Francesco Malacrea, an Italian painter of the 19th century, carved a niche for himself through his dedicated exploration of still life and marine subjects. Born in the vibrant artistic crucible of Venice in 1812, and passing away in the same city in 1886, Malacrea's life and work are intertwined with the rich visual traditions of his native region, particularly the Venetian penchant for color and light, and the maritime atmosphere of port cities like Venice and Trieste. Though perhaps not as widely known internationally as some of his contemporaries, his contributions to the regional art scene, especially in Trieste, and his thematic preoccupations, mark him as a noteworthy figure in the landscape of 19th-century Italian art. His oeuvre reflects a deep engagement with the transient beauty of nature, the evocative power of the sea, and a profound connection to his cultural heritage.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Venice

Francesco Malacrea's journey as an artist began in Venice, a city that had for centuries been a beacon of artistic innovation and a hub for painters captivated by its unique interplay of light, water, and architecture. Growing up in such an environment undoubtedly shaped his visual sensibilities from an early age. The legacy of Venetian masters, from Titian and Tintoretto with their dramatic use of color and dynamic compositions, to Canaletto and Guardi with their meticulous vedute capturing the city's splendor, would have formed the backdrop of his artistic consciousness.

While specific details about his earliest training remain somewhat elusive, it is known that Malacrea came under the tutelage of Enrico Hohbergher. Hohbergher himself was a painter who shared Malacrea's thematic interests, focusing on nature morte (still life) and marine subjects. This master-student relationship was likely pivotal in cementing Malacrea's own artistic direction. Hohbergher's guidance would have provided Malacrea with technical skills and a framework for approaching these genres, which were well-established yet always open to fresh interpretation. The tradition of still life painting, with its roots in the Dutch Golden Age and its subsequent development across Europe, offered a field for exploring texture, form, and the symbolic meanings of objects. Similarly, marine painting, a genre with strong traditions in Venice and other maritime centers, allowed for the expression of nature's power and beauty, as well as the human relationship with the sea.

The artistic education in 19th-century Italy, particularly in established centers like Venice, often involved rigorous training in drawing, perspective, and the study of Old Masters, alongside emerging academic trends. Malacrea's development would have occurred within this context, where respect for tradition coexisted with the stirrings of new artistic movements that were beginning to challenge academic conventions across Europe.

Thematic Focus: Nature Morte and the Allure of the Sea

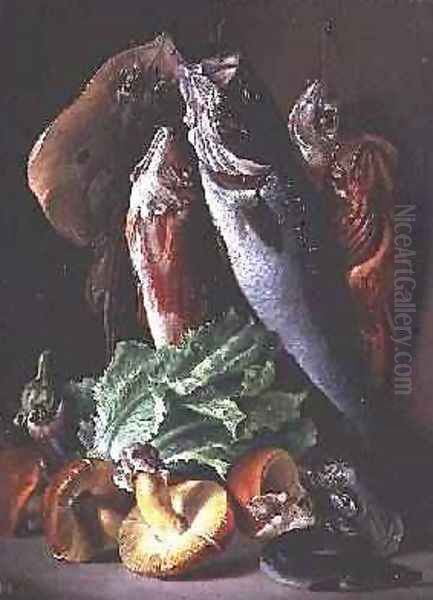

Francesco Malacrea's artistic output was significantly characterized by his dedication to two primary themes: nature morte (still life) and marine subjects. These genres, while distinct, both offer profound opportunities for artists to explore concepts of transience, beauty, and the natural world.

Nature morte, literally "dead nature," is a genre that often delves into the ephemeral quality of life. By meticulously depicting arrangements of objects—flowers, fruits, game, household items—artists can meditate on themes of mortality (vanitas), the bounty of nature, or simply the aesthetic pleasure of form, color, and texture. Malacrea's engagement with still life, often referred to by the German term "Stilleben" in some records, suggests a deep interest in capturing the intricate details and inherent beauty of these assembled objects. His still lifes likely reflected the Venetian tradition's emphasis on rich color and tactile surfaces, inviting viewers to appreciate the materiality of the depicted items and the artist's skill in rendering them.

