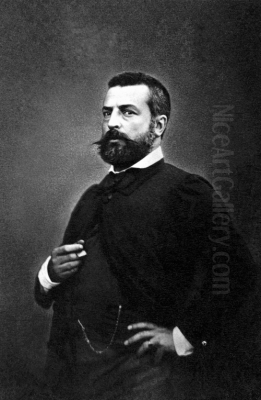

Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier stands as a towering figure in 19th-century French art, a painter and sculptor whose reputation during his lifetime reached extraordinary heights. Born in Lyon, France, on February 21, 1815, and passing away in Paris on January 31, 1891, Meissonier became synonymous with meticulous detail, historical accuracy, and a profound engagement with military history, particularly the Napoleonic Wars. His work, firmly rooted in the traditions of Academic art and a specific, highly finished form of Realism, earned him immense success, numerous accolades, and the admiration of collectors across Europe and America. Yet, his staunch adherence to tradition also placed him in opposition to the burgeoning modernist movements, leading to a complex legacy that continues to be debated and reassessed.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Meissonier's journey into the world of art was not immediate. Born into a family involved in business, his father initially intended for him to follow a more conventional path, leading to a brief period working as an apothecary. However, the young Ernest harbored a strong passion for drawing from an early age. Recognizing his son's talent and determination, his father eventually relented, allowing him to pursue artistic studies. This pivotal decision set Meissonier on a course that would define French art for decades.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who followed a strict academic path through the École des Beaux-Arts from the outset, Meissonier's early training was somewhat less conventional. He briefly studied in the studio of Jules Potier, a minor painter, and later spent time under the tutelage of Léon Cogniet, a more established historical and portrait painter associated with the Academic tradition. However, much of Meissonier's crucial development came from his own diligent efforts and self-directed study.

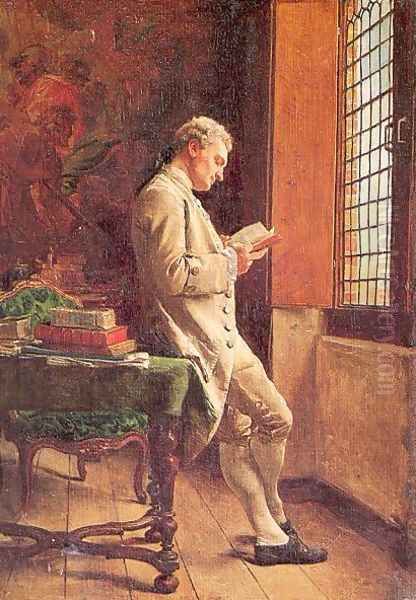

A significant part of his education involved countless hours spent at the Louvre Museum. There, he immersed himself in the works of the Old Masters, showing a particular affinity for the Dutch and Flemish painters of the 17th century. Artists like Gerard ter Borch and Gabriel Metsu, often referred to as the "Dutch Little Masters," captivated him with their small-scale genre scenes, exquisite rendering of textures, fabrics, and light, and their quiet, intimate portrayal of domestic or bourgeois life. This influence would become a cornerstone of his own artistic practice.

Meissonier's professional career began modestly, producing illustrations for various publishers. This work, while perhaps not artistically fulfilling in the long run, honed his skills in draftsmanship and composition. His official debut at the prestigious Paris Salon occurred in 1834 with a painting titled Les Bourgeois flamands (Flemish Burghers), also known sometimes as Visit to the Burgomaster. This early work already displayed the clear influence of the Dutch masters he admired, signaling the direction his art would take.

The Development of a Meticulous Style

From his early genre scenes inspired by Dutch art, Meissonier gradually shifted his focus, though he never entirely abandoned these subjects. His fascination with history, combined with a fervent patriotism and admiration for military prowess, led him increasingly towards historical and, most famously, military themes. The era of Napoleon Bonaparte, with its dramatic campaigns, iconic figures, and rich visual tapestry of uniforms and equipment, became a central preoccupation.

The defining characteristic of Meissonier's art, regardless of subject, was his extraordinary, almost obsessive, attention to detail. His style became synonymous with meticulous realism and historical accuracy. He undertook extensive research for his paintings, ensuring that every element, from the buttons on a uniform and the tack on a horse to the specific landscape features of a battlefield, was rendered with painstaking precision. This dedication to veracity set him apart and contributed significantly to his appeal.

To achieve this level of detail, Meissonier employed a highly controlled technique. His brushwork was fine and precise, often barely visible, creating smooth, highly finished surfaces. He built up his compositions with careful layering of paint, achieving subtle gradations of tone and color that enhanced the sense of realism. While his canvases were often relatively small, reminiscent of the Dutch masters he admired, the intensity of detail packed into them gave them a powerful presence.

