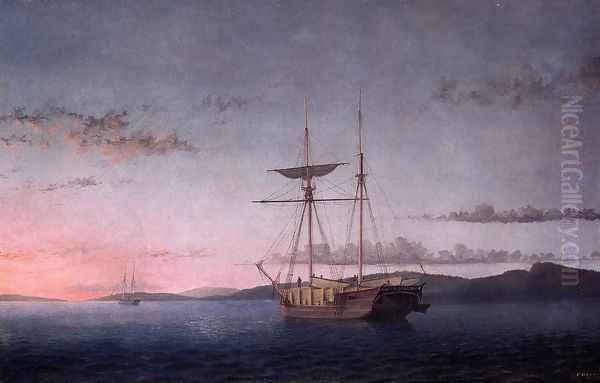

Fitz Henry Lane stands as a pivotal figure in nineteenth-century American art. Primarily celebrated as a master of marine painting and a key proponent of the style known as Luminism, Lane captured the unique light and atmosphere of the New England coastline with unparalleled sensitivity and precision. His canvases, often depicting tranquil harbors, reflective waters, and luminous skies at dawn or dusk, evoke a sense of profound stillness and spiritual connection with nature. Though his name was obscured for a time, and even his given name commonly mistaken, his work has been rightfully restored to a place of prominence, recognized for its technical brilliance, poetic sensibility, and significant contribution to the American landscape tradition.

Early Life and Overcoming Adversity

Born Nathaniel Rogers Lane on December 19, 1804, in the bustling fishing port of Gloucester, Massachusetts, the artist faced significant challenges from a young age. His father, Jonathan Dennison Lane, was a sailmaker, deeply connected to the maritime world that would later dominate his son's art. Tragedy struck early when, around eighteen months old, Lane consumed poisonous seeds (possibly from the Apple Peru or Nicandra physalodes), resulting in paralysis of his legs. This condition necessitated the use of crutches throughout his life.

Despite this physical limitation, Lane developed a keen eye and a determined spirit. Growing up surrounded by the ships, wharves, and coastal scenery of Gloucester provided an endless source of inspiration. His disability may have even focused his attention more intensely on observation, fostering the meticulous attention to detail that would become a hallmark of his work. He began drawing and sketching in his youth, largely self-taught, honing his skills by capturing the world immediately around him.

Formative Years in Boston

Seeking formal training and broader opportunities, Lane moved to Boston around 1832. He secured an apprenticeship at William S. Pendleton's renowned lithography firm, one of the most important printmaking establishments in the country at the time. This period was crucial for his artistic development. Working as a lithographer demanded exceptional draftsmanship, precision, and an understanding of tonal values, skills that translated directly into his later painting practice. Pendleton's shop was a hub of artistic activity, exposing Lane to various styles and techniques.

During his time in Boston, Lane encountered the work of Robert Salmon, an accomplished English-born marine painter who had settled in the city. Salmon's detailed ship portraits and harbor views, characterized by their crisp rendering and atmospheric effects, exerted a significant influence on the young Lane. He absorbed Salmon's approach to depicting water, light, and maritime architecture. It was also during this period, in 1831, that Nathaniel Rogers Lane formally petitioned the Massachusetts legislature to change his name to Fitz Henry Lane, the name by which he would become known in the art world. He remained at Pendleton's, and later successor firms, until the mid-1840s, producing numerous lithographic views of towns, buildings, and landscapes.

Return to Gloucester and Artistic Maturity

Around 1848, Lane returned to his hometown of Gloucester, now an established artist. He continued to produce lithographs but increasingly focused on oil painting. In 1849, alongside his brother-in-law Ignatius Winter, Lane designed and built a distinctive granite house on Duncan's Point, offering panoramic views of Gloucester Harbor. This home became his studio and sanctuary, providing constant inspiration for his mature works.

