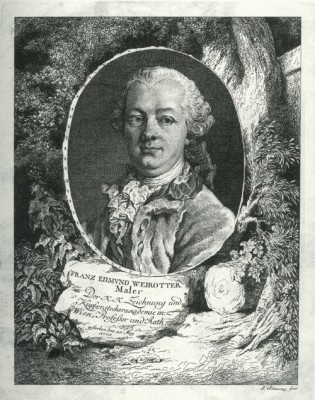

Franz Edmund Weirotter (1733–1771) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes underappreciated, figure in eighteenth-century European art. An Austrian by birth, he distinguished himself primarily as a landscape painter and, more notably, as a prolific and highly skilled etcher. His work, characterized by a sensitive naturalism and a keen eye for picturesque detail, captured the landscapes, rustic scenes, and evocative ruins of his time, leaving behind a legacy that influenced subsequent generations of artists. Though his career was tragically short, spanning less than two decades of active production, Weirotter's output was considerable, and his dedication to the art of etching helped elevate the medium's status.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Innsbruck, the capital of Tyrol in Austria, in 1733, Franz Edmund Weirotter's early artistic inclinations soon led him away from his mountainous homeland. Seeking broader artistic horizons, he journeyed to Paris, then a preeminent center of European art and culture. This move proved pivotal for his development. In Paris, he became a student of the renowned German-born engraver and art dealer Johann Georg Wille (1715–1808).

Wille was a central figure in the Parisian art world, known for his own accomplished engravings and for his influential studio, which attracted aspiring artists from across Europe. Under Wille’s tutelage, Weirotter honed his skills in drawing and, crucially, in the complex techniques of etching. Wille was a proponent of studying directly from nature, a principle that deeply resonated with Weirotter and became a hallmark of his artistic practice. This emphasis on empirical observation set him apart from more formulaic approaches to landscape prevalent at the time.

Weirotter's formative years also included significant travels, most notably to Italy. This journey, a common rite of passage for Northern European artists, exposed him to the classical landscapes and ancient ruins that had inspired artists for centuries. He returned from Italy with a rich portfolio of sketches and drawings, capturing the sun-drenched Italian countryside, its architectural remnants, and the daily life of its inhabitants. These Italian experiences further enriched his visual vocabulary and thematic repertoire, providing him with motifs that would appear in his later etchings.

His time in Rome, in particular, would have brought him into contact, or at least into an awareness, of the work of artists like Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), whose dramatic etchings of Roman antiquities were already famous. While Weirotter’s style was generally more delicate and less monumental than Piranesi's, the Italian master's focus on ruins as subjects of profound artistic and historical interest likely reinforced Weirotter's own inclinations.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

Weirotter’s artistic style is distinguished by its blend of meticulous observation and a graceful, almost lyrical, freedom of line. His etchings are celebrated for their clarity, delicate tonal gradations, and the skillful rendering of light and atmosphere. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the textures of stone, foliage, and water, imbuing his scenes with a tangible sense of place.

A strong current of naturalism runs through his work. Unlike artists who composed idealized or heroic landscapes based on established conventions, Weirotter, following Wille's teachings, grounded his art in the direct study of the world around him. His landscapes feel authentic and immediate, populated by carefully observed figures engaged in everyday activities – peasants working in fields, travelers resting by a roadside, fishermen tending their nets. These figures are rarely the primary subject but serve to animate the scenes and provide a sense of scale and human presence within the broader natural setting.

Ruins were a recurring and significant theme in Weirotter's oeuvre. The eighteenth century witnessed a burgeoning fascination with the picturesque, and crumbling castles, ancient abbeys, and dilapidated farmhouses became favored subjects for artists. Weirotter excelled in depicting these remnants of the past, capturing not only their architectural forms but also their evocative power, hinting at the passage of time and the transience of human endeavors. His ruins are often integrated harmoniously into the landscape, overgrown with vegetation, suggesting a gentle reclamation by nature. This approach differed from the more dramatic or sublime interpretations of ruins favored by some of his contemporaries, leaning instead towards a quieter, more contemplative beauty.

He also demonstrated proficiency in watercolor, a medium often used for preparatory studies or for finished drawings intended as independent works. This facility with watercolor likely informed his etching practice, particularly in achieving subtle tonal variations and atmospheric effects. His works often depict a harmonious coexistence between nature and human activity, reflecting an Enlightenment-era appreciation for the pastoral and the rustic.

The influence of Dutch Golden Age landscape painters, such as Jacob van Ruisdael (c. 1629–1682) or Meindert Hobbema (1638–1709), can be discerned in Weirotter's attention to detail and his focus on the specific character of a place, though filtered through an 18th-century sensibility. Similarly, the work of earlier Dutch etchers like Esaias van de Velde (c. 1587–1630) or Boetius Adamsz. Bolswert (c. 1585–1633), known for their landscape prints, provided a rich tradition upon which Weirotter could draw, even as he developed his own distinct voice.

