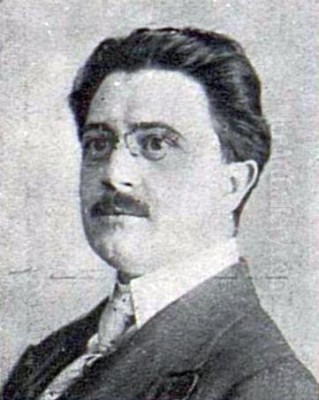

Francisc Sirato stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of Romanian modern art, a multifaceted artist whose career spanned painting, graphic arts, art criticism, and theoretical innovation. Born in Craiova in 1877 and passing away in Bucharest in 1953, Sirato's life and work were deeply intertwined with the cultural and socio-political transformations of Romania in the first half of the 20th century. His artistic journey reflects a profound engagement with contemporary European art movements, yet it remained distinctly rooted in a desire to express a unique Romanian sensibility. From his early satirical graphics to his mature post-impressionistic and symbolist paintings, and his forward-thinking "Dimensionist Manifesto," Sirato left an indelible mark on his nation's artistic heritage.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Francisc Sirato's artistic inclinations emerged early, leading him to pursue formal art education in Bucharest, the burgeoning cultural capital of Romania. The artistic environment at the turn of the century was one of transition, with academic traditions gradually giving way to modern influences filtering in from Paris and other European centers. It was in this milieu that Sirato began to hone his skills and develop his artistic voice.

His initial foray into the public art scene was significantly through graphic arts and satirical cartoons. Collaborating with various newspapers, Sirato's drawings often provided sharp, incisive commentary on the social and political issues of the day. This early work demonstrated a keen observational skill and a penchant for capturing the essence of human character and societal dynamics. His graphic style was influenced by prominent Romanian graphic artists of the time, including Iosif Iser, known for his socially conscious themes and modernist leanings, and Ary Murnu (Aristomene Murnu Gheorghiades), another significant caricaturist and illustrator. These influences helped shape Sirato's critical perspective and his ability to communicate complex ideas through visual means.

The Balkan Wars and the First World War brought profound upheaval to Romania and the wider European continent. These tumultuous times deeply impacted Sirato, and his art began to reflect the new, harsh realities of conflict and its aftermath. Works from this period, such as the series sometimes referred to by the name of a publication he was associated with, Popasul Satelor (which can be interpreted as "The Village Stop" or metaphorically, "The Satirist"), depicted scenes of refugees, soldiers, and the general populace grappling with the dramatic changes. These pieces were not mere reportage but carried an emotional weight and a critical eye, showcasing his evolving humanism.

Evolution of Artistic Style

As Sirato matured as an artist, his focus shifted more towards painting, though he never entirely abandoned his critical graphic work. His painterly style underwent a significant evolution, absorbing and reinterpreting various contemporary European artistic currents. He became particularly known for his adeptness in color and light, hallmarks of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

Impressionistic Sensibilities

In his earlier paintings, Sirato demonstrated a clear affinity for Impressionistic techniques. He was captivated by the play of light and color in rendering landscapes, still lifes, and portraits. His brushwork became more broken, his palette brightened, and he sought to capture fleeting moments and atmospheric effects. Works like Still Life with Vase and Roses exemplify this phase, showcasing a delicate observation of natural details and a concern for the optical effects of light on surfaces. This approach was shared by other Romanian artists who were looking towards French Impressionism, such as Nicolae Grigorescu, a foundational figure in modern Romanian painting, and later, Ștefan Luchian, who masterfully adapted Impressionist and Post-Impressionist principles.

Post-Impressionist Explorations

Sirato’s style naturally evolved towards Post-Impressionism, a movement that, while retaining the bright colors and visible brushstrokes of Impressionism, placed greater emphasis on structure, symbolic content, and personal expression. Artists like Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin had paved the way for this more subjective approach to painting. Sirato, in his Post-Impressionist phase, focused on more solid compositions and a deeper exploration of emotional and psychological states. His portrait Woman Reading is a fine example, where the artist moves beyond mere representation to capture the introspective mood and focused concentration of the subject. The careful construction of form and the expressive use of color are characteristic of this period.

