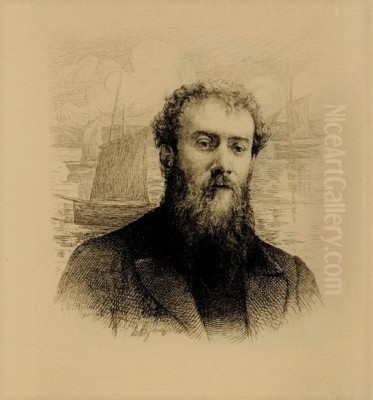

Charles Cottet stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in French art at the turn of the 20th century. Born in Le Puy-en-Velay on July 12, 1863, and passing away in Paris on September 25, 1925, Cottet carved a unique niche for himself within the diverse landscape of Post-Impressionism. He is most renowned for his powerful, often somber depictions of Brittany, its rugged landscapes, harsh seas, and the stoic lives of its inhabitants, particularly its fishermen and women. Rejecting the bright palettes favored by many contemporaries, Cottet became a leading figure of a group known as "La Bande Noire" (The Black Gang), celebrated for their darker tonalities and commitment to a form of expressive realism.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Charles Cottet's journey into the art world began not in his native Auvergne, but in Paris, the undisputed center of artistic innovation and training in the late 19th century. Seeking formal instruction, he enrolled in prestigious institutions that shaped generations of artists. He studied at the famed Académie Julian, a private art school known for its less rigid structure compared to the official École des Beaux-Arts, attracting a diverse international student body and fostering various artistic currents.

Cottet also attended the École des Beaux-Arts itself, gaining exposure to the more traditional, academic side of art education. Here, he benefited from the tutelage of influential figures. One notable teacher was Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, a highly respected painter known for his large-scale allegorical murals, characterized by simplified forms, muted colors, and a sense of calm monumentality. Though Cottet's path would diverge significantly from Puvis's style, the emphasis on strong composition and symbolic resonance may have left an impression.

Another significant influence during his formative years was Alfred Roll, a successful painter associated with Naturalism and official Salon art. Roll's work often depicted modern life with a certain robustness and realism, which might have resonated with Cottet's own developing interest in portraying contemporary life, albeit in a different regional setting and with a distinct emotional tone. Furthermore, the broader influence of Realism, particularly the legacy of Gustave Courbet with his unvarnished depictions of rural life and landscapes, provided a foundational context for Cottet's later focus on the raw realities of Breton existence.

His time at the Académie Julian also brought him into contact with students who would form the core of the Nabis group, such as Maurice Denis and Paul Sérusier. While Cottet did not become a Nabi himself, maintaining a more objective, observational stance compared to their subjective, decorative, and often spiritually infused symbolism, these early interactions placed him within the vibrant milieu of emerging Post-Impressionist ideas. This period of education provided Cottet with technical skills and exposed him to the competing artistic philosophies that defined the era, allowing him to forge his own distinct path.

The Revelation of Brittany

The pivotal moment in Charles Cottet's artistic career arrived in 1886 with his first visit to Brittany. This region, particularly the remote and weather-beaten island of Ouessant (Ushant) off the Finistère coast, captured his imagination profoundly and became the central subject of his life's work. Brittany, with its ancient traditions, distinct cultural identity, dramatic coastline, and the perilous lives of its seafaring communities, offered a powerful contrast to the urban sophistication of Paris.

Cottet was drawn to the raw authenticity he perceived in Breton life. He saw a people living in close communion with nature, their existence shaped by the rhythms of the sea, the demands of fishing, and the ever-present possibility of loss. He was particularly moved by the stoicism and resilience of the Breton people, especially the women who often waited anxiously for the return of their husbands and sons from the treacherous waters. This theme of waiting, mourning, and enduring hardship would become a recurring motif in his oeuvre.

He returned to Brittany year after year, immersing himself in the local culture and landscape. He didn't merely paint picturesque views; he sought to convey the very essence of the place – its atmosphere, its light (often gray and diffused), its deep-rooted customs, and the emotional weight carried by its inhabitants. His focus shifted from the anecdotal to the essential, capturing the timeless struggles and dignities of a community bound to the sea.

His depictions of Brittany ranged from expansive, moody seascapes under turbulent skies to intimate portrayals of village life, religious ceremonies like pardons, and poignant scenes of mourning. He painted the rugged cliffs, the humble cottages, the harbors filled with fishing boats, and the faces etched by sun, wind, and sorrow. Cottet became, in essence, the visual chronicler of "Le Pays de la Mer" – the Land of the Sea, as he titled one of his most famous works.

