George Earl (1824-1908) stands as a significant figure in the realm of British animal painting, particularly renowned for his masterful depictions of sporting dogs during the Victorian era. His work not only captures the physical likeness of these animals with remarkable accuracy but also provides a fascinating window into the social customs, sporting life, and even the technological advancements of his time. As an artist deeply embedded in the world he portrayed, Earl's canvases offer more than mere portraits; they are documents of a specific cultural moment.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Born in London in 1824, George Earl emerged from an environment steeped in artistic tradition. His father, Thomas Earl, was himself a painter, known for his depictions of sporting subjects and animals. This familial connection undoubtedly provided George with early exposure to the techniques and themes that would define his career. Growing up during a period of immense change in Britain – the height of the Industrial Revolution and the consolidation of the British Empire – Earl witnessed shifts in social structures, leisure activities, and the very landscape around him.

The Victorian era saw a burgeoning interest in the natural world, coupled with a passion for field sports among the landed gentry and increasingly, the affluent middle classes. Dog breeding became more formalized, with the establishment of breed standards and the rise of competitive dog shows. This cultural milieu created a fertile ground for artists specializing in animal portraiture, and George Earl was perfectly positioned to meet this demand. His training, likely initiated under his father and supplemented by self-study and observation, focused on achieving anatomical accuracy and capturing the vitality of his subjects.

The Victorian Fascination with Sporting Dogs

To fully appreciate George Earl's contribution, one must understand the context of animal painting in 19th-century Britain. While artists had depicted animals for centuries, the Victorian era saw a particular surge in the popularity of sporting and domestic animal portraits. This was driven by several factors: the romanticization of rural life and country pursuits, the pride taken in well-bred livestock and pets, and the aforementioned rise of organized dog breeding and showing.

Dogs, in particular, held a special place. Different breeds were associated with specific functions – hunting, retrieving, guarding – and often signified the status and interests of their owners. Commissioning a portrait of a prized pointer, setter, or retriever was a way for gentlemen to display their connection to the traditions of the field and their discerning taste in canine companions. Earl's focus on sporting dogs tapped directly into this cultural enthusiasm.

He worked during a time when other notable animal painters were active, creating a vibrant scene for this genre. Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) was perhaps the most famous, known for his often dramatic and anthropomorphized depictions of animals, such as the iconic "Monarch of the Glen." Richard Ansdell (1815-1885) was another prolific painter of animals and sporting scenes, often collaborating with landscape artists. John Frederick Herring Sr. (1795-1865) excelled in portraying horses, particularly racehorses and farm scenes, capturing their power and grace.

Compared to Landseer's sometimes sentimental approach, Earl's work often maintained a more straightforward, naturalistic focus, emphasizing the dog's physical attributes and working character. His detailed realism also set him apart from the slightly looser, more impressionistic style seen in the later works of artists like John Emms (1843-1912), who also specialized in hounds. Other contemporaries included Briton Rivière (1840-1920), known for his narrative paintings often featuring animals, and Heywood Hardy (1842-1933), who depicted sporting and historical scenes. The tradition was long-standing, looking back to earlier masters like Abraham Cooper (1787-1868) and James Ward (1769-1859), who were renowned for their animal and sporting art. Even the great French animal painter Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) found admirers in Britain. Within this context, George Earl carved his niche through meticulous observation and a clear affinity for the canine form.

