Edward Penny (1714-1791) stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 18th-century British art. A founding member of the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts and its first Professor of Painting, Penny contributed to the burgeoning artistic scene in London through his portraits, historical subjects, and genre scenes. His career reflects the artistic currents of his time, navigating the worlds of academic aspiration, public exhibition, and the evolving tastes of Georgian society.

It is crucial at the outset to distinguish Edward Penny, the 18th-century British painter, from other artists with similar or evocative names from different eras and disciplines. He is entirely distinct from Irving Penn (1917-2009), the celebrated 20th-century American photographer renowned for his fashion work, portraits, and still lifes. Similarly, he should not be confused with Edgar Alwin Payne (1883-1947), an American Impressionist painter famed for his landscapes of the American West, particularly the Sierra Nevada mountains, and author of "Composition of Outdoor Painting." The focus of this article is solely Edward Penny, the Georgian-era painter.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Knutsford, Cheshire, in 1714, Edward Penny was the son of Robert Penny, a surgeon. His twin brother, also named Robert, followed their father into the medical profession. From an early age, Edward displayed a strong inclination towards the arts. This passion led him to London, the burgeoning center of the British art world, to pursue formal training.

Around or before 1738, Penny became a pupil of Thomas Hudson (1701-1779), a leading portrait painter of the day. Hudson’s studio was a significant training ground for aspiring artists; notably, Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), who would become the dominant figure in British art, was also a pupil of Hudson, albeit slightly later than Penny. This shared tutelage under Hudson places Penny within a direct lineage of influential British portraitists.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, as was common for ambitious artists of the period, Penny traveled to Rome. Italy, with its unparalleled access to classical antiquities and Renaissance masterpieces, was considered an essential finishing school. In Rome, he studied under Marco Benefial (1684-1764), a respected Roman painter known for his opposition to the prevailing Rococo style and his advocacy for a return to the classical principles of Raphael and Carracci. Benefial's influence likely reinforced a more classical and perhaps a more serious, less flamboyant, approach in Penny's developing style compared to some of his contemporaries.

Return to England and Early Career

Edward Penny returned to England around 1748, equipped with the skills and experiences gained from his London apprenticeship and Roman studies. He began to establish his practice, focusing primarily on portraiture, which was the most reliable source of income for artists in 18th-century Britain. He painted small full-length portraits and "conversation pieces"—informal group portraits that were gaining popularity.

Beyond portraiture, Penny also ventured into historical and subject pictures, often with a moral or sentimental leaning. This aligned with a broader cultural trend in Georgian England that valued art not just for its aesthetic appeal but also for its capacity to instruct and edify. Artists like William Hogarth (1697-1764), though from a slightly earlier generation, had powerfully demonstrated the public appetite for narrative paintings with social commentary and moral lessons, such as his "A Rake's Progress" and "Marriage A-la-Mode."

Penny exhibited his works at the Society of Artists of Great Britain, which was one of the primary public venues for artists to display and sell their work before the founding of the Royal Academy. He also exhibited with the Free Society of Artists. These exhibitions were crucial for an artist's visibility and reputation.

The Royal Academy of Arts: A Founding Father

The most significant institutional development in British art during Penny's lifetime was the establishment of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768. This was a landmark moment, providing a formal structure for art education, exhibition, and the elevation of the status of artists in Britain. Edward Penny was among the thirty-six founding members, a testament to his standing within the artistic community.

The list of founding members reads like a who's who of mid-18th-century British art and architecture, including Sir Joshua Reynolds, who became its first President; Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), Reynolds' great rival in portraiture and a master of landscape; Benjamin West (1738-1820), an American-born painter who would succeed Reynolds as President and specialize in historical scenes; the Swiss-born Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807) and Mary Moser (1744-1819), the only two female founding members; landscape painters Richard Wilson (1714-1782) and Paul Sandby (1731-1809); and the architect Sir William Chambers (1723-1796), who played a key role in the Academy's formation.

Penny's involvement was not merely nominal. He was appointed as the Royal Academy's first Professor of Painting, a prestigious and influential position. He held this professorship from 1768 until 1782, delivering lectures to students on the theory and practice of painting. His role involved shaping the curriculum and guiding the next generation of artists, contributing to the codification of artistic training in Britain.

Furthermore, Penny designed the silver medal awarded by the Royal Academy. This medal, typically depicting Minerva (goddess of wisdom and arts) and a student, symbolized the arduous path and ultimate reward of artistic endeavor, reflecting the Academy's mission to foster excellence.

Artistic Style, Subject Matter, and Notable Works

Edward Penny's artistic output was diverse, encompassing portraits, historical subjects, and genre scenes, often imbued with a sense of narrative and sometimes a moralizing tone. His style was generally characterized by competent draughtsmanship, a clear and somewhat reserved palette, and compositions that effectively conveyed the story or captured the likeness of the sitter.

