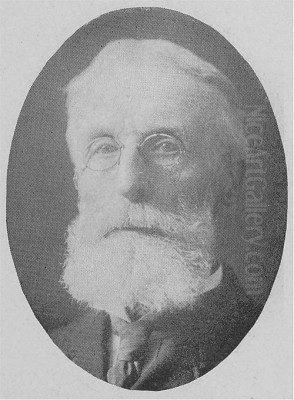

George Henry Smillie (1840-1921) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the transition of American landscape painting from the detailed realism of the Hudson River School to the brighter palettes and looser brushwork of Impressionism. His long and productive career saw him capture the diverse beauty of the American continent, from the tranquil coasts of New England to the majestic peaks of the Rockies, leaving behind an oeuvre that reflects both the artistic currents of his time and a deeply personal connection to the natural world.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Born in New York City on December 29, 1840, George Henry Smillie was immersed in art from his earliest years. His father, James Smillie (1807-1885), was a highly respected Scottish-born engraver who had immigrated to the United States and established a successful career. The elder Smillie was known for his meticulous skill in translating paintings, particularly landscapes by artists like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, into popular prints. This familial environment undoubtedly provided George and his older brother, James David Smillie (1833-1909), who also became a noted artist and engraver, with an early and profound exposure to artistic techniques and the burgeoning American art scene.

George Henry Smillie's initial artistic training was under his father's tutelage, where he would have learned the fundamentals of drawing and the precise art of engraving. This grounding in detailed representation would serve him well throughout his career, even as his style evolved. However, his aspirations lay in painting. To pursue this, in 1861, he sought formal instruction from James McDougal Hart (1828-1901). Hart, along with his brother William Hart, was a prominent member of the later Hudson River School, known for his pastoral landscapes imbued with a gentle, bucolic charm. Studying with Hart provided Smillie with a direct link to the dominant landscape tradition in America, emphasizing careful observation of nature, detailed rendering, and a reverence for the American wilderness.

The Hudson River School Influence

The Hudson River School, America's first true school of landscape painting, was at its zenith during Smillie's formative years. Artists like Thomas Cole, Asher B. Durand, Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, and Sanford Robinson Gifford had established a tradition of depicting the American landscape with a combination of realistic detail and romantic grandeur. Their works often celebrated the unique beauty and untamed wilderness of the continent, sometimes imbuing it with moral or nationalistic significance.

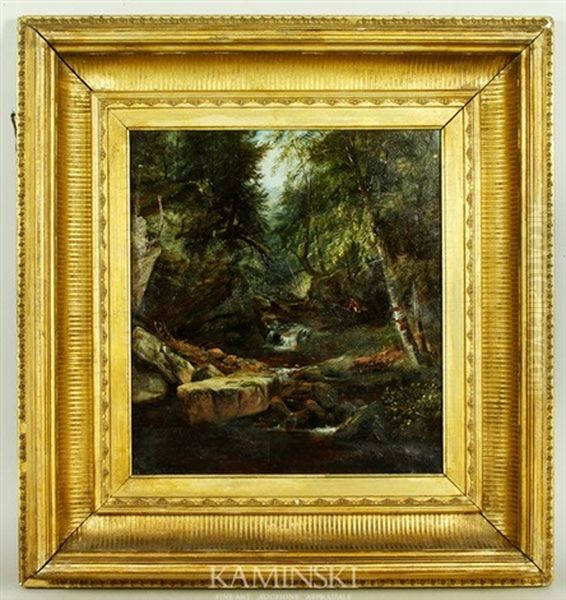

Smillie's early works clearly reflect the influence of this school and his training with James McDougal Hart. His paintings from the 1860s and early 1870s are characterized by a meticulous attention to detail, a smooth finish, and a faithful representation of specific locales. He, like many of his contemporaries, embarked on sketching trips to gather material, venturing into the scenic regions of New England, the Adirondack Mountains, and the White Mountains of New Hampshire. These expeditions were crucial for 19th-century landscape painters, allowing them to study nature firsthand and collect sketches that would later be developed into finished studio paintings.

His painting Trees and Meadows of Newburyport (1871) exemplifies this early phase. It showcases a careful rendering of foliage, a balanced composition, and a serene atmosphere typical of the Hudson River School's later, more pastoral manifestations. The light is clear and even, illuminating the scene with a quiet dignity.

A Career Takes Root in New York

New York City was the undisputed center of the American art world in the 19th century, and Smillie established his professional career there. He opened his own studio in 1862 and, in the same year, began exhibiting his work at the prestigious National Academy of Design. The Academy was a vital institution for American artists, providing exhibition opportunities, fostering a sense of community, and conferring status.

