Claude-Louis Châtelet stands as a fascinating, albeit tragic, figure in late 18th-century French art. Born in Paris around 1753, he navigated the transition from the late Rococo to the burgeoning Neoclassical era, establishing himself as a talented painter and illustrator, particularly renowned for his landscape views. His life, however, was dramatically cut short by the political turmoil of the French Revolution, ending on the guillotine in Paris on May 7, 1795. Châtelet's career encapsulates the artistic tastes of his time, the importance of topographical illustration, and the dangerous intersection of art and politics during a period of profound upheaval.

Parisian Beginnings and Early Landscapes

Details surrounding Châtelet's early life and formal artistic training remain somewhat scarce. However, emerging as an artist in Paris during the 1770s, he quickly gained recognition for his skill in depicting landscapes, particularly the gardens and parks surrounding the capital. Working primarily in watercolor, gouache, and occasionally oil, he captured the fashionable estates and royal domains that were undergoing significant transformations, often reflecting the influence of the English landscape garden style.

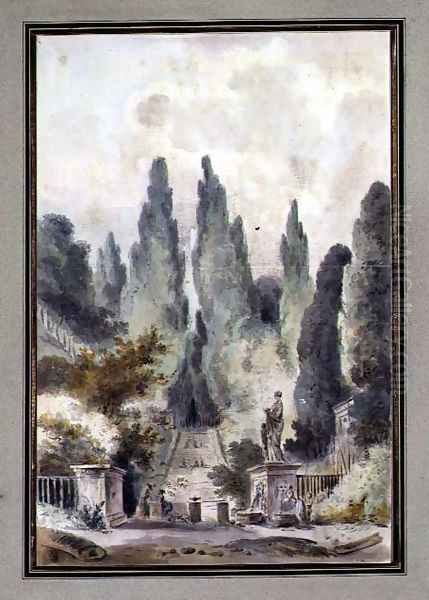

His subjects included picturesque views of the Parc de Belleville, the meticulously designed gardens of the Folie Saint-James in Neuilly-sur-Seine (a famous example of the Anglo-Chinese garden style), and scenes within the expansive grounds of the Palace of Versailles, including the intimate settings of the Petit Trianon, famously associated with Queen Marie Antoinette. These works often display a delicate touch, sensitivity to light and atmosphere, and a keen eye for architectural and botanical detail, characteristics that would define much of his output. His style shows an affinity with the clarity and topographical precision valued in the latter half of the century, perhaps absorbing influences from established landscape masters like Claude Joseph Vernet, known for his seascapes and Italianate views.

Documenting Switzerland: The Tableaux Pittoresques

A significant phase of Châtelet's career began with his travels to Switzerland between 1776 and 1780. He was commissioned, alongside other artists, to provide illustrations for a major publishing venture: the Tableaux topographiques, pittoresques, physiques, historiques, moraux, politiques, littéraires de la Suisse et de l'Italie. This ambitious project, spearheaded by Jean-Benjamin de La Borde and Baron Béat Fidèle de Zurlauben, aimed to provide a comprehensive visual and textual account of Switzerland.

Châtelet's contributions were numerous and vital. He traversed the Swiss cantons, sketching dramatic Alpine scenery, serene lakes, and charming villages. His watercolors and drawings from this period capture both the topographical accuracy demanded by the project and the burgeoning Romantic sensibility towards the sublime power of nature. These Swiss views were later engraved and became widely known through the publication, cementing Châtelet's reputation as a skilled landscape documentarian. This work placed him within a tradition of artists visually exploring and cataloging regions, a practice fueled by Enlightenment curiosity and the increasing popularity of travel.

The Italian Journey: Saint-Non's Voyage Pittoresque

Following his Swiss endeavors, Châtelet embarked on another crucial journey, this time to Southern Italy and Sicily. He traveled in 1778 with the Abbé Jean-Claude Richard de Saint-Non, a prominent art patron, collector, and amateur engraver, who was compiling his own monumental publication, the Voyage pittoresque ou Description des royaumes de Naples et de Sicile (published 1781-1786). This project aimed to document the landscapes, antiquities, and customs of the region, a popular destination for Grand Tour travelers.

Châtelet was a key artistic contributor to this venture, working alongside other notable artists like Jean-Louis Desprez, an architect and painter known for his dramatic, almost theatrical, views, and Dominique Vivant Denon, a multi-talented diplomat, writer, and artist who would later become the first director of the Louvre Museum under Napoleon. Together, they traversed the Italian south, sketching ancient Greek temples in Paestum and Sicily, the volcanic landscapes around Naples, coastal scenes, and picturesque ruins.

Châtelet is credited with providing a large number of the original drawings that were subsequently engraved for the Voyage Pittoresque. Other renowned artists also contributed views, including the master of romantic ruins, Hubert Robert, and potentially even Jean-Honoré Fragonard, though his involvement was less direct than Châtelet's. Jean-Pierre Houël was another contemporary artist extensively documenting Sicilian antiquities around the same time. Saint-Non's publication, richly illustrated thanks to the efforts of Châtelet, Desprez, Denon, and others, became immensely influential, disseminating images of classical antiquity and Italian scenery throughout Europe and contributing significantly to the Neoclassical visual vocabulary.

Artistic Style: Neoclassicism, Topography, and the Picturesque

Claude-Louis Châtelet's art occupies a space within the broader Neoclassical movement, yet it retains strong elements of the picturesque and topographical traditions. Unlike the grand historical narratives of Jacques-Louis David, the leading figure of French Neoclassicism, Châtelet focused on landscape. His work generally exhibits the clarity, order, and attention to detail associated with Neoclassicism, moving away from the lighter, more frivolous aesthetic of the Rococo, exemplified by artists like François Boucher.

