Introduction: The Artist and His Time

David de Coninck, born in Antwerp around 1636 and active until at least 1699, possibly later, stands as a significant figure within the rich tapestry of Flemish Baroque painting. Flourishing during a period of artistic vibrancy in the Southern Netherlands and beyond, De Coninck carved a distinct niche for himself as a specialist painter. He became particularly renowned for his lively and detailed depictions of animals, often set within lush landscapes or elaborate still-life compositions featuring flowers and fruit. His work embodies the energy and naturalism characteristic of the Baroque era, contributing significantly to the genre of animal painting, known as 'animalier' painting, in the 17th century.

While perhaps sometimes overshadowed by his direct predecessors or contemporaries, De Coninck's skill, particularly in rendering the textures of fur and feather and capturing the dynamic interactions between animals, earned him considerable recognition during his lifetime and ensures his place in the annals of art history. His career path, taking him from the artistic hub of Antwerp to the international melting pot of Rome and possibly back north, reflects the mobility and cross-cultural exchanges that shaped European art during this dynamic period.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

David de Coninck's artistic journey began in Antwerp, a city that, despite political and economic shifts, remained a powerhouse of artistic production in the 17th century. Born into this stimulating environment around 1636, the young De Coninck was positioned to absorb the strong traditions of Flemish painting, particularly the legacy of Peter Paul Rubens and his followers, which emphasized vibrant color, dynamic composition, and a robust naturalism.

Crucially, De Coninck entered the workshop of Jan Fyt (1611-1661), one of the leading animal and still-life painters of the generation after Frans Snyders (1579-1657). Fyt himself had trained with Snyders, inheriting and refining a style known for its detailed rendering of game, hunting scenes, and opulent still lifes. Under Fyt's tutelage, De Coninck honed his skills in capturing the anatomy, movement, and textures of various animals, from domestic fowl and pets to the spoils of the hunt. This apprenticeship provided the foundational techniques and thematic focus that would define much of De Coninck's subsequent career. The influence of Fyt is often discernible in De Coninck's work, though he would develop his own distinct variations on the themes and compositions favored by his master.

The Roman Experience: Joining the Bentvueghels

Like many Northern European artists of his time, David de Coninck felt the pull of Italy, the repository of classical antiquity and Renaissance masterpieces, and a vibrant center for contemporary art. He traveled to Rome, although the exact dates of his arrival and departure remain somewhat uncertain. His presence there is firmly documented by his membership in the Schildersbent, more commonly known as the 'Bentvueghels' (Dutch for "birds of a feather"). This confraternity of primarily Dutch and Flemish artists working in Rome was notorious for its bohemian lifestyle and initiation rituals, which often involved mock ceremonies and heavy drinking.

Within the Bentvueghels, artists adopted characteristic nicknames, or 'bent' names. De Coninck received the moniker "Rammelaar," which translates to "Rattler" or perhaps refers to a male rabbit or hare (known for drumming or rattling sounds), fitting for an animal painter. Alternatively, some sources suggest it means "Hedgehog." Life in Rome exposed De Coninck to Italian art, both old and new, including the developing traditions of landscape painting and the works of other animal specialists active in the city, such as the German painter Carl Borromäus Andreas Ruthart. He likely interacted with fellow Bentvueghels like Abraham Begeyn, known for his Italianate landscapes often featuring animals, and perhaps absorbed influences from the Bamboccianti, painters specializing in scenes of Roman popular life. This period undoubtedly broadened his artistic horizons and likely influenced his handling of light and landscape elements.

Artistic Style: Baroque Energy and Naturalistic Detail

David de Coninck's style is firmly rooted in the Flemish Baroque tradition, characterized by dynamism, rich textures, and a strong sense of naturalism. Building on the foundation laid by Jan Fyt, De Coninck excelled in depicting animals with remarkable vivacity and accuracy. His brushwork was often fluid yet precise, capable of rendering the softness of feathers, the sleekness of fur, or the rough texture of a game bird's plumage. He possessed a keen eye for animal behavior, often portraying creatures in motion – dogs lunging, birds fluttering, or cats poised to pounce.

