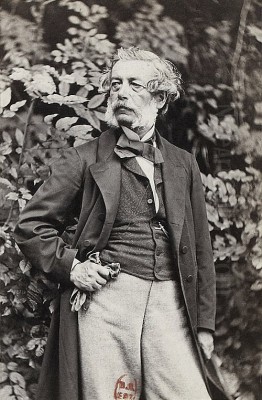

Franz Xaver Winterhalter stands as one of the most prominent and prolific portrait painters of the 19th century. A German artist by birth, he achieved unparalleled international fame through his captivating depictions of European royalty and aristocracy. Operating during a period of significant social and political change, Winterhalter became the favoured visual chronicler of the highest echelons of society, creating images that defined an era and continue to fascinate viewers today. His name became synonymous with elegant, refined, and often dazzlingly luxurious portraiture, securing his place in the annals of art history, particularly as the pre-eminent court painter of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Franz Xaver Winterhalter was born in 1805 in the small village of Menzenschwand, nestled deep within Germany's Black Forest region. His origins were humble; he was born into a peasant family, a background that makes his later ascent to the heights of European court society all the more remarkable. His innate artistic talent, however, did not go unnoticed. Recognizing his potential, support was found to foster his abilities.

A crucial step in his development came with the opportunity to study drawing and engraving. He later secured a scholarship, which enabled him to attend the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich in 1823. In Munich, a major artistic centre, Winterhalter honed his skills in painting and also gained proficiency in lithography, a printmaking technique that would later prove useful in disseminating his popular portraits. Financial support during this period also came from the industrialist Baron von Eichthal.

During his formative years in Munich, Winterhalter had the significant advantage of studying under Joseph Karl Stieler, a renowned portrait painter himself, famous for his "Gallery of Beauties" commissioned by King Ludwig I of Bavaria. Stieler's influence likely reinforced Winterhalter's inclination towards portraiture and provided him with a strong foundation in technique and composition, emphasizing clarity and a certain Neoclassical elegance.

Winterhalter's early career began to take shape in Karlsruhe, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Baden. In 1828, he became the drawing master to Sophie, Grand Duchess of Baden, and by 1834, he was appointed as the court painter to Grand Duke Leopold I of Baden. This position provided him with valuable experience in navigating court circles and fulfilling official commissions, painting portraits of the Grand Ducal family. This early patronage was instrumental in launching his career beyond regional confines.

Rise to Prominence in Paris

Seeking broader horizons and greater opportunities, Winterhalter moved to Paris in 1835. The French capital was then the undisputed centre of the European art world, a vibrant hub teeming with artists, patrons, and competing artistic movements, from the lingering Neoclassicism of masters like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres to the burgeoning Romanticism championed by Eugène Delacroix. Winterhalter arrived at a propitious moment.

His breakthrough in Paris came swiftly, largely thanks to the patronage of King Louis-Philippe I, the "Citizen King" of the July Monarchy. Winterhalter was introduced to the court and soon received commissions to paint the King, Queen Marie Amélie, and their extensive family, the House of Orléans. Between 1838 and 1842, in particular, he was heavily occupied with commissions from the Orléans clan.

These royal portraits, exhibited at the influential Paris Salon, quickly established Winterhalter's reputation. His ability to combine a good likeness with an air of regal elegance and fashionable sensibility struck a chord with the elite. He became known for his flattering portrayals, his meticulous attention to detail in rendering luxurious fabrics and jewels, and his smooth, polished finish. His success in Paris cemented his status as a leading society portraitist.

The favour of the French royal family opened doors across Europe. His name became associated with sophisticated court portraiture, and demand for his work grew exponentially. Paris served as the launching pad for an international career that would see him travel extensively, painting the crowned heads and leading figures of numerous nations.

The International Court Painter

From the 1840s onwards, Franz Xaver Winterhalter embarked on a career trajectory that few artists achieve. He became the portraitist of choice for royalty across the continent, effectively dominating the field of official court portraiture for several decades. His client list reads like a 'who's who' of mid-19th-century European monarchy.

His connection with the British Royal Family was particularly strong and enduring. Beginning in 1842, Queen Victoria commissioned Winterhalter repeatedly. For nearly two decades, he made regular summer visits to England to paint the Queen, Prince Albert, and their growing family. He produced over 120 works for the British royals, ranging from intimate studies to grand state portraits. Victoria appreciated his speed, his discretion, and his ability to capture not only likenesses but also the dynastic image she wished to project. He became, in her words, a personal friend. His predecessor in royal favour in Britain had been Sir Thomas Lawrence, but Winterhalter brought a distinctly continental elegance.

In France, after the fall of Louis-Philippe in 1848, Winterhalter found favour again with the new regime of the Second Empire. He became the preferred painter of Emperor Napoleon III and, especially, Empress Eugénie. His portraits of the Empress, renowned for her beauty and fashion sense, are among his most iconic works, perfectly capturing the glamour and opulence associated with her court.

