Gabriel Loppé (1825-1913) stands as a unique and compelling figure in the annals of 19th-century art. A Frenchman by birth, he became inextricably linked with the majestic and formidable landscapes of the Alps, dedicating much of his life to capturing their essence not only as a painter but also as a pioneering mountaineer and an accomplished photographer. His work offers a fascinating intersection of artistic endeavor, adventurous spirit, and a keen observation of both the natural world and the burgeoning technological advancements of his era. Loppé was more than a mere landscape artist; he was an interpreter of the sublime, a man who sought to convey the raw power and ethereal beauty of high-altitude environments from a perspective few had dared to attain.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in Montpellier, France, in 1825, Gabriel Loppé's lineage was a blend of Norman Catholic heritage from his father and Southern French roots from his Toulouse-born mother. From a young age, he exhibited a natural aptitude for the arts. However, his formal artistic education in Paris was cut short. At the tender age of 16, concerns for his health prompted his family to relocate, and they settled in Switzerland. This move proved to be a pivotal moment in Loppé's life, immersing him in the very landscapes that would become his lifelong muse.

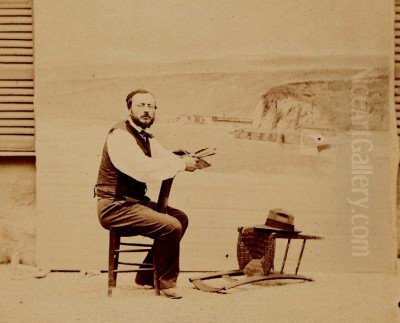

In Bern, Loppé continued his artistic development, notably studying in an outdoor studio. This early exposure to plein air painting, or painting directly from nature, would become a hallmark of his practice. Unlike many of his contemporaries who relied on sketches made outdoors to be later developed into finished pieces in the studio, Loppé often worked extensively on his canvases amidst the challenging conditions of the mountains. He was largely a self-taught artist, his skills honed through direct observation and an unwavering dedication to his craft. This independent spirit allowed him to develop a style that was both personal and deeply responsive to the unique demands of his chosen subject matter.

The Mountaineer-Painter: A Dual Passion

Loppé's arrival in the Alps ignited a passion that would define his career: mountaineering. He was not content to view the mountains from afar; he felt compelled to explore their highest reaches, to stand upon their summits, and to experience their grandeur firsthand. This adventurous spirit was not separate from his artistic pursuits but rather intrinsically linked to them. He became one of the first, if not the very first, artist to paint en plein air at significant altitudes, a feat that required immense physical stamina, technical ingenuity, and an unyielding commitment.

His expeditions often saw him carrying not only climbing gear but also his easel, canvases, and paints to dizzying heights. He is known to have climbed Mont Blanc, the highest peak in the Alps, numerous times – some accounts suggest over forty ascents. Each climb was an opportunity to observe and record the subtle nuances of light, atmosphere, and form that characterized these elevated realms. He sought to capture the fleeting moments of alpine dawns and sunsets, the crystalline clarity of the air, the formidable architecture of glaciers, and the sheer scale of the peaks.

This dedication to authenticity set him apart. While artists like J.M.W. Turner had earlier conveyed the sublime power of the Alps with dramatic romanticism, often from lower vantage points or based on sketches, Loppé’s work was grounded in direct, prolonged immersion in the high-altitude environment. His paintings possess an immediacy and a palpable sense of atmosphere that could only come from such intimate experience.

Loppé’s passion for the mountains also led him to become deeply integrated into the burgeoning mountaineering community. He forged strong friendships with many British climbers, who were at the forefront of Alpine exploration during this period. His expertise and artistic talent were highly regarded, and in 1864, he became the first French member of the prestigious Alpine Club in London. His paintings often served as valuable visual records for these climbers, offering geographically accurate depictions of routes and features.

One notable anecdote from his mountaineering life occurred in 1867 when he attempted an ascent of Mont Blanc. While he was a seasoned climber, on this occasion, he was outpaced by the American female mountaineer Isabella Straton, a testament to the growing diversity and skill within the climbing community. Such experiences, however, did not deter his love for the region. He discovered Chamonix in 1849 and it became a central hub for his activities for over six decades.

Capturing the Ephemeral: Loppé's Artistic Style

Gabriel Loppé’s artistic style is characterized by a compelling fusion of meticulous realism and a profound romantic sensibility. He possessed a remarkable ability to render the geological intricacies of rock formations, the subtle textures of snow and ice, and the dramatic play of light and shadow across vast mountain panoramas. His works are not merely topographical records; they are imbued with a sense of awe and wonder, conveying the emotional impact of these sublime landscapes.

His commitment to painting at high altitudes lent his work a unique vibrancy and spontaneity. He was particularly adept at capturing the transient effects of weather and light – the alpenglow on a summit at dusk, the mist swirling through a valley, or the stark, cold light of a winter's day. His palette often employed cool blues, greys, and whites to convey the icy atmosphere, punctuated by the warmer tones of sunrise or sunset, or the deep greens of lower alpine meadows.

