Christophe-Ludwig Agricola (1667-1719) stands as a fascinating, if somewhat enigmatic, figure in the landscape of German Baroque art. A painter and etcher renowned for his evocative depictions of nature, particularly his skill in capturing transient atmospheric effects, Agricola carved a distinct niche for himself. His work, often characterized as an early manifestation of Baroque Romanticism within German painting, reflects a deep engagement with the natural world, influenced by his extensive travels and his keen observation of light and climate. Though details of his personal life and formal training remain relatively scarce, his artistic legacy endures in collections across Europe, testament to a talent that, while perhaps not as widely celebrated as some of his contemporaries, contributed significantly to the development of landscape painting.

Early Life and Self-Driven Artistry

Born in Regensburg, a historic city in Bavaria, Germany, in 1667, Christophe-Ludwig Agricola also passed away in his city of birth in 1719. The environment of Regensburg, with its rich medieval architecture and its position on the Danube River, may have offered early visual stimuli for the budding artist. However, specific details about his formative years and initial artistic instruction are sparse. It is widely believed that Agricola was largely self-taught, a remarkable feat given the technical proficiency evident in his mature works. In an era where apprenticeship under an established master was the conventional path to an artistic career, Agricola's independent development speaks to a strong personal drive and an innate sensibility for the visual arts.

His artistic endeavors appear to have gained momentum in Augsburg, another prominent city in Bavaria, known for its vibrant arts scene and its role as a center for printing and engraving. This environment would have provided Agricola with exposure to a wider range of artistic styles and techniques, potentially including access to prints and paintings by leading European artists. The very act of being self-taught often implies a rigorous process of studying the works of others, experimenting with materials, and honing one's skills through persistent practice. Agricola's dedication to mastering the depiction of natural phenomena suggests a profound and personal connection to the landscapes he observed and later translated onto canvas and paper.

The Grand Tour and Artistic Pilgrimages: Shaping a Vision

A significant aspect of Agricola's career was his extensive travel, a practice common among ambitious artists of the period seeking to broaden their horizons and study firsthand the masterpieces of the past and the innovations of their contemporaries. His journeys took him to England, the Netherlands, France, and, crucially, Italy. Each of these destinations offered unique artistic environments and landscape traditions that would have contributed to the eclectic yet personal style he developed.

In the Netherlands, he would have encountered the rich tradition of Dutch Golden Age landscape painting. Artists like Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema had perfected the art of capturing the specific character of the Dutch countryside, with its flat horizons, dramatic cloudscapes, and meticulous attention to detail. The Dutch emphasis on naturalism and the depiction of everyday scenes, as well as their mastery of light, likely resonated with Agricola's own inclinations. Furthermore, the Italianate Dutch painters, such as Jan Both and Nicolaes Berchem, who brought sun-drenched Italian vistas to Northern European audiences, might have provided a bridge to the Mediterranean light he would later experience directly.

France, at this time, was dominated by the classical landscape tradition established by Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain. Poussin’s ordered, idealized landscapes, often featuring mythological or biblical narratives, emphasized structure and intellectual rigor. Claude Lorrain, on the other hand, was celebrated for his poetic, light-filled depictions of the Roman Campagna and harbor scenes, suffused with a golden, atmospheric haze. Agricola's work shows a clear affinity with these French masters, particularly in his compositional strategies and his pursuit of harmonious, often idyllic, landscape views. The influence of Gaspard Dughet, Poussin's brother-in-law, known for his more untamed and romanticized views of the Roman countryside, can also be discerned in Agricola's approach.

Italy, however, was the ultimate destination for many Northern European artists. Agricola spent a considerable period in Naples and also worked in Venice towards the end of his life. The Italian peninsula, with its dramatic coastlines, ancient ruins, and unique quality of light, offered inexhaustible subject matter. In Naples, he would have been exposed to a vibrant artistic scene and landscapes that differed significantly from those of Northern Europe. The city's surroundings, including Mount Vesuvius and the Bay of Naples, provided dramatic natural backdrops. His time in Venice, a city renowned for its luminous atmosphere and its own burgeoning school of view painters (vedutisti) like Luca Carlevarijs, a contemporary, and the slightly later Canaletto and Francesco Guardi, would have further refined his sensitivity to light and water.

Artistic Style: The Dawn of Baroque Romanticism

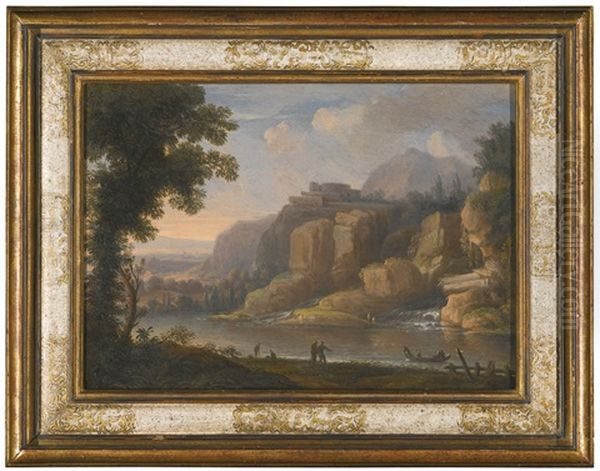

Agricola's style is most frequently described as an embodiment of "early Baroque Romanticism in German painting." This categorization points to a sensibility that, while rooted in Baroque principles of dynamism and rich detail, also anticipates the emotional engagement with nature characteristic of the later Romantic movement. His paintings are predominantly landscapes, often small-format "cabinet pictures" intended for intimate viewing and private collections. These works are distinguished by their profound naturalism and, most notably, his exceptional ability to render diverse atmospheric conditions and the subtle play of light and shadow.

