The annals of art history are replete with celebrated masters whose lives and works have been meticulously documented and analyzed. Yet, alongside these luminaries exist countless artists whose contributions, while perhaps modest or localized, form part of the intricate tapestry of creative production in their time. François Adolphe Grison appears to belong to this latter category – a figure whose presence is confirmed by tangible evidence, yet whose life story and artistic footprint remain largely shrouded in mystery. Reconstructing his career requires piecing together fragments of information and placing him within the vibrant, complex art world of what was likely 19th-century France.

Our understanding of François Adolphe Grison hinges significantly on sparse documentation. Unlike contemporaries such as Claude Monet or Edgar Degas, whose activities were often noted in the press or personal correspondences, Grison lacks a detailed biographical record in readily accessible sources. Key information, including his precise dates of birth and death, his place of origin, and his formal artistic training, remains elusive. This scarcity challenges art historians seeking to fully appreciate his work and its context.

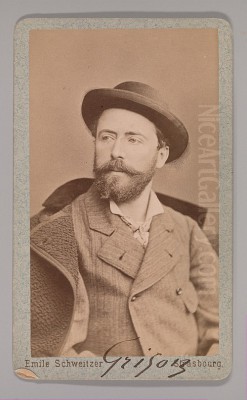

The Tangible Evidence: The Bookworm

The most concrete piece of evidence confirming François Adolphe Grison's existence as a painter is a specific artwork: an oil painting titled The Bookworm. Records indicate this work measures 8 1/2 by 6 1/4 inches (approximately 21.6 x 15.9 cm), a relatively intimate scale often favored for genre scenes or detailed studies. Crucially, the painting is noted as being signed by the artist, typically in the upper left corner, affirming his authorship.

The title, The Bookworm, immediately suggests a genre scene, a popular category in the 19th century. Such paintings often depicted everyday life, historical vignettes, or character studies. A "bookworm" theme typically involves a figure engrossed in reading or surrounded by books, often an elderly scholar, an antiquarian, or a dedicated student within a detailed interior setting. Artists like Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier excelled in such meticulously rendered small-scale historical genre scenes, capturing textures and details with incredible precision. While we lack a visual description of Grison's painting, the title alone places it within this popular tradition.

Further information reveals that Grison's The Bookworm was involved in a charity auction benefiting the Brooklyn Museum. This detail, while not providing insight into the painting's creation, indicates that the work circulated, possessed monetary or artistic value recognized by collectors or donors, and became associated, even if tangentially, with a significant cultural institution. It suggests the painting was appreciated enough to be used for philanthropic purposes, hinting at a certain level of quality or appeal. However, without more examples of his work, The Bookworm remains an isolated data point, making broad conclusions about his overall style or thematic concerns difficult.

Navigating the Historical Record: Identity and Scarcity

The challenge in researching François Adolphe Grison is compounded by the potential for confusion with other individuals bearing similar names. Historical records, particularly from periods with less standardized record-keeping, can be ambiguous. The provided source materials highlight this very issue, mentioning several individuals named "Grison" or "Adolphe Grison" in contexts unrelated to painting.

For instance, references exist to an Emmanuel Grison's father, simply named "Grison," involved in French history. Another mention concerns an "Grison (Adolphe)" who received an honorific medal, possibly for artistic achievement, but without definitive linkage to François Adolphe Grison the painter. Furthermore, figures like Georges Grison, identified as a 19th-century crime investigator and journalist, and Adolphe Guillot, a judge involved with similar circles, are clearly distinct individuals. Adding to the complexity are mentions of contemporary figures like Aubrey Grison, a French artist and disability rights activist working in photography and painting, and Pierre Grison, an entomologist.

One particularly intriguing, yet ambiguous, piece of information comes from a legal document concerning inheritance law. This document reportedly mentions a "Francois Adolphe Grison" in the context of being disinherited. While this is a specific biographical detail, confirming that this individual is the same person as the painter of The Bookworm is problematic without corroborating evidence. Disinheritance could occur for various reasons, sometimes related to family disputes, societal transgressions, or legal technicalities, as hinted at by general discussions of "emotional abandonment" in legal contexts or specific historical instances like property confiscation during the French Revolution affecting families like the Brissacs. However, applying these general possibilities directly to the painter Grison remains speculative.