His compositions are typically energetic and filled with life. While some works focus on single animals or small groups, many are complex arrangements featuring a variety of creatures interacting within a specific setting, often a landscape, garden, or interior space like a larder. His color palette tends to be rich and varied, reflecting the natural hues of the animals and their surroundings, often employing strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to enhance the dramatic effect and model form, a hallmark of the Baroque.

Compared to his teacher Jan Fyt, De Coninck's work might sometimes appear slightly less refined in finish, but it often possesses a raw energy and directness. While he mastered the depiction of birds, achieving considerable success in this area, some contemporary and later critics felt he didn't quite reach the supreme elegance of Fyt in this specific domain. Nevertheless, his ability to create convincing, lively scenes populated by animals was highly regarded. His style also shows an awareness of Dutch still-life traditions, particularly in the arrangement of elements and the use of color, blending these influences with his Flemish training and Italian experiences.

A World of Animals: Subjects and Themes

The core of David de Coninck's oeuvre revolves around the animal kingdom. He painted a wide array of creatures, demonstrating versatility within his chosen specialization. Domestic animals feature prominently, including various breeds of dogs (often hunting hounds), cats (sometimes depicted fighting, a popular motif), chickens, ducks, turkeys, peacocks, pigeons, and rabbits. These are frequently shown in farmyard or garden settings, contributing to the genre of pastoral or rural scenes.

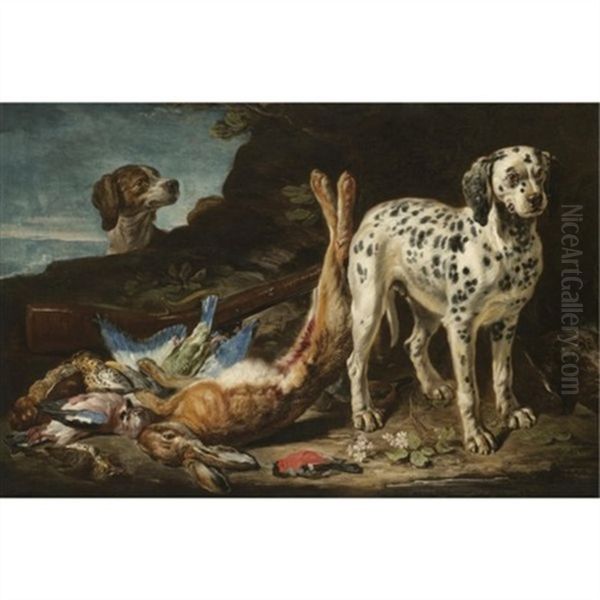

Game pieces and hunting still lifes were another major focus, continuing the tradition popularized by Frans Snyders and Jan Fyt. These works often depict dead hares, birds, and sometimes deer, arranged as trophies of the hunt, often accompanied by hunting dogs standing guard or surveying the spoils. De Coninck rendered these subjects with meticulous attention to detail, capturing the textures of fur and feathers and the limpness of the dead animals.

Beyond common domestic and game animals, De Coninck also occasionally included more exotic creatures, such as parrots, reflecting the growing European fascination with species imported from newly explored parts of the world. These brightly colored birds often added a touch of the exotic and luxurious to his compositions. His settings varied from detailed landscapes, sometimes with Italianate features suggesting his time in Rome, to more generic parklands or interiors. The narrative element in his works often centers on the natural interactions and instincts of the animals themselves – pursuit, confrontation, or repose.

Representative Works: Capturing Nature's Drama

While a definitive catalogue raisonné might be complex due to attribution issues, several works exemplify David de Coninck's style and thematic concerns. Titles often vary, but descriptive names frequently capture the essence of his paintings.

