Hanna (Hirsch) Pauli stands as a significant figure in late 19th and early 20th-century Swedish art. A painter renowned for her insightful portraits, intimate domestic scenes, and a commitment to Realism, she navigated the evolving art world of her time with determination and skill. Born in Stockholm in 1864 and passing away in the same city in 1940, Pauli's life and career spanned a period of profound artistic and social change, which she both reflected and contributed to through her compelling body of work. Her artistic journey took her from the traditional academies of Stockholm to the vibrant, avant-garde atmosphere of Paris, shaping a style that was both deeply personal and resonant with the broader currents of European art.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Hanna Hirsch was born on January 13, 1864, in Stockholm, Sweden, into a culturally engaged Jewish family. Her father, Abraham Hirsch, was a prominent music publisher, and her mother was Pauline Meyerson. This environment likely fostered an early appreciation for the arts. Her innate talent for drawing and painting became evident at a young age, and by the age of twelve, she began her formal artistic training under the guidance of August Malmström. Malmström was a respected figure in Swedish art, known for his historical paintings and illustrations, and his tutelage would have provided a solid foundation in academic techniques.

This early education in Stockholm was crucial, but like many ambitious artists of her generation, Hirsch recognized the need to seek further training and exposure in Paris, which was then the undisputed capital of the art world. The allure of its academies, salons, and the dynamic community of international artists drew her, like a magnet, towards new horizons of artistic development.

Parisian Years and Formative Influences

Between 1885 and 1887, Hanna Hirsch immersed herself in the artistic crucible of Paris. She enrolled at the Académie Colarossi, a progressive private art school that was notably more welcoming to female students than the official École des Beaux-Arts. The Académie Colarossi was a popular choice for Scandinavian artists, and it was here that Hirsch honed her skills under painters such as Raphaël Collin and Gustave Courtois. Both Collin and Courtois were accomplished artists associated with the academic tradition but also open to the nuances of Naturalism that were gaining traction.

During her time in Paris, Hirsch became part of a lively circle of Nordic artists. Among them was the Finnish painter Venny Soldan (later Soldan-Brofeldt), who became a close friend and studio mate. This period was not just about technical training; it was an immersion in new ideas and artistic debates. She, along with many of her Scandinavian peers, became associated with the "Opponents" (Opponenterna), a group of Swedish artists who, in 1885, protested against the conservative principles of the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts and advocated for reforms in art education and exhibition opportunities. This rebellious spirit and desire for modernization in art were characteristic of the era.

The Parisian art scene was a melting pot of styles, from the lingering influence of academic art to the radical departures of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. While Hirsch absorbed these influences, her own inclinations leaned towards a carefully observed Realism, often infused with the detailed observation characteristic of Naturalism, a movement championed by figures like Jules Bastien-Lepage, whose work was highly admired by many Scandinavian artists.

Marriage and a Dual Career

In 1887, a pivotal year, Hanna Hirsch married the Swedish painter Georg Pauli. Georg was also an artist of considerable note, as well as an influential writer and art critic. Their union was a partnership of both life and art. After their marriage, Hanna adopted the surname Pauli. The couple returned to Sweden, initially settling in Stockholm, and later building a home, Villa Pauli, in Nacka, which became a gathering place for artists and intellectuals.

For Hanna Pauli, marriage and motherhood (they had three children) did not mean an end to her artistic career, a common fate for many women artists of the period. She managed to balance the demands of family life with her unwavering commitment to her painting. This was a testament to her determination and the supportive nature of her relationship with Georg, who himself was exploring various artistic styles, including Symbolism and monumental art. Hanna, however, largely remained dedicated to her Realist and Naturalist approach, focusing on figurative work, particularly portraits and genre scenes. She also took on a teaching role for a period at an art school in Gothenburg.

Artistic Style: Realism, Naturalism, and the "Juste Milieu"

Hanna Pauli's artistic style is primarily characterized by Realism, with strong elements of Naturalism. She sought to depict the world around her with honesty and accuracy, paying close attention to detail, light, and texture. Her approach was more aligned with the French "juste milieu" (middle way) painters, who sought a balance between academic tradition and modern Realist tendencies, rather than the fleeting light effects and broken brushwork of the Impressionists. Artists like Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret or the aforementioned Bastien-Lepage represent this tendency.

Pauli often employed a technique of applying paint thickly, using impasto to build up surfaces and convey the materiality of objects and the play of light. This technique, while effective, was sometimes misunderstood by contemporary critics. One anecdote suggests that some critics, puzzled by the texture of her canvases, even speculated that she might have wiped her brushes on them. In reality, it was a deliberate method to achieve specific visual effects, particularly in rendering the textures of fabrics, the sheen of surfaces, or the subtle gradations of light in an interior.

Her palette was often subdued, favoring naturalistic colors that enhanced the sense of verisimilitude in her scenes. While some of her later works show a slight engagement with Symbolist undertones, particularly in the mood or psychological depth of her portraits, her core commitment remained to the observable world. She was less interested in the radical formal experiments of artists like Paul Cézanne or the expressive color of Vincent van Gogh, and more in line with the Scandinavian tradition of Realism seen in the works of artists like P.S. Krøyer or Michael Ancher, though her focus was often more intimate and interior-based.