Portraits:

Like many of his contemporaries, Penny produced numerous portraits. While perhaps not reaching the fashionable heights of Reynolds or Gainsborough, his portraits were well-regarded. An example cited in auction records is "Portrait of an Officer," which appeared at Sotheby's in 2005. These works would have catered to the gentry and professional classes seeking to commemorate their status and likeness.

Historical and Subject Paintings:

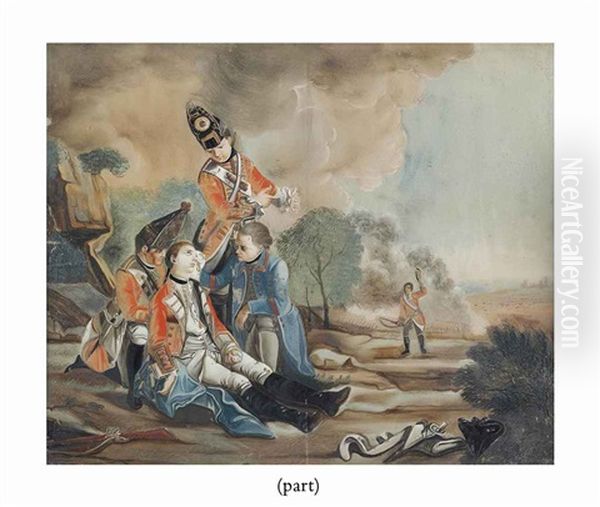

Penny engaged with the growing taste for historical and literary subjects. One of his most discussed works is The Death of General Wolfe (exhibited Society of Artists, 1764; now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford). This painting depicted the heroic demise of General James Wolfe at the Battle of Quebec in 1759, a pivotal moment in the Seven Years' War that resonated deeply with British national pride. Penny's version predates Benjamin West's more famous and revolutionary depiction of the same subject (1770), which broke with tradition by showing the figures in contemporary military attire rather than classical robes. Penny's treatment, while perhaps more conventional than West's later work, was an early example of this popular patriotic theme. Other artists like George Romney (1734-1802) and James Barry (1741-1806) also tackled grand historical themes.

Another significant work is The Marquis of Granby Relieving a Sick Soldier (1765; also Ashmolean Museum). John Manners, Marquis of Granby, was a popular military hero, and this painting depicts an act of benevolence, appealing to the sentimental tastes of the era. It showcases Penny's ability to handle narrative compositions with multiple figures and convey emotion. Such works highlighted virtues like compassion and duty, aligning with the didactic potential often ascribed to art.

Genre and Moralizing Scenes:

Penny also painted genre scenes, which depicted everyday life, often with an underlying message. The Gossiping Blacksmith (or The Idle Blacksmith) is one such example, likely shown at the Royal Academy's first exhibition in 1769. This type of work, focusing on the virtues of industry or the vices of idleness, found a ready audience. It echoes the tradition of moralizing genre painting established by Hogarth and continued by others like Francis Hayman (c. 1708-1776), who was also a founding member of the RA and known for his decorative history paintings and conversation pieces.

Other titles attributed to Penny, such as Apparent Dissolution and its companion pieces Virtue Rewarded and Profligacy Punished, further underscore his interest in subjects with a clear moral compass. These themes were popular in literature and theatre as well, reflecting a society grappling with social change and concerned with moral instruction.

His work Imogen Discovered in the Cave by Belarius, Guiderius, and Arviragus, taken from Shakespeare's Cymbeline, demonstrates his engagement with literary subjects, a field also explored by contemporaries like Henry Fuseli (1741-1825) with his dramatic and often sublime interpretations, or Francis Wheatley (1747-1801) known for his sentimental genre scenes and illustrations.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu of Georgian London

Edward Penny operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic environment. London in the mid-to-late 18th century was a hub of artistic activity, driven by increasing national wealth, a growing middle class with disposable income for art, and a desire to establish a distinctly British school of painting.

His master, Thomas Hudson, was a dominant force in portraiture before the rise of Reynolds. Sir Joshua Reynolds himself, as President of the RA, set the tone for much of the academic art of the period with his "Grand Manner" portraits and influential Discourses on Art. Thomas Gainsborough offered a more fluid, naturalistic, and often poetic alternative in both portraiture and landscape.

Benjamin West, an American who found great success in London, became a key figure in historical painting, particularly after the acclaim for his Death of General Wolfe. He, like Penny, was deeply involved in the Royal Academy. Other history painters included James Barry, known for his ambitious and sometimes controversial murals for the Society of Arts, and John Singleton Copley (1738-1815), another American who settled in London and produced dramatic historical scenes like Watson and the Shark.

In the realm of portraiture, besides Reynolds and Gainsborough, prominent names included Allan Ramsay (1713-1784), a Scottish painter who was a contemporary of Penny and held the post of Principal Painter in Ordinary to King George III, and George Romney, whose elegant portraits rivaled those of Reynolds in popularity for a time. Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797), while also a fine portraitist, became particularly famous for his "candlelight pictures" and scenes of scientific and industrial subjects, reflecting the Enlightenment's impact.