Parallel to his still life work, Malacrea was drawn to marine themes. For an artist rooted in Venice and active in Trieste, another significant port city, the sea was an omnipresent and powerful source of inspiration. Marine painting could encompass a wide range of subjects, from tranquil coastal scenes and bustling harbor views to dramatic shipwrecks and depictions of naval battles. Malacrea's marine works are described as reflecting his deep affection for his "hometown city," which, given his activity, likely refers to the maritime character of both Venice and Trieste. These paintings would have captured the atmospheric conditions of the Adriatic, the play of light on water, and the diverse forms of maritime life and vessels. His approach to these themes was noted for its connection to a "Venetian style," implying a certain vibrancy and sensitivity to color and light.

A recurring motif in his work is described as "natural death," which bridges his still lifes (often featuring game or cut flowers) and potentially some aspects of his marine art (perhaps depicting the raw, untamed aspects of the sea or the remnants of marine life). This focus suggests a romantic sensibility, an awareness of the cyclical nature of life and the sublime power of the natural world.

Artistic Milieu: Trieste's Circolo Artistico and Venetian Connections

While Venice was his birthplace and the city of his death, Francesco Malacrea became an important figure in the artistic community of Trieste. During the 19th century, Trieste, then a vital port of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, had a burgeoning cultural scene. Malacrea was an active member of Trieste's Circolo Artistico (Artistic Circle), an association that brought together local artists for exhibitions, discussions, and mutual support. Such circles were crucial for fostering artistic development and creating a sense of community among artists in regional centers.

Within the Circolo Artistico, Malacrea would have interacted with other prominent artists of the region. Among his contemporaries and associates in Trieste was Eugenio Scomparini (1845-1913), a versatile painter known for his historical scenes, portraits, and genre paintings, often imbued with a romantic or patriotic sentiment. Scomparini, like Malacrea, was a significant presence in Trieste's art world, and their association within the same artistic circle suggests shared platforms for exhibiting work and exchanging ideas.

Another artist mentioned in connection with Malacrea and the Trieste art scene is Carlo Wostry (1865-1943). Although Wostry was younger and his career peaked later, the artistic circles of a city like Trieste often involved interactions across generations. Wostry became known for his Orientalist themes, portraits, and large-scale decorative works, contributing significantly to the artistic landscape of Trieste in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The environment of the Circolo Artistico would have been a place where artists like Malacrea could showcase their particular specializations, such as his marine paintings and still lifes, contributing to the diversity of the local art scene.

Malacrea's art, with its focus on themes deeply connected to the maritime identity of Trieste and its Venetian stylistic underpinnings, found a receptive audience and played a role in shaping the city's artistic discourse. His participation in local exhibitions would have helped to popularize genres like still life and marine painting, demonstrating their continued relevance and potential for artistic expression.

Style, Technique, and the "Flame Style"

Francesco Malacrea's artistic style is generally characterized as being rooted in the Venetian tradition, which historically prioritized color (colorito) over drawing (disegno). This implies an approach where the expressive qualities of color, light, and atmosphere were paramount. His still lifes and marine paintings would likely have exhibited a richness of palette and a sensitivity to the way light interacts with surfaces, whether it be the sheen on a piece of fruit, the texture of a game bird's feathers, or the reflective quality of water.

A more enigmatic description associated with his work is the "flame style." This term is not a standard art historical classification and could be interpreted in several ways. It might refer to a particularly vibrant, almost incandescent use of color, perhaps with warm hues predominating, creating a sense of energy and intensity. Alternatively, it could describe a dynamic, flickering quality in his brushwork, lending a sense of movement and vitality to his subjects. Given his focus on natural elements and the sea, a "flame style" could also metaphorically suggest the passionate intensity with which he approached his subjects or the dramatic interplay of light and shadow, akin to the flickering of a flame. Without specific visual examples widely available for analysis, the precise meaning remains somewhat speculative, but it hints at an expressive and perhaps non-conventional aspect of his technique.