His primary medium was often watercolor and gouache, applied with precision and delicacy. He demonstrated a fine control over light, often bathing his scenes in a soft, clear illumination that enhances the sense of place and atmosphere. His topographical works, like those for the Swiss and Italian publications, required accuracy in rendering terrain, architecture, and specific locations. However, he often imbued these scenes with a picturesque quality, selecting viewpoints that emphasized charming irregularity, textural contrasts, and harmonious compositions, aligning with contemporary aesthetic theories about landscape beauty.

Compared to the often dramatic, ruin-filled landscapes of Hubert Robert or the sublime, atmospheric seascapes of Claude Joseph Vernet, Châtelet's work can appear more restrained and descriptive, particularly in his garden views. Yet, his Italian and Swiss scenes sometimes hint at the sublime, capturing the grandeur of mountains or the evocative power of ancient ruins. He employed various techniques, using pen and ink to define forms, washes of watercolor for tone and color, and sometimes highlights in gouache. Oil paintings by him exist but are less numerous than his works on paper. His detailed approach often involved small, precise applications of paint or wash, building up texture, particularly in foliage or architectural elements.

Collaborations and Artistic Milieu

Châtelet's career was significantly shaped by his collaborations on large-scale publishing projects. His work alongside Jean-Louis Desprez and Dominique Vivant Denon for Saint-Non's Voyage Pittoresque is the most prominent example. This collaborative environment, involving patrons like Saint-Non and La Borde, and engravers who translated their drawings into prints, was typical of the era's illustration practices. These projects connected Châtelet with a network of artists, writers, and patrons interested in travel, antiquity, and the documentation of landscapes.

His contemporaries included not only the aforementioned collaborators (Desprez, Denon, Saint-Non) and contributors (Robert, Fragonard, Houël), but also other significant figures in French art. Jacques-Louis David dominated history painting, while Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun excelled in portraiture, famously painting Marie Antoinette. In landscape, besides Vernet and Robert, artists like Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes were developing theoretical frameworks for Neoclassical landscape painting, emphasizing direct study from nature alongside idealized compositions, drawing inspiration from earlier masters like Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin. Louis-Gabriel Moreau (l'aîné) was another contemporary specializing in landscapes of the Île-de-France, sometimes overlapping in subject matter with Châtelet's earlier work. Châtelet operated within this rich artistic environment, contributing his specific skills in topographical and picturesque landscape.

The Revolution's Shadow: Political Engagement and Execution

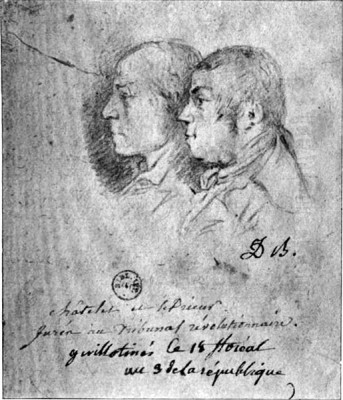

Beyond his artistic pursuits, Claude-Louis Châtelet became deeply involved in the radical politics of the French Revolution. He embraced the revolutionary cause with fervor, aligning himself with the Jacobins, the most radical political faction. His commitment led him to become a member of the Revolutionary Tribunal, the court instituted during the Reign of Terror (1793-1794) to prosecute perceived enemies of the Revolution.

This period saw intense political polarization and violence. Figures like Maximilien Robespierre, a leading Jacobin, wielded immense power. Châtelet's role on the Tribunal placed him in a position of authority during the Terror's height, participating in the judgments that sent many, including former patrons and members of the aristocracy, to the guillotine. His transformation from a painter of elegant gardens and picturesque landscapes to an active participant in revolutionary justice is stark and highlights the profound impact the Revolution had on individuals from all walks of life.

However, the political tides turned rapidly. Following the Thermidorian Reaction in July 1794, which led to the downfall and execution of Robespierre and his closest allies, those associated with the Reign of Terror faced retribution. Châtelet was arrested in Paris. Accused of abuses of power during his time on the Tribunal, he was tried and condemned to death. On May 7, 1795 (18 Floréal, Year III in the Republican calendar), Claude-Louis Châtelet was executed by the guillotine on the Place de Grève in Paris, bringing his life and promising artistic career to a brutal end at the age of about 42.

Legacy and Collections

Claude-Louis Châtelet's tragic end inevitably colors his legacy. For a time, his political activities during the Terror may have overshadowed his artistic contributions. However, his work remains significant, particularly his contributions to the great topographical publications of the late 18th century. His drawings and paintings offer valuable visual records of Swiss and Italian landscapes, classical sites, and French gardens as they appeared in his time.

His skill in watercolor and his ability to blend topographical accuracy with picturesque sensibility place him as an important practitioner of landscape art in the Neoclassical era. While perhaps not reaching the fame or influence of contemporaries like Hubert Robert or Jacques-Louis David, his extensive work as an illustrator ensured his images reached a wide audience through prints.

Today, works by Claude-Louis Châtelet can be found in major museum collections worldwide. The Musée du Louvre and the Musée Carnavalet in Paris hold examples of his work. Drawings and prints related to his travels are also housed in institutions like the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the British Museum in London, and various print rooms and libraries with significant collections of 18th-century graphic arts. His paintings occasionally appear at auction. Châtelet remains a compelling figure: a talented artist whose life reflects the aesthetic tastes of the Ancien Régime and the dramatic, fatal currents of the French Revolution. His art serves as a testament to the beauty he observed, while his life serves as a somber reminder of the turbulent times he lived through.