Introduction: Bridging Naples and London

Gabriele Carelli stands as a significant figure in nineteenth-century landscape painting, particularly admired for his mastery of the watercolour medium. Born in Naples in 1820 and passing away in Menton, France, in 1900, Carelli's life and career traversed the vibrant artistic milieu of his native Italy and the established art world of Victorian England. He specialised in topographical views, capturing the landscapes and architecture of Europe and the Middle East with a freshness and clarity that earned him considerable acclaim, including royal patronage. His work forms a fascinating link between the Neapolitan Scuola di Posillipo (Posillipo School) and the rich tradition of British watercolour painting.

Neapolitan Roots: The Legacy of the Posillipo School

Gabriele Carelli was born into an artistic dynasty. His father, Raffaele Carelli (1795-1864), was a prominent landscape painter and a key member of the Posillipo School. This movement, flourishing in Naples during the first half of the nineteenth century, marked a departure from the strictures of Neoclassical formalism that dominated academic art. Its proponents favoured a more direct, naturalistic approach to landscape, often working en plein air (outdoors) to capture the specific light and atmosphere of the Bay of Naples and its surroundings.

The school's origins are often traced to the Dutch painter Anton Sminck Pitloo (1790-1837), who settled in Naples and encouraged his students to paint directly from nature. Alongside Raffaele Carelli, other leading figures included Giacinto Gigante (1806-1876), whose atmospheric watercolours and oils profoundly shaped the school's direction. Gabriele, along with his brother Consalvo Carelli (1818-1900), grew up immersed in this environment, learning the techniques of drawing and watercolour from their father and absorbing the school's emphasis on capturing the picturesque beauty of their native region.

The Posillipo painters often favoured watercolour and gouache for their portability and immediacy, ideal for sketching trips along the coast or into the Campanian countryside. Their subjects included coastal views, ancient ruins like Pompeii and Paestum, and scenes of local life, rendered with a sensitivity to light and colour that was relatively novel for Italian landscape painting at the time. This training provided Gabriele Carelli with a superb technical foundation and an eye for picturesque detail that would serve him throughout his career. His early works inevitably reflect this Neapolitan heritage.

Discovery and the Move to England

A pivotal moment in Carelli's career occurred in 1847. While visiting Naples, William Cavendish, the 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858), a renowned art collector and patron, encountered the young artist's work. Impressed by Carelli's talent, the Duke became his patron, a connection that likely facilitated Carelli's decision to relocate. He eventually settled in England, establishing himself within the British art scene, although he maintained connections with Italy and continued to travel extensively.

This move marked a significant shift. While London offered a larger, more established art market and access to influential patrons and institutions, it also meant adapting to a different artistic culture. Britain had its own powerful tradition of landscape painting, dominated in the preceding generation by giants like J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and John Constable (1776-1837). Watercolour painting, in particular, held a prestigious position, supported by dedicated societies and a large collector base.

Carelli's Neapolitan training, with its emphasis on clear light and precise rendering of topography, found resonance within certain strands of the British watercolour tradition. Artists like David Roberts (1796-1864), known for his detailed views of Britain, Europe, and the Near East, shared a similar focus on architectural accuracy and scenic effect. Carelli's ability to produce highly finished, evocative watercolours appealed to the Victorian taste for both the picturesque and the geographically specific.

A Career in Victorian Britain

Settling in England, Carelli built a successful career primarily as a watercolourist. He became a regular exhibitor at London's prestigious art venues. His skill was formally recognised when he was elected an Associate of the Royal Watercolour Society (often known as the Old Water-Colour Society) in 1866, achieving full membership in 1874. Membership in the RWS was a mark of distinction, placing him alongside leading British practitioners of the medium, such as Myles Birket Foster (1825-1899) and Alfred William Hunt (1830-1896).

His works often depicted scenes from his travels, bringing views of Italy, the Mediterranean, and further afield to a British audience. The Victorian era was a period of expanding tourism and colonial reach, fostering a keen public interest in foreign lands. Carelli's watercolours, detailed and accessible, catered to this fascination, offering windows onto sunnier climes and historic sites. He painted popular Italian destinations like Venice, Rome, and the Amalfi Coast, subjects familiar to British travellers undertaking the Grand Tour or its later iterations.

