Léon-François-Antoine Fleury stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French landscape painting. Born in Paris on December 18, 1804, and passing away in the same city on November 11, 1858, Fleury's career spanned a period of significant artistic evolution, witnessing the shift from Neoclassical ideals towards a more naturalistic and ultimately Realist depiction of the world. His work, characterized by a sensitivity to light and a dedication to capturing the essence of the French and Italian countryside, places him as a contemporary and peer to some of the era's most influential artists.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Léon-François-Antoine Fleury was immersed in the world of art from his very beginnings. His father, Antoine-Claude Fleury (1774-1824), was himself a painter, specializing in portraiture and genre scenes. This familial connection undoubtedly provided young Léon with his initial exposure to artistic techniques and the life of an artist. Under his father's tutelage, he would have learned the foundational skills of drawing and painting, an apprenticeship common for aspiring artists of the time.

Seeking more formal training, Fleury enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1821. This institution was the bastion of academic art in France, emphasizing rigorous training in drawing from classical sculpture and the live model, as well as the study of historical and mythological subjects. At the École, Fleury became a student of Louis Hersent (1777-1860), a respected painter of historical subjects and portraits who had himself been a pupil of Jean-Baptiste Regnault. Hersent's instruction would have reinforced the academic principles of composition, form, and idealized beauty.

However, it was perhaps his subsequent studies that more decisively shaped his direction as a landscape painter. Fleury joined the studio of Jean-Victor Bertin (1767-1842), a pivotal figure in the development of French landscape painting. Bertin, while rooted in the classical tradition of historical landscape epitomized by artists like Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes (1750-1819), encouraged his students to study nature directly. Valenciennes himself had advocated for outdoor sketching, a practice that would become central to the next generation.

The Influence of Bertin's Studio and Camille Corot

Jean-Victor Bertin's studio was a vibrant hub for aspiring landscape painters. It was here that Fleury encountered several artists who would become significant figures in their own right, most notably Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875). Corot, who also studied with Bertin, would go on to become one of the most beloved and influential landscape painters of the 19th century, a leading member of the Barbizon School and a precursor to Impressionism.

The camaraderie and shared learning environment in Bertin's studio were crucial. Artists would often sketch together, critique each other's work, and absorb the evolving ideas about landscape painting. While Bertin maintained a degree of Neoclassical structure in his finished compositions, his emphasis on direct observation of nature laid the groundwork for a more naturalistic approach. Fleury, alongside Corot and others like Achille-Etna Michallon (1796-1822), another brilliant student of Bertin who died tragically young but had already won the Prix de Rome for historical landscape, would have participated in sketching trips in the environs of Paris, honing their ability to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere.

Corot's influence on his peers, including Fleury, cannot be overstated. Corot’s own journey towards a more lyrical and personal interpretation of nature, his mastery of tonal values, and his dedication to plein-air (open-air) sketching provided a powerful example. While Fleury developed his own distinct style, the shared experiences and artistic dialogues from this period were formative.

Travels and the Italian Sojourn: Deepening Naturalism

Like many artists of his generation, Fleury understood the importance of travel, particularly to Italy, which had long been considered an essential part of an artist's education. The Roman Campagna, with its picturesque ruins, umbrella pines, and unique quality of light, had attracted landscape painters for centuries, from Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) and Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) to his own contemporaries.

Fleury undertook sketching tours not only within France, exploring regions like Normandy, the Auvergne, and the Forest of Fontainebleau (the eventual heart of the Barbizon School), but also ventured into neighboring countries and, significantly, to Italy. These journeys provided him with a wealth of motifs and a deeper understanding of varied landscapes and atmospheric conditions. His Italian studies, in particular, allowed him to refine his ability to render light and shadow, and to imbue his scenes with a sense of place.

His dedication to working directly from nature is evident in the freshness and immediacy of many of his studies. This practice of creating oil sketches outdoors was becoming increasingly common, allowing artists to capture the transient effects of weather and light with greater accuracy than was possible in the studio. These studies would then often serve as a basis for more finished Salon paintings.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

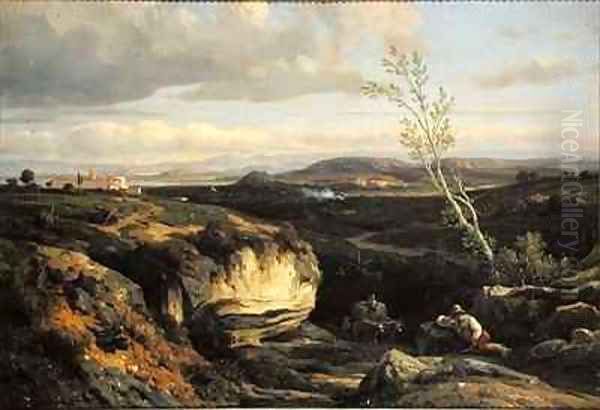

Léon-François-Antoine Fleury's artistic style can be characterized as a blend of classical compositional structure with an increasing commitment to naturalistic observation. He was particularly adept at capturing the nuances of light and atmosphere, a skill honed through his extensive plein-air work. His landscapes often depict tranquil, bucolic scenes, featuring rivers, mills, forests, and distant hills, rendered with a careful attention to detail and a harmonious palette.