Artistic Style and Technique

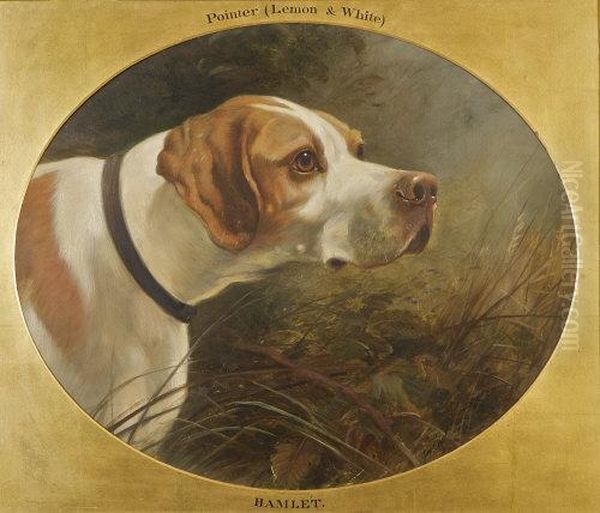

George Earl's style is characterized by its detailed realism and keen observational skill. He possessed a profound understanding of canine anatomy, allowing him to render dogs with convincing structure and posture, whether at rest or in motion. His brushwork was typically precise, capturing the varied textures of fur, the wetness of a nose, and the intelligent gleam in an eye. He paid close attention to the specific characteristics of different breeds, satisfying patrons who valued accuracy and breed standards.

Beyond mere anatomical correctness, Earl imbued his subjects with a sense of vitality and individual character. His dog portraits are rarely static; they often suggest alertness, eagerness, or the quiet composure of a well-trained animal. He achieved this through careful composition, subtle nuances of expression, and the skillful use of light and shadow to model form and create atmosphere. While primarily focused on the animals themselves, his backgrounds, whether simple studio settings or suggestive landscapes, were rendered competently to support the main subject without overwhelming it.

Unlike some contemporaries who might overly romanticize or humanize their animal subjects, Earl generally maintained a degree of objective representation, celebrating the dog for its natural form and function within the sporting world. This commitment to realism was particularly valued at a time before photography became a common tool for artistic reference in animal portraiture.

Masterworks: Chronicling the Canine World

George Earl produced a significant body of work throughout his long career, but several paintings stand out as particularly representative of his skill and thematic interests.

The Field Trial Meeting at Bala

Perhaps Earl's most ambitious and celebrated work is "The Field Trial Meeting at Bala, North Wales." This large-scale painting depicts a fictional gathering of prominent figures and their dogs involved in the sport of field trials – competitions designed to test the working abilities of gundog breeds like pointers and setters. Set against the backdrop of the Welsh landscape near Bala Lake, the painting is a veritable "who's who" of the mid-Victorian field trial scene.

Earl meticulously portrayed numerous recognizable dogs of the era, along with their owners and handlers. It serves as an invaluable historical document of the breeds, the people, and the sporting culture of the time. The composition is complex, managing a large number of figures and animals without sacrificing individual detail. The painting showcases Earl's ability to handle group portraiture on a grand scale while maintaining his characteristic focus on the accurate depiction of the dogs. This significant work is now housed in the collection of the AKC Museum of the Dog in New York, acquired through dedicated fundraising efforts, highlighting its enduring importance.

Champion Dogs of England

Reflecting the growing importance of dog shows and breed standards, George Earl undertook a project to paint portraits of notable champion dogs. This series, often compiled or reproduced in publications like "The Illustrated Book of the Dog" (circa 1879-81) by Vero Shaw, further cemented Earl's reputation as a leading canine artist. These portraits focused on individual animals, showcasing their conformation according to the developing breed standards promoted by organizations like The Kennel Club (founded in 1873).

These works emphasized the specific physical attributes that defined each breed, from the elegant lines of a Greyhound to the sturdy build of a Mastiff. They served not only as portraits of individual champions but also as visual guides to breed type, contributing to the codification and popularization of purebred dogs. This series demonstrates Earl's versatility in moving from the dynamic action of field scenes to the more formal requirements of breed-standard portraiture.

Going North and Coming South

Two of Earl's most intriguing works move beyond purely sporting scenes to capture a broader slice of Victorian life, incorporating the impact of modern technology. "Going North" (1893) and its companion piece "Coming South" (1895) depict scenes at Perth General Railway Station in Scotland. These paintings portray travelers, likely aristocrats and gentry, embarking on or returning from the sporting season in the Scottish Highlands.

"Going North" shows the platform bustling with activity as passengers, porters, and a multitude of dogs prepare to board a train. The scene captures the excitement and anticipation of the journey north for grouse shooting or deer stalking. Dogs of various breeds – setters, retrievers, terriers – are prominently featured, highlighting their essential role in these pursuits. The painting also subtly comments on the social hierarchy of the time, visible in the interactions between the wealthy travelers and the station staff.