Works like Poultry in a Park Landscape or A Cock, Hens and Chicks with Pigeons and a Guinea Pig showcase his skill in composing lively scenes of domestic fowl in outdoor settings. These paintings are filled with movement and individual characterization of the birds. Similarly, depictions of peacocks, such as Peacock, Two Chickens and Two Rabbits (mentioned in the source material), allowed him to display his ability to render iridescent plumage and create visually splendid compositions.

His prowess in depicting hunting scenes and game is evident in works often titled Still Life with Dead Game and Dog or similar variations. These compositions typically feature a carefully arranged assortment of dead birds and perhaps a hare or rabbit, often watched over by one or more hunting dogs. The textures of fur, feathers, and the dogs' coats are rendered with convincing realism.

The painting described as Turkey, Two Dogs and Two Pigeons fits well within his known subject matter, combining domestic birds and dogs in a dynamic arrangement. Paintings featuring cats, sometimes in conflict, like Fighting Cats in a Larder, demonstrate his ability to capture animal aggression and movement within an interior setting, often surrounded by still-life elements. The work mentioned as Cat in the Wilderness (or similar titles like Cat Stalking Birds) highlights his focus on feline predators and their natural instincts, often placed within a detailed natural environment. These examples illustrate his consistent focus on animal life, rendered with Baroque energy and a commitment to naturalistic detail.

Later Career and Unresolved Questions

The latter part of David de Coninck's life and career is marked by some uncertainty, particularly regarding his movements and the precise date and place of his death. After his time in Rome, evidence suggests he may have worked in other European centers. Some art historians propose periods spent in Vienna and possibly Munich, although concrete documentation for extended stays can be scarce.

What seems more certain is his eventual return to the Low Countries. Contradicting earlier accounts that placed his death in Rome around 1687, stronger evidence indicates that he was active in Brussels towards the end of the century. Records show that a David de Coninck became a master in the Brussels Guild of Saint Luke (the painters' guild) in 1699. It is generally accepted that this was the same artist. Further records suggest his activity in Brussels continued until at least 1701.

After this point, the historical trail grows cold. It is therefore most likely that he died in Brussels sometime after 1701, rather than in Rome in 1687. This revised timeline places the end of his career firmly back in his native region, where he continued to practice his art and participate in the local artistic community through the guild system. The discrepancies in biographical accounts highlight the challenges historians sometimes face in reconstructing the lives of artists from this period, relying on often fragmented archival evidence.

Contemporaries, Influence, and Artistic Milieu

David de Coninck operated within a vibrant network of artists, both as a student and as a practicing master. His most significant relationship was undoubtedly with his teacher, Jan Fyt, whose influence shaped his technique and thematic choices. Fyt himself was a student of Frans Snyders, the great pioneer of Flemish Baroque animal and market scenes, establishing a clear lineage of specialization.

During his time in Antwerp and later possibly in Brussels, De Coninck would have been aware of other still-life and animal painters active in the region, such as Adriaen van Utrecht and Paul de Vos (Snyders' brother-in-law), who also excelled in large-scale, dynamic compositions. His connection with Pieter Boel, another Flemish painter who specialized in animals and still lifes and also spent time in Italy, is suggested by circumstantial evidence involving mutual acquaintances like the De Bie family (perhaps related to Cornelis de Bie, author of the important artists' biography Het Gulden Cabinet).

In Rome, his membership in the Bentvueghels placed him in contact with numerous Dutch and Flemish artists. Besides Abraham Begeyn and potentially Carl Ruthart, he might have known Karel Dujardin, another Bentvueghel member known for his Italianate landscapes with animals, or Nicasius Bernaerts, a Flemish animal painter who worked in both Italy and France.

De Coninck's own work found resonance with later artists. Notably, the celebrated Dutch painter Melchior de Hondecoeter, famous for his depictions of exotic birds in park settings, seems to have been influenced by or at least worked in a very similar vein to De Coninck. Some compositions by the two artists are remarkably alike, leading to occasional attribution difficulties. De Coninck's style also relates to the broader European tradition of animal painting, which included figures like Jakob Bogdani (Hungarian-born, active in England) and later Flemish painters like Pieter Casteels III. It is important to note, as the source material indicates, that David de Coninck is distinct from the Dutch painters Philip de Koninck (known for landscapes) and Salomon de Koninck (known for history paintings and portraits), despite the similarity in name.