His style, while rooted in the Posillipo tradition, likely adapted subtly to British tastes. It retained the clarity and bright palette associated with his Neapolitan origins but perhaps gained a degree of finish and detail favoured by the Victorian market. He worked alongside other foreign artists who found success in London, such as the German-born Carl Haag (1820-1915), who also specialised in watercolours, particularly scenes from the Middle East, and enjoyed royal favour.

Royal Recognition: Patronage from Queen Victoria

Carelli's success extended to the highest echelons of British society. From the 1880s onwards, he gained the favour of Queen Victoria. The Queen herself was an amateur watercolourist and an avid collector, particularly of views commemorating her travels and interests. She commissioned works from numerous artists, documenting landscapes, events, and residences across Britain and the Empire. Her patronage provided Carelli with significant prestige and likely led to further commissions from aristocratic circles.

The Royal Collection Trust holds works by Carelli, testament to this connection. This patronage aligns with Victoria's known appreciation for artists who could render scenes with accuracy and charm. Other artists who benefited from her interest in landscape and topographical views included William Leighton Leitch (1804-1883), who was also her watercolour tutor for many years. Carelli's ability to capture the essence of a place, whether a familiar British castle or an exotic foreign locale, clearly appealed to the monarch.

Extensive Travels: Broadening Horizons

Travel was fundamental to Carelli's art. While Italy remained a constant source of inspiration, his journeys took him much further afield. He visited and painted scenes across Europe, but significantly, he also travelled to North Africa and the Middle East, including Egypt and Palestine. These expeditions provided him with fresh subject matter that tapped into the burgeoning European fascination with 'the Orient'.

His Middle Eastern views place him within the context of Orientalist painting, a genre popular throughout the nineteenth century. Artists like the aforementioned David Roberts, the Frenchman Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), and John Frederick Lewis (1804-1876), who lived for years in Cairo, created images of the region that blended topographical observation with romanticised visions of exotic cultures and ancient ruins. Carelli's contributions to this genre likely focused on the landscape and architectural wonders, rendered in his characteristic clear watercolour style.

Views of Egyptian temples, bustling Cairo streets, or Holy Land sites would have found a ready market in Britain. These works allowed viewers to vicariously experience lands that were becoming increasingly accessible yet still seemed remote and mysterious. Carelli's travels provided a continuous stream of subjects, ensuring his work remained varied and appealing throughout his long career. He captured the distinct light and atmosphere of these diverse locations, from the cool dampness of a Scottish landscape to the brilliant sunshine of the Nile Valley.

Artistic Style: Clarity and Light in Watercolour

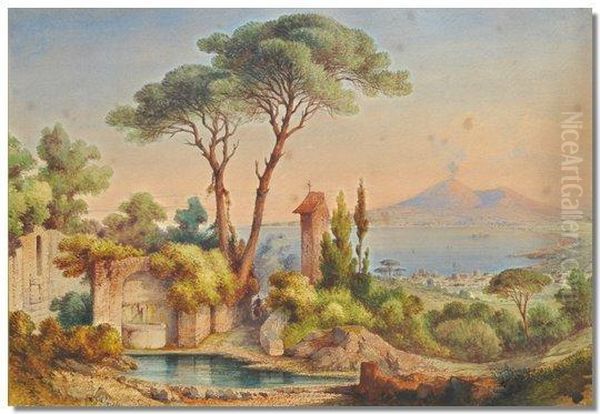

Gabriele Carelli's reputation rests firmly on his skill as a watercolourist. His style is characterised by its clarity, precision, and sensitivity to light and atmosphere. Drawing upon his Posillipo School training, he excelled at topographical accuracy, carefully delineating architecture and landscape features. His works are often detailed but rarely feel laboured; they retain a sense of freshness and immediacy.

He typically employed transparent watercolour washes, building up layers of colour to achieve luminosity and depth. His palette was often bright and clean, reflecting the strong Mediterranean light of his native Naples or the exotic locales he visited. Even when depicting more northern scenes, his work often possesses a certain radiance. He had a fine sense of composition, arranging elements to create balanced and picturesque views.