While he did not entirely abandon the picturesque elements favored by earlier landscape traditions, his work shows a move away from the idealized, often mythological, landscapes of the strict Neoclassical school. Instead, Fleury sought to convey the specific character of the locations he painted. His brushwork, while generally controlled, could also exhibit a certain freedom, especially in his studies, reflecting the directness of his engagement with the subject.

His paintings often evoke a sense of peace and harmony with nature. He was interested in the interplay of light on foliage, the reflection of skies in water, and the gentle undulation of the terrain. While figures sometimes populate his landscapes, they are usually small and integrated into the scene, serving to animate it rather than being the primary focus, a common trait in the evolving landscape genre of the period.

Representative Works

Throughout his career, Fleury produced a significant body of work, exhibiting regularly at the Paris Salon. Some of his notable paintings help illustrate his artistic concerns and development:

One of his well-regarded pieces is "View of Tivoli, from Santa Maria del Giglio." Tivoli, near Rome, was a classic subject for landscape painters, famed for its waterfalls, ancient ruins, and dramatic scenery. Fleury’s interpretation would have balanced the picturesque qualities of the site with his naturalistic approach to light and atmosphere.

"The Allier at Vichy, after an Inundation" showcases his interest in specific French locales and the effects of natural phenomena. Depicting the aftermath of a flood would have allowed him to explore unusual light conditions, reflections, and the altered state of the landscape, appealing to the Romantic sensibility for nature's power, yet rendered with his characteristic observational care.

Works like "A Mill at Aunay" and "A Mill near Quiberville" (likely Quiberville in Normandy) highlight his fondness for rural, man-altered landscapes. Mills were a popular motif, symbolizing a harmonious relationship between human activity and the natural world, and offering interesting compositional possibilities with their structures and water features.

A series titled "The Four Seasons" would have allowed Fleury to explore the changing character of the landscape throughout the year, a theme that challenged artists to capture different palettes, light conditions, and atmospheric effects, demonstrating his versatility and deep observation of nature's cycles.

His broader category of "Italian Landscape" paintings would encompass the numerous studies and finished works derived from his travels south, reflecting the profound impact of the Italian light and scenery on his artistic vision. These works often possess a clarity and warmth characteristic of the Mediterranean environment.

Navigating the Paris Salon and Recognition

The Paris Salon was the most important public art exhibition in the Western world during the 19th century. Success at the Salon could make an artist's career, leading to sales, commissions, and official recognition. Fleury was a regular exhibitor, and his work received positive attention.

He was awarded a third-class medal at the Salon of 1837, a significant acknowledgment of his talent and contribution. This was followed by an even more prestigious first-class medal in 1845. These awards indicate that his work was well-received by the Salon juries, which, while often conservative, were gradually becoming more accepting of landscape painting as a serious genre in its own right, moving beyond its traditional subservient role to historical painting.

Fleury's ability to gain recognition at the Salon suggests that his style struck a balance between innovation and tradition. His solid academic grounding, combined with his fresh, naturalistic approach, likely appealed to a broader audience and a segment of the critical establishment. He was seen as an artist who was pushing the boundaries of landscape painting without radically overturning established conventions, a path also trod by Corot in his earlier Salon entries.

Fleury in the Context of 19th-Century French Landscape Painting

To fully appreciate Léon-François-Antoine Fleury, it's essential to place him within the dynamic artistic currents of his time. The first half of the 19th century was a period of profound change in French landscape painting. The Neoclassical tradition, with its emphasis on idealized, historical landscapes as practiced by artists like Valenciennes and Bertin, was gradually giving way to a more Romantic and, subsequently, naturalistic vision.

Artists of the Romantic movement, such as Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) and Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), while primarily known for other genres, also brought a new emotional intensity and dynamism to their depictions of nature when they did engage with landscape. This Romantic sensibility influenced the way landscapes were perceived and painted, emphasizing nature's power and sublime beauty.