His teacher, Enrico Hohbergher, also focused on nature morte and marine themes, suggesting a continuity of interest and perhaps stylistic approach. It is plausible that Malacrea built upon Hohbergher's foundations, developing his own distinct voice within these shared genres. The connection to Trieste's artistic circles, including figures like Eugenio Scomparini, further situates his work within a regional context where local traditions and broader European trends intersected.

The creation of still life, or "Stilleben," requires meticulous observation and a high degree of technical skill in rendering textures, volumes, and the interplay of light. Malacrea's dedication to this genre indicates a commitment to these traditional artistic virtues. Similarly, marine painting demands an understanding of the sea's moods, the structure of ships, and the often-dramatic effects of weather and light, all of which would have been part of his artistic arsenal.

Representative Works and Thematic Exploration

While a comprehensive catalogue of Francesco Malacrea's works is not readily available, his primary representative pieces are identified as his still life paintings ("Stilleben"). One specific, though generically titled, work mentioned is "Still life." This title, common in the genre, encompasses a vast range of potential subjects: arrangements of flowers, fruit, game, fish, or domestic objects. Given his thematic interest in "natural death" and marine subjects, it is plausible that his still lifes often featured elements like freshly caught fish, game birds, or crustaceans, themes that were popular in Venetian and Dutch traditions and allowed for a rich display of textures and colors.

His marine paintings, though not individually titled in the provided information, formed a significant part of his oeuvre. These works were inspired by his deep connection to his maritime surroundings, particularly Venice and Trieste. They likely depicted various aspects of the Adriatic coast, from tranquil harbor scenes with fishing boats to more dynamic portrayals of the sea. The "Venetian style" attributed to these works suggests a focus on atmospheric effects, the luminous quality of light on water, and a rich, nuanced color palette. Artists like Ippolito Caffi (1809-1866), a Venetian contemporary known for his vedute and dramatic nocturnal or atmospheric scenes (including naval engagements), or Guglielmo Ciardi (1842-1917), another Venetian celebrated for his evocative seascapes and lagoon views, represent the kind of artistic environment and thematic concerns that Malacrea would have been familiar with and possibly responded to in his own marine art.

The recurring theme of "natural death" in Malacrea's work is particularly intriguing. In still life, this could manifest in the depiction of hunted animals or wilting flowers, traditional memento mori subjects that remind the viewer of life's transience. In a maritime context, it might translate to scenes of shipwrecks, the raw power of storms, or even the depiction of beached marine life, all underscoring the formidable and sometimes destructive forces of nature. This thematic concern aligns with broader Romantic sensibilities prevalent in the 19th century, which often emphasized emotion, individualism, and the sublime beauty and terror of the natural world.

The preservation of some of Malacrea's works by the collector Antonio Fonda Savio was crucial, especially considering that a portion of his artistic legacy was reportedly damaged during the bombing of Venice in 1945. This act of collection highlights the value attributed to his work by connoisseurs of his time or shortly thereafter.

Later Years, Death, and Enduring Legacy

Francesco Malacrea's later years appear to have been marked by personal hardship. It is reported that he suffered from severe paralysis, a debilitating condition that would have profoundly impacted his ability to paint and engage with the world. This illness mirrors the tragic fate of his teacher, Enrico Hohbergher, who also suffered from progressive paralysis and ultimately died by suicide in 1897 due to depression linked to his condition. While the provided information sometimes conflates details between Malacrea and Hohbergher, Malacrea's own death occurred earlier, in 1886, in his native Venice. The circumstances of his death are not as dramatically detailed as Hohbergher's, but the mention of paralysis suggests his final years may have been challenging.

