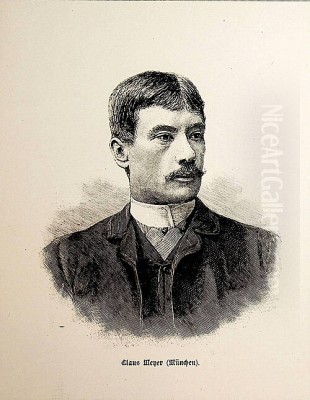

Claus Meyer (1856-1919) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in German art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A painter revered for his meticulous technique, his profound understanding of light, and his sensitive portrayal of domestic and religious life, Meyer carved a distinct niche for himself. His work, deeply rooted in the traditions of the Dutch Golden Age, offered a tranquil counterpoint to the more turbulent artistic currents of his time, such as Impressionism and the burgeoning Expressionist movement. This exploration delves into the life, influences, artistic output, and enduring legacy of a painter who masterfully captured the quiet dignity of everyday existence.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in Linden, near Hanover, Germany, in 1856, Claus Meyer's early life unfolded in a nation undergoing significant political and industrial transformation. The unification of Germany under Prussian leadership was on the horizon, and the societal shifts that accompanied this era undoubtedly formed a backdrop to his formative years. While detailed records of his earliest artistic stirrings are not extensively documented, it is clear that a strong inclination towards the visual arts emerged at a young age, leading him to pursue formal training. The environment of mid-19th century Germany, with its rich artistic heritage and burgeoning museum culture, would have provided ample inspiration for a budding artist.

The decision to become a professional painter was a significant one, often requiring not only talent but also dedication and the means to pursue rigorous academic training. Meyer's commitment to this path suggests a deep-seated passion for capturing the world around him, a passion that would be honed and refined in the art academies of Nuremberg and Munich. These cities were vibrant centers of artistic activity, each with its own distinct pedagogical approaches and influential figures, ready to shape the young artist's development.

Formal Artistic Training: Nuremberg and Munich

Claus Meyer's formal artistic education began in 1875 at the Nuremberg School of Art (Kunstgewerbeschule Nürnberg). Here, he studied under August von Kreling (1819-1876), a versatile artist known for his sculptures, paintings, and designs. Kreling, who also directed the school, would have instilled in Meyer a strong foundation in drawing and composition, essential skills for any aspiring academic painter. The Nuremberg school, with its emphasis on applied arts as well as fine arts, provided a comprehensive grounding.

Seeking to further his skills, Meyer moved to the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Munich (Akademie der Bildenden Künste München) in 1876, a pivotal step in his career. Munich at this time was a leading art center in Europe, rivaling Paris in certain respects, particularly for its robust tradition of history painting and realism. At the Munich Academy, Meyer had the privilege of studying under influential masters. One of his principal teachers was Alexander Wagner (1838-1919, also known as Sándor Wagner), a Hungarian-born painter celebrated for his large-scale historical canvases, often depicting dramatic scenes from Hungarian history. Wagner's tutelage would have exposed Meyer to the grand manner of academic history painting, emphasizing anatomical accuracy, complex figure arrangements, and narrative clarity.

Another key figure in Meyer's Munich education was Ludwig von Löfftz (1845-1910). Löfftz was highly regarded for his genre scenes and religious paintings, characterized by their technical polish, subtle lighting, and often somber, introspective mood. Löfftz's influence is perhaps more directly discernible in Meyer's mature work, particularly in his preference for interior scenes and his mastery of chiaroscuro. The Munich Academy, with its rigorous curriculum and exposure to diverse artistic personalities like Wilhelm Leibl, Franz von Lenbach, and Wilhelm von Kaulbach (who had taught Wagner), provided Meyer with the technical arsenal and artistic vision that would define his career.

The Enduring Influence of the Dutch Golden Age

A defining characteristic of Claus Meyer's art is his profound admiration for and emulation of the 17th-century Dutch Masters. He made numerous study trips to the Netherlands, immersing himself in the works of artists like Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) and Pieter de Hooch (1629-1684). This was not uncommon for artists of his generation; the Dutch Golden Age, with its focus on everyday life, meticulous realism, and masterful handling of light, held a particular appeal for painters seeking an alternative to the grandiosity of academic history painting or the fleeting impressions of the avant-garde.

