Edward Robert Smythe stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art, particularly noted for his depictions of rural life and landscapes in his native Suffolk. Born in 1810 and active throughout much of the Victorian era until his death in 1893, Smythe developed a distinctive style rooted in careful observation and a deep affection for the English countryside and its inhabitants, both human and animal. While some later accounts have anachronistically labelled his work as Impressionist or Post-Impressionist, a closer examination places him firmly within the rich tradition of British landscape and genre painting, evolving alongside, but distinct from, the revolutionary movements emerging in France during his lifetime.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Edward Robert Smythe entered the world in Ipswich, Suffolk, in 1810. Born into a family that would also produce another notable artist, his younger brother Thomas Smythe (1825-1906), Edward's early inclinations reportedly leaned towards a military career. However, the allure of art proved stronger, leading him to pursue formal training. His artistic education included time spent associated with the Norwich School of Painting, a regionally important group that had significantly shaped British landscape art in the early 19th century.

During his studies, Smythe formed a friendship with Frederick Ladbrooke, the son of Robert Ladbrooke, one of the founding members of the Norwich School alongside the celebrated John Crome. This connection undoubtedly exposed Smythe to the principles of direct observation from nature and the focus on local scenery that characterized the Norwich School's ethos, influencing his own artistic direction. By 1832, his commitment to the local art scene was evident when he became a member of the Ipswich Society of Professional & Amateur Artists, signalling his establishment as a practising artist within his community.

Artistic Style: Observation and Realism

Smythe's artistic style is characterized by its detailed realism and focus on the textures and light of the Suffolk countryside. He worked proficiently in both oil and watercolour, capturing the specific atmosphere of East Anglia. His approach predates the broken brushwork and optical colour mixing of French Impressionism, which gained prominence in the 1870s and later. Instead, Smythe's work aligns more closely with the established traditions of British landscape painters like Thomas Gainsborough and John Constable, both of whom also had strong ties to Suffolk, and the later developments of Victorian genre painting.

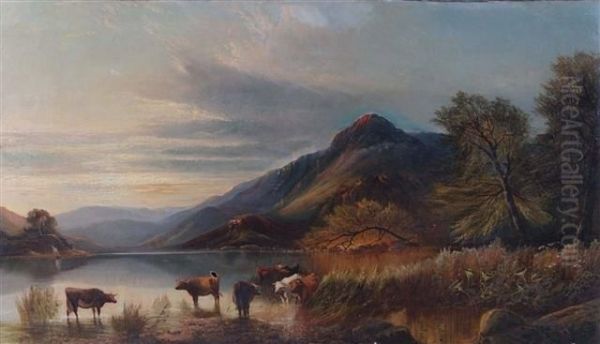

His paintings often feature a narrative element, depicting scenes of everyday rural activity – farmers at work, travellers resting, children playing, and animals in their natural settings. There is a tangible quality to his rendering of surfaces, whether it be the rough coat of a donkey, the weathered timber of a barn, or the play of light on water and foliage. While not an Impressionist in the conventional sense, his keen observation of light effects and atmospheric conditions demonstrates a sensitivity to the natural world that resonates with the broader 19th-century interest in landscape realism.

Key Themes and Representative Works

The subjects that populated Smythe's canvases were drawn directly from the world around him. Suffolk's gentle landscapes, its farms, coastal areas, and village life provided endless inspiration. He had a particular affinity for depicting animals, especially horses and donkeys, which he rendered with anatomical accuracy and individual character. Gypsy encampments were another recurring theme, offering a picturesque, slightly romanticized view of itinerant life that was popular in Victorian art.

Among his notable works are paintings that encapsulate these interests. The Gypsy Encampment explores a favourite theme, capturing a moment of rest and domesticity within a woodland setting (the creation date of 1810 cited in some sources is highly improbable, being his birth year, and the work likely dates from his mature period). Sketch for Ploughing, reportedly dating from 1848, showcases his interest in agricultural labour and his skill in capturing the dynamic movement of figures and animals within the landscape.

Another significant work often cited is The Colne Valley Viaduct, likely depicting the impressive Chappel Viaduct in Essex, near the Suffolk border. Such paintings demonstrate his ability to integrate man-made structures into the natural landscape harmoniously. A work titled A Group of Animals (for which an unlikely 1956 creation date has been erroneously cited) would exemplify his skill in animal portraiture, a field where he clearly excelled. These works, varied in subject matter, consistently display his commitment to detailed representation and atmospheric effect.

