documents, offering insights into family life, social values, and the human-animal bond during a transformative period in British history. While art historical trends have often favored more avant-garde or overtly intellectual movements, the enduring appeal of Charles Burton Barber's art lies in its direct emotional honesty and its celebration of simple, universal affections. He remains a beloved figure, a master of capturing the tender moments that define the relationship between children and their cherished pets.

Conclusion

Charles Burton Barber was more than just a painter of cute children and dogs. He was a highly skilled artist who tapped into the zeitgeist of his era, creating works that resonated deeply with Victorian sensibilities and continue to charm audiences today. His association with the Royal Academy, his membership in the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, and, most notably, his patronage by Queen Victoria, all attest to his considerable talent and esteemed position within the 19th-century British art world. Through his meticulous technique and empathetic eye, Barber crafted a world of gentle sentiment and affectionate bonds, leaving behind a legacy of paintings that are both a delight to behold and a valuable reflection of Victorian life and values. His art reminds us of the enduring power of simple kindness and the profound connections we share with the animal kingdom.