Masterpiece: "Breakfast Time" (Frukostdags)

Perhaps Hanna Pauli's most celebrated work is Breakfast Time (Frukostdags), painted in 1887. This masterpiece, now housed in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, exemplifies her artistic strengths. The painting depicts an outdoor breakfast scene, likely set in the garden of the Pauli family. Light filters through the leaves, dappling the white tablecloth and the figures gathered around it. The scene is imbued with a sense of quiet domesticity and tranquil beauty.

The composition is carefully arranged, yet it feels natural and unposed. Pauli's skill in rendering different textures is evident: the crispness of the linen, the gleam of silverware, the transparency of glass, and the lushness of the surrounding foliage. The play of light is particularly masterful, capturing the bright, yet soft, illumination of a summer morning. The figures are portrayed with a gentle intimacy, suggesting familial bonds and shared moments.

Breakfast Time was well-received and is considered a quintessential example of Nordic Naturalism. It captures a specific moment in time with a sense of immediacy and warmth, reflecting the late 19th-century bourgeois ideal of family life and the appreciation for nature and outdoor living. It stands alongside works by contemporaries like Carl Larsson in its depiction of Swedish domestic life, though Pauli's approach is generally less idealized and more grounded in observed reality than Larsson's charming, decorative style.

The "New Woman" in Portraiture: Venny Soldan-Brofeldt

Another highly significant work from this period is Pauli's Portrait of the Finnish Artist Venny Soldan-Brofeldt (1886-1887), now in the Gothenburg Museum of Art. This portrait is remarkable for its unconventional depiction of a female artist. Soldan-Brofeldt is shown in her Paris studio, not in elegant attire as was common for female portraits, but in a practical working smock, seated somewhat informally on the floor, engrossed in her work with clay. Her expression is serious and focused.

This portrayal challenged contemporary conventions of how women, especially female artists, should be represented. It presented Soldan-Brofeldt as a dedicated professional, a "New Woman" actively engaged in her creative pursuits. The directness of her gaze and the unpretentious setting speak to a modern sensibility. The painting was exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1887, where it garnered attention for its bold and honest portrayal. It reflects the growing assertiveness of women artists and their desire to be recognized for their professional capabilities rather than merely their social graces. This work can be seen in dialogue with other portraits of assertive women by artists like Édouard Manet or later, by Romaine Brooks.

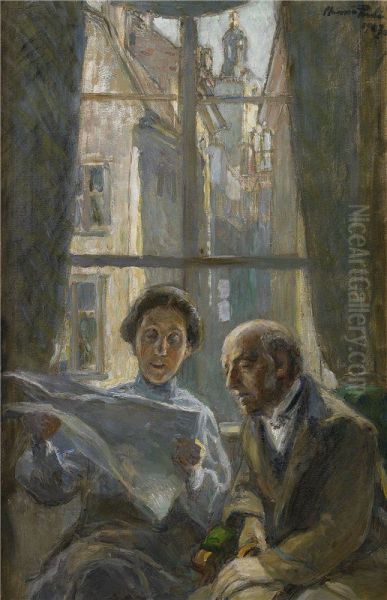

"Friends" (Vännerna / Kamrater) and the Intimacy of Female Bonds

A later, but equally important, painting is Friends (Vännerna or Kamrater), completed between 1900 and 1907, also in the Nationalmuseum. This large canvas depicts a group of women, including the prominent writer Ellen Key, engaged in conversation around a lamplit table in an evening interior. The atmosphere is one of intellectual engagement and intimate camaraderie. The figures are absorbed in their discussion, their faces illuminated by the warm lamplight, creating a sense of enclosure and shared confidence.

The painting is a powerful representation of female friendship and intellectual life. Ellen Key, a leading feminist and social critic, is a central figure, suggesting the progressive ideas that might have animated such gatherings. Pauli herself was part of intellectual circles that discussed socialism, pacifism, education, and art, often with figures like Key or her close friend Eva Bonnier. Friends captures the spirit of these modern women, who were forging new roles for themselves in society and culture. The careful rendering of the interior, the interplay of light and shadow, and the psychological acuity in the portrayal of the figures make this a compelling and historically significant work. A study for this painting, dated 1903, is also in the Nationalmuseum's collection.

Themes and Subjects: Portraits, Domesticity, and Social Observation

Throughout her career, Hanna Pauli focused on figurative subjects. Portraiture was a significant part of her oeuvre. She painted portraits of family members, friends, and notable contemporaries. Her portraits are characterized by their psychological insight and their ability to capture the sitter's personality. Examples include her portrait of her sister, Betty Hirsch (1900), and Georg Pauli's portrait of Hanna herself, which offers a glimpse into their artistic and personal relationship.

Domestic scenes, like Breakfast Time, were another recurring theme. These paintings often depicted quiet moments of family life, imbued with a sense of warmth and intimacy. They reflect the late 19th-century interest in everyday life and the private sphere, but Pauli's depictions avoid sentimentality, grounding them in careful observation.

Her work also touched upon social observation, particularly concerning the role of women. Paintings like the portrait of Venny Soldan-Brofeldt and Friends highlight the changing status of women and their engagement in artistic and intellectual pursuits. As a Jewish woman in a predominantly Christian society, and as a female artist in a male-dominated art world, