Fritz (Friedrich) Rojka, an Austrian artist born in the vibrant cultural heart of Vienna in 1878, dedicated his life to the meticulous observation and depiction of the world around him. Active during a period of immense artistic transformation, Rojka carved out a niche for himself, primarily focusing on still life and portraiture. His career spanned the final decades of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the tumultuous years of the First Austrian Republic, concluding with his passing in 1939, a year that marked the beginning of another global conflict. While perhaps not as internationally renowned as some of his Viennese contemporaries like Gustav Klimt or Egon Schiele, Rojka’s work offers a valuable glimpse into the enduring traditions and subtle shifts within Austrian art during the early 20th century.

The Viennese Milieu: A Crucible of Art

To understand Fritz Rojka, one must first appreciate the artistic environment of Vienna at the turn of the 20th century. The city was a dynamic hub of intellectual and artistic activity, a place where tradition and modernity clashed and coalesced. The Vienna Secession, founded in 1897 by artists such as Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, and Josef Hoffmann, had already challenged the conservative artistic establishment, paving the way for new forms of expression. Figures like Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka would soon push the boundaries of Expressionism, capturing the psychological intensity of the era.

While these avant-garde movements were making headlines, a significant number of artists continued to work in more traditional modes, refining their skills in established genres like landscape, portraiture, and still life. It is within this broader context that Rojka’s artistic practice likely developed. He would have been aware of the radical innovations happening around him, but his own work suggests a preference for a more introspective and representational approach, focusing on the tangible beauty of everyday objects and the character of individuals.

Artistic Development and Focus

Information regarding Fritz Rojka's formal artistic training or specific mentors is not extensively documented in readily available sources. However, it is reasonable to assume he received academic training, as was common for artists of his time who aimed for proficiency in representational art. Vienna boasted prestigious institutions like the Academy of Fine Arts, which had nurtured generations of Austrian painters. His dedication to genres like still life and portraiture suggests a grounding in classical techniques, emphasizing careful drawing, composition, and the nuanced use of color and light.

Rojka's commitment to these genres speaks to an appreciation for the enduring qualities of art that captures the quiet dignity of the everyday. Still life, in particular, allows for controlled study of form, texture, and light, offering a space for contemplation away from the grand narratives or societal critiques that preoccupied some of his contemporaries. His portraits, including a self-portrait from 1925, would have involved a close study of human physiognomy and an attempt to convey personality or mood.

The Art of Still Life: Rojka's Enduring Theme

Fritz Rojka’s oeuvre demonstrates a particular affinity for still life painting. This genre, with its rich history stretching back to the Dutch Golden Age masters like Willem Kalf and Pieter Claesz, offered artists a unique platform for showcasing technical skill and exploring the symbolic potential of everyday objects. Rojka’s still lifes were diverse in their subject matter, reflecting an eye for the beauty and interest in the commonplace.

His subjects reportedly included an array of items, painting a picture of a keen observer of his domestic and natural surroundings. These included "small flowers, wild ducks, snow-covered wooden floors, kitchens, flowers, butterflies, birds, fruits, azaleas, kettles, whistles, historical determinists, antique cacti, peaches in a red glass bowl, irises, parrots, and grapes." This eclectic list suggests a fascination with both the organic and the man-made, the ephemeral beauty of a bloom and the solid presence of a household utensil.

One particularly evocative description mentions a still life featuring "a historical determinist's kettle, a bowl of fruit, and a newspaper." This title hints at a potential layer of intellectual or symbolic meaning beyond the mere depiction of objects, perhaps a subtle commentary or a personal reflection embedded within the composition. The inclusion of a newspaper, a contemporary item, grounds the work in its time, while the "historical determinist's kettle" adds an intriguing, somewhat enigmatic element.

The dimensions of some of his still life works are recorded, such as one piece measuring 20 x 15.8 cm. Such relatively small dimensions suggest works intended for intimate viewing, perhaps for private homes rather than large public galleries, aligning with the personal and contemplative nature of the still life genre.

Portraiture and Other Works

Beyond still lifes, Fritz Rojka also engaged in portraiture. A self-portrait dated 1925 is a significant work, offering a direct insight into how the artist saw himself or wished to be perceived at that point in his career. Portraiture demands not only technical skill in capturing a likeness but also an ability to convey something of the sitter's inner life or social standing. Another recorded portrait by Rojka measures 18 x 26 cm, again suggesting a scale suited for personal appreciation.

One of his works mentioned in auction records is titled Magd mit rotem Kopftuch (Maid with a Red Headscarf). This piece, likely a portrait or genre scene, focuses on a common figure, suggesting an interest in depicting ordinary people, a theme that runs parallel to his still lifes of everyday objects. The "red headscarf" provides a focal point of color and character.

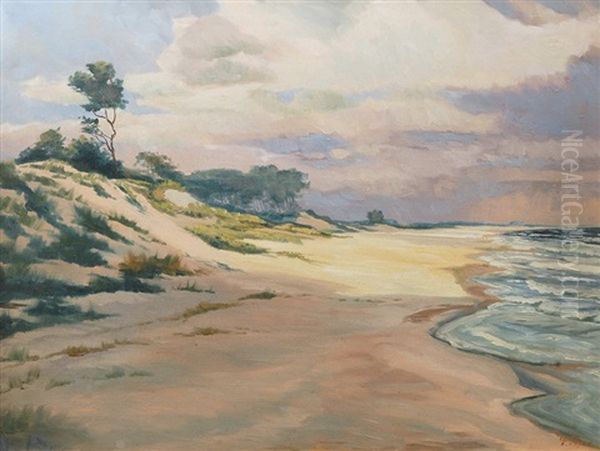

Another notable piece is Beach on the Baltic Sea. This title indicates that Rojka also ventured into landscape or seascape painting, broadening his thematic range. The Baltic Sea, with its distinctive light and coastal features, would have offered a different set of artistic challenges and opportunities compared to indoor still lifes or portraits. This work was recorded as having been sold at auction for 600 Euros, indicating a continued, if modest, market presence for his art in more recent times.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Fritz Rojka’s work was not confined to his studio; he participated in the public art scene of his time. A significant event in his career was his inclusion in the Große Kunstausstellung (Great Art Exhibition) of 1927. This exhibition was held at the prestigious Künstlerhaus, located at Karlsplatz 5 in Vienna. The Künstlerhaus was a major venue for established artists in Vienna, and participation in its exhibitions signified a degree of recognition within the Austrian art community.

The 1927 exhibition catalogue would have listed Rojka alongside numerous other Austrian artists, some of whom might have included figures like Rudolf Böhm or Karl Praxelis, who were also active during this period. Being part of such a large-scale exhibition provided artists with visibility, opportunities for sales, and critical review.

Furthermore, it is mentioned that Rojka's still life works were included in a publication series or collection titled "Austria - Great Masters." While the exact nature of this publication requires further research, its title suggests an effort to canonize and promote significant Austrian artists, and Rojka's inclusion would have been a mark of esteem.

The continued appearance of his works in auction catalogues, such as those from Auktionshaus Stahl (with a mention of an auction on October 2, 2023, though specific details of that event related to Rojka are scarce in the provided summary) and other online auctions (like one noted for September 17, 2024), demonstrates that his paintings retain value and interest among collectors. This posthumous market activity is a testament to the enduring appeal of his skillful and considered art.

Artistic Style and Potential Influences

Based on the descriptions of his work, Fritz Rojka’s artistic style appears to be rooted in realism, characterized by "detailed observation of nature and life" and a "unique artistic skill." This suggests a commitment to representational accuracy and a high level of craftsmanship. His still lifes, with their focus on texture, light, and the specific character of objects, would have demanded a patient and meticulous approach.

While direct evidence of his influences is not explicitly stated, one can speculate on the artistic currents that might have shaped his vision. The long tradition of European still life painting, particularly the aforementioned 17th-century Dutch and Flemish masters, often served as a foundational influence for artists working in this genre. Their mastery of illusionism, complex compositions, and symbolic content set a high bar.

In the context of early 20th-century Vienna, even artists working in a more traditional vein would have been aware of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. The Impressionists' focus on light and everyday scenes, and the Post-Impressionists' (like Paul Cézanne, whose structural approach to still life was revolutionary) exploration of form and color, had a profound impact on European art. While Rojka may not have adopted their techniques wholesale, the general artistic climate was one of increased attention to the subjective experience of seeing and the formal qualities of painting.

The Biedermeier period in Austrian art (roughly 1815-1848), with its emphasis on domesticity, realism, and detailed depictions of everyday life, might also be considered a distant cultural ancestor to Rojka's focus. Artists like Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, known for his portraits, genre scenes, and incredibly detailed still lifes, exemplified this earlier Austrian tradition of meticulous realism.

It is also possible that Rojka was influenced by contemporary realist painters in Austria and Germany who chose not to follow the more radical paths of Expressionism or abstraction but continued to find value in representational art. The artistic landscape was diverse, and not every artist felt compelled to join the avant-garde.

Contemporaries in the Viennese Art World

Fritz Rojka practiced his art during a period populated by a constellation of remarkable talents in Vienna and the broader Austrian sphere. Understanding his position requires acknowledging some of these other figures, who created a rich and varied artistic tapestry.

The towering figures of the Vienna Secession, Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) and Koloman Moser (1868-1918), were his older contemporaries. Their ornate symbolism and embrace of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) defined an era. Following them, the raw, psychological intensity of Egon Schiele (1890-1918) and Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980) represented the vanguard of Austrian Expressionism. Richard Gerstl (1883-1908), another brilliant Expressionist, had a tragically short career but produced powerful, psychologically charged portraits.

Beyond these well-known names, many other artists contributed to the Viennese scene. Alfred Kubin (1877-1959), a contemporary of Rojka, was known for his dark, symbolic, and often fantastical drawings and illustrations. Artists like Carl Moll (1861-1945), a co-founder of the Secession and later a proponent of a more atmospheric, Impressionist-influenced style, also played significant roles. The aforementioned Rudolf Böhm and Karl Praxelis, who likely exhibited alongside Rojka, represented the cohort of artists active in the established exhibition societies.

Even if Rojka’s style differed significantly from these artists, their collective presence created the artistic environment in which he worked. The debates, exhibitions, and varying artistic philosophies would have formed the backdrop to his own creative endeavors. His choice to focus on more traditional genres can be seen as a deliberate path taken within this complex and dynamic art world.

Legacy and Historical Placement

Fritz Rojka's legacy is that of a dedicated and skilled painter who contributed to the Austrian artistic tradition through his intimate and carefully observed still lifes and portraits. He may not have been an avant-garde revolutionary, but his work possesses a quiet integrity and a commitment to the craft of painting. Artists like Rojka are essential to a complete understanding of an artistic era, as they represent the continuity of established genres and skills even amidst radical change.

His inclusion in the 1927 Große Kunstausstellung and the "Austria - Great Masters" publication suggests he achieved a notable level of recognition during his lifetime. The continued, albeit perhaps specialized, interest in his work on the art market indicates that his paintings are still valued for their aesthetic qualities and historical context.

In the grand narrative of art history, which often prioritizes groundbreaking innovation, artists like Fritz Rojka can sometimes be overlooked. However, his dedication to capturing the beauty and character of his immediate world provides a valuable counterpoint to the more dramatic artistic statements of his time. His paintings offer a window into a sensibility that found profound meaning in the careful depiction of the everyday, a tradition that has an enduring appeal.

He represents a strand of early 20th-century art that, while not overtly modernist in the disruptive sense, was nonetheless a product of its time, reflecting a meticulous engagement with the visual world. His life (1878-1939) places him squarely within a period of profound social, political, and artistic upheaval, yet his work seems to seek a measure of stability and timelessness through the focused study of his subjects.

Conclusion: A Quiet Observer

Fritz Rojka stands as a testament to the enduring power of representational art and the quiet dedication of an artist committed to his craft. Born and active in Vienna, a city at the forefront of artistic innovation, Rojka chose a path that emphasized meticulous observation and the subtle beauties of still life and portraiture. His works, such as Magd mit rotem Kopftuch and Beach on the Baltic Sea, alongside his numerous still lifes featuring subjects from flowers to household items, reveal an artist deeply engaged with the visual richness of his surroundings.

While he may not have achieved the same level of fame as some of his more radical Viennese contemporaries like Klimt, Schiele, or Kokoschka, Rojka’s contributions are nonetheless significant. He participated in important exhibitions like the Große Kunstausstellung of 1927 and earned a place in collections recognizing Austrian masters. His art continues to find appreciation, reminding us of the diverse artistic expressions that flourished in the early 20th century. Fritz Rojka’s legacy is that of a skilled Viennese painter, a quiet observer who found enduring value in the careful and considered depiction of the world around him.