Artistic Style: The Power of Darkness

Charles Cottet's artistic style is immediately recognizable for its departure from the high-keyed colors and broken brushwork of Impressionism, as practiced by artists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and even from the brighter palettes of many fellow Post-Impressionists like Paul Gauguin (in his Tahitian period) or Vincent van Gogh. Cottet deliberately embraced a darker, more somber range of colors – deep blues, greens, grays, browns, and blacks dominate his canvases.

This was not simply a matter of accurately recording the often-overcast skies of Brittany; it was a conscious aesthetic choice aimed at conveying mood and emotional depth. His use of chiaroscuro, the dramatic interplay of light and shadow, often creates a sense of gravity, introspection, and sometimes melancholy. Figures are often solidly rendered, sometimes silhouetted against the sea or sky, emphasizing their connection to the elemental forces surrounding them. His brushwork, while painterly and expressive, generally defines form more clearly than that of the Impressionists, contributing to the feeling of solidity and permanence in his subjects.

His approach has often been described as a form of expressive realism or naturalism, deeply rooted in observation but infused with subjective feeling. There's an undeniable empathy in his portrayal of Breton life, a respect for the dignity of his subjects even when depicting their hardships. The influence of 17th-century Dutch masters, particularly marine painters known for their dramatic skies and seas, can be discerned in his atmospheric landscapes. Similarly, the precedent of French Realists like Courbet and Jean-François Millet, who elevated peasant life to a subject of serious art, informs Cottet's focus.

While sometimes associated with Symbolism due to the evocative mood of his work, Cottet generally avoided the overt allegory or mystical themes found in painters like Puvis de Chavannes or Gustave Moreau. His symbolism is more grounded, emerging naturally from the depicted reality – the vastness of the sea symbolizing fate, the dark clothing of the women signifying mourning and tradition, the rugged landscape reflecting the harshness of life. His darkness was not just tonal; it was emotional, capturing the solemn beauty and inherent tragedy he found in the Breton world.

La Bande Noire: A Counterpoint to Impressionism

Charles Cottet was not merely an individual artist working in isolation; he was the recognized leader of a group of like-minded painters known as "La Bande Noire" (The Black Gang or The Black Strip). This informal association, active primarily in the 1890s, shared Cottet's preference for a darker palette and a more solid, realist-inflected style, positioning themselves in contrast to the perceived dissolution of form and the emphasis on fleeting light effects found in Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism (Pointillism), championed by artists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac.

The name "Bande Noire" likely arose from their shared tonal preferences, distinguishing them from artists using brighter colors. Key members associated with Cottet in this group included Lucien Simon (who also frequently painted Breton themes), Edmond Aman-Jean (known for his elegant portraits and Symbolist-tinged works, though he shared the tonal restraint), André Dauchez (a skilled etcher and painter of Breton landscapes), René Ménard, and René-Xavier Prinet. While their individual styles varied, they were united by a commitment to strong composition, solid drawing, and an often somber or introspective mood.

La Bande Noire exhibited together and were seen by critics and the public as a distinct tendency within the diverse Parisian art scene. They represented a form of modern painting that valued tradition and direct observation, yet infused it with a contemporary sensibility and emotional depth. They admired artists like Courbet and were sometimes seen as inheritors of the Realist tradition, updated for the Post-Impressionist era. Their work found favor at the Salons, appealing to audiences who perhaps found the avant-garde experiments of Impressionism or the Nabis less accessible.

Cottet, as the most prominent figure associated with the group, embodied its core principles. His powerful Breton scenes, with their deep tones and empathetic portrayal of human endurance, became synonymous with the Bande Noire aesthetic. The group provided a supportive network for these artists and helped solidify their identity in the complex artistic landscape of fin-de-siècle Paris, offering a significant alternative to the dominant narratives of Impressionism and emergent Fauvism or Cubism.

Masterworks and Enduring Themes

Charles Cottet's reputation rests on a substantial body of work, with several pieces achieving iconic status. Perhaps his most celebrated work is the triptych titled "Au pays de la mer" (In the Land of the Sea), completed around 1898 and now housed in the Musée d'Orsay. This monumental work encapsulates his deep engagement with Breton maritime life and its inherent tragedies. The three panels depict distinct moments: "Ceux qui s'en vont" (Those Who Leave) shows fishermen departing, "Le Repas d'adieu" (The Farewell Meal) portrays a solemn family gathering before the men go to sea, and "Celles qui restent" (Those Who Stay) features the stoic, black-clad women gazing out at the ocean, embodying anxiety and loss. The triptych's somber palette, strong composition, and profound emotional resonance made it a landmark work.