His return marked a shift towards the subjects and style for which he is most famous. While he had painted marine scenes earlier, his Gloucester years saw him refine his vision, concentrating on the interplay of light, water, and atmosphere along the Massachusetts and Maine coasts. He developed a deep intimacy with the local environment, observing the subtle shifts in light at different times of day and under various weather conditions. His paintings from this period demonstrate a growing mastery of composition, color, and the rendering of tranquil, light-filled spaces.

The Essence of Luminism: Lane's Style

Fitz Henry Lane is considered one of the foremost practitioners of Luminism, a distinct movement or style within nineteenth-century American landscape painting, often seen as an offshoot of the Hudson River School. While sharing the Hudson River School's reverence for nature, Luminism, as exemplified by Lane, typically favored quieter, more contemplative scenes over the dramatic wilderness vistas often painted by artists like Thomas Cole or Frederic Edwin Church.

Lane's Luminist style is characterized by several key elements. He employed meticulous detail and a smooth, often invisible brushstroke, creating highly polished surfaces that enhance the sense of realism and stillness. Compositionally, his works frequently feature strong horizontal lines – the horizon, shorelines, calm water – contributing to a feeling of stability and expanse. Perhaps most importantly, Lane was a master of light. He favored the soft, diffused light of dawn or twilight, capturing the way it reflects off water and illuminates the atmosphere with a palpable, often ethereal glow. His handling of air and space creates a sense of deep, quietude, inviting contemplation. This focus on light and atmosphere finds parallels in the work of Dutch Golden Age masters like Jacob van Ruisdael, though Lane's sensibility remained distinctly American.

Exploring the New England Coast

Lane's artistic explorations were not confined to Gloucester. He made numerous sketching trips along the New England coast, venturing frequently to Maine. Areas around Castine, Rockland, and particularly Mount Desert Island became favorite subjects. These excursions provided fresh material and perspectives, allowing him to capture the rugged beauty of the Maine shoreline, contrasting it with the more familiar harbors of Massachusetts.

His travels often involved sailing, giving him firsthand experience of the sea and ships he depicted with such accuracy. An anecdote, possibly apocryphal but indicative of his dedication, suggests he sometimes had himself lashed to the mast of a ship during rough weather to better observe the dramatic effects of sea and sky. Whether true or not, his paintings demonstrate an intimate understanding of maritime life and the natural forces governing the coast. These trips resulted in iconic works depicting locations like Owl's Head, Penobscot Bay, and Somes Sound, further solidifying his reputation as a premier marine painter.

Representative Masterpieces

Several paintings stand out as exemplary of Fitz Henry Lane's mature style and contribution to American art. Boston Harbor (versions exist, e.g., c. 1850-55, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) is often cited as a quintessential Luminist work. It depicts the harbor in a state of serene calm, bathed in the warm, horizontal light of late afternoon or early morning. The water acts as a near-perfect mirror, reflecting the meticulously rendered ships and the luminous sky. The painting exudes tranquility and order, showcasing Lane's mastery of light, detail, and composition.

The Brace's Rock series (painted in the early 1860s, examples in the National Gallery of Art and Cape Ann Museum) explores a specific location near Gloucester under different conditions, often conveying a more somber or melancholic mood, perhaps reflecting the artist's later years or the looming Civil War. These works demonstrate his ability to infuse landscapes with emotional resonance through subtle variations in light and atmosphere. Other significant works include Becalmed off Halfway Rock (c. 1860), capturing a moment of absolute stillness at sea, and Twilight on the Kennebec (c. 1849), an early example of his fascination with the effects of twilight. His Dream Painting (c. 1860-65), a more allegorical work, suggests deeper spiritual or philosophical underpinnings to his art.

Transcendental Connections

The pervasive sense of calm, order, and spiritual presence in Lane's work has often led scholars to connect his art with the Transcendentalist philosophy prevalent in New England during his lifetime. Thinkers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau advocated for finding divinity and spiritual truth through direct experience of nature. Lane's paintings, with their emphasis on quiet contemplation, harmonious compositions, and the almost mystical quality of light, seem to resonate with these ideas.