This proliferation of similar names across different fields and contexts underscores the need for caution. It highlights how easily identities can be conflated when dealing with figures who did not achieve widespread, lasting fame. Establishing the painter's specific life events requires careful verification against primary sources, a task made difficult by the apparent lack of such readily available documentation for François Adolphe Grison.

Situating Grison: The Landscape of 19th-Century French Art

Assuming François Adolphe Grison was active during the 19th century, likely in France given his name and the context of related mentions, his work would have been created amidst a period of extraordinary artistic ferment and transformation. The French art world was a dynamic arena characterized by competing styles, powerful institutions, and revolutionary movements that challenged the status quo. Understanding this landscape helps contextualize the potential environment in which Grison worked, even if his specific allegiances remain unknown.

The dominant force for much of the century was Academic art, championed by the École des Beaux-Arts and showcased at the official Paris Salon. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, and Alexandre Cabanel achieved immense success with their highly polished, technically brilliant paintings, often depicting historical, mythological, or allegorical subjects. Their work represented the established taste, emphasizing draftsmanship, idealized forms, and smooth finishes. The Salon was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition, attract patrons, and build careers.

However, the 19th century was also defined by reactions against Academicism. Realism emerged forcefully mid-century, led by Gustave Courbet, who famously declared he would paint only what he could see. Courbet, along with Jean-François Millet, focused on depicting the unvarnished realities of peasant life and labor, challenging the idealized conventions of the Academy. Their work was often seen as politically charged and aesthetically radical.

Simultaneously, landscape painting gained new prominence with the Barbizon School. Artists like Théodore Rousseau and Camille Corot painted directly from nature in the Forest of Fontainebleau, seeking a more truthful and less formalized representation of the natural world, paving the way for later movements.

The latter half of the century witnessed the revolutionary impact of Impressionism. Figures such as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Berthe Morisot broke dramatically with tradition. They prioritized capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and atmosphere, and scenes of modern life, using broken brushwork and a brighter palette. Their independent exhibitions, starting in 1874, directly challenged the hegemony of the Salon.

Alongside these major movements, genre painting continued to flourish, catering to a bourgeois market interested in narrative scenes, historical anecdotes, and detailed depictions of interiors or specific character types. Artists like James Tissot captured elegant social life, while others like Jehan Georges Vibert specialized in satirical scenes, often involving clergy. The meticulous detail of Meissonier remained highly prized by many collectors throughout the period. Furthermore, Symbolism, represented by artists like Gustave Moreau, offered an alternative path, exploring mystical themes and subjective states. Édouard Manet, a pivotal figure, bridged Realism and Impressionism, influencing generations with his bold technique and modern subjects.

It is within this rich and varied artistic milieu that François Adolphe Grison likely operated. His choice of subject in The Bookworm aligns well with the enduring popularity of genre painting, a field that accommodated a wide range of styles, from the highly detailed Academic approach to potentially looser, more character-focused interpretations.

Artistic Style: Speculation and Context

Defining the artistic style of François Adolphe Grison based solely on the title and dimensions of The Bookworm is inherently speculative. However, we can consider possibilities based on the context of 19th-century genre painting. If Grison aimed for commercial success or academic recognition, his style might have leaned towards the meticulous detail and smooth finish favored by the Salon and collectors who admired Meissonier or Gérôme. Such an approach would involve careful drawing, subtle modeling of form, and attention to the textures of fabrics, wood, and paper within the scholar's study.

Alternatively, his style could have been somewhat looser, perhaps influenced by Realist principles, focusing more on the character and mood of the scene rather than microscopic detail. The small scale of the painting (8 1/2 x 6 1/4 inches) often lent itself to detailed work, but could also accommodate more intimate, less formal character studies. Without seeing the painting, it's impossible to say whether his handling of paint was tight and controlled or showed more visible brushwork.