Key Works and Series

Franz Edmund Weirotter's reputation rests firmly on his extensive body of etchings. Among his most celebrated achievements is the series titled XII Vues de la Normandie (Twelve Views of Normandy). This collection, often cited as a masterpiece of eighteenth-century landscape etching, was created for a patron named Brillon Duperon (sometimes referred to as Brillon de la Croix). The first edition's title plate was published by his former master, Johann Georg Wille, in 1761.

The Normandy series showcases Weirotter's exceptional skill in capturing the diverse scenery of the French region – its charming villages, rustic cottages, ancient fortifications, and coastal views. Each plate is a testament to his meticulous technique and his ability to imbue seemingly ordinary scenes with artistic interest and atmospheric depth. The figures within these landscapes, whether peasants, travelers, or fishermen, are rendered with a lively naturalism that enhances the overall composition.

Beyond the Normandy series, Weirotter produced numerous individual prints and other sets. Works such as Alte Brücke (Old Bridge) and Alte Kirche (Old Church) exemplify his fascination with picturesque architecture and the interplay of man-made structures with the natural environment. These etchings often feature crumbling stonework, overgrown vegetation, and a subtle play of light and shadow that creates a mood of gentle melancholy or quiet contemplation.

Other notable works include Near the Great Harbour at Marseille, which demonstrates his ability to handle more expansive coastal scenes, and genre-like compositions such as Men Arguing on Pieces of the Pond and Busy Village Street. These pieces highlight his keen observation of human interaction and daily life, integrated seamlessly within his landscape settings. Prints like Hunters at a Cave Entrance and Three Travellers in a Crumbling Ruin further underscore his interest in the picturesque and the narrative potential of figures within a landscape.

A significant posthumous collection of his work, Œuvre de F. E. Weirotter, Peintre Allemand, Mort à Vienne en 1771, was published in Paris around 1775 by Pierre-François Basan. This compilation, containing over two hundred etchings, played a crucial role in disseminating his art to a wider audience and cementing his reputation after his untimely death. The sheer volume and consistent quality of the works in this collection attest to his diligence and artistic vision.

His approach to landscape can be seen in dialogue with contemporary French painters like Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714–1789), known for his seascapes and landscapes that often balanced topographical accuracy with picturesque elements, or Hubert Robert (1733–1808), a close contemporary dubbed "Robert des Ruines" for his romantic depictions of ancient ruins, often imaginatively combined. While Robert's ruins were frequently more grandiose and dramatically staged, both artists shared an interest in the evocative power of architectural decay.

Academic Career and Teaching

After his formative years in Paris and his travels, Franz Edmund Weirotter eventually settled in Vienna. In 1767, his talent and reputation earned him a prestigious appointment as Professor of Landscape Drawing at the Imperial and Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna (Kaiserliche königliche Maler- und Bildhauerakademie, later the Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien).

This position was a significant recognition of his abilities and placed him in a key role for shaping the next generation of landscape artists in the Habsburg capital. As a professor, he would have imparted the principles he had absorbed from Wille and developed through his own practice – particularly the importance of drawing from nature and the meticulous study of light, form, and texture. His own prolific output of etchings would have served as exemplary material for his students.

His tenure at the Vienna Academy, though brief due to his early death, contributed to the growing appreciation for landscape art within the Austrian academic tradition. At this time, landscape was gradually gaining status as a genre, moving beyond its traditional role as mere background for historical or mythological scenes. Artists like Weirotter, through both their artistic production and their teaching, played a part in this elevation.

The artistic environment in Vienna during this period was vibrant, with the Academy serving as a central hub. Weirotter's colleagues and students would have been part of a broader Central European artistic current, looking to both Italian and French models while also developing local characteristics. His presence would have strengthened the printmaking tradition within the Academy.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Weirotter's artistic journey brought him into contact with, or at least into the sphere of influence of, several key figures and artistic currents of his time. His most direct and formative relationship was with Johann Georg Wille. Wille's studio in Paris was a melting pot of international talent. Artists like Jean-Georges Wille (Johann Georg's son, 1760-1807), who also became an engraver, would have been part of this environment, albeit younger. The elder Wille's diary and correspondence provide valuable insights into the Parisian art world, and his comments on Weirotter, though sometimes critical of his character, always acknowledged his artistic talent. For instance, upon hearing of Weirotter's death, Wille reportedly remarked, "Cela me fait de la peine, quoique son caractère moral ne valût rien; mais il avait du talent." (This saddens me, although his moral character was worthless; but he had talent.) This suggests a complex relationship, perhaps one where professional respect coexisted with personal friction.

His connection with Brillon Duperon, the dedicatee of the XII Vues de la Normandie, highlights the importance of patronage in the 18th century. Such series were often commissioned or created with a specific patron in mind, and these relationships could be crucial for an artist's career and financial stability.