The founding of the Royal Academy also brought together artists with diverse specializations. Paul Sandby was a leading watercolorist and printmaker, often called the "father of English watercolour." Richard Wilson was a pioneering landscape painter, adapting the classical landscape tradition to British scenery. The presence of Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser highlighted the (albeit limited) opportunities for women artists at the highest levels. Kauffman, in particular, enjoyed international fame for her Neoclassical history paintings and portraits.

Penny's role as Professor of Painting placed him in a position to influence students who would go on to shape the next generation of British art, including figures like Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), who would become a leading portrait painter and future President of the Royal Academy, and J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), who would revolutionize landscape painting, though they would have been students towards the very end or after Penny's tenure.

Later Life, Legacy, and Art Historical Evaluation

Edward Penny continued to exhibit at the Royal Academy throughout the 1770s and into the early 1780s. However, his health began to decline, leading him to resign from his professorship in 1782. He was succeeded in this role by James Barry.

Penny spent his later years in Chiswick, then a village популярный with artists and writers on the outskirts of London. He passed away on November 15, 1791, and was buried in the churchyard of St. Nicholas, Chiswick. His wife, Grace, who was also a painter and exhibited miniatures at the Royal Academy, survived him.

In art historical terms, Edward Penny is perhaps not as widely celebrated as some of his more famous contemporaries like Reynolds, Gainsborough, or West. His work, while competent and representative of its time, did not possess the innovative flair or distinctive personal style that catapulted others to lasting international fame. He was a solid, professional artist who capably fulfilled commissions for portraits and produced subject pictures that resonated with the tastes and moral sensibilities of his era.

His most enduring legacy lies in his foundational role at the Royal Academy. As one of its initial members and its very first Professor of Painting, he contributed significantly to the institutionalization of art in Britain. His lectures, though their specific content is not extensively preserved, would have helped to establish the academic principles upon which generations of British artists were trained. The silver medal he designed continued to be an important symbol of academic achievement.

While some sources might anecdotally mention connections to industrial development or other non-artistic pursuits, these are likely confusions with other individuals named Penny from different contexts or periods. Edward Penny's career was firmly rooted in the world of painting and art education. His works can be found in collections such as the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the Royal Academy itself, and the Yale Center for British Art, allowing for continued study and appreciation.

Clarifying Confusions: Edward Penny vs. Irving Penn and Edgar Payne

To reiterate and expand for clarity, the Edward Penny discussed here (1714-1791) is distinct from two other notable artists whose names might cause confusion.

Irving Penn (1917-2009) was an American photographer of immense influence in the 20th century. His career spanned over six decades, much of it associated with Vogue magazine. Irving Penn was celebrated for his striking fashion photography, insightful portraits of cultural figures (such as Truman Capote, Pablo Picasso, Igor Stravinsky), and meticulously composed still lifes, including his "corner portraits" where subjects were posed in a tight, acute-angled space. His style was often characterized by its elegant simplicity, minimalist backgrounds, and masterful control of light, often in black and white. Representative works include Cuzco Children, Peru (1948), Woman in Chicken Hat (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn) (1949), and numerous portraits that defined an era of photographic modernism. He brought a classical sense of form and composition to photography, elevating commercial and fashion work to fine art.

Edgar Alwin Payne (1883-1947) was an American painter, primarily known for his powerful and atmospheric landscapes of the American West. Born in Missouri, Payne was largely self-taught. He became a leading figure in the California Impressionist movement. He was particularly drawn to the grandeur of the Sierra Nevada mountains, the deserts of the Southwest, and the coastal regions of California. Payne was a master of composition and color, often using a bold impasto technique. He co-founded the Laguna Beach Art Association and served as its first president. His influential book, Composition of Outdoor Painting, remains a valuable resource for artists. Notable works include The Sierra Divide, Solitude's Enchantment, and numerous depictions of Navajo people and their lands. His art captured the majestic and untamed spirit of the American landscape.

These brief summaries highlight the vastly different artistic worlds, time periods, and mediums of Irving Penn and Edgar Payne compared to the 18th-century British painter Edward Penny.

Conclusion

Edward Penny was a significant contributor to the British art scene of the 18th century. As a painter of portraits, historical subjects, and moralizing genre scenes, he reflected the artistic and cultural preoccupations of Georgian England. His role as a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts and its first Professor of Painting cemented his place in the history of British art, not as a revolutionary innovator, but as a dedicated professional and educator who helped to build the institutional framework that would support and shape British art for centuries to come. While perhaps overshadowed by some of the titans of his era, his work provides valuable insight into the artistic production and academic life of a pivotal period in British art history. His contributions, particularly to the nascent Royal Academy, ensured his influence extended beyond his own canvases, helping to foster an environment where British art could flourish.