The lack of information regarding Grison's training is a significant gap. Was he a product of the École des Beaux-Arts or a regional academy? Did he study under a known master? Or was he largely self-taught? Each path would likely influence his stylistic choices and technical approach. Similarly, the absence of any record linking him to specific artistic collaborators, students, or mentors prevents us from placing him within a direct lineage or circle of influence. We don't know if he exhibited at the Paris Salon, regional exhibitions, or primarily sold through dealers.

His relationship to the major movements of his time is equally unclear. Does The Bookworm show any awareness of Realism's earthiness, or Impressionism's focus on light and modern life? Given the subject matter, it seems more likely to fall within the broad categories of Academic genre painting or perhaps a form of historical Realism, but this remains conjecture. The painting could be a competent, conventional work typical of many artists of the period, or it could possess unique qualities that are simply lost to us without visual access or further documentation.

The Enigma of Legacy: Critical Reception and Influence

Just as biographical details and stylistic analysis remain elusive, so too does any assessment of François Adolphe Grison's contemporary reception or lasting influence. There is no readily available evidence of critical reviews of his work in 19th-century journals or newspapers. Major art critics of the era, such as Charles Baudelaire, Théophile Thoré-Bürger, or later, Gustave Geffroy, documented and debated the merits of countless artists, shaping public opinion and contributing to the historical record. Grison does not appear to feature in these prominent discussions.

Furthermore, there is no indication that Grison was associated with any specific artistic group, society, or movement. Unlike the Impressionists who banded together for independent exhibitions, or the Barbizon painters with their shared focus, Grison seems to have operated outside of these documented circles. This lack of affiliation makes it harder to trace his impact or connections within the art world.

Consequently, François Adolphe Grison's historical influence appears negligible based on current knowledge. He did not demonstrably shape the direction of art, inspire a following, or contribute significantly to the major stylistic shifts of the 19th century in the way that figures like Courbet, Manet, or Monet did. His legacy, as it stands, is confined to the existence of at least one painting, The Bookworm, and the fragmented, ambiguous mentions in historical and legal records.

He likely represents a common phenomenon in art history: the competent professional artist who achieved some measure of success or production in their own time but whose work did not attain the level of innovation, fame, or critical acclaim necessary to secure a prominent place in subsequent historical narratives. Many artists exhibited at the Salon or sold works privately without ever entering the canon of "great masters." Their stories often require dedicated archival research to uncover.

Conclusion: A Painter Shrouded in Mystery

François Adolphe Grison remains an enigmatic figure in the landscape of 19th-century art. Confirmed as a painter through the existence of his work The Bookworm and its documented provenance via a charity auction, his life story is otherwise a collection of uncertainties and potential misidentifications. The tantalizing mention in a legal document regarding disinheritance adds a layer of human drama, but its connection to the artist cannot be definitively established. The confusion with other individuals named Grison active in different fields further complicates the research process.

While we can situate him broadly within the rich artistic context of 19th-century France – an era of Academic dominance, Realist rebellion, Impressionist revolution, and the flourishing of genre painting – his specific place within this milieu is unknown. We lack the information to firmly define his style, identify his teachers or associates, or assess his contemporary reception and influence. He stands as a reminder of the vast number of artists whose careers unfolded alongside the celebrated names we know today, contributing to the artistic fabric of their time in ways that are not always fully recorded or remembered.

The study of figures like François Adolphe Grison highlights the limitations of art historical knowledge and the challenges of reconstructing the past, particularly for those who operated outside the circles of major fame or controversy. Yet, acknowledging these obscurer figures is essential for a complete understanding of art history, recognizing the breadth and depth of creative activity in any given period. François Adolphe Grison, the painter of The Bookworm, remains a subject awaiting potential future discoveries in archives, collections, or forgotten documents that might one day shed more light on his life and work. Until then, he persists as a name attached to a single known painting, a whisper from a bygone artistic era.