From Vermeer, Meyer absorbed lessons in the depiction of light and its subtle interplay on surfaces, the creation of serene, contemplative atmospheres, and the portrayal of figures absorbed in quiet domestic activities. The intimate scale and psychological depth of Vermeer's interiors resonated deeply with Meyer's own artistic temperament. Similarly, Pieter de Hooch's skill in rendering complex interior spaces, his use of doorways and windows to create a sense of depth and connection between different rooms, and his charming depictions of family life, provided a rich source of inspiration.

Meyer was not merely a copyist; rather, he synthesized the techniques and thematic concerns of these Dutch masters into his own distinct visual language. He adopted their careful attention to detail, their rich but controlled color palettes, and their ability to imbue ordinary scenes with a sense of timeless dignity. This affinity for the Dutch "fijnschilders" (fine painters) set him apart and became a hallmark of his oeuvre. Other Dutch artists whose influence can be sensed include Gerard ter Borch, known for his elegant figures and exquisite rendering of textures, and Gabriel Metsu, a master of genre scenes.

Development of a Personal Style

While the Dutch influence was paramount, Claus Meyer's style was also shaped by his German academic training and the broader artistic currents of the 19th century. He developed a meticulous, highly polished technique, with smooth brushwork that often concealed the artist's hand, a characteristic valued in academic circles. His compositions are carefully constructed, demonstrating a strong sense of order and balance.

Meyer's figures are rendered with solidity and a quiet naturalism. They are often depicted in moments of introspection or gentle activity, avoiding overt drama or sentimentality. There is a palpable sense of stillness and peace in his best works, inviting the viewer to pause and contemplate the scene. His use of light is particularly noteworthy; it is often soft and diffused, illuminating interiors with a gentle glow that highlights textures and creates subtle gradations of tone. This mastery of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) lends a three-dimensional quality to his figures and objects, and contributes significantly to the overall mood of his paintings.

His color palette tends to be harmonious and restrained, often employing earthy tones, deep reds, and subtle blues and grays, reminiscent of the Dutch masters but sometimes infused with a slightly warmer, 19th-century sensibility. Unlike the Impressionists, such as Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, who were exploring broken color and the optical effects of light, Meyer remained committed to a more traditional, descriptive use of color to define form and create atmosphere.

Key Themes and Subjects in Meyer's Art

Claus Meyer's thematic concerns centered primarily on genre scenes, particularly tranquil domestic interiors, and religious subjects. These themes allowed him to explore his fascination with light, human psychology, and the quiet beauty of everyday life.

His domestic interiors often feature women engaged in quiet activities: reading, sewing, playing musical instruments, or simply lost in thought. These scenes are imbued with a sense of intimacy and serenity. Meyer excelled at capturing the textures of fabrics, the gleam of polished wood, and the play of light filtering through a window, transforming ordinary rooms into spaces of quiet contemplation. These works evoke a sense of bourgeois comfort and order, reflecting a common ideal of the period. He shared this interest in domesticity with artists like the French master Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin from an earlier era, and contemporary German realists.

Religious themes also formed an important part of Meyer's oeuvre. He often depicted scenes from the lives of saints or quiet moments of devotion, frequently set within monastic or church interiors. These paintings are characterized by their sincerity and respectful treatment of the subject matter, avoiding the overt theatricality that sometimes marked religious art of previous centuries. Instead, Meyer focused on the human element of faith and the spiritual atmosphere of sacred spaces. His depictions of nuns, for example, often emphasize their dedication and the peaceful rhythm of their communal life.

While less common, Meyer also undertook portrait commissions and contributed to larger decorative projects, demonstrating his versatility. However, it is his intimate genre scenes and thoughtful religious paintings that constitute the core of his artistic achievement and for which he is best remembered.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several paintings stand out as representative of Claus Meyer's artistic vision and technical skill. Among his most celebrated works is "In Front of the Mirror" (Stehend vor dem Spiegel). This painting depicts a young woman, elegantly dressed, standing before a mirror, seemingly absorbed in reading a letter. The composition is masterful, with the mirror not only reflecting the woman's face, allowing the viewer to glimpse her expression, but also extending the space of the room and adding complexity to the play of light. The meticulous rendering of her attire, the objects on the dressing table, and the subtle emotional undertones make this a quintessential Meyer piece.