He was particularly adept at capturing the specific moods associated with different times of day or weather events. Dusky twilights, the charged air before a thunderstorm, or the soft glow of a serene afternoon are all rendered with a convincing fidelity to observation. This focus on transient effects aligns him with artists who sought to convey not just the topography of a landscape but also its experiential and emotional qualities. While his compositions often draw on the idealized structures of Claude Lorrain or Poussin, Agricola infuses them with a more direct and palpable sense of atmosphere.

His handling of paint is typically refined, allowing for a detailed rendering of foliage, rock formations, and architectural elements, yet always subservient to the overall atmospheric unity of the scene. The figures that populate his landscapes are generally small, serving to animate the scene and provide scale rather than acting as the primary narrative focus. This subordination of the human element to the grandeur or mood of nature is another trait that leans towards a Romantic sensibility. The influence of Adam Elsheimer, an earlier German painter who worked in Italy and was known for his small, meticulously detailed landscapes on copper with innovative light effects, might also be considered a precursor to Agricola's approach to intimate, light-filled scenes.

Subject Matter: Beyond Idealized Landscapes

While primarily celebrated for his landscape paintings, Agricola's artistic output was more diverse. He demonstrated a keen interest in natural history, producing a significant body of watercolor studies, especially of birds. These works, often executed on vellum, showcase his meticulous observational skills and his ability to render fine detail with precision and delicacy. Such studies were part of a broader European fascination with the natural world during the 17th and 18th centuries, fueled by scientific exploration and the desire to catalogue and understand flora and fauna. These bird studies, in particular, were highly regarded and found a place in prominent French collections of the 18th century, indicating their perceived artistic and scientific value.

This engagement with natural history illustration complements his landscape work, suggesting an artist deeply attuned to the various facets of the natural environment. His ability to capture the specific plumage of a bird is akin to his skill in rendering the texture of a leaf or the quality of light on a distant mountain. Both require a sharp eye and a patient hand.

Furthermore, Agricola was an accomplished etcher. Etching, as a medium, allowed for the wider dissemination of his compositions and a different exploration of line and tone. His prints likely contributed to his reputation and the spread of his artistic ideas. The practice of printmaking was common among painters of the era, serving both as an independent artistic pursuit and a means of popularizing their painted works. The German tradition, with masters like Albrecht Dürer, had a long and distinguished history in printmaking, and Agricola would have been part of this continuing lineage.

Influences, Connections, and Artistic Milieu

Agricola's artistic development was clearly shaped by his engagement with the work of several key figures, primarily French and Italianate masters. The profound impact of Claude Lorrain is evident in the harmonious compositions and the luminous, atmospheric quality of many of Agricola's landscapes. From Nicolas Poussin, he likely absorbed principles of classical structure and the integration of figures within an ordered natural setting. Gaspard Dughet's influence can be seen in the slightly wilder, more romanticized aspects of some of his natural scenes.

Beyond these primary influences, his travels would have exposed him to a wide array of artistic currents. In the Netherlands, the works of landscape specialists like Jacob van Ruisdael, with his dramatic and moody depictions of nature, and Aelbert Cuyp, known for his golden light bathing Dutch landscapes and river scenes, would have offered valuable lessons in naturalism and atmospheric rendering. The Italianate Dutch painters, such as Jan Both, Nicolaes Berchem, and Karel Dujardin, who specialized in sun-drenched Italian scenes often populated with peasants and livestock, provided models for a type of landscape that proved highly popular across Europe and clearly resonated with Agricola.

Within the German-speaking lands, artists like Johann Heinrich Roos were known for their pastoral landscapes with a strong emphasis on animals, a theme that sometimes appears in Agricola's work as well. While direct collaborations are not extensively documented, Agricola's art did have an impact on subsequent painters. Notably, Christian Hilfgott Brand (sometimes referred to as Christian Hilgott von Freyland), an Austrian painter, is recorded as having been influenced by Agricola, discovering his own passion for painting through contact with Agricola's work. This suggests that Agricola, despite the limited biographical information available, was a recognized and respected figure whose art inspired others.

The Enigma of Agricola: A Life of Scant Detail

One of the intriguing aspects of Christophe-Ludwig Agricola is the relative scarcity of detailed biographical information, particularly concerning his training and the specifics of his day-to-day life and artistic practice. While his travels and the general trajectory of his career can be pieced together, the man himself remains somewhat elusive. This lack of extensive documentation is not entirely unusual for artists of his period who were not attached to major courts or academies for their entire careers, but it does add a layer of mystique to his persona.