Symbolist Undertones

Symbolism also found a resonant chord in Sirato's artistic temperament. This late 19th-century movement, which emphasized dreams, spirituality, and the evocative power of symbols, offered artists a way to explore inner worlds and abstract ideas. Sirato's painting Millefiori is a notable work in this vein. The title itself, meaning "a thousand flowers," suggests a decorative richness, but the painting transcends mere ornamentation. It embodies a poetic and emotional expression, exploring the symbolic relationship between humanity and the natural world through a harmonious and balanced composition, rich in color and suggestive forms. This interest in the symbolic and the poetic connected him to a broader European Symbolist current, which had also influenced Romanian artists like Dimitrie Paciurea in sculpture.

Forays into Expressionism

While not his dominant mode, Sirato also experimented with elements of Expressionism. This movement, characterized by its use of distorted forms, intense colors, and a focus on conveying subjective emotion, often with a critical edge, aligned with Sirato's own inclination towards social commentary. In some of his works, particularly those with a satirical or critical intent, one can observe an exaggeration of color and form designed to heighten the expressive impact and convey his critique of societal mores or political events. This was a path also explored by contemporaries in Romania who were responding to the intense emotional and social currents of the era.

Key Themes and Subjects

Throughout his diverse stylistic explorations, certain themes and subjects recurred in Francisc Sirato's oeuvre, reflecting his artistic concerns and his engagement with the world around him.

Social and Political Commentary

From his early career as a graphic artist and caricaturist, Sirato maintained a strong interest in social and political critique. His satirical drawings were pointed and often humorous, but they carried serious undertones, addressing issues of inequality, corruption, and the impact of war and political instability. Even in his paintings, this critical spirit often surfaced, sometimes subtly through the depiction of character or more overtly in works that directly referenced contemporary events. He used masks and clown figures, traditional motifs for social satire, to comment on the follies and hypocrisies he observed.

Still Lifes: The Poetry of the Mundane

Sirato was a master of the still life genre. His compositions, whether featuring flowers, fruit, or everyday objects, were never mere academic exercises. He imbued them with a sense of life and a profound appreciation for the beauty of the ordinary. Works like Still Life with Vase and Roses, Still Life with Fruit (1930), and Still Life with Red Card and Carrots (1943-1946) demonstrate his exceptional ability to harmonize colors, capture textures, and create compositions that are both visually pleasing and emotionally resonant. He explored the interplay of light and shadow, the vibrancy of color, and the tactile qualities of objects, transforming simple arrangements into poetic meditations on form and existence. His approach to still life can be compared to that of other modern masters like Henri Matisse or Giorgio Morandi, who also found deep expressive potential in this genre.

Portraits and Figure Studies

Portraits and figure studies formed another significant part of Sirato's work. He was interested in capturing not just the physical likeness of his subjects but also their inner character and psychological state. Woman Reading is a prime example of his ability to convey introspection and quiet emotion. His figures are often rendered with a sensitivity that speaks to his humanist concerns. Whether depicting anonymous individuals or specific personalities, Sirato sought to reveal the human condition through his portrayals. His work in this area can be seen in the context of other Romanian portraitists like Corneliu Baba, though Sirato's style remained more aligned with Post-Impressionist aesthetics.

Landscapes: Capturing Light and Atmosphere

While perhaps less prolific in landscape painting compared to still lifes, Sirato's landscapes are notable for their atmospheric quality and their sophisticated handling of light and color. Colentina Landscape is a particularly striking example. In this work, Sirato employs a lowered horizon line and enhances the forms of the trees to create a sense of expansive, almost infinite space. The interplay of light and shadow, and the carefully chosen palette, contribute to a beauty that verges on the surreal, demonstrating his ability to transform a natural scene into a highly personal and evocative vision. This approach to landscape, focusing on subjective experience and atmospheric effect, aligns with the broader Post-Impressionist reinterpretation of the genre.

Representative Masterpieces

Several works stand out in Francisc Sirato's oeuvre, encapsulating his artistic vision and technical skill.

Colentina Landscape: This painting is celebrated for its innovative composition and its almost dreamlike atmosphere. By manipulating the horizon and the scale of natural elements, Sirato creates a powerful sense of depth and an ethereal quality. The treatment of light is particularly masterful, imbuing the scene with a unique, almost otherworldly beauty that transcends straightforward representation.

Still Life with Vase and Roses: A testament to his Impressionistic phase, this work showcases Sirato's delicate touch and his keen observation of the effects of light on flowers and a vase. The brushwork is lively, and the colors are fresh and vibrant, capturing the ephemeral beauty of the blooms. It reflects a deep appreciation for the simple elegance of nature.

