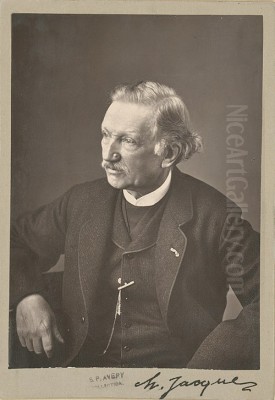

Charles-Émile Jacque stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. Born in Paris on May 23, 1813, and passing away in the same city on May 7, 1894, Jacque carved out a unique niche for himself as a painter and, perhaps even more notably, as a printmaker. He was a vital member of the Barbizon School, a movement that revolutionized landscape painting by emphasizing realism and direct observation of nature, moving away from the idealized scenes of Neoclassicism and the dramatic narratives of Romanticism. Jacque's particular focus on rural life, farm animals, and the quiet poetry of the French countryside earned him lasting recognition both in France and internationally.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

Jacque's path to becoming a full-time artist was not straightforward. His early years saw him employed in a law office, a profession far removed from the creative pursuits that would later define his life. He also undertook brief studies in engraving techniques, hinting at an early inclination towards the graphic arts. However, the structured world of law and formal training held less appeal than the burgeoning passion he felt for painting and drawing. This innate drive eventually led him to abandon his conventional career path and dedicate himself entirely to art.

His formative artistic experiences involved working as an illustrator and caricaturist. This practical training honed his skills in observation and draughtsmanship. In 1836, seeking to further develop his technical abilities, Jacque traveled to England. There, he immersed himself in the study of wood engraving, a popular medium for illustration at the time. This period abroad was crucial, broadening his technical repertoire and exposing him to different artistic currents. Upon returning to France, he contributed satirical drawings to popular journals like La Charivari, a publication known for its sharp social and political commentary, featuring artists like the renowned Honoré Daumier. This work, while commercial, provided invaluable experience in capturing character and narrative within visual art.

The Emergence of a Master Etcher

While illustration provided a foundation, the 1840s marked a significant shift in Jacque's artistic focus towards etching. He became deeply interested in this intaglio printmaking technique, which had fallen somewhat out of favor among fine artists since its golden age in the 17th century. Jacque was instrumental in the revival of etching as a serious artistic medium in 19th-century France. He drew profound inspiration from the Dutch Masters of the 17th century, particularly the unparalleled genius of Rembrandt van Rijn, whose mastery of light, shadow, and psychological depth in etching remained a benchmark. He also studied the works of Dutch landscape and animal painters, admiring their realistic depiction of rural life.

Jacque quickly gained proficiency and developed a distinctive style in etching, characterized by rich tonal variations and expressive line work. He wasn't merely imitating the old masters; he adapted the technique to his own sensibilities and subjects. His commitment to the medium was recognized when he first exhibited both etchings and paintings at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1844. This marked his official entry into the established art world. His prints, often depicting rustic scenes, animals, and landscapes, were well-received, and he began to build a reputation as a leading figure in the burgeoning etching revival, alongside contemporaries like Félix Bracquemond and Félix Buhot, who also championed the medium. He collaborated with Louis Marvy on publishing series of etchings, further promoting the art form.

The Move to Barbizon: A Defining Moment

A pivotal event occurred in 1849. Fleeing a severe cholera epidemic that swept through Paris, Jacque, along with his close friend and fellow artist Jean-François Millet, sought refuge in the small village of Barbizon. Located on the edge of the vast Forest of Fontainebleau, south of Paris, Barbizon was already attracting artists drawn to its unspoiled natural beauty and tranquil rural atmosphere. This move proved to be transformative for Jacque's art and life.

