Charles Jervas stands as a notable, if sometimes debated, figure in the landscape of early 18th-century British and Irish art. Born around 1675 and passing away in 1739, he navigated the worlds of portrait painting, literary translation, and art collecting with considerable social success, even if critical appraisal of his artistic output has varied over the centuries. His career reflects the artistic tastes, social connections, and cultural exchanges of the Augustan age in Britain.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Charles Jervas entered the world in Clonlisk, County Offaly (then known as King's County), Ireland, around 1675. He was the son of John Jervas and Elizabeth Johnson. While details of his earliest years in Ireland remain somewhat scarce, it is known that he relocated to England as a young man, seeking to establish himself in the burgeoning London art scene. This move proved pivotal for his future career trajectory.

His formal artistic training began in earnest when he became an apprentice, or at least a pupil, in the studio of Sir Godfrey Kneller. Kneller, a German-born painter who had dominated English portraiture since the late 17th century, was the leading court painter of his time, succeeding Sir Peter Lely. Working under Kneller provided Jervas with invaluable exposure to the techniques, styles, and business practices necessary for a successful portraitist catering to the aristocracy and gentry. Kneller's studio was a veritable factory of portraits, known for its efficiency and a certain Baroque flair that defined the era's official likenesses.

Seeking to further refine his skills and broaden his artistic horizons, Jervas, like many aspiring artists of his generation, embarked on a period of study in Italy. He spent time in Rome, the epicenter of classical tradition and Baroque innovation. There, he immersed himself in the study of the Old Masters and contemporary Italian painters. Sources suggest he particularly admired and studied the works of artists like Carlo Maratti, a leading painter in late 17th-century Rome, and Guido Reni, a Bolognese master whose elegant, classical style left a discernible, though sometimes criticized, mark on Jervas's own subsequent work. This period abroad was crucial for absorbing Continental artistic trends and building a collection of drawings and potentially paintings.

Ascent to Principal Painter

Upon returning to England from Italy, Jervas set about establishing his own practice. His connections, likely cultivated both before and during his time abroad, began to pay dividends. He moved within influential circles, associating with prominent figures who could offer patronage and support. His Irish background, combined with his training under the preeminent Kneller and his Continental experience, made him a viable contender in the competitive London art market.

A significant turning point in Jervas's career arrived in 1723. Following the death of his former master, Sir Godfrey Kneller, Jervas was appointed to the prestigious position of Principal Painter to King George I. This was the highest official artistic post in the kingdom, cementing his status at the forefront of the profession. He continued in this role under King George II after the succession in 1727, painting numerous portraits for the royal court.

His success was not solely reliant on royal favor. Jervas cultivated strong friendships within the era's vibrant literary and intellectual circles. He became particularly close with the poet Alexander Pope and the satirist Jonathan Swift. His London residence, located in Cleveland Court, St James's, reportedly became a gathering place for these and other wits. Pope even took painting lessons from Jervas, and their friendship is immortalized in Pope's epistle addressed to the painter. These connections undoubtedly enhanced Jervas's social standing and likely brought him numerous commissions, although some critics later suggested his fame owed more to his associations than to his intrinsic artistic merit.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Criticism

Jervas's painting style is often characterized as being heavily influenced by his training and studies, particularly the work of Kneller and the Italian masters he encountered in Rome. His portraits generally adhere to the conventions of late Baroque and early Rococo court portraiture, aiming for elegance and a certain idealized representation of the sitter. However, his work has frequently drawn criticism, both from contemporaries and later art historians.

A recurring critique, notably voiced by the engraver and chronicler George Vertue, was that Jervas's style lacked vivacity and naturalness. Vertue commented that Jervas seemed to imitate the faults of painters like Carlo Maratti without capturing their strengths. His reliance on the style of Guido Reni was also noted, sometimes negatively, suggesting it led to a certain stiffness or artificiality, particularly in the rendering of flesh tones and expressions. Some accounts describe his female portraits as lacking natural colour and vitality, appearing somewhat pale or doll-like.

Despite these criticisms, Jervas developed recognizable technical traits. His drawings, often executed in chalks, show a preference for black and red, sometimes accented with blue. He employed a soft, limited palette and utilized stumping – blending the chalk with a rolled paper or leather tool – to achieve smooth tonal transitions and model forms. This technique, while not unique, was perhaps less common than linear approaches among his contemporaries and contributed to the specific look of his preparatory studies and finished drawings.