Identity, Attribution, and Market Challenges

One of the persistent issues surrounding David de Coninck is the potential for confusion with other artists bearing similar names. While the distinction from the Dutch Konincks is clear, the source material itself mentions confusion with another "David de Coninck (1609-1687)," described as a famous Flemish animal/still life painter. However, standard art historical references primarily focus on the David de Coninck born c. 1636/1644 and active post-1701, who studied with Fyt and went to Rome. It's possible the source snippet reflects older or erroneous biographical traditions, or perhaps conflates details. The key figure discussed here is the one associated with Fyt, Rome, the nickname "Rammelaar," and the Brussels guild membership in 1699.

Further complicating matters are issues of attribution and signatures. The source material notes that De Coninck's signature was sometimes deliberately omitted or altered on his works, likely in attempts to pass them off as paintings by more famous or commercially valuable artists, perhaps even his master, Jan Fyt, or contemporaries like Hondecoeter. This practice, unfortunately not uncommon in the art market of the time, suggests that while De Coninck was respected, he may have faced competitive pressures. It also means that definitively attributing unsigned works in his style requires careful stylistic analysis by experts. These factors contribute to the ongoing scholarly work needed to fully delineate his oeuvre.

Market Presence and Legacy

Despite attribution challenges, works by David de Coninck appear regularly on the art market, indicating sustained interest from collectors. Auction records demonstrate that his paintings can command significant prices. The example cited of Paons, ardoises et oiseaux de basse-cour (Peacocks, Slates? and Barnyard Fowl) selling for €60,000-€70,000 at Drouot in Paris in 2013 attests to the high value placed on his major works. Another example mentions a still life with a parrot and fruit estimated at €9,000 at Galerie William Diximus, showing a market for smaller or different types of compositions as well. His works have been sold in major European auction centers, including Amsterdam, Paris, and likely London and Brussels, reflecting his international career and appeal.

Today, paintings attributed to David de Coninck can be found in various museums and private collections across Europe and potentially North America. While perhaps not as universally present in major museums as Snyders or Fyt, his works are held by institutions such as the Prado Museum in Madrid, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen, and various regional museums, including the Victoria Art Gallery in Bath (mentioned in the source for holding cat paintings, potentially his).

His legacy lies in his contribution to the specialized genre of animal painting within the Flemish Baroque. He successfully adapted the dynamic style of his predecessors and contemporaries to create lively, engaging, and naturalistic depictions of the animal world. His work provides a valuable window into the tastes and interests of the 17th century, particularly the appreciation for nature, the hunt, and the burgeoning interest in both domestic and exotic fauna. He remains an important figure for understanding the depth and diversity of Flemish art during its Golden Age.

Conclusion: An Enduring Contribution to Animal Painting

David de Coninck navigated the vibrant and competitive art world of the 17th century with considerable skill and success. From his formative years in Antwerp under the guidance of Jan Fyt to his experiences in the international artistic hub of Rome and his later activity in Brussels, he developed a distinctive and energetic style focused on the depiction of animals. His paintings, characterized by Baroque dynamism, rich textures, and keen observation of nature, capture the life and spirit of birds, mammals, and the hunt.

While facing challenges related to attribution and perhaps overshadowed at times by bigger names, De Coninck made a significant and lasting contribution to the animalier genre. His works were appreciated in his own time, influenced contemporaries like Melchior de Hondecoeter, and continue to be sought after by collectors and displayed in museums today. He stands as a testament to the high degree of specialization and technical brilliance achieved by Flemish painters during the Baroque era, leaving behind a body of work that celebrates the beauty, wildness, and vitality of the animal kingdom.