Settling in Barbizon, Jacque found himself at the heart of what would become known as the Barbizon School. This informal group of artists, including figures like Théodore Rousseau, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Constant Troyon, Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, and Jules Dupré, shared a common desire to paint landscapes and scenes of rural life with greater realism and fidelity to nature. They often worked outdoors (en plein air), directly observing the effects of light and atmosphere, a practice that would later influence the Impressionists. Jacque fully embraced the spirit of Barbizon, finding endless inspiration in the surrounding forests, fields, farms, and the lives of the local peasantry.

Capturing the Soul of the Countryside: Themes and Style

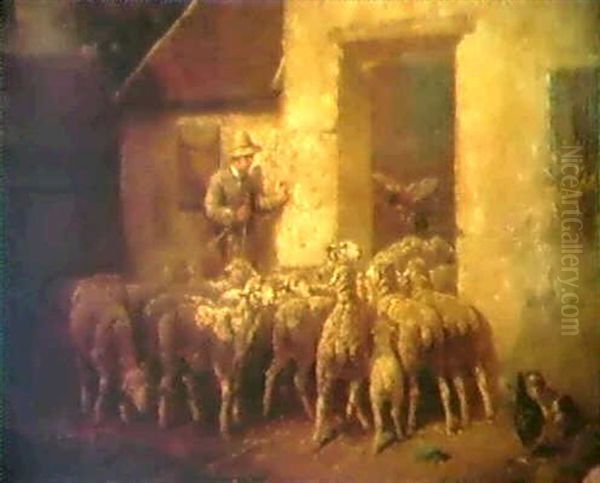

In Barbizon, Jacque's art truly flourished. He dedicated himself almost entirely to depicting the rustic world around him. While he painted landscapes, his most characteristic and celebrated subjects were scenes of farm life and, especially, animals. Sheep became a recurring and iconic motif in his work, often shown grazing peacefully in fields, huddled in barns, or being guided by shepherds. He rendered them with remarkable sensitivity and anatomical accuracy, capturing not just their appearance but also their characteristic movements and behaviours. Works like The Shepherdess and The Return of the Flock exemplify this focus, showcasing his ability to create harmonious compositions imbued with a sense of pastoral calm.

His fascination with animals extended beyond sheep to include pigs, poultry, and cattle. His painting Herd of Pigs is a notable example of his skill in portraying less conventionally 'picturesque' farm animals with dignity and realism. His interest was not merely artistic; Jacque was genuinely knowledgeable about animal husbandry. He even authored and illustrated a book titled Le Poulailler (The Henhouse), a practical guide to raising poultry, and wrote articles detailing his experiences with chicken farming in Barbizon. This deep, practical understanding informed his art, lending it an authenticity that resonated with viewers.

Jacque's style during his Barbizon period is characterized by naturalism. He employed fine, detailed brushwork, particularly in his earlier works, and demonstrated a masterful handling of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), often reminiscent of the Dutch Masters he admired. His compositions are typically well-balanced, conveying a sense of order and tranquility, even within humble farmyard settings. He captured the textures of wool, straw, earth, and bark with convincing realism, immersing the viewer in the tangible reality of the rural environment. While Millet often focused on the heroic struggle and quiet dignity of peasant labor, Jacque's focus was frequently more on the animals themselves and their integration within the landscape, presenting a slightly less monumental, though equally sincere, vision of country life.

Versatility and Recognition

Charles-Émile Jacque was a remarkably versatile artist. While best known for his paintings and etchings, his creative output encompassed a broader range of media. His early work in wood engraving and caricature has already been noted. Throughout his career, he also experimented with sculpture and lithography, demonstrating a restless curiosity and technical facility across different disciplines. This multifaceted approach enriched his artistic practice and contributed to his unique standing among his contemporaries.

His dedication and talent did not go unnoticed. Jacque achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. He was a regular exhibitor at the Paris Salon, where he won several medals over the years, attesting to the consistent quality and appeal of his work. His 1861 Salon entry, Landscape with Flock of Sheep, was particularly praised for its realism and technical skill. A significant honour was bestowed upon him in 1867 when he was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, France's highest order of merit. Further acclaim came in 1889 when he was awarded a Gold Medal at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris, cementing his reputation on an international stage. His work found appreciative audiences not only in France but also across Europe and notably in the United States, where Barbizon paintings were highly sought after by collectors.