Career, Exhibitions, and Local Connections

Throughout his long career, Smythe sought recognition beyond his native Suffolk, exhibiting his works at prestigious London venues such as the Royal Academy and the British Institution. These exhibitions placed his work before a national audience, alongside contemporaries working in various styles. His participation in these shows indicates his ambition and his engagement with the broader British art world of the time.

Locally, however, Smythe remained deeply embedded in the Ipswich art scene. For a period, he maintained a studio in the Old Shire Hall in Ipswich, a space he shared with fellow artists Samuel Read, Walter Hagreen, Frederick Russell, and Robert Burrows. This arrangement suggests a collegial atmosphere among Ipswich artists, fostering mutual support and likely some degree of artistic exchange. His long-standing connection to the Ipswich Art Club (or its precursors) further cemented his position as a leading local painter.

The Smythe Brothers: A Comparison

Edward Robert Smythe's artistic journey is often considered alongside that of his younger brother, Thomas Smythe. Thomas also specialized in Suffolk landscapes and scenes of rural life, often featuring animals, particularly horses and dogs, as well as winter scenes, which became something of a trademark. Both brothers shared a similar artistic sensibility rooted in the local environment and Victorian tastes for narrative and realism.

Interestingly, while both were respected artists during their lifetimes, some accounts suggest that Thomas's work achieved greater commercial success, particularly in the art market revival for traditional British painting during the late 20th century, specifically the 1970s and 1980s. This later market preference does not necessarily reflect their respective talents or contemporary reputations but rather shifting tastes among collectors. Edward, however, maintained a steady career and contributed significantly to the artistic representation of Suffolk life.

Context within 19th-Century Art

Placing Edward Robert Smythe within the vast panorama of 19th-century art requires acknowledging the diverse currents of the era. He worked during a period of immense change. While he honed his skills in the tradition of British realism, artists across the Channel in France were forging new paths. The Barbizon School painters, like Jean-François Millet, were also focusing on rural life, but often with a different social or political undertone.

Later in Smythe's career, the French Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro, revolutionized painting with their focus on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light, and subjective perception, using radically different techniques. Following them, Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Paul Cézanne pushed artistic boundaries even further. While Smythe was aware of broader trends through London exhibitions, his own work remained largely independent of these continental innovations.

In Britain itself, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood offered a different kind of detailed realism infused with symbolism, while later British artists like Walter Sickert and Philip Wilson Steer eventually absorbed and adapted French Impressionist ideas. Smythe's contribution lies not in radical innovation but in the consistent quality and heartfelt depiction of his chosen subjects, representing a strong, regionally focused strand of Victorian art.

Later Recognition and Legacy

While perhaps overshadowed during periods when modernist styles dominated critical attention, Edward Robert Smythe's work has retained an enduring appeal, particularly for those interested in British landscape painting, animal art, and the social history of rural England. His paintings serve as valuable visual documents of Suffolk life in the 19th century, capturing agricultural practices, modes of transport, and the appearance of the landscape before widespread mechanization and development.

His reputation received renewed attention posthumously. The inclusion of his work in the Ipswich Art Club Centenary Exhibition in 1974 helped reintroduce his art to a modern audience. Furthermore, the art market has shown consistent interest in his work. A notable example is the sale of one of his paintings at Bonhams in London in 2011 for a significant sum (£39,560), indicating a strong collector base and a reappreciation of his skills and historical importance. This sale helped "regain some of the renown" he held during his lifetime.

Conclusion: A Suffolk Master

Edward Robert Smythe was a dedicated and skilled artist whose life and work were inextricably linked to the county of Suffolk. Born in 1810, he matured as an artist within the traditions of the Norwich School and British landscape painting, developing a style marked by careful observation, realistic detail, and a sympathetic portrayal of rural life and animals. He exhibited nationally but remained a key figure in the Ipswich art community, sharing studio space and contributing to local exhibitions.

Though not an innovator on the scale of the French Impressionists or Post-Impressionists, Smythe created a substantial body of work that captures the essence of Victorian Suffolk with charm and authenticity. His paintings of farmers, travellers, gypsy encampments, and especially his beloved horses and donkeys, continue to resonate with viewers. Alongside his brother Thomas, he helped define a particular vision of East Anglian art in the 19th century. His legacy endures through his paintings, which offer both aesthetic pleasure and a valuable historical window onto a bygone era of English rural life.