Smillie's talent was quickly recognized. He was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design (ANA) in 1864, a significant early milestone. He would later become a full Academician (NA) in 1882, a testament to his established reputation among his peers. His involvement with the Academy was substantial; he served as its Recording Secretary from 1892 to 1902 and later as Treasurer. These roles indicate not only his artistic standing but also his commitment to the institutional framework of the American art community.

Throughout his career, Smillie remained based in New York, but his artistic vision was fueled by extensive travel. He frequently journeyed throughout the eastern United States, particularly favoring the coastal areas of New England, such as Massachusetts and Maine, and Long Island. The varied light and atmospheric effects of the coastline became a recurring theme in his work. He also explored the interior, painting the landscapes of the Adirondacks and, significantly, venturing further afield.

Broadening Horizons: Travels West and to Europe

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Smillie sought out new and dramatic scenery. In 1871, he traveled with his brother James David Smillie to the American West, visiting the Rocky Mountains and Yosemite Valley in California. This journey exposed him to landscapes of a scale and grandeur far exceeding those of the East Coast. The towering peaks, vast canyons, and unique geological formations of the West had already captivated artists like Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran, who were producing epic canvases that thrilled audiences. Smillie's Western subjects, while perhaps not on the same monumental scale as Bierstadt's, captured the unique light and atmosphere of these regions.

Smillie also undertook trips to Europe, including one in 1884. European travel was considered essential for American artists, offering opportunities to study Old Masters, experience different cultures, and engage with contemporary European art movements. While the direct impact of specific European artists on Smillie's style from this period is not always explicitly documented in his subsequent work, the exposure to different artistic approaches, particularly the Barbizon School's emphasis on atmospheric effects and the burgeoning Impressionist movement, likely contributed to the gradual evolution of his style. Artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Charles-François Daubigny of the Barbizon School were widely admired in America for their poetic and evocative landscapes.

The American Watercolor Society and Other Affiliations

Beyond the National Academy of Design, George Henry Smillie was an active member of several other important art organizations. He was a prominent member of the American Watercolor Society (AWS), serving as its secretary from 1868 to 1873 and later as its treasurer. The AWS, founded in 1866, played a crucial role in elevating the status of watercolor painting in America, which had often been considered a medium for sketches rather than finished exhibition pieces. Smillie's involvement underscores his proficiency and interest in this medium. Winslow Homer, another master of watercolor, was also a key figure in the AWS, and their efforts helped to establish watercolor as a major form of American artistic expression.

Smillie also held memberships in the Century Association (sometimes referred to as the Century Club), the Lotos Club, and the Salmagundi Club, all important social and professional organizations for artists and art patrons in New York. These affiliations provided him with a network of colleagues, exhibition venues, and potential buyers, further integrating him into the fabric of the city's cultural life. He also exhibited at institutions like the Boston Art Club and the Brooklyn Art Association.

Marriage and Artistic Partnership

In 1881, George Henry Smillie married Nellie Sheldon Jacobs (1854-1926), an artist in her own right. Nellie had been a student of George's brother, James David Smillie, who taught at the National Academy of Design. The couple shared a studio in New York City for three decades, a testament to a supportive artistic and personal partnership. While Nellie Smillie (as she became known) developed her own career, primarily as a watercolorist and painter of floral still lifes and landscapes, their shared life and workspace suggest a mutual influence and understanding. Such artistic partnerships, while not uncommon, highlight a dedication to their craft that permeated their domestic life.

During a period of economic difficulty around 1893, a financial panic that affected many, George and Nellie traveled to Bar Harbor, Maine, seeking commissions. Despite the challenging circumstances, they spent two summers there, continuing their artistic pursuits. This anecdote reveals their resilience and commitment to their careers even in adverse times.

Stylistic Evolution: Towards a Lighter Palette

While Smillie's early work was firmly rooted in the Hudson River School tradition, his style underwent a noticeable transformation over the decades, gradually moving towards a more Impressionistic approach. This was not an abrupt shift but rather a progressive lightening of his palette, a loosening of his brushwork, and an increased interest in capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere.

This evolution was in keeping with broader trends in American art. By the 1880s and 1890s, American artists who had studied in Paris, such as Theodore Robinson, Childe Hassam, John Henry Twachtman, and J. Alden Weir, were returning to the United States and popularizing Impressionist techniques. While French Impressionism, with its emphasis on broken color and subjective visual sensations, was initially met with some resistance, its influence became undeniable.

Smillie's later works, particularly those from the 1880s onwards, show this influence. His brushstrokes become more visible and varied, contributing to a more textured surface. His colors become brighter and more luminous, capturing the vibrancy of sunlight on water or the delicate hues of a coastal haze. While he never fully abandoned the underlying structure and draftsmanship of his earlier training, his later paintings are less about meticulous detail and more about conveying an overall impression and an emotional response to the landscape. Works like Autumn on the Massachusetts Coast (1888) and East Hampton Meadows (1890) demonstrate this shift, with their brighter colors and more expressive handling of paint. Near Ridgefield (1892) and Mill Pond at Ridgefield (1892) also showcase this mature style, balancing descriptive accuracy with a more painterly and atmospheric quality.