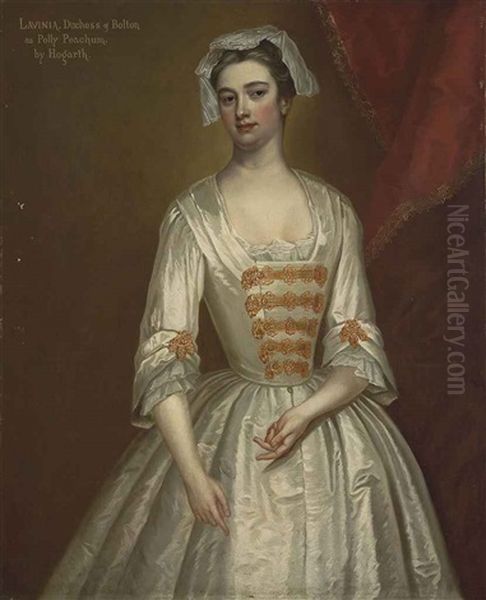

Interestingly, some analysis suggests a deliberate difference in his approach to male and female sitters. While his male portraits might strive for a degree of individual character (within the bounds of convention), his female portraits were sometimes seen as prioritizing a generic "recognizability" or fashionable ideal over capturing unique personality. This approach, while potentially sacrificing realism, might have served to align the female image with contemporary notions of decorum and public presentation, linking the sitter's authority visually to established social codes, as one source suggests. His style can be contrasted with the burgeoning, more robust realism and satirical edge found in the work of his slightly younger contemporary, William Hogarth.

Notable Works and Sitters

Given his position as Principal Painter and his connections within London's elite circles, Charles Jervas produced a significant number of portraits during his career. His most famous sitters reflect his close ties to the literary world. Portraits of Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift are among his best-known works. The portrait of Pope, dating from around 1713-1715, captures the poet with a thoughtful, intense gaze, reflecting the intellectual milieu they both inhabited. He likely painted Swift on multiple occasions, documenting the appearance of the celebrated Dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin.

His royal commissions included portraits of King George I and King George II, as well as other members of the royal family and court officials. These works would have followed the established protocols for state portraiture, emphasizing status and authority through pose, costume, and setting. While perhaps less dynamic than portraits by artists like his predecessor Kneller or visiting Continental painters like Jean-Baptiste van Loo, who arrived in London towards the end of Jervas's life, these royal portraits fulfilled their official function.

Regarding specific works, one source initially mentioned a portrait of Pope Clement XIII held at the National Portrait Gallery in London. However, the same source material later clarifies this attribution, correctly noting that the prominent portrait of Clement XIII is, in fact, by the German neoclassical painter Anton Raphael Mengs. This correction highlights the occasional confusion in attributions from this period. Jervas's documented works are primarily portraits of British and Irish aristocracy, gentry, and intellectuals.

Examples of Jervas's work can be found today in various collections. The provided information specifically mentions holdings at:

Castle Ward, County Down (National Trust), holding multiple works.

Wrest Park, Bedfordshire (English Heritage).

Audley End House, Essex (English Heritage).

The National Portrait Gallery, London, holds portraits associated with Jervas, particularly of his famous literary friends like Pope and Swift.

His contemporaries in the British portrait market included figures like the Swedish-born Michael Dahl, a significant rival to Kneller, and later arrivals like Hans Hysing, another Swede who gained popularity. The artistic landscape was competitive, featuring both native-born talents like Sir James Thornhill (more known for history painting) and established foreign artists.

Jervas the Translator: The 'Jarvis' Don Quixote

Beyond his activities as a painter and collector, Charles Jervas pursued literary interests, culminating in a significant translation project. He undertook the task of translating Miguel de Cervantes's masterpiece, Don Quixote, from Spanish into English. This was a considerable undertaking, reflecting Jervas's linguistic abilities and his engagement with Continental literature.

The translation was published posthumously in 1742, three years after Jervas's death. Due to a printer's error on the title page, his name was misspelled as "Jarvis." Consequently, this version became widely known as the "Jarvis translation." For many years, it was highly regarded, often considered the most faithful and accurate English rendering of Cervantes's text available up to that point. It aimed for a closer adherence to the original Spanish than some previous, more freely adapted translations.

However, despite its reputation for accuracy, the "Jarvis translation" also faced criticism, particularly regarding its style. Commentators noted that it could be somewhat stiff, literal, and lacking in the humour and vivacity that characterize Cervantes's original prose. While valuable for its fidelity, it perhaps failed to fully capture the spirit and comedic genius of the novel for English readers. Nevertheless, its publication was a significant event, contributing to the ongoing reception and appreciation of Don Quixote in the English-speaking world, and it remained an important version for decades.