Despite these personal struggles, Malacrea left behind a body of work that contributed to the artistic fabric of 19th-century Italy, particularly within the Venetian and Triestine spheres. His dedication to still life and marine painting, infused with a "Venetian style" and perhaps his unique "flame style," offered a personal interpretation of these enduring genres. His involvement with the Circolo Artistico in Trieste underscores his role as an active participant in the regional art scene, contributing to its vitality and discourse.

The fact that his works were collected by individuals like Antonio Fonda Savio and that some were unfortunately lost to the ravages of war speaks to their perceived value. Malacrea's art, with its focus on the beauty of the natural world, the evocative power of the sea, and the poignant theme of transience, resonated with the sensibilities of his time and continues to hold interest for art historians studying the regional artistic currents of 19th-century Italy.

His influence on other artists is an area that warrants further research. The provided information suggests a connection to Gino Rossi (1884-1947), a significant Venetian painter of a later generation known for his post-impressionist and modernist explorations. If Malacrea's work did indeed attract the attention of artists like Rossi, it would indicate that his paintings possessed qualities that transcended their immediate context and appealed to artists seeking new expressive paths. Rossi himself was influenced by artists like Gauguin and Cézanne, and his work often featured bold colors and simplified forms, particularly in his depictions of Breton and Venetian scenes. Any influence from Malacrea would likely have been in terms of thematic inspiration or a shared Venetian sensibility towards color and light, rather than direct stylistic imitation.

Other painters active in Venice during or overlapping Malacrea's time, such as Giacomo Favretto (1849-1887), known for his lively genre scenes of Venetian life, or Luigi Nono (1850-1918), who also painted genre scenes and poignant depictions of human emotion, help to paint a picture of the diverse artistic environment in which Malacrea operated. Even earlier figures in Italian still life, like Evaristo Baschenis (1617-1677) with his renowned musical instrument still lifes, or Cristoforo Munari (1667-1720), represent the rich tradition of the genre in Italy upon which later artists, including Malacrea, could draw. In the broader Italian context of the 19th century, artists like Filippo Palizzi (1818-1899), though from Naples, were also making significant contributions to realism and the depiction of animals and everyday life, reflecting a wider European interest in these themes.

Conclusion: Reappraising Francesco Malacrea

Francesco Malacrea emerges as a dedicated artist who, within the specific confines of still life and marine painting, sought to capture the essence of his subjects with a distinctly Venetian sensibility. His life, spanning from 1812 to 1886, placed him in a dynamic period of Italian art, witnessing the persistence of academic traditions alongside the rise of new movements. His activity in both Venice and Trieste connected him to important regional artistic centers, and his participation in Trieste's Circolo Artistico highlights his engagement with his contemporaries.

While he may not have achieved the widespread fame of some Italian masters, his commitment to his chosen genres, his exploration of themes like "natural death" and the maritime world, and his stylistic leanings—described as "Venetian" and evocative of a "flame style"—mark him as an artist of interest. The tragic circumstances of his later life, possibly marked by paralysis, add a poignant dimension to his story, echoing the hardships faced by his own teacher, Enrico Hohbergher.

The legacy of Francesco Malacrea resides in his surviving works, preserved through the foresight of collectors like Antonio Fonda Savio, and in his contribution to the cultural life of Trieste and Venice. His paintings offer a window into the artistic preoccupations of his time, reflecting a deep appreciation for the transient beauty of the natural world and the enduring allure of the sea. Further research and potential rediscovery of his works could shed more light on his specific contributions and solidify his place within the narrative of 19th-century Italian painting, alongside contemporaries like Eugenio Scomparini and within the broader lineage of Venetian art that includes figures from Caffi and Ciardi to later innovators like Gino Rossi, and in the context of European still life masters such as Paul Cézanne or earlier Italian specialists like Munari and Baschenis.