Giulio Cesare Vinzio (1881-1940) stands as a noteworthy figure in the rich tapestry of early twentieth-century Italian art. An accomplished painter, Vinzio's career unfolded during a period of significant artistic transition, where the echoes of nineteenth-century traditions met the burgeoning waves of modernism. Born in Livorno, a city with a vibrant artistic heritage, and later working primarily in Milan, Vinzio's oeuvre is characterized by a profound engagement with landscape painting, a sensitive handling of light, and an evolving style that reflected the dynamic artistic currents of his time. While perhaps not as globally renowned as some of his more radical contemporaries, Vinzio's work offers a valuable lens through which to understand the nuanced development of Italian painting, particularly the legacy of the Macchiaioli and the advent of Divisionism and later, the Novecento Italiano.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Livorno

Giulio Cesare Vinzio was born in Livorno, Tuscany, in 1881. This coastal city was not merely a picturesque backdrop but a crucible of artistic innovation in Italy, particularly during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Livorno was a key center for the Macchiaioli, a group of painters who, in a manner analogous to the French Impressionists, broke from academic conventions to paint outdoors, capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere through "macchie" or patches of color. The artistic air in Livorno was thus charged with a spirit of naturalism and a focus on direct observation.

It was in this environment that Vinzio received his foundational artistic training. Crucially, he became a student at the private art school run by Guglielmo Micheli. Micheli (1866-1926) was himself a significant painter and a former pupil of the great Macchiaioli master, Giovanni Fattori (1825-1908). Fattori's influence, with his powerful depictions of Tuscan landscapes, military scenes, and rural life, permeated Micheli's teaching and, consequently, the early development of his students. Micheli's school, active from the late 1880s, became a vital hub for aspiring artists in Livorno.

At Micheli's school, Vinzio was part of a talented cohort of young painters who would go on to make their own marks on Italian art. Among his fellow students were figures such as Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920), who would later achieve international fame in Paris for his distinctive portraits and nudes; Llewelyn Lloyd (1879-1949), a painter of Welsh descent who became deeply integrated into the Tuscan art scene; Oscar Ghiglia (1876-1945), known for his introspective still lifes and portraits; Gino Romiti (1881-1967), another dedicated landscape painter; Renato Natali (1883-1979), celebrated for his vibrant depictions of Livorno's streets and nightlife; and Manlio Martinelli (1884-1974). This shared formative experience under Micheli fostered a collegial atmosphere, even as each artist began to forge their individual path.

The Influence of the Micheli School: Divisionism and Beyond

Guglielmo Micheli's pedagogy, while rooted in the Macchiaioli tradition of en plein air painting and truth to nature, was also open to contemporary European artistic developments. One of the most significant of these was Divisionism (or Pointillisme as it was known from its French origins with Georges Seurat and Paul Signac). Divisionism, which involved applying color in small, distinct dots or strokes that were intended to blend optically in the viewer's eye, gained considerable traction in Italy towards the end of the nineteenth century. Italian Divisionists like Giovanni Segantini (1858-1899), Gaetano Previati (1852-1920), Angelo Morbelli (1853-1919), and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo (1868-1907) adapted the technique to explore themes ranging from rural labor and social commentary to Symbolist allegories, often imbuing their work with a unique luminosity and emotional intensity.

The young artists at Micheli's school, including Vinzio, were receptive to these new ideas. Evidence suggests that Vinzio, in his early phase, leaned towards a Divisionist approach. This stylistic choice allowed for a more scientific and vibrant rendering of light and atmosphere, particularly suited to landscape painting. The meticulous application of color, characteristic of Divisionism, would have offered a new way to capture the sun-drenched Tuscan countryside that was a frequent subject for these artists. The collective exploration of Divisionism within the Micheli circle marked an important step beyond the more direct, albeit still revolutionary, brushwork of the foundational Macchiaioli painters like Silvestro Lega (1826-1895) or Telemaco Signorini (1835-1901).

However, the artistic journey for Vinzio and his peers did not end with Divisionism. As the early twentieth century progressed, Italian art saw a complex interplay of styles. The legacy of the Macchiaioli continued to evolve into what is sometimes termed Post-Macchiaioli, where the emphasis on light and direct observation remained, but often with a greater simplification of form or a more subjective interpretation of color. Vinzio's work appears to have navigated this terrain, gradually moving from a more orthodox Divisionist application towards other stylistic expressions that characterized the early decades of the new century.

Vinzio's Artistic Style: Landscapes, Light, and Technique

Giulio Cesare Vinzio's primary artistic focus throughout his career was landscape painting. His works often depict serene countryside vistas, rural pathways, glimpses of villages, and the characteristic churches that dot the Italian landscape. These subjects reflect a deep connection to his native Tuscany and later, perhaps, to the Lombard countryside around Milan, where he eventually settled and worked. His paintings evoke a sense of tranquility and an appreciation for the enduring beauty of the Italian terrain.