Fleury's career coincided with the rise of the Barbizon School, a group of painters who gathered in the village of Barbizon, near the Forest of Fontainebleau, to paint directly from nature. Key figures included Théodore Rousseau (1812-1867), Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), Charles-François Daubigny (1817-1878), Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña (1807-1876), Constant Troyon (1810-1865), and Jules Dupré (1811-1889), alongside Corot. While Fleury may not have been a formal member of this group, his commitment to plein-air painting and his naturalistic style aligned closely with their ideals. He shared their desire to capture the authentic character of the French countryside.

Daubigny, for instance, famously used a studio boat, the "Botin," to paint river scenes directly from the water, pushing the boundaries of plein-air practice. Rousseau was a meticulous observer of trees and forest interiors, striving for a profound fidelity to nature. Millet focused on peasant life within the landscape, imbuing his scenes with a sense of dignity and realism. Fleury's work, while perhaps less overtly programmatic than some Barbizon painters, contributed to this broader shift towards a more truthful and less idealized representation of nature.

Later in Fleury's life, Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) emerged as the leading figure of the Realist movement, advocating for an art that depicted the world and contemporary life without idealization or sentimentality. Courbet's bold, often confrontational, approach to painting, including his landscapes, further challenged academic conventions. While Fleury's style was generally more gentle and picturesque than Courbet's rugged Realism, both artists shared a commitment to observing and representing the tangible world.

Relationship with Contemporaries

Fleury's most significant documented artistic relationship was with Camille Corot, forged in Bertin's studio. This was a period of mutual learning and influence. It's known that Corot sometimes painted figures into the landscapes of his friends, a collaborative practice not uncommon at the time. It is plausible that such collaborations might have occurred with Fleury, though specific instances are not always well-documented. Their shared experiences in Italy and their dedication to capturing the subtleties of light and atmosphere created a strong artistic kinship.

Regarding Gustave Courbet, while both were active landscape painters, and there is some suggestion they might have been on a painting trip in Rome around the same time, the extent of any direct personal or artistic interaction remains unclear. Courbet's path was more radical, and his social and political views often set him apart.

Fleury would also have been aware of, and likely interacted with, other landscape painters active in Paris and exhibiting at the Salon. These would include artists like Paul Huet (1803-1869), a Romantic landscapist known for his dramatic depictions of nature, and Prosper Marilhat (1811-1847), famed for his Orientalist landscapes. The Parisian art world was relatively compact, and artists frequently crossed paths at studios, exhibitions, and art supply shops. Edouard Bertin (1797-1871), Jean-Victor's brother and also a landscape painter, was another contemporary from that circle.

The influence of earlier masters like the Dutch Golden Age landscape painters, such as Jacob van Ruisdael (c. 1629-1682) and Meindert Hobbema (1638-1709), was also pervasive, admired for their naturalism and attention to atmospheric effects. These historical precedents informed the work of many 19th-century French landscapists, including Fleury.

Legacy and Influence

Léon-François-Antoine Fleury did not achieve the towering fame of a Corot or a Courbet, nor did he lead a distinct school or movement. However, his contribution to French landscape painting is significant. He was a dedicated and skilled artist who played a part in the transition from Neoclassical landscape to a more naturalistic and observational approach.

While there is no specific record of Fleury having formal students who went on to achieve great fame, his work, regularly exhibited at the Salon and admired for its qualities, would have been seen by countless younger artists. His dedication to plein-air painting and his sensitive rendering of light and atmosphere contributed to the evolving visual language of landscape art. He was part of a generation that collectively paved the way for the Impressionists, who would take the principles of outdoor painting and the study of light to even more radical conclusions later in the century. Artists like Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) built upon the foundations laid by Fleury's generation.

His paintings remain in various public and private collections, valued for their charm, their technical skill, and their representation of a particular moment in the history of art. They offer a window into the French and Italian countryside as seen through the eyes of a dedicated observer, an artist who found beauty and meaning in the faithful depiction of the natural world.

Conclusion

Léon-François-Antoine Fleury was a talented and respected landscape painter whose career unfolded during a pivotal era in French art. Trained in the academic tradition but responsive to the growing call for naturalism, he forged a style characterized by careful observation, a nuanced understanding of light, and a deep appreciation for the landscapes he depicted. His association with Jean-Victor Bertin and Camille Corot placed him at the heart of important developments in landscape painting.

Through his travels, his diligent plein-air practice, and his consistent presence at the Paris Salon, Fleury contributed to the elevation of landscape painting as a significant genre. While perhaps overshadowed by some of his more revolutionary contemporaries, his work embodies the sincere pursuit of capturing the beauty and truth of nature, earning him a rightful place in the narrative of 19th-century French art. His paintings continue to be admired for their quiet beauty and their skillful evocation of time and place, reflecting an artist deeply connected to the world around him.