His approach to Impressionism was perhaps more aligned with what is often termed "American Impressionism," which tended to retain a greater sense of form and solidity compared to its French counterpart, often blending Impressionist techniques with a lingering academic realism. Artists like William Merritt Chase also exemplified this American adaptation.

Notable Works and Recurring Themes

Throughout his long career, Smillie produced a substantial body of work. His subjects were diverse, yet certain themes and locations recurred, reflecting his personal affinities.

Coastal scenes of New England and Long Island were a particular forte. He was adept at capturing the interplay of light on water, the textures of sand dunes, and the atmospheric conditions of the seaside. Paintings like East Hampton Meadows (1890) are celebrated for their delicate finish and sensitive portrayal of the coastal landscape. The subtle gradations of color in the sky and water, and the gentle rhythm of the landscape, create a sense of tranquility and poetic beauty.

His depictions of pastoral inland scenes, often featuring gentle hills, meandering streams, and picturesque villages, also form an important part of his oeuvre. These works, such as Lake Scene (1880), evoke a sense of peace and harmony with nature, continuing the idyllic strain found in the work of his teacher, James M. Hart, but often infused with a brighter, more modern sensibility in his later period.

The more rugged landscapes of the Adirondacks and the White Mountains also provided him with inspiration. These paintings often convey a greater sense of wildness and natural grandeur, though Smillie's interpretations tend to be more intimate and less overtly dramatic than those of some of his Hudson River School predecessors like Bierstadt or Church.

His works are held in the collections of numerous prestigious institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Academy of Design, the Brooklyn Museum, the Oakland Museum of California, the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, and the Union League Club of Philadelphia, among others. This widespread institutional representation attests to the quality and significance of his contributions to American art.

The Smillie Artistic Family

It is worth noting again the artistic environment of the Smillie family. George Henry Smillie was not an isolated talent but part of a lineage. His father, James Smillie, was a master engraver whose work helped disseminate American landscape art to a wider public. His brother, James David Smillie, was also a highly accomplished artist, proficient in both engraving and painting, and a respected teacher. James D. Smillie was also deeply involved in the National Academy of Design and the American Watercolor Society. This family context of shared artistic endeavor and mutual support likely played a significant role in George Henry Smillie's development and sustained career. The Smillies, as a family, made a notable contribution to the 19th-century American art scene, particularly in the realms of landscape and printmaking.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

George Henry Smillie continued to paint and exhibit actively into the early 20th century. He maintained his studio in New York City, a familiar figure in its art circles. His style, while evolving, retained a consistent quality and a deep appreciation for the American landscape. He passed away in Bronxville, New York, on November 10, 1921, at the age of 80.

In art historical terms, George Henry Smillie is recognized as a skilled and versatile landscape painter who successfully navigated the changing artistic tides of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He began his career firmly within the Hudson River School tradition, mastering its techniques of detailed realism and reverential depiction of nature. As new influences, particularly Impressionism, arrived from Europe, he adapted his style, incorporating brighter colors and more expressive brushwork without entirely abandoning his foundational training.

His work provides a valuable link between these two major movements in American art. He was a contemporary of artists who remained more steadfastly in the Hudson River School tradition, like Sanford Robinson Gifford or John Frederick Kensett in their later years, and also of the pioneering American Impressionists like Childe Hassam and Theodore Robinson. His oeuvre reflects this transitional period, showcasing an artist who was open to new ideas while remaining true to his own vision.

Smillie's dedication to art organizations like the National Academy of Design and the American Watercolor Society also highlights his role as a significant contributor to the professionalization and development of the American art world. His long service to these institutions helped shape the environment in which American artists worked and exhibited.

Conclusion

George Henry Smillie's legacy is that of a dedicated and accomplished landscape painter who captured the multifaceted beauty of America with sensitivity and skill. From the meticulously rendered scenes of his early career to the more luminous and atmospheric works of his maturity, his paintings offer a visual journey through the evolving aesthetics of American art. He was a respected member of the artistic community, a bridge between traditions, and an artist whose deep affection for the natural world shines through in his enduring body of work. While perhaps not always accorded the same level of fame as some of his more revolutionary contemporaries, George Henry Smillie remains an important figure whose contributions enrich our understanding of American landscape painting in a pivotal era of its development. His paintings continue to be admired for their technical proficiency, their evocative beauty, and their heartfelt celebration of the American scene.