His working methods were legendary for their thoroughness. He amassed a large collection of historical costumes, weapons, and props. He would often create scale models or stage scenes with live models dressed in authentic attire to study poses and lighting. For his military paintings, he famously conducted field research, studying horses in motion, observing military maneuvers, and even visiting battle sites to ensure the accuracy of his depictions. This almost scientific approach to realism was central to his artistic identity.

Major Themes and Representative Works

Meissonier's oeuvre primarily revolves around two major thematic areas: historical genre scenes, often set in the 17th and 18th centuries, and military subjects, dominated by the Napoleonic Wars. His genre paintings frequently depict gentlemen scholars, chess players, musicians, or cavaliers in richly detailed interiors, evoking the world of the Dutch Golden Age or the French Ancien Régime. Works like La Rixe (The Brawl, 1855), depicting a tavern fight with dramatic intensity and exquisite detail, brought him early acclaim and demonstrated his mastery in capturing human interaction and historical settings.

However, it was his Napoleonic paintings that cemented his fame and became his most iconic contributions. He approached these subjects with an epic sensibility, yet rendered them with the precision of a miniaturist. One of his most celebrated works is Campagne de France, 1814 (The Campaign of France, 1814), completed in 1864. This relatively small painting portrays a somber Napoleon on horseback, followed by his marshals, trudging through the muddy, snow-laden landscape during the disastrous retreat. The work captures the grim reality and exhaustion of war, focusing on the psychological weight carried by the Emperor, all rendered with Meissonier's signature detail.

Another monumental work, though physically larger than Campagne de France, is Friedland, 1807, finished in 1875 after more than a decade of work. This painting depicts Napoleon reviewing his cuirassiers after their victorious charge at the Battle of Friedland. Unlike the somber tone of Campagne de France, Friedland is a scene of triumphant energy, capturing the adulation of the troops for their leader. Meissonier meticulously painted each horse and rider, conveying the thunderous movement and gleaming armor of the cavalry charge. The painting was famously purchased by the American department store magnate A.T. Stewart for an enormous sum, later ending up in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Other significant works include Napoléon III à Solférino (Napoleon III at Solferino, 1863), depicting the French emperor observing the aftermath of the bloody battle during the Second Italian War of Independence, and Le Siège de Paris, 1870–1871 (The Siege of Paris), a patriotic allegory painted after the Franco-Prussian War, personifying the suffering and resilience of the besieged city. Even his landscape paintings, such as Antibes (1865), showcase his precise rendering of light and atmosphere, though they are less central to his fame.

Success, Recognition, and the Art Establishment

Meissonier's career was marked by almost unparalleled success and official recognition within the French art establishment. From his early Salon entries, he consistently garnered praise and awards. He received numerous medals at the Salons throughout the 1840s and 1850s, solidifying his reputation. His works commanded exceptionally high prices, making him one of the wealthiest artists of his time.

His success was not confined to France. His paintings were highly sought after by collectors internationally, particularly in Great Britain and the United States. Wealthy American industrialists, such as William H. Vanderbilt (who eventually acquired Friedland, 1807 after Stewart's death), were eager patrons, viewing his work as the pinnacle of contemporary European art. This international acclaim further boosted his standing.

The French state showered him with honors. He was elected to the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1861, the official body overseeing artistic standards in France. His highest honor came with his elevation within the Légion d'honneur (Legion of Honour), France's premier order of merit. He progressed through its ranks, ultimately receiving the Grand-Croix (Grand Cross) in 1889, a distinction rarely awarded to artists and signifying his immense national stature.

In 1890, towards the end of his life, Meissonier played a key role in a schism within the established Salon system. He became the first president of the newly formed Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, which organized its own, more liberal exhibitions, often referred to as the "Salon du Champ-de-Mars." While this might seem like a move towards reform, it was more about internal politics within the academic world than an embrace of the avant-garde. Meissonier remained fundamentally aligned with the conservative art establishment throughout his career.

Contemporaries, Influences, and Students

Meissonier's long and prominent career placed him at the center of the Parisian art world, interacting with numerous other artists, both allies and rivals. His primary influences, as noted, were the Dutch and Flemish masters of the 17th century, whose meticulous technique and genre subjects he adapted. His teachers, Jules Potier and Léon Cogniet, provided foundational training within the French academic system.