Beyond Britain and France, Winterhalter's services were sought by numerous other courts. He painted King Leopold I of the Belgians and his family, Queen Isabella II of Spain, Emperor Franz Joseph I and Empress Elisabeth ("Sisi") of Austria-Hungary, Tsar Alexander II of Russia and members of the Russian aristocracy, including the famously beautiful Princess Leonilla Bariatinskaya, Princess of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn. He also painted portraits for the royal families of Portugal, Prussia, and various German states. His international success was unprecedented for a portraitist in his era.

Artistic Style and Technique

Winterhalter's artistic style evolved throughout his career but consistently maintained a signature elegance and technical polish. While his early training under Stieler instilled Neoclassical principles of clarity and balanced composition, his exposure to Parisian art trends and travels, particularly to Italy in 1833-34, broadened his stylistic vocabulary. He absorbed elements of the Rococo revival, evident in the fluid lines, lighter palettes, and decorative sensibility of his mature work.

His technical mastery was undeniable, particularly in rendering textures. Winterhalter possessed an extraordinary ability to depict the specific qualities of luxurious materials – the sheen of silk and satin, the intricate delicacy of lace, the soft richness of velvet, the sparkle of diamonds and pearls, the plushness of ermine trim. This meticulous attention to costume and accessories was a hallmark of his style and greatly contributed to the appeal of his portraits, reflecting the status and wealth of his sitters.

While often flattering, his portraits were generally considered good likenesses. He skillfully balanced the need for realistic representation with the desire for idealization appropriate to high-status portraiture. He excelled at capturing graceful poses and composed expressions, conveying an air of aristocratic poise and refinement. His female portraits, in particular, were celebrated for their charm and beauty.

Winterhalter's handling of paint was typically smooth and highly finished, leaving little trace of brushwork, especially in the faces and flesh tones. His compositions ranged from relatively simple bust-length formats to complex group portraits and full-length state images set against elaborate backgrounds. His use of light was often soft and diffused, enhancing the sense of elegance and minimizing harshness.

Comparisons were inevitably made with earlier masters of court portraiture. His skill in depicting rich attire and conveying an air of effortless grace often drew parallels with the work of Sir Anthony van Dyck. While admired for his technical prowess and compositional skills, some critics felt his work lacked the psychological depth or dramatic power found in portraits by artists like Rembrandt or the grand historical narratives of Peter Paul Rubens or Paolo Veronese. Nonetheless, his specific blend of realism, idealization, and decorative flair perfectly suited the tastes of his elite clientele.

Key Masterpieces

Among Winterhalter's vast output, several works stand out as particularly representative of his style and significant in his career.

Empress Eugénie Surrounded by her Ladies in Waiting (1855), now housed in the Château de Compiègne, is perhaps his most famous group portrait. Depicting the French Empress in a pastoral setting, elegantly attired and accompanied by her attendants, the painting is a symphony of pastel colours, flowing gowns, and feminine grace. It epitomizes the romanticized glamour of the Second Empire and showcases Winterhalter's skill in complex compositions and delicate rendering of fabrics and nature.

The Royal Family (1846), part of the British Royal Collection, presents Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their five eldest children. While fulfilling its role as a dynastic image, the portrait also conveys a sense of familial warmth and intimacy, reflecting the bourgeois values Victoria and Albert sought to project. Winterhalter masterfully balances formality with a degree of informality, capturing individual likenesses within a harmonious composition.

Florinda (1852), now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (though another version exists in Boston), demonstrates a different facet of Winterhalter's work. Based on a legend associated with the fall of the Visigothic kingdom in Spain, it depicts a group of semi-nude women preparing to bathe, spied upon by King Roderic. This work allowed Winterhalter to explore the female form and indulge in a more sensual, narrative subject, moving away from strict portraiture while retaining his characteristic smooth finish and elegant figures.

Portrait of Princess Leonilla Bariatinskaya, Princess of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn (1843), housed at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, is widely considered one of his most stunning female portraits. The Princess reclines languidly on a low ottoman against a backdrop of rich crimson drapery. Her pose is daringly informal for the time, and Winterhalter captures her beauty, intelligence, and luxurious surroundings with breathtaking skill. The painting is a masterpiece of texture, colour, and composition.

Portrait of Queen Victoria (1859), another key work in the Royal Collection, shows the Queen in full Garter robes. It is a powerful state portrait, conveying majesty and authority, yet Winterhalter still manages to imbue the image with a sense of the Queen's personality. The rendering of the velvet, ermine, and jewels is exceptionally fine. These examples highlight the range and consistent quality of Winterhalter's output at the height of his career.

Collaboration and Studio Practice

The sheer volume of commissions Winterhalter received, particularly during his peak years, necessitated an efficient working method and, at times, assistance. Like many successful artists before him, including masters such as Rubens, Winterhalter maintained a studio and employed assistants. Most notable among these was his younger brother, Hermann Winterhalter (1808-1891).