Compared to the dramatic atmospheric effects of J.M.W. Turner or the looser, more texturally focused work of contemporary British watercolourists like David Cox (1783-1859) or Peter De Wint (1784-1849), Carelli's style appears more controlled and descriptive. It aligns more closely with the tradition of topographical view painting, prioritising accurate representation while still conveying the beauty and mood of the scene. His work can be seen as a continuation and refinement of the Neapolitan veduta tradition, adapted for an international audience.

His technical proficiency was considerable. He handled complex architectural subjects with ease, capturing intricate details without sacrificing the overall harmony of the composition. Figures are often included to add scale and life to his scenes, but the landscape or cityscape remains the primary focus. His watercolours provided patrons with elegant and enduring records of places they had visited or dreamed of seeing.

Representative Works: A Visual Journey

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be lacking, numerous works by Gabriele Carelli survive in public and private collections, illustrating the range of his subjects. His Italian views are perhaps most numerous, including many depictions of Venice – the Doge's Palace, the Grand Canal, Santa Maria della Salute – rendered with his typical clarity and attention to the interplay of light, water, and architecture. Views of Rome, Florence, Naples, and the Amalfi Coast also feature prominently.

His travels are documented in works such as Karnak, Egypt, showcasing his engagement with Orientalist themes and ancient monuments. Views from Palestine capture the landscapes of the Holy Land. Closer to his adopted home, he painted scenes in England and Scotland, sometimes depicting the castles and country houses of his patrons, including possibly Chatsworth House for the Duke of Devonshire. A work titled Mentone, depicting the French Riviera town where he spent his final years and ultimately died, shows his continued activity late in life.

These works consistently demonstrate his strengths: fine draughtsmanship, luminous colour, and the ability to evoke a strong sense of place. Whether depicting the bustling canals of Venice or the serene ruins of ancient Egypt, Carelli offered his audience beautifully crafted visual souvenirs. His paintings served as more than mere records; they were artistic interpretations that captured the enduring appeal of these celebrated locations.

Context: The Victorian Art World and Beyond

Gabriele Carelli operated within the complex and dynamic art world of the nineteenth century. In Britain, his career unfolded alongside major movements like the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848 by artists such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt. Their detailed realism and morally charged subjects differed significantly from Carelli's picturesque landscapes, yet both catered to aspects of Victorian taste – one for narrative and symbolism, the other for travel and topography.

The influence of the critic John Ruskin (1819-1900) was pervasive. Ruskin championed Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites, advocating for truth to nature and meticulous observation. While Carelli was not directly associated with Ruskin's circle, his detailed topographical work arguably aligned with the Ruskinian emphasis on careful rendering of natural and architectural forms, albeit without the intense moral or spiritual overlay found in Pre-Raphaelite art.

Carelli's more traditional landscape style offered an alternative to the radical changes brewing in art towards the end of his career. Impressionism, pioneered by French artists like Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) – who both spent time in London – was beginning to challenge established modes of representation with its focus on fleeting light effects and subjective perception. Post-Impressionist artists like Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) and Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) were further deconstructing form and colour. Carelli remained largely untouched by these developments, continuing to practice in the accomplished topographical watercolour style that had brought him success.

Legacy and Conclusion: An Accomplished Topographical Master

Gabriele Carelli died in Menton on the French Riviera in 1900, concluding a long and productive career. He left behind a substantial body of work, primarily watercolours, that documents the landscapes and cities of Europe and the Middle East through the lens of a skilled nineteenth-century topographical artist. His legacy is multi-faceted. He represents an important link between the Neapolitan Posillipo School and the British art world, successfully transplanting his skills and adapting to a new environment.

He was part of a notable artistic family, with his father Raffaele, brother Consalvo, and later his own son, Conrad H. R. Carelli (active late 19th/early 20th century), all pursuing careers as painters. His work exemplifies the high level of technical accomplishment achieved in watercolour painting during the Victorian era. His popularity with patrons, including the Duke of Devonshire and Queen Victoria, attests to the appeal of his clear, bright, and meticulously rendered views.

While perhaps not an innovator on the scale of Turner or the Impressionists, Gabriele Carelli was a master craftsman within his chosen field. His watercolours provide valuable historical records of places, but more importantly, they are aesthetically pleasing works of art that continue to charm viewers with their luminosity and precision. He remains a respected figure among collectors and historians of nineteenth-century watercolour painting, an artist who skillfully captured the world he observed with elegance and enduring appeal.