Among his contemporaries, his relationship with Eugène Delacroix, the leader of the Romantic school, was one of mutual respect despite their stylistic differences. Delacroix is known to have admired Meissonier's technical skill. A more complex relationship existed with Gustave Courbet, the leading figure of the Realist movement. While both artists aimed for a form of realism, Courbet's socially conscious, often gritty and unidealized subjects, combined with his looser brushwork, stood in stark contrast to Meissonier's polished, historical focus. Meissonier famously opposed Courbet, particularly after the latter's involvement in the Paris Commune.

Meissonier also worked during the rise of Impressionism, a movement fundamentally opposed to his aesthetic principles. Artists like Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas challenged the very notions of finish, detail, and subject matter that Meissonier championed. While stylistically poles apart, there were occasional points of intersection; for instance, both Meissonier and Degas showed an interest in capturing movement, particularly of horses, and Degas reportedly used some of the same models or drew inspiration from Meissonier's studies for works like Jockeys before the Grandstands. However, Meissonier generally represented the artistic establishment against which these avant-garde painters rebelled. He was often grouped with other highly successful Academic painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme and William-Adolphe Bouguereau, who also enjoyed immense fame and official favor during this period.

Despite his fame, Meissonier did not cultivate a large school of direct followers in the way some other masters did. His most notable student was Édouard Detaille, who became a highly successful painter of military subjects in his own right, clearly influenced by Meissonier's style and thematic interests. Meissonier's son, Jean Charles Meissonier, also became a painter, working in a style similar to his father's and achieving some recognition, including receiving the Legion of Honour in 1889. However, the extreme demands of Meissonier's technique perhaps made his style difficult to emulate widely.

Meissonier and the Rise of Modernism

The latter half of Meissonier's career coincided with the emergence and consolidation of Impressionism and other modernist tendencies in art. Meissonier, as a pillar of the Academic establishment and a champion of traditional values of craftsmanship, historical accuracy, and high finish, found himself increasingly positioned as the antithesis of the avant-garde.

His art was criticized by proponents of modernism for being overly meticulous to the point of appearing labored and photographic, lacking spontaneity and emotional expression. They saw his historical subjects as backward-looking and irrelevant to contemporary life. His immense commercial success also led to accusations of pandering to bourgeois tastes and prioritizing financial gain over artistic innovation. The Impressionists, with their focus on capturing fleeting moments of modern life, subjective perception, light, and color, offered a radical alternative that made Meissonier's detailed realism seem static and old-fashioned to progressive critics.

Meissonier, for his part, held the new movements in low regard, viewing their work as unfinished and lacking in skill and discipline. His opposition to Courbet and his general alignment with the conservative juries of the official Salon placed him firmly in the camp resisting artistic change. This stance, combined with the shifting tides of taste, meant that even during his later years, while still immensely popular and respected, the foundations of his aesthetic were being challenged.

The rise of modernism ultimately led to a significant decline in Meissonier's critical reputation after his death. For much of the 20th century, his work was often dismissed as merely illustrative, technically proficient but artistically empty, representing the staid academicism that modern art had overthrown. His name became shorthand for the kind of official art that the Impressionists and subsequent modernists had rebelled against.

Later Life, Death, and Legacy

Ernest Meissonier remained active and highly regarded until his death in Paris on January 31, 1891, at the age of 76. His passing was marked by significant public mourning and tributes, reflecting his status as a national figure. He was lauded as one of the greatest artists of his time, a master craftsman whose work brought glory to France. His funeral was a major event, attended by prominent figures from the art world and the state.

However, as the influence of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and subsequent modernist movements grew, Meissonier's star began to fade. His meticulous realism fell dramatically out of fashion. For decades, his paintings were relegated to secondary status in museum collections and art historical narratives, often cited primarily as examples of the academic tradition that modernism had superseded.

In the later 20th and early 21st centuries, a more nuanced reassessment of 19th-century academic art began to take place. Art historians started to look beyond the modernist narrative and re-evaluate artists like Meissonier on their own terms. His incredible technical skill, his profound knowledge of history, his ability to construct complex narrative scenes, and his significant role within the cultural landscape of his time are now more widely acknowledged.

Today, Meissonier's works are held in major museums around the world, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Wallace Collection in London, and many others. While his style remains distinct from the main trajectory of modern art, he is recognized as a master of his chosen genre. His legacy is that of an artist who achieved the highest levels of success and technical perfection within the academic tradition, creating enduring images of history, particularly the Napoleonic legend, rendered with an unparalleled, if sometimes controversial, devotion to detail. He remains a key figure for understanding the complexities and competing aesthetics of the vibrant art world of 19th-century France.