Another significant work is "Music Lesson in the Beguinages" (Musikstunde im Beginenhof), also sometimes referred to as "Sewing School in the Beguinage" (Nähschule der Beginen), indicating a series or variations on a theme of life in a Beguinage. These paintings typically show a group of Beguines – lay religious women living in a community – engaged in activities like music instruction or needlework. The setting, a simple, light-filled room, evokes an atmosphere of quiet industry and spiritual devotion. Meyer's skill in depicting multiple figures interacting within a defined space, each with a sense of individual presence, is evident. The play of light, often streaming through a window to illuminate the scene, is handled with characteristic sensitivity, recalling the interiors of Vermeer or de Hooch.

Other works, though perhaps less universally known, further illustrate his thematic preoccupations and stylistic consistency. Paintings depicting solitary readers, families gathered in their homes, or quiet moments in church interiors all bear the hallmarks of his careful craftsmanship and his ability to find beauty and meaning in the ordinary. His dedication to these themes, executed with such technical finesse, solidified his reputation among connoisseurs of traditional painting.

The Academic Career: Professorships and Influence

Beyond his own studio practice, Claus Meyer made significant contributions as an educator. His strong academic grounding and recognized skill led to prestigious teaching appointments. In 1890, he was appointed professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Karlsruhe (Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste Karlsruhe). This position allowed him to impart his knowledge and artistic principles to a new generation of artists. Karlsruhe, like Munich, had a respected art academy, and Meyer's presence there would have reinforced its tradition of skilled figurative painting.

Later, in 1895, Meyer accepted a professorship at the renowned Düsseldorf Art Academy (Kunstakademie Düsseldorf). The Düsseldorf School had a long and distinguished history, particularly famous in the mid-19th century for its landscape and genre painting, with artists like Andreas Achenbach and Oswald Achenbach achieving international fame. By the time Meyer joined, the academy continued to be an important center for artistic training. His role as a professor in these institutions indicates the high regard ins which he was held within the German academic art world.

As a teacher, Meyer would have emphasized the importance of solid drawing skills, a thorough understanding of anatomy and perspective, and the careful study of the Old Masters, particularly those of the Dutch Golden Age. His own work served as a powerful example of these principles. While the tide of modernism was rising, with movements like Impressionism, Post-Impressionism (with figures like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne), and nascent Expressionism (led by groups like Die Brücke, including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner) challenging academic conventions, Meyer remained a staunch advocate for traditional craftsmanship and the enduring values of representational art. His students would have received a rigorous training that equipped them with formidable technical abilities.

Meyer and His Contemporaries: A Network of Artists

Claus Meyer was part of a vibrant artistic community and interacted with numerous contemporaries. During his studies and travels, he formed friendships and professional associations. He is known to have visited museums in Holland with fellow artists Paul Höcker (1854-1910) and Leopold von Kalckreuth (1855-1928). Höcker was a founding member of the Munich Secession in 1892, an association of artists who sought to break away from the conservative tendencies of the established art institutions and create new exhibition opportunities. Kalckreuth, also associated with the Secession movements, was known for his portraits and realistic depictions of rural life. These connections suggest Meyer was engaged with the progressive elements within the academic tradition, even if his own style remained more conservative.

He also undertook art study trips to Paris and Italy with his friend, the painter Hans Olde (1855-1917). Olde later became associated with German Impressionism and was instrumental in reforming art education in Weimar. These interactions with artists exploring different stylistic paths, from the academic realism of his teachers to the more modern sensibilities of some of his peers, provided a rich context for Meyer's own artistic development.

The German art scene of Meyer's time was diverse. While he adhered to a style rooted in earlier traditions, he worked alongside artists who were pushing boundaries. Max Liebermann (1847-1935), for instance, became a leading figure of German Impressionism. Adolph Menzel (1815-1905), an older contemporary, was a master of realism, renowned for his historical scenes and depictions of modern life. The Munich School, where Meyer trained, was itself a broad church, encompassing various approaches to realism and naturalism. Meyer's specific path, focusing on Dutch-inspired genre scenes, was a personal choice within this wider landscape, allowing him to cultivate a distinctive voice.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and International Presence

Claus Meyer's work gained considerable recognition during his lifetime, both within Germany and internationally. His paintings were exhibited in major art centers, including Berlin, Munich, and Düsseldorf. His participation in these exhibitions, often prestigious juried shows, solidified his reputation as a leading academic painter.