Other significant paintings explore similar themes. "Vieille Femme de l'île de Sein" (Old Woman from the Île de Sein) is a powerful portrait capturing the weathered dignity of a Breton elder. "Petit village au pied de la falaise, île d'Ouessant" (Small Village at the Foot of the Cliff, Ouessant Island) exemplifies his ability to convey the atmosphere of the rugged coastline, dwarfing human habitation. Works like "Deuil marin" (Maritime Mourning) or scenes depicting funeral processions directly address the theme of loss that was so central to his Breton experience.

His seascapes are equally compelling, often focusing on the dramatic relationship between sea, sky, and land. "Soir Orageux, Ouessant" (Stormy Evening, Ouessant) captures the turbulent energy of the ocean, while other works might depict the calmer, more melancholic light of dusk settling over a harbor. He masterfully rendered the different moods of the sea and sky, using his characteristic dark tones to enhance the drama and atmosphere.

Beyond Brittany, his travels yielded notable works. His Venetian scenes, such as "View of Venice from the Sea," often retain a certain atmospheric quality, though sometimes incorporating slightly brighter light reflecting the different locale. His paintings from North Africa and Spain similarly show his ability to adapt his vision to new environments while maintaining his focus on essential forms and evocative mood. Throughout his diverse subjects, the themes of human endurance, the power of nature, and the weight of tradition remain central concerns.

Travels and Broadening Horizons

While Brittany remained the heartland of his artistic inspiration, Charles Cottet was also an avid traveler. These journeys took him beyond France, exposing him to different cultures, landscapes, and qualities of light, which subtly broadened his artistic practice without fundamentally altering his core vision. His travels provided new subject matter and occasionally led to shifts in his palette and approach.

Venice held a particular fascination for him, as it did for many artists. He painted numerous views of the city, capturing its unique interplay of water, architecture, and light. While some Venetian scenes incorporate brighter notes than his typical Breton works, they often retain a sense of atmosphere and sometimes a touch of melancholy, focusing perhaps on twilight hours or less conventional views, avoiding purely picturesque renditions. Works like "Girl in a Venetian Boat" show his continued interest in human subjects within their specific environment.

Cottet also journeyed to North Africa, visiting Egypt and Algeria. The intense light and distinct cultural milieu of these regions offered a stark contrast to the misty shores of Brittany. His works from this period sometimes feature a brighter palette and depict scenes of local life, markets, and landscapes. However, even in these sunnier climes, Cottet often sought out subjects or compositions that allowed for strong contrasts and a sense of enduring tradition, rather than adopting a purely Impressionistic response to the light.

Spain and the area around Lake Geneva in Switzerland were other destinations that provided inspiration. Each location offered unique visual stimuli, from the dramatic landscapes of Spain to the tranquil beauty of the Swiss lake. These travels demonstrate Cottet's curiosity and his desire to engage with diverse environments. Yet, his fundamental artistic temperament – his inclination towards gravity, strong forms, and emotional depth – remained consistent. The travels enriched his oeuvre, showcasing his versatility, but ultimately reinforced the unique power of his vision, which found its most profound expression in the rugged landscapes and resilient people of Brittany.

Cottet the Printmaker

Beyond his significant achievements as a painter, Charles Cottet was also a highly accomplished printmaker, particularly skilled in the technique of etching. His work in this medium parallels his paintings in terms of subject matter and mood, but also showcases his mastery of line, tone, and the specific expressive possibilities of printmaking. He produced a considerable number of etchings throughout his career, estimated at around sixty plates.

His etchings often revisit the themes that dominated his paintings: Breton landscapes, seascapes, and scenes of local life. He rendered the rugged cliffs, the turbulent sea, and the figures of fishermen and women with a powerful graphic sensibility. Etching allowed him to explore tonal contrasts with great subtlety and force, using dense networks of lines and carefully controlled biting of the plate to achieve deep, velvety blacks and dramatic highlights, perfectly suited to his somber aesthetic.

Works like "Pont en Royans" (showcasing an architectural subject, perhaps from his travels within France) or "Elderly Woman from Ouessant" demonstrate his skill in capturing texture, form, and character through line and tone alone. His prints were not mere reproductions of his paintings but independent works of art, exploring the unique potential of the etched line to convey emotion and atmosphere.

Initially working primarily in black and white, Cottet later explored color etching techniques, reflecting a broader trend among artists at the time who sought to expand the expressive range of printmaking. His commitment to printmaking underscores his dedication to craftsmanship and his exploration of different means to convey his artistic vision. His etchings were exhibited alongside his paintings and contributed significantly to his reputation, admired by fellow artists and collectors for their technical brilliance and emotional power. Figures like André Dauchez, also part of the Bande Noire, shared this dedication to etching, highlighting its importance within their circle.