Art Collection and Influence

Charles Jervas was not only a creator of art but also an avid collector. During his time in Italy and throughout his career, he acquired a collection of paintings and drawings, particularly favouring works by Italian masters whose styles he admired or sought to emulate. Art collecting was a common pursuit among successful artists and gentlemen of the period, serving as a mark of taste, a source of study, and potentially a financial investment. His collection likely included works attributed to artists like Guido Reni and Carlo Maratti, whose influence on his own painting is noted.

The dispersal of Jervas's collection after his death would have contributed to the circulation of Old Master works and copies within Britain. More significantly, the source material suggests that Jervas's own work and his collection had a "profound influence" on the development of portraiture styles, not only in his native Ireland but also in the American colonies.

While the exact mechanisms of this influence require detailed study, it's plausible that copies of his portraits, or works by artists trained or influenced by him, found their way across the Atlantic. The relatively formal, elegant style of Jervas, derived from the Kneller school but with its own idiosyncrasies, might have appealed to the elites in colonial centers like Boston, Philadelphia, or Charleston, who often looked to London for cultural cues. Artists active in the colonies during the mid-18th century, such as the Scottish-born John Smibert (who arrived in 1728) or the native-born Robert Feke, were developing their own styles but were certainly aware of prevailing British trends, which Jervas, as Principal Painter, represented.

Contemporary Connections and Social Standing

Jervas's career success was significantly bolstered by his network of connections. Beyond his famous friendships with Pope and Swift, the source material highlights relationships with other important figures who provided financial and social support, particularly in his early career. These included individuals like John Ellis, George Clark(e) (a notable politician and architect), Isaac Pereira (likely part of a prominent Sephardic merchant family), and William Digby, 5th Baron Digby, an Irish peer. These connections facilitated patronage, provided access to markets, and helped establish his reputation.

His time spent abroad also involved networking. While in Paris, he maintained correspondence with figures like Jonathan Hough and even produced satirical drawings, some of which are now housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. This indicates an engagement with different artistic forms and social commentary beyond formal portraiture.

His role as painting instructor to the King (George I) at St James's Palace further underscores his high standing at court. His home was not just a residence but a social hub, frequented by the leading literary lights of the day, making him a figure mentioned within the literature and correspondence of the period. This social integration was a key aspect of his professional life, distinguishing him perhaps as much as his artistic output.

Historical Reputation and Critical Legacy

The historical assessment of Charles Jervas remains somewhat complex and divided. On the one hand, he achieved considerable professional success, reaching the pinnacle of his profession as Principal Painter to two monarchs and enjoying the friendship and respect of major literary figures like Pope and Swift. His translation of Don Quixote was also a notable achievement, valued for its accuracy for a long period.

On the other hand, his artistic reputation has suffered, particularly when judged against the highest standards of portraiture. The criticisms voiced by George Vertue – regarding a lack of life, poor quality, and derivative style – have echoed through subsequent art historical accounts. Vertue felt Jervas was overrated in his own time, possibly due to his connections and self-promotion, and predicted that later generations would hold little interest in his work. To some extent, Vertue's prediction held true, as Jervas has often been overshadowed by his master, Kneller, and by the generation of painters who followed, such as Hogarth, Allan Ramsay, and Sir Joshua Reynolds, who brought new vitality and psychological depth to British portraiture.

Some sources suggest his talent might have appeared "mediocre" partly because he operated in an era rich with skilled painters, making it harder to stand out purely on merit. His success, therefore, is seen as a product of his training, his advantageous social connections, and perhaps a degree of good fortune in securing the royal appointment after Kneller's death. The criticism that his work could be visually "awkward" or lacked naturalism persists.

Conclusion

Charles Jervas occupies a significant, if contested, place in early Georgian art and culture. An Irishman who rose to become Principal Painter to the British monarchy, he was deeply embedded in the social and intellectual life of Augustan London. His friendships with Pope and Swift, his translation of Don Quixote, and his role as an art collector add dimensions to his career beyond the canvas.

While his portraiture has often been criticized for lacking the brilliance or naturalism of other masters, and his fame perhaps amplified by his associations, his work remains an important document of his time. His paintings provide likenesses of key figures, reflect the prevailing tastes in courtly and aristocratic portraiture, and demonstrate specific technical approaches. His influence, particularly claimed for Ireland and colonial America, suggests his style had a reach beyond London. Despite the reservations expressed by critics like Vertue, Jervas's multifaceted career – as painter, royal appointee, translator, collector, and friend to the wits – ensures his continued relevance for understanding the artistic and cultural landscape of early 18th-century Britain. He remains a figure whose success and artistic output invite ongoing study and re-evaluation.