Loppé often worked on large-scale canvases, creating panoramic views that sought to envelop the viewer in the grandeur of the Alpine world. These works demonstrate his skill in composition, balancing vast expanses with intricate detail. He paid close attention to the specific conditions of the Alpine environment, depicting crevasses, seracs, and glacial flows with an accuracy born of firsthand knowledge. This scientific observation did not detract from the artistic merit but rather enhanced it, lending his paintings a profound sense of authenticity.

His style can be seen in relation to other landscape traditions of the 19th century. While he shared the Barbizon School's dedication to outdoor painting, exemplified by artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Théodore Rousseau, Loppé took this practice to unprecedented extremes. His work also resonates with the detailed naturalism found in some aspects of the Pre-Raphaelite landscapes in Britain, though his primary focus remained the raw, untamed nature of the high Alps rather than the more pastoral scenes often favored by them. One might also see parallels with the atmospheric concerns of early Impressionists like Claude Monet or Alfred Sisley, particularly in Loppé's sensitivity to light, though his detailed rendering often set him apart from their looser brushwork.

The Swiss painter Alexandre Calame, a near contemporary, was also renowned for his Alpine scenes, often imbued with a dramatic, romantic spirit. Loppé would have been aware of Calame's work, as well as that of François Diday, another prominent Swiss Alpine painter. While sharing a common subject, Loppé's approach was distinguished by his active mountaineering and his commitment to painting at extreme altitudes, giving his work a unique experiential quality. Other Swiss artists like Jean-Antoine Linck and Pierre-Louis de Riuville also contributed to the rich tradition of Alpine landscape painting in the region.

Key Works: Windows into the Alpine Soul

Several of Gabriel Loppé's paintings stand out as iconic representations of his artistic vision and his deep connection with the Alps.

Mont Blanc: Sunset is perhaps one of his most celebrated achievements. Painted in 1873, reportedly during an ascent with the British writer and mountaineer Sir Leslie Stephen (who, it should be noted, was a literary figure and not a visual artist himself, though a keen observer of art and nature), this work captures the breathtaking spectacle of the sun setting as viewed from the very summit of Europe's highest peak. The painting likely conveys the intense, fleeting colors that bathe the snow and surrounding peaks in a warm, ethereal glow, contrasted with the deepening shadows in the valleys below. It is a testament to his daring and his ability to work under extreme conditions to capture a truly unique perspective.

Mer de Glace and the Aiguille du Tacul showcases his fascination with glaciers. The Mer de Glace, or "Sea of Ice," is one of the largest glaciers in the Mont Blanc massif, and Loppé would have known its every nuance. This painting would depict the vast, undulating expanse of the glacier, its surface fractured by crevasses and seracs, with the formidable granite spire of the Aiguille du Tacul rising in the background. His detailed rendering of ice formations, capturing their translucency and varied textures, would be a prominent feature.

Gstei bei Gstaad Valley at Feusenberg demonstrates Loppé's ability to capture the specific character of different Alpine regions and seasons. This work likely portrays a winter scene in the Swiss valley, perhaps with snow-laden trees, a frozen river, and the crisp, clear light of a cold day. It would highlight his skill in depicting the subtle gradations of white and blue in a snow-covered landscape, and the peaceful yet stark beauty of the Alps in winter.

Another significant work, often mentioned, is his depiction of the Glacier des Grandes Jorasses. This painting would focus on the imposing icefall and the dramatic peaks of the Grandes Jorasses, showcasing his ability to convey both the immense scale and the intricate details of glacial formations and high mountain architecture.

His paintings were frequently exhibited in London and Paris, where they received considerable acclaim. His work was featured at the 1862 International Exhibition in London, where Sir Leslie Stephen himself praised Loppé's contributions for their accuracy and artistic merit. In 1870, Loppé further solidified his presence in the art world by opening the "Gabriel Loppé Alpine Gallery," likely in Chamonix or Geneva, to showcase his unique body of work.

A Pioneer with the Lens: Loppé the Photographer

Beyond his remarkable achievements as a painter and mountaineer, Gabriel Loppé was also an enthusiastic and skilled early photographer. In an era when photography was still a relatively new and cumbersome technology, Loppé embraced it as another means of capturing the world around him. His photographic subjects were diverse, ranging from intimate family portraits to further documentation of the natural landscapes he so loved.

His photographic work, like his painting, often focused on the Alps, providing valuable records of glacial conditions, mountain topography, and the experiences of early climbers. These photographs would have complemented his paintings, offering a different, perhaps more starkly objective, view of the scenes he also rendered in oil. The challenges of early photography, particularly in harsh mountain environments with bulky equipment and delicate chemical processes, would have been considerable, further highlighting Loppé's tenacity.

Loppé’s interest in photography also extended to the urban environment and the technological marvels of his age. He was an early observer and recorder of innovations like steam trains and the transformative power of electric lighting in cities. One of his most famous photographs, which garnered international attention and was even exhibited at the Royal Academy in London, captured the dramatic moment of the Eiffel Tower being struck by lightning. This image perfectly encapsulated his fascination with both natural phenomena and human ingenuity. His photographic endeavors place him alongside other pioneering photographers who were exploring the medium's potential, such as Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon) in France, known for his portraits and early aerial photography, or British photographers like Roger Fenton, famed for his Crimean War images and landscapes.