His technique, rooted in oil painting, evolved over time. While his early works showed a clear affinity for Divisionist principles, aiming to capture the vibrancy of light through fragmented color, his later paintings might have incorporated broader strokes and a more synthesized approach to form, aligning with the general trend away from strict Divisionism towards more personal interpretations. The provided information notes that he often signed his works on the frame, a detail that, while not uncommon, can sometimes indicate a particular attention to the presentation of the artwork as a complete object.

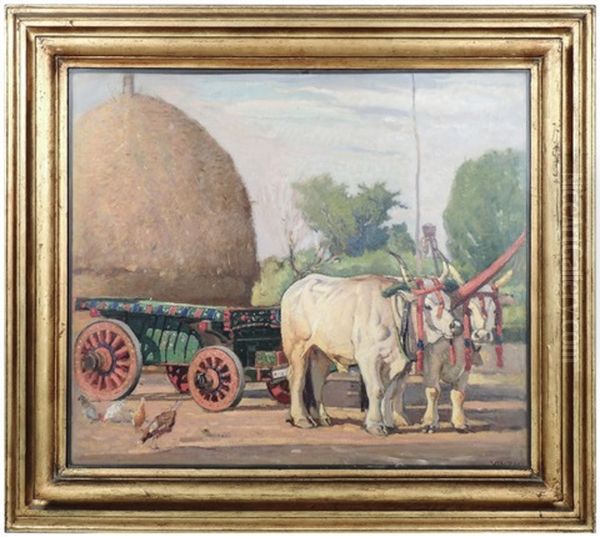

The themes in Vinzio's art are consistent with a painter deeply observant of his environment. Works such as Paesaggio di campagna con scorcio di chiesa (Countryside Landscape with a Glimpse of a Church) directly point to his interest in the interplay between nature and human presence, often symbolized by architectural elements like a village church. Similarly, Scorciaia con contadina (Shortcut with Peasant Woman) and Paesaggio di campagna con carretto (Countryside Landscape with Cart) suggest an engagement with scenes of everyday rural life, a theme with strong roots in nineteenth-century Italian realism and the Macchiaioli tradition. These subjects allowed Vinzio to explore the changing effects of light on different textures and forms, from the foliage of trees and the undulation of fields to the rustic surfaces of buildings and the figures within the landscape.

Notable Works and Exhibitions

Several specific works by Giulio Cesare Vinzio help to illustrate his artistic concerns and achievements. The aforementioned landscape titles, Paesaggio di campagna con scorcio di chiesa, Scorciaia con contadina, and Paesaggio di campagna con carretto, are indicative of his primary thematic interests. These paintings, likely executed with his characteristic sensitivity to light and atmosphere, would have showcased his ability to render the Italian countryside with both accuracy and poetic feeling.

His Self-Portrait, which was exhibited at the Galleria d'Arte Moderna in Milan, offers a glimpse into another facet of his work. Self-portraiture provides artists with an opportunity for introspection and a display of technical skill in capturing likeness and character. Its inclusion in a prominent Milanese gallery suggests a degree of recognition within the art establishment of that city.

Another work, Carro con buoi (Cart with Oxen), was exhibited at the Galleria Pesaro in Milan. This subject, featuring working animals and a cart, is a classic theme in rural genre painting, again echoing the interests of artists like Giovanni Fattori. The Galleria Pesaro, under the direction of Lino Pesaro, was an important venue for contemporary artists in Milan during the early to mid-twentieth century, known for promoting a variety of artistic tendencies, including those associated with the Novecento Italiano movement. Vinzio's correspondence with Gastone Razzagutti, a curator associated with Galleria Pesaro, regarding artistic discussions and economic matters, further underscores his active participation in the Milanese art world.

Vinzio also participated in group exhibitions, such as one held at Villa La Versiliana in Marina di Pietrasanta, which specifically featured painters from the Micheli school. Such exhibitions were crucial for fostering a sense of shared identity among artists from a particular school or movement and for bringing their work to a wider public. The description of his work in a Livorno exhibition as having "surprising, commendable linguistic value" indicates positive critical reception and an acknowledgment of his distinct artistic voice.

The Broader Artistic Context: Navigating Italian Modernism

To fully appreciate Giulio Cesare Vinzio's artistic journey, it is essential to consider the broader context of Italian art during his lifetime. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were a period of intense artistic ferment in Italy. The Macchiaioli had already challenged academic norms. Divisionism, as discussed, brought a new scientific and often symbolic approach to painting.