Millefiori: This Symbolist-inspired painting is a rich tapestry of color and form. It moves beyond the purely decorative, using the motif of "a thousand flowers" to explore deeper symbolic meanings related to nature, life, and perhaps the interconnectedness of all things. The balanced composition and the harmonious, almost jewel-like colors create a work of poetic intensity.

Woman Reading: A quintessential example of his Post-Impressionist portraiture, this painting captures a moment of quiet introspection. Sirato focuses on the emotional state of the subject, her absorption in the act of reading conveyed through her posture and the subtle expression on her face. The solid forms and expressive use of color are characteristic of his mature style.

Lila în interior (Lila Indoors): Exhibited in 1923, this painting garnered significant attention at the time. While specific details of its content might require further art historical research for a full description, its mention as a notable work indicates its importance in establishing Sirato's reputation during a key period of his career. It likely showcased his evolving synthesis of modern artistic principles.

Dimensionism: A Revolutionary Concept

Beyond his achievements as a painter and graphic artist, Francisc Sirato was also an art theorist who sought to push the boundaries of artistic expression. In 1936, he was a key figure in launching the "Dimensionist Manifesto" in Paris. This was a significant, if not widely adopted, avant-garde initiative that attempted to bridge the gap between art and the rapidly advancing scientific understanding of the universe, particularly Einstein's theories of relativity and the concept of a four-dimensional spacetime continuum.

The Dimensionist Manifesto, signed by a number of international artists including Alexander Calder, Marcel Duchamp, Joan Miró, and Wassily Kandinsky, called for art to conquer new dimensions. It proposed a progression: literature leaving the line for the plane, painting leaving the plane for space (e.g., Cubism, Futurism, Surrealist objects), and sculpture evolving into "hollowed-out" forms and mobiles that incorporated actual movement and, by implication, time (the fourth dimension).

Sirato's involvement underscored his intellectual engagement with the most advanced ideas of his time. Dimensionism advocated for an art that was not confined to traditional two or three-dimensional representations but could explore non-Euclidean geometries and the integration of time and space. It was a call for artists to create new realities and spiritual experiences, reflecting the changing perception of the world brought about by scientific discoveries. While Dimensionism as a formal movement did not achieve the lasting impact of Cubism or Surrealism, it remains a fascinating example of the early 20th-century avant-garde's desire to revolutionize art in response to a new worldview. For Sirato, it represented a bold attempt to theorize a future for art that was dynamic, multi-dimensional, and intellectually rigorous.

Sirato as an Art Critic and Theorist

Francisc Sirato's intellectual contributions extended to his work as an art critic. He wrote extensively on art, offering insightful analyses of contemporary trends and historical movements. His critical writings, like his theoretical work on Dimensionism, demonstrated a deep understanding of art history and a forward-looking perspective. He was keen to promote modern art in Romania and to foster a greater understanding of its principles among the public and fellow artists.

His role as a critic was not separate from his artistic practice; rather, they informed each other. His understanding of form, color, and composition, honed through his own painting, gave his critiques a practical grounding. Conversely, his theoretical explorations and his engagement with the ideas of other artists and thinkers enriched his own creative output. He championed artists he believed were making significant contributions and was not afraid to challenge conventional artistic notions.

Engagement with Contemporaries and Artistic Circles

Francisc Sirato was an active participant in the Romanian art scene and maintained connections with many of its leading figures. His collaborations and associations played an important role in the development of modern art in the country.

One of the most significant of these was his involvement in "Grupul celor patru" (The Group of Four). Formed in 1926, this influential group, alongside Sirato, included Nicolae Tonitza, a master of color and portraiture with a distinctive lyrical style; Ștefan Dimitrescu, known for his depictions of peasant life and his strong drawing skills; and Oscar Han, a prominent sculptor whose work often explored monumental and symbolic themes. "Grupul celor patru" was a vital force in Romanian art during the interwar period, organizing exhibitions and promoting a vision of modern art that was both contemporary in its language and rooted in Romanian cultural identity. Their collective efforts helped to shape the direction of art in Romania, moving it away from academicism towards more personal and expressive forms.