In France, Weirotter would have been aware of the work of landscape etchers and painters who shared similar interests. Jean-Louis Desprez (1743–1804), though slightly younger, was another artist who traveled to Italy and became known for his dramatic architectural renderings and ruinscapes, often with a theatrical flair. The general interest in picturesque travel and documentation was also embodied by figures like Jean-Claude Richard, Abbé de Saint-Non (1727–1791). Saint-Non was an amateur artist, antiquarian, and patron who undertook extensive travels, particularly in Italy, and published lavishly illustrated accounts of his journeys, such as the Voyage pittoresque ou Description des royaumes de Naples et de Sicile. Weirotter's detailed and evocative landscapes would have appealed to the same sensibility that appreciated Saint-Non's publications, and indeed, Saint-Non is noted as having had close contact with Weirotter and being influenced by his work.

The Swiss artist and poet Salomon Gessner (1730–1788), a contemporary, was highly influential with his idyllic and pastoral landscape etchings and writings, which enjoyed immense popularity across Europe. Gessner's gentle, often sentimental, vision of nature resonated with the Rococo and early Romantic sensibilities, and while Weirotter's style was generally more grounded in direct observation, the prevailing taste for idyllic landscapes shaped by artists like Gessner formed part of the broader artistic context.

In Italy, beyond Piranesi, the tradition of vedute (view painting), perfected by artists like Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal, 1697–1768) and Francesco Guardi (1712–1793) in Venice, had established landscape and cityscape as highly valued genres. While Weirotter's focus was more on rustic and natural landscapes than urban panoramas, the precision and atmospheric qualities of the vedutisti set a high bar for topographical art.

The Dutch artist Cornelis van Noorde (1731–1795), a close contemporary, was also a prolific draftsman and etcher of landscapes and city views, working in a style that, like Weirotter's, showed a careful attention to detail and local character. Such parallels across different European artistic centers highlight a shared interest in landscape etching during this period.

Reception, Legacy, and Influence

During his lifetime, Franz Edmund Weirotter enjoyed considerable acclaim, particularly for his etchings. His appointment as a professor at the Vienna Academy is a clear indicator of the esteem in which he was held. His prints were sought after by collectors and fellow artists, valued for their technical finesse and their charming, naturalistic depictions of landscapes and ruins. The posthumous publication of his Œuvre further solidified his reputation and ensured the continued accessibility of his work.

His influence extended to his students at the Vienna Academy and to other contemporary artists who admired his approach to landscape. The clarity and delicacy of his etching technique provided a model for aspiring printmakers. His emphasis on direct observation of nature, while not unique to him, contributed to a broader shift towards naturalism in landscape art that would gain further momentum in the following century.

However, despite his contemporary success, Weirotter's fame somewhat receded in the subsequent art historical narrative, perhaps overshadowed by artists who engaged with more grandiose or overtly Romantic themes. Some critics have suggested that the very intimacy and subtlety of his work, its focus on the "minor" beauties of the everyday landscape rather than heroic or sublime vistas, might have led to its being undervalued in periods that prized more monumental artistic statements. There was also a comment from his former teacher, Wille, that suggested a difficult personality, which, while not directly impacting the art's quality, can sometimes color historical reception.

Nevertheless, Weirotter's contribution to eighteenth-century printmaking remains significant. His works are preserved in major print collections worldwide, including the Albertina in Vienna, the British Museum in London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, among many others. These collections attest to his enduring artistic merit. Modern scholarship continues to appreciate his refined technique, his sensitive portrayal of the natural world, and his role in the development of landscape etching. His art offers a window into the aesthetic sensibilities of the mid-eighteenth century, a period of transition between the late Baroque/Rococo and the emerging currents of Neoclassicism and Romanticism.

His dedication to capturing the specific character of the places he depicted, whether in Normandy, Italy, or the environs of Vienna, aligns him with a tradition of topographical accuracy, yet his work is always infused with a picturesque sensibility that elevates it beyond mere documentation. He found beauty in the humble and the decaying, in the quiet corners of the countryside, and in the harmonious interaction of humanity and nature.

Conclusion

Franz Edmund Weirotter's life was short, but his artistic output was rich and influential. As a master etcher, he brought a distinctive blend of Austrian sensibility, Parisian training, and Italian inspiration to the art of landscape. His meticulous yet graceful technique, his commitment to naturalism, and his evocative depictions of rustic scenes and picturesque ruins earned him a distinguished place among eighteenth-century European artists.

His professorship at the Vienna Academy allowed him to pass on his skills and artistic philosophy, contributing to the development of landscape art in Central Europe. While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, Weirotter's delicate and insightful etchings continue to charm and impress those who encounter them, securing his legacy as a significant practitioner of landscape art and a master of the etching needle. His work remains a testament to the enduring appeal of the natural world and the quiet beauty found in its careful observation.