Despite his professional success, Jacque's later life was marked by personal tragedy. His son, Lucien, was executed in 1871 during the brutal government suppression of the Paris Commune. This devastating event undoubtedly cast a shadow over the artist, yet he continued to work prolifically, finding solace and purpose in his art until his death in 1894.

Jacque and His Contemporaries: A Network of Influence

Jacque's career unfolded within a vibrant and transformative period in French art. His closest artistic relationship was undoubtedly with Jean-François Millet. Their shared move to Barbizon and their mutual interest in rural themes forged a strong bond, though their artistic temperaments differed slightly. Jacque was also a central figure within the broader Barbizon School, interacting regularly with its leading lights: Théodore Rousseau, the group's unofficial leader known for his dramatic forest scenes; Constant Troyon, another celebrated animal painter; Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, known for his richly textured forest interiors and mythological figures; Jules Dupré, who painted powerful landscapes and marine scenes; and Charles-François Daubigny, noted for his tranquil river landscapes often painted from his studio boat.

Beyond the Barbizon circle, Jacque's work connects to the wider Realist movement, spearheaded by Gustave Courbet, which challenged academic conventions by depicting ordinary life and unidealized subjects. Jacque's commitment to portraying the rustic world honestly aligns him with this broader trend. Furthermore, his pioneering work in etching connected him with other printmakers like Félix Bracquemond and Félix Buhot. His deep admiration for Rembrandt and other Dutch Golden Age painters like Paulus Potter or Aelbert Cuyp demonstrates his engagement with art history.

The Barbizon School, including Jacque's contributions, played a crucial role in paving the way for Impressionism. Artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley looked closely at the Barbizon painters' emphasis on capturing the effects of light and atmosphere and their practice of painting outdoors. While Jacque himself did not adopt the Impressionist technique, his dedication to observing and rendering nature directly was part of the evolutionary process that led to the later movement.

Artistic Legacy and Historical Significance

Charles-Émile Jacque's legacy rests on several key contributions. He was a cornerstone of the Barbizon School, helping to define its focus on realistic depictions of landscape and rural life. His paintings, particularly his sensitive and knowledgeable portrayals of animals, earned him the nickname "Le Raphaël des cochons" (The Raphael of pigs), a somewhat backhanded compliment that nevertheless acknowledged his supreme skill in this genre. His work captured a specific aspect of 19th-century French culture – a growing appreciation for the countryside and traditional ways of life, sometimes termed the "Renaissance Naturelle," as industrialization began to transform society.

Equally important was his role in the revival of etching. At a time when the medium was largely relegated to reproductive work, Jacque championed its potential for original artistic expression. He produced hundreds of etchings throughout his career, demonstrating the medium's versatility and influencing subsequent generations of printmakers. His technical mastery and artistic vision helped restore etching to a position of prominence in French art.

His influence extended through his family as well; his sons, Émile Jacque (1848–1912) and Frédéric Jacque (1859–1931), also became painters and engravers, continuing the family's artistic tradition. Today, Charles-Émile Jacque's works are held in major museums around the world, including the Louvre and Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery in London, and many others.

Conclusion

Charles-Émile Jacque was more than just a painter of sheep. He was a versatile, dedicated, and influential artist who made significant contributions to both painting and printmaking in 19th-century France. As a key member of the Barbizon School, he helped shift the focus of landscape art towards realism and the direct observation of nature. His intimate and knowledgeable depictions of rural life and animals remain distinctive and highly regarded. Simultaneously, his pioneering efforts in etching helped revitalize the medium, securing its place as a vital form of artistic expression. Through his prolific output and unwavering commitment to his vision, Jacque captured the quiet beauty and enduring spirit of the French countryside, leaving a rich and lasting legacy in the history of art.