Simultaneously, other movements were emerging. Futurism, launched by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's manifesto in 1909, exploded onto the scene with its radical embrace of modernity, speed, technology, and a complete rejection of past traditions. Artists like Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916), Giacomo Balla (1871-1958), Carlo Carrà (1881-1966), Luigi Russolo (1885-1947), and Gino Severini (1883-1966) championed a dynamic, fragmented vision of the world. While Vinzio's art does not appear to align with Futurist aesthetics, the movement's pervasive energy transformed the Italian art landscape.

Following the upheavals of World War I and the avant-garde experiments, the 1920s saw the rise of the "Return to Order" across Europe. In Italy, this manifested significantly in the Novecento Italiano movement, officially launched in 1922 under the patronage of art critic Margherita Sarfatti and, to some extent, with the support of Benito Mussolini's Fascist regime. The Novecento advocated for a return to classical Italian artistic traditions, emphasizing solid form, clear composition, and skilled craftsmanship, as a reaction against the perceived excesses of the avant-garde. Key figures associated with the Novecento included Mario Sironi (1885-1961), Achille Funi (1890-1972), Anselmo Bucci (1887-1955), Leonardo Dudreville (1885-1976), Ubaldo Oppi (1889-1942), and Piero Marussig (1879-1937).

Given that Vinzio was active in Milan, a major center for the Novecento, and that his style evolved beyond strict Divisionism towards "other 20th-century styles," it is plausible that his later work may have absorbed some of the Novecento's emphasis on clarity and structured composition, while still retaining his personal focus on landscape. The information that the Micheli school artists, after their Divisionist phase, "gradually simplified in form, entering the Post-Macchiaiolo style" and then moved towards "20th-century other styles" including Novecento, supports this potential trajectory for Vinzio. His art likely represented a more moderate path, one that valued traditional genres like landscape and skilled execution, while subtly incorporating contemporary stylistic refinements.

Connections and Contemporaries Revisited

Vinzio's connection with Amedeo Modigliani during their student days in Livorno is particularly intriguing. While Modigliani's path led him to Paris and a highly idiosyncratic style that blended influences from African sculpture, Renaissance portraiture, and contemporary avant-garde movements, their shared foundation under Micheli highlights the diverse outcomes that could spring from a common artistic education. Modigliani's meteoric rise and tragic early death have cemented his legendary status, but it's valuable to remember the network of artists, like Vinzio, who were part of his formative years.

The continued association with other Micheli alumni, such as Llewelyn Lloyd, Gino Romiti, and Renato Natali, suggests a lasting bond forged in their youth. These artists, while developing individual styles, often shared a commitment to depicting the Tuscan landscape and a certain fidelity to the principles of light and direct observation inherited from the Macchiaioli and filtered through their experiments with Divisionism. For instance, Lloyd became known for his luminous depictions of the Tuscan coast and countryside, while Natali remained a beloved chronicler of Livorno's vibrant urban life. Oscar Ghiglia, another contemporary from Micheli's school, developed a distinct style characterized by its formal rigor and psychological depth, particularly in his still lifes, drawing comparisons to Cézanne.

Vinzio's interactions within the Milanese art scene, evidenced by his exhibitions at the Galleria d'Arte Moderna and Galleria Pesaro, and his correspondence with figures like Gastone Razzagutti, place him within the professional art circles of one of Italy's most dynamic cities. Milan was a hub for artistic debate and commerce, and Vinzio's presence there indicates his active participation in this environment.

Legacy and Conclusion

Giulio Cesare Vinzio passed away in 1940. His artistic career spanned a period of profound transformation in Italian art and society. He emerged from the strong landscape tradition of Livorno, deeply influenced by the Macchiaioli legacy through his teacher Guglielmo Micheli. He embraced the modern technique of Divisionism, using it to explore the effects of light and color in his beloved Italian landscapes. As artistic tastes evolved, so too did Vinzio's style, likely reflecting the broader currents of early twentieth-century Italian painting, including the formal simplifications of Post-Macchiaioli approaches and potentially the classicizing tendencies of the Novecento.

While he may not have achieved the same level of international fame as some of his contemporaries like Modigliani or the leading Futurists, Vinzio's contribution is significant. He represents a dedicated and skilled painter who remained committed to the genre of landscape, interpreting it with sensitivity and an evolving technical mastery. His works offer a window into the regional artistic scenes of Livorno and Milan, and his career exemplifies the journey of an artist navigating the complex transition from nineteenth-century naturalism to the diverse expressions of modernism.

The continued appearance of his works in auctions, such as a landscape painting noted with a starting bid of 300 Euros, indicates an ongoing, albeit perhaps modest, market interest and appreciation for his art. For art historians and enthusiasts, Giulio Cesare Vinzio remains a figure worthy of attention, a painter whose canvases capture the enduring beauty of the Italian landscape and reflect the artistic spirit of a pivotal era. His dedication to his craft and his nuanced engagement with the artistic currents of his time secure his place within the narrative of modern Italian art.