Hermann was a competent painter in his own right, having followed a similar artistic path to Franz. He often collaborated with his more famous brother, particularly in producing replicas or variants of popular portraits, which were frequently requested by sitters for distribution among family members or other courts. Hermann might also have assisted with painting backgrounds or drapery in larger compositions, freeing Franz to concentrate on the faces and more critical elements.

This collaboration was a practical necessity given the demands on Franz's time. While it occasionally led to questions about the precise extent of the master's hand in every work attributed to him, it was a common practice for highly sought-after artists managing large workshops. The primary creative vision and the execution of the most important parts remained firmly under Franz Xaver Winterhalter's control. Their close relationship allowed Franz to maintain an astonishing level of output without significantly compromising the quality associated with his name.

Contemporary Context and Reception

Franz Xaver Winterhalter operated within a complex and dynamic 19th-century art world. His career coincided with the rise of Romanticism, the persistence of Neoclassicism, the emergence of Realism, and, towards the end of his life, the beginnings of Impressionism. While he associated with fellow artists, including a documented friendship with the Belgian painter Wilhelm Peter Metzler, whom he painted and visited, his primary sphere was the rarefied world of European courts.

His success was immense, particularly among his elite clientele. He commanded high fees and enjoyed unparalleled access to the highest levels of society. His portraits were widely admired for their elegance, technical brilliance, and flattering likenesses. They perfectly captured the self-image of the ruling classes in an age before photography fully usurped the role of painted portraiture for official purposes.

However, Winterhalter was not without his critics. From early in his Paris career, some commentators found his work superficial, overly concerned with outward appearances, and lacking in psychological depth or artistic innovation. He was sometimes dismissed as a mere "painter of fashion," skilled at rendering silks and jewels but offering little substance beneath the glittering surface. His style could seem formulaic compared to the more challenging or emotionally charged works of Romantic painters like Delacroix or the stark realism pursued by others like Gustave Courbet. French society portraitists like Édouard Dubufe worked in a similar, popular vein.

Despite these criticisms, Winterhalter's popularity with patrons remained unwavering. His success at the Paris Salon, the premier art exhibition venue, confirmed his standing, even if critical opinions were divided. He skillfully navigated the demands of his patrons, providing them with images that conveyed status, beauty, and decorum. His international renown far surpassed that of many artists considered more 'serious' by contemporary critics. He essentially created his own niche, becoming the undisputed master of the international court portrait in his time.

Later Years and Legacy

Winterhalter remained highly active and in demand throughout the 1850s and 1860s. He continued to travel between European capitals, fulfilling commissions. He maintained his studio in Paris but also spent time in Germany, acquiring a villa in Baden-Baden, a fashionable spa town, where he could rest and recuperate. His simple personal lifestyle contrasted with the opulence depicted in his paintings.

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 marked a turning point. The fall of the Second French Empire deprived him of his most important patrons, Napoleon III and Eugénie. Although he had worked extensively for other courts, the upheaval in France significantly impacted his base of operations. He did not return to live in Paris after the war.

His health began to decline in his later years. While visiting Frankfurt am Main in the summer of 1873, he contracted typhus and died there on July 8th, at the age of 68.

Following his death, Winterhalter's reputation entered a period of decline. The rise of Impressionism and subsequent modernist movements shifted artistic tastes away from the polished academic style he represented. His work came to be seen by many as old-fashioned, associated with a bygone era of aristocratic privilege and perceived superficiality. For much of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, he was largely overlooked by art historians focused on the avant-garde.

However, the late 20th century saw a significant reassessment of Winterhalter's work. Exhibitions and scholarly research brought renewed attention to his technical mastery, his stylistic elegance, and his unique historical significance. He is now recognized not only as a supremely skilled portraitist but also as an invaluable visual chronicler of a specific social milieu and historical period. His paintings offer unparalleled insight into the personalities, fashions, and self-representation of mid-19th-century European royalty. While perhaps not an innovator on the scale of some contemporaries, his contribution to the tradition of grand portraiture, following figures like Van Dyck and Lawrence and preceding later society painters like James Tissot or John Singer Sargent, is now widely acknowledged.

Conclusion

Franz Xaver Winterhalter carved a unique and remarkably successful path in 19th-century European art. Rising from humble beginnings, he became the most sought-after court portraitist of his generation, creating a vast and glittering gallery of emperors, queens, princes, and aristocrats. His distinctive style, blending Neoclassical structure with Rococo grace and Romantic sensibility, perfectly captured the elegance and opulence his sitters wished to project.

While sometimes criticized for a perceived lack of depth or an overemphasis on surface glamour, his technical brilliance, particularly in rendering fabrics and achieving flattering likenesses, was undeniable. His work provides an irreplaceable visual record of the ruling elites of Europe during the final decades before the age of photography fundamentally changed the nature of portraiture. Today, Winterhalter's paintings are appreciated not only for their aesthetic appeal and technical virtuosity but also as vital historical documents, offering a window onto the vanished world of 19th-century court life. He remains a pivotal figure in the history of portrait painting.