Sirato's interactions extended beyond this core group. He was influenced by, and in turn influenced, artists like Iosif Iser, whose early guidance was crucial, and Camil Ressu, another major figure in 20th-century Romanian art known for his robust drawing and depictions of rural life. He also maintained contact with artists like Petre Iorgulescu-Yor (often cited as Petre Pascu in some contexts, though Yor is more established) and Cornel Dimpirețescu, sharing an interest in European artistic developments.

His awareness of international art is evident in his work, which shows an understanding of French art in particular. The influence of artists like Henri Matisse, with his bold use of color and decorative line, can be discerned in aspects of Sirato's painting. This engagement with broader European trends, combined with a commitment to the local art scene, characterized Sirato's position within Romanian art. He was both a conduit for international ideas and a shaper of a distinctly Romanian modernism.

Role at the National Museum of Art

Francisc Sirato's contributions to Romanian art were not limited to his personal artistic output and theoretical work. He also played an important institutional role, notably serving as a director or in a significant capacity at the Romanian National Museum of Art (then known under different names, such as the Aman Museum or later, part of the Carol I Foundation collections that would form the National Museum). During his tenure, he articulated a clear vision for the museum's mission, particularly concerning the study and presentation of Romanian national art.

He collaborated with figures like Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaș, a prominent art historian and ethnographer, on defining the specific characteristics of Romanian folk art and its relationship to fine art. Sirato emphasized the importance of scientifically studying ethnographic collections to understand the unique elements of style, form, and color that shaped the nation's artistic expression. He believed that these traditional elements were vital in understanding the "typicality" of Romanian art. This perspective highlighted a desire to connect contemporary artistic creation with the deep roots of national cultural heritage, a common concern among many artists and intellectuals in Central and Eastern Europe during this period of nation-building and cultural self-definition. His work at the museum thus contributed to the codification and valorization of Romanian art history.

Later Years and Legacy

In the 1940s, Francisc Sirato faced financial difficulties, which reportedly led him to cease publishing his graphic works. However, he continued to create art and, for a time, worked at the Bucharest Municipal Library. This position, perhaps undertaken out of necessity, also allowed him to remain immersed in the cultural life of the city and to continue observing the social realities that had always informed his work, especially during the challenging years of World War II and its aftermath.

Despite any personal hardships, Sirato's artistic output continued, and his reputation as a significant modern artist grew. Posthumously, his work has been celebrated in numerous exhibitions, including a major retrospective in 1965 simply titled "Francisc Sirato," which helped to solidify his place in the canon of Romanian art. His paintings are held in major collections, most notably the National Museum of Art of Romania in Bucharest, as well as in private collections.

The legacy of Francisc Sirato is multifaceted. He is remembered as a skilled painter who masterfully navigated the currents of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Symbolism, creating works of enduring beauty and emotional depth. His still lifes, portraits, and landscapes are admired for their sophisticated use of color, light, and composition. He was also a pioneering graphic artist and a sharp social commentator, whose satirical works provided a critical lens on his times.

Furthermore, his role as an art theorist, particularly his involvement with the Dimensionist Manifesto, marks him as an artist with a keen intellectual curiosity and a desire to push the boundaries of artistic thought. His contributions as an art critic and his work in museum leadership further underscore his commitment to the development and understanding of art in Romania.

While some of his more radical ideas, like those presented in the Dimensionist Manifesto, might have been considered controversial or ahead of their time, they demonstrate his engagement with the avant-garde spirit of the early 20th century. His socially critical works, too, may have ruffled feathers among conservative elements, but they attest to his courage and his belief in art's power to reflect and comment on society.

Conclusion

Francisc Sirato was more than just a painter; he was an artist-intellectual who played a dynamic role in the cultural life of Romania for nearly half a century. His journey from satirical graphic artist to a master of Post-Impressionist painting, and from a keen observer of social realities to a bold theorist of new artistic dimensions, reveals a complex and evolving creative spirit. He successfully synthesized international artistic innovations with a personal vision, contributing significantly to the richness and diversity of Romanian modern art. His engagement with contemporaries like Nicolae Tonitza, Ștefan Dimitrescu, Oscar Han, Camil Ressu, and Iosif Iser, and his awareness of international figures like Henri Matisse, placed him at the heart of a vibrant artistic dialogue. Today, Francisc Sirato is recognized as one of Romania's foremost modern artists, whose work continues to be appreciated for its aesthetic quality, its intellectual depth, and its insightful reflection of a transformative era. His legacy endures in his captivating artworks and in his contributions to the theoretical and institutional framework of Romanian art.