An Eye on Modernity: Technology and Urban Change

Loppé's engagement with photography and his depiction of technological advancements reveal an artist who was keenly aware of the changing world around him. While his heart lay in the timeless grandeur of the Alps, he did not shy away from the transformations of the 19th century. His photographs of steam trains and electric lights demonstrate an appreciation for the dynamism of modern life.

This interest in contemporary developments provides a broader context for his work. He was not an artist isolated in an ivory tower (or an ice cave, as it were) but one who observed and documented the forces shaping his society. This dual focus – on the enduring power of nature and the rapid pace of human innovation – adds another layer of complexity to his artistic persona. His documentation of these changes can be seen as part of a wider artistic and social current, where artists like Gustave Courbet, a leading figure of Realism, sought to depict contemporary life and labor, or later, Impressionists captured the fleeting moments of modern Parisian life. While Loppé's primary focus remained the Alps, his forays into these other subjects show a versatile and observant mind.

Connections and Contemporaries

Gabriel Loppé operated within a vibrant artistic and intellectual milieu. His membership in the Alpine Club connected him with leading British mountaineers and writers like Sir Leslie Stephen. In the art world, his work can be situated within the broader trends of 19th-century landscape painting.

As mentioned, Swiss artists like Alexandre Calame and François Diday were significant figures in Alpine art. Loppé's relationship with Diday was reportedly close, suggesting mutual influence. The tradition of Swiss landscape painting was rich, with earlier figures like Caspar Wolf paving the way for the romantic depiction of the Alps. Later Swiss artists like Ferdinand Hodler would also find profound inspiration in the mountains, though with a more symbolic and monumental style.

In France, the Barbizon School painters, including Corot, Rousseau, and Charles-François Daubigny, had revolutionized landscape painting by emphasizing direct observation from nature. Loppé shared this ethos, albeit in a far more extreme environment. The rise of Realism with Courbet also stressed truth to nature and contemporary subjects, a sentiment that resonates with Loppé's detailed renderings and his interest in modern technology.

The burgeoning Impressionist movement, with figures like Monet, Pissarro, and Sisley, focused on capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, often with broken brushwork. While Loppé's technique was generally more detailed, his sensitivity to atmospheric conditions and his plein air practice show some common ground.

In Britain, the influence of J.M.W. Turner on the depiction of sublime landscapes, including the Alps, was immense. The writer and art critic John Ruskin, a passionate advocate for Turner and a lover of the Alps himself, championed detailed observation of nature, a principle Loppé clearly embodied. Another British figure relevant to the Alpine context is Edward Whymper, the famed conqueror of the Matterhorn, who was also a skilled illustrator, documenting his climbs with dramatic engravings. Loppé’s work provided a painted counterpart to such illustrative records.

Loppé's deep connections within the Chamonix community, particularly with families like the Tairraz (known for their dynasty of mountain guides and photographers) and the photographer François Couttet, further enriched his life and work. He became an ambassador for the Salvan Valley, encouraging exploration through his connections at the Alpine Club.

Final Years and Enduring Legacy

Gabriel Loppé continued to paint and explore the Alps throughout his long life. He remained deeply connected to Chamonix and also spent time in Geneva, where he had his gallery. His dedication to his dual passions of art and mountaineering never waned. He passed away in Paris in 1913, at the age of 88, leaving behind an extensive and unique body of work.

His legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he pushed the boundaries of plein air practice, demonstrating that it was possible to create significant artworks under the most challenging environmental conditions. His paintings offer an unparalleled visual record of the 19th-century Alpine landscape, rendered with both scientific accuracy and profound artistic sensibility. They remain highly sought after and are found in museums and private collections, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris and various Alpine museums in Switzerland.

As a mountaineer, he was a pioneer, part of the golden age of Alpinism, contributing to the exploration and popularization of the high peaks. His role as the first French member of the Alpine Club underscores his standing in this community.

As a photographer, he embraced a new technology, using it to complement his artistic vision and to document the world around him, from the majestic Alps to the symbols of modernity. His photograph of the Eiffel Tower struck by lightning remains an iconic image.

Gabriel Loppé's life and work continue to inspire. Artists and mountaineers alike can draw inspiration from his adventurous spirit, his dedication to his craft, and his profound love for the mountains. In 2022, for instance, British mountaineer and artist James Hart Dyke recreated Loppé's feat of painting the Mont Blanc sunset from the summit, a tribute to Loppé's pioneering endeavor nearly 150 years earlier.

Gabriel Loppé was more than just an artist who painted mountains; he was an artist whose very soul was forged in the alpine crucible. His work remains a powerful testament to the sublime beauty of the natural world and the indomitable human spirit that seeks to understand and express it. He carved a unique niche in art history, a painter of the peaks, whose canvases transport us to the breathtaking, rarefied air of the high Alps.