His appeal extended beyond German borders. Meyer's works were shown in London, Manchester, and even as far afield as New York, indicating an international appreciation for his refined style and tranquil subject matter. The acquisition of his work by institutions such as the Tate Gallery in London (though specific current holdings may vary) underscores the esteem in which he was held. Such international exposure was a mark of success for an artist of his era, demonstrating that his art resonated with a broader audience appreciative of technical skill and traditional aesthetics.

The awards and honors he received, alongside his professorial appointments, further attest to his standing in the art world. While he may not have courted the controversy or fame of some avant-garde figures, Meyer earned consistent respect for the quality and integrity of his artistic output. His paintings found favor with collectors who valued craftsmanship, quiet beauty, and a connection to the esteemed traditions of European art.

The Man Behind the Canvas: Dedication and Artistic Integrity

While detailed personal anecdotes about Claus Meyer are not as abundant as for some more flamboyant artistic personalities, his career speaks to a life of profound dedication to his craft. The meticulous nature of his paintings, the years spent in rigorous academic training, and his commitment to teaching all point to a serious and disciplined individual. His repeated study trips to Holland suggest an artist constantly seeking to deepen his understanding and refine his skills by engaging directly with the masterpieces that inspired him.

His choice of subject matter – serene domestic scenes, moments of quiet devotion – may also offer a glimpse into his personal values. In an age of rapid industrialization and social change, Meyer's art often seems to seek refuge in timeless human experiences: the comfort of home, the solace of faith, the quiet pursuit of everyday tasks. This focus suggests an appreciation for stability, harmony, and the enduring aspects of human life.

His role as an educator at Karlsruhe and Düsseldorf further highlights a commitment to preserving and passing on artistic knowledge. This dedication to fostering talent in younger generations is a significant, if less publicly visible, aspect of his contribution to the art world. He was part of a lineage of artist-teachers who ensured the continuity of technical skill and artistic understanding, even as aesthetic philosophies evolved.

Artistic Legacy and Later Assessment

Claus Meyer's legacy is primarily that of a master technician and a sensitive interpreter of quietude. In the context of art history, he is often seen as a representative of the late academic tradition in Germany, an artist who upheld the values of craftsmanship and representational accuracy in an era increasingly dominated by modernist experimentation. His adherence to a style inspired by the 17th-century Dutch Masters provided a distinct alternative to the prevailing trends of Impressionism, Symbolism, and the emerging Expressionist movements.

While the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century ultimately overshadowed many academic painters in the grand narrative of art history, there has been a renewed appreciation in recent decades for the skill and beauty found in the work of artists like Meyer. His paintings are valued for their technical excellence, their serene beauty, and their insightful portrayal of human experience. They offer a window into the cultural values and aesthetic preferences of his time, particularly those of the educated bourgeoisie who often patronized such art.

His influence can also be seen in the students he taught, who would have carried forward the principles of careful observation, solid draftsmanship, and masterful handling of light and color. Though art styles changed dramatically after his death in 1919, the fundamental skills he championed remain relevant. Museums and private collectors continue to cherish his works, which stand as testaments to a refined artistic sensibility and an unwavering commitment to a particular vision of beauty. He may not have been a revolutionary, but Claus Meyer was undoubtedly a master of his chosen domain.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Serenity

Claus Meyer navigated the complex artistic landscape of the late 19th and early 20th centuries with a clear vision and unwavering dedication to his craft. Drawing profound inspiration from the Dutch Golden Age, particularly masters like Vermeer and de Hooch, he created a body of work characterized by meticulous detail, subtle emotional depth, and an exquisite rendering of light. His tranquil domestic interiors and sincere religious scenes offer a peaceful counter-narrative to an era of burgeoning industrial and artistic upheaval.

Through his roles as a student at the esteemed academies of Nuremberg and Munich, under teachers like August von Kreling, Alexander Wagner, and Ludwig von Löfftz, and later as an influential professor in Karlsruhe and Düsseldorf, Meyer both absorbed and perpetuated a rich artistic tradition. His interactions with contemporaries such as Paul Höcker, Leopold von Kalckreuth, and Hans Olde placed him within a dynamic network of German artists, even as he pursued his distinct stylistic path.

Today, Claus Meyer's paintings are appreciated for their quiet beauty, their technical mastery, and their ability to transport the viewer to moments of serene contemplation. He remains a significant figure for those who value the enduring qualities of academic craftsmanship and the timeless appeal of genre painting. His legacy is that of an artist who found profound meaning in the everyday, capturing it with a skill and sensitivity that continue to resonate.