"Coming South," painted two years later, depicts the return journey. The mood is perhaps slightly more subdued, the season over. Again, dogs are central to the scene. These paintings are significant not only for their depiction of sporting life but also for their representation of railway travel, a defining feature of the Victorian era that connected different parts of the country and facilitated activities like the annual migration to the Scottish sporting estates. "Going North" is preserved in the collection of the National Railway Museum in York, a testament to its importance as both art and social history. The original "Coming South" is believed to be lost or possibly painted over, adding a layer of mystery to this pair of works.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and the Earl Dynasty

George Earl's work was recognized within the established art institutions of his day. He exhibited paintings at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in London, including works shown in 1857, 1860, and 1882, bringing his specialized subject matter to a wider audience. His participation in such exhibitions placed him within the mainstream of the Victorian art world, even as he focused on a specific genre.

His legacy extends beyond his own canvases through his family. As mentioned, his father Thomas Earl was an artist. More significantly, his daughter, Maud Earl (1864-1943), followed in his footsteps and became an exceptionally successful and internationally renowned animal painter in her own right. Maud developed her own distinct style, often characterized by a slightly softer focus and perhaps a greater emphasis on the emotional connection between dogs and humans. She achieved considerable fame, particularly in Britain and America, receiving commissions from royalty and prominent figures. The Earl family thus represents a notable dynasty within the field of British animal painting, with George providing a crucial link and foundation. His brother, Percy Earl, was also reportedly an artist, further emphasizing the family's artistic inclinations, though George and Maud remain the most prominent figures.

The continued interest in George Earl's work is evident in museum collections and occasional exhibitions. The Kennel Club in the UK holds sketchbooks and other materials related to his work, occasionally featuring them in displays dedicated to canine art, such as their 2022 "Dog Paintings" exhibition. His paintings appear at auction, demonstrating an ongoing market appreciation for his skill and historical significance.

Society, Sport, and Artistry Intertwined

George Earl's paintings are more than aesthetically pleasing depictions of animals; they are cultural artifacts. They reflect the values and preoccupations of Victorian and Edwardian Britain. The emphasis on field sports speaks to the importance of rural traditions and land ownership, even as the nation rapidly industrialized. The meticulous rendering of purebred dogs mirrors the Victorian passion for classification, breeding, and competition that extended from horticulture to animal husbandry.

His railway paintings, "Going North" and "Coming South," explicitly engage with modernity, showing how technology facilitated traditional aristocratic pursuits. They capture the blend of old and new that characterized the era. The social dynamics depicted – the interactions between different classes on the station platform – offer glimpses into the structured society of the time. Through his chosen subject matter, Earl inadvertently became a social commentator, documenting the leisure activities and status symbols of the affluent classes.

While celebrated for his realism, it's worth noting that some discussion has occasionally arisen regarding the originality of certain compositions within the highly specialized and often replicated genre of sporting art, though Earl's primary reputation remains that of a skilled and respected practitioner. His dedication to his craft and his chosen subject matter provided a valuable visual record of the dogs and the sporting culture he knew so well.

Enduring Legacy

George Earl passed away in 1908, leaving behind a substantial legacy as one of Britain's foremost painters of sporting dogs. His career spanned a period of significant development in both the art world and the world of canine fancy. He captured the rise of breed standards, the popularity of field sports, and the essence of the dogs that were central to that culture. His work is valued not only for its artistic merit – the anatomical accuracy, the lifelike rendering, the skillful composition – but also for its historical importance.

His paintings provide invaluable insights into specific breeds as they appeared in the 19th century, the equipment and practices associated with field sports, and the social context in which these activities took place. He stands alongside other great animal artists like Landseer, Ansdell, Herring Sr., and later figures such as Arthur Wardle (1860-1949) and Wright Barker (1864-1941), as a key contributor to this genre.

Collected by major institutions like the National Railway Museum and the AKC Museum of the Dog, and admired by enthusiasts of canine history and sporting art, George Earl's work continues to resonate. He remains a testament to the enduring appeal of animal portraiture and a vital visual chronicler of the dogs and the society of Victorian Britain.