Connections and Contemporaries

Charles Cottet navigated the complex art world of Paris, establishing relationships with a diverse range of fellow artists. His position as a leader of the Bande Noire placed him at the center of a circle that included Lucien Simon, André Dauchez, Edmond Aman-Jean, René Ménard, and René-Xavier Prinet. These artists shared stylistic affinities and often exhibited together, providing mutual support.

Beyond his immediate circle, Cottet maintained connections with other prominent figures. He reportedly had a close relationship with the sculptor Auguste Rodin. Despite the differences in their primary media and Rodin's more overtly dramatic and often sensual style, they likely shared a mutual respect rooted in their commitment to powerful figural representation and emotional expression. Their friendship highlights the interconnectedness of the Parisian art scene, where artists across different disciplines interacted.

His association with Félix Vallotton, a key member of the Nabis group, is also noteworthy. Vallotton, known for his stark woodcuts and paintings with flattened perspectives and sharp outlines, shared with Cottet an interest in strong composition and sometimes somber moods, though their stylistic means differed. Cottet's work was sometimes exhibited alongside the Nabis, and figures like Maurice Denis, another leading Nabi, were certainly aware of Cottet and the Bande Noire, even if their artistic philosophies diverged – the Nabis leaning more towards Symbolism, decoration, and subjective color, while Cottet remained closer to expressive realism.

In the context of Brittany, Cottet worked in parallel, though distinctly, from the Pont-Aven school artists like Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard. While they all drew inspiration from Brittany, Gauguin and Bernard pursued a more radical Synthetist style, emphasizing bold outlines, flat areas of color, and symbolic meaning, moving further from observed reality than Cottet typically did. Cottet's approach was less revolutionary but offered a powerful and enduring vision of the region. He also operated within the broader Salon system, exhibiting alongside more academic painters like his former teacher Alfred Roll or successful contemporaries like Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, who also depicted scenes of peasant life, albeit often with a more polished finish.

Later Years and Lasting Legacy

In the later part of his career, Charles Cottet continued to paint and exhibit, remaining faithful to the subjects and style that had established his reputation. He continued his travels, including trips that took him around the Mediterranean and back to his beloved Brittany. His work was widely recognized during his lifetime; he received accolades, including being made an Officer of the Legion of Honour, a significant mark of official recognition in France.

He maintained his position as a respected figure in the French art world, even as new avant-garde movements like Fauvism (with artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain) and Cubism (led by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque) dramatically shifted the landscape of modern art. Cottet represented a more conservative, though still distinctly modern, path, rooted in observation, tradition, and profound emotional engagement with his subject matter.

Charles Cottet passed away in Paris in 1925. His legacy is primarily tied to his powerful and evocative depictions of Brittany. He captured a specific time and place – the traditional life of Breton coastal communities at the turn of the century – with unparalleled empathy and atmospheric power. His work stands as a testament to a form of Post-Impressionism that valued substance, mood, and human dignity over purely formal experimentation or fleeting sensory effects.

While perhaps overshadowed in mainstream art history narratives by the more radical innovators of his time, Cottet's influence can be seen in subsequent generations of artists drawn to regional subjects, maritime themes, and expressive realism. His paintings and etchings continue to be admired for their technical mastery, their emotional depth, and their haunting portrayal of the "Land of the Sea." His work endures in major museum collections, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, offering a compelling vision of humanity confronting the forces of nature and tradition.

Conclusion: A Painter of Depth and Dignity

Charles Cottet occupies a unique and important place in the history of French art. As a leading figure of Post-Impressionism and the guiding spirit of La Bande Noire, he forged a distinctive path characterized by a somber palette, expressive realism, and a profound connection to his chosen subject: the land and people of Brittany. Rejecting the ephemeral brightness of Impressionism, he delved into the deeper, more enduring aspects of life, focusing on themes of labor, loss, tradition, and resilience.

His paintings of Breton fishermen and women, his dramatic seascapes, and his atmospheric landscapes are imbued with a powerful sense of mood and place. Through his mastery of tone and composition, he conveyed both the harshness and the solemn beauty of life on the edge of the sea. His extensive body of work, including his accomplished etchings, stands as a moving chronicle of a specific culture and a universal human condition. While contemporary with radical artistic revolutions, Cottet offered a compelling alternative, demonstrating that profound modernity could also be found in the empathetic observation of reality and the exploration of deep emotional currents. His art continues to resonate, reminding us of the power of painting to capture the soul of a place and the enduring dignity of the human spirit.