While there's no direct evidence Lane formally adhered to Transcendentalism, his friendship with figures associated with the movement and the prevailing intellectual climate make the connection plausible. His works can be interpreted as visual meditations on the beauty and inherent spirituality of the natural world, particularly the liminal spaces where water, land, and sky meet. The clarity and stillness he achieved suggest a desire to represent not just the physical appearance of a scene, but its underlying essence and the profound peace it could inspire. His engagement with Spiritualism, another contemporary movement, might also inform the ethereal quality found in some of his later works.

Lane's Circle: Teachers, Contemporaries, and Students

Fitz Henry Lane's artistic journey was shaped by interactions with various figures. His early influence, Robert Salmon, provided a model for detailed marine painting. His time at William S. Pendleton's firm placed him alongside other aspiring artists like Benjamin Champney, who would also become a noted landscape painter associated with the White Mountains.

Lane, in turn, became a mentor himself. His most notable student was Mary Blood Mellen (1819-1886). Mellen worked closely with Lane, particularly in the 1850s, sometimes collaborating on paintings or creating copies of his work. Her style closely mirrors Lane's, demonstrating his significant impact as a teacher. Distinguishing their hands can sometimes be challenging for art historians, attesting to the quality of her work under his guidance.

Within the broader context of American art, Lane occupies a unique position. He is associated with the Hudson River School generation, which included figures like Asher B. Durand, the aforementioned Cole and Church, and John Frederick Kensett. Kensett, along with Sanford Robinson Gifford and Martin Johnson Heade, are often grouped with Lane as key Luminist painters, sharing an interest in atmospheric effects and serene compositions. While influenced by European traditions, perhaps even the light-filled canvases of J.M.W. Turner or the compositions of Claude Lorrain, Lane forged a distinctly American vision, focused on the specific character of the New England coast.

Rediscovery and Legacy

Despite his regional reputation and steady production, Fitz Henry Lane was largely forgotten by the broader art world in the decades following his death from cancer on August 14, 1865. He was buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in Gloucester. The rise of Impressionism and other modern styles shifted critical attention away from the meticulous realism of Luminism.

However, the early twentieth century saw a renewed interest in nineteenth-century American art. Lane's work began to be rediscovered by collectors and scholars, notably after collector Maxim Karolik championed his paintings in the 1930s and 1940s. Exhibitions and publications gradually brought his achievements back into focus. Today, Lane is recognized as one of the most important American painters of his era. His works are highly sought after and held in major museum collections, including the Cape Ann Museum (which holds the largest single collection), the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. His legacy lies in his masterful depiction of light and atmosphere, his quintessential renderings of the New England maritime world, and his central role in defining the Luminist aesthetic.

A Note on the Name

For much of the twentieth century, the artist was commonly referred to as "Fitz Hugh Lane." This error likely stemmed from confusion or misinterpretation in early records or publications, possibly compounded by the existence of relatives with similar names (a nephew named Fitz Hugh Lane died tragically in 1915). However, meticulous research conducted by the Cape Ann Museum archives, culminating in findings published around 2004-2005, definitively established his correct name. Archival documents, including his official 1831 petition to the state legislature, confirm that he changed his name from Nathaniel Rogers Lane to Fitz Henry Lane. While the "Fitz Hugh" moniker persists in some older texts, "Fitz Henry Lane" is now accepted as historically accurate by scholars and major institutions.

Conclusion

Fitz Henry Lane's art offers a unique window into the maritime soul of nineteenth-century New England. Through his luminous canvases, he transformed familiar coastal scenes into poetic meditations on light, stillness, and the quiet grandeur of nature. Overcoming physical adversity, he honed a precise technique, first through lithography and then oil painting, to capture the subtle nuances of atmosphere and reflection with extraordinary skill. As a leading figure of American Luminism, his work provides a counterpoint to the more dramatic strains of the Hudson River School, emphasizing harmony, clarity, and a profound sense of peace. Though once overlooked, Fitz Henry Lane now holds an enduring place as a master painter whose radiant, tranquil visions continue to captivate and inspire.