His largely self-taught nature, if accurate, makes his achievements all the more impressive. It suggests an artist driven by an internal vision and a relentless pursuit of technical mastery through personal study and observation. This independence might also explain why he doesn't fit neatly into a specific "school" or workshop tradition, allowing him to synthesize diverse influences into a more personal style. The "mystery" surrounding his life perhaps encourages a greater focus on the works themselves, allowing them to speak directly to the viewer without the filter of extensive biographical anecdote. His paintings and etchings become the primary testament to his journey and his artistic concerns.

Representative Works and Their Characteristics

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be elusive, several works and types of works are characteristic of Agricola's oeuvre. Many of his paintings are titled descriptively, such as "Landscape with a Storm," "Italianate Landscape with Figures and Animals," "Southern Landscape with Shepherd and Flock," or "River Landscape with Fishermen." These titles immediately evoke the kinds of scenes he favored.

"Landscape with a Storm" would showcase his skill in depicting dramatic weather effects – dark, turbulent skies, wind-swept trees, and the particular quality of light that often precedes or follows a storm. These paintings capture nature's power and dynamism.

His "Italianate Landscapes" reflect his time in Italy and the influence of artists like Claude Lorrain and the Italianate Dutch painters. These works often feature rolling hills, classical ruins or rustic buildings, serene bodies of water, and figures (shepherds, travelers) that add a pastoral or picturesque element. The light in these scenes is typically warm and diffused, evoking the Mediterranean sun.

The "Southern Landscape with Shepherd and Flock" is a classic pastoral theme, popular since antiquity and revitalized during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Agricola's versions would emphasize the harmonious relationship between humanity and a benevolent, idealized nature.

His bird studies on vellum, such as "Study of a Parrot" or "Various Birds in a Landscape," are distinct for their precision and delicate coloring. These works highlight his versatility and his scientific curiosity, standing somewhat apart from his more atmospheric landscapes but sharing a common foundation of careful observation.

Legacy and Collections: Agricola's Enduring Presence

Despite the limited biographical details, Christophe-Ludwig Agricola's works found favor during his lifetime and after, entering various collections across Europe. His paintings were popular in cities like Dresden, Vienna, Florence, and Venice, indicating a broad appreciation for his style. Today, his art is preserved in numerous public museums, primarily in Germany and Italy, allowing contemporary audiences to engage with his vision.

In Germany, his works can be found in:

Brunswick (Braunschweig): Notably, the Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, one of Europe's oldest museums, which houses a significant collection of Old Master paintings. Other institutions in Brunswick that might hold related works or provide context include the Braunschweiger Landesmuseum (Brunswick State Museum), the Staatliches Naturhistorisches Museum Braunschweig (State Natural History Museum), and the Städtisches Museum Braunschweig (Municipal Museum).

Kassel: The Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Schloss Wilhelmshöhe is a key venue, but other Kassel institutions like the Museum Fridericianum (though now focused on contemporary art, it has a long history), the Neue Galerie (19th and 20th-century art), and the Naturkundemuseum im Ottoneum (Natural History Museum) contribute to the city's rich cultural landscape.

Schwerin: The Staatliches Museum Schwerin (State Museum Schwerin) boasts a significant collection, particularly strong in Dutch and Flemish painting, which provides a relevant context for Agricola's landscape art.

In Italy, his presence is marked in collections such as:

Florence: The prestigious Palatina Gallery, housed within the Palazzo Pitti, is a major repository of Renaissance and Baroque art, and Agricola's inclusion here speaks to his recognition.

Naples: Given his extended stay in the city, it's natural that his works would be found here. Museums like the Museo di Capodimonte, with its vast collection of Italian and European paintings, and potentially the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli (National Archaeological Museum), for its broader cultural context, are significant.

Turin and Bologna: These cities also hold examples of his work, further attesting to his Italian connections and the appeal of his landscapes to Italian collectors.

The dispersal of his works across these diverse and important collections underscores the esteem in which he was held and the enduring appeal of his atmospheric and sensitively rendered landscapes.

Conclusion: A Quiet Force in Baroque Landscape

Christophe-Ludwig Agricola remains a compelling figure in the history of German Baroque art. As a largely self-taught artist, he navigated the rich artistic currents of his time, absorbing influences from Dutch naturalism, French classicism, and the sun-drenched beauty of Italian landscapes. His unique talent lay in his ability to synthesize these elements into a personal style characterized by a profound sensitivity to atmosphere, light, and the emotional resonance of the natural world. His cabinet pictures, with their nuanced depictions of weather and time of day, mark him as a precursor to later Romantic sensibilities, earning him the description as a purveyor of "early Baroque Romanticism."

While the mists of time obscure many details of his life, his surviving paintings, etchings, and delicate watercolor studies of birds speak eloquently of his dedication, skill, and artistic vision. His works, found in esteemed collections across Europe, continue to offer viewers a tranquil yet evocative window onto the landscapes of the past, captured with a remarkable blend of naturalistic observation and poetic sensibility. Agricola's contribution, though perhaps quieter than some of his more famous contemporaries, is a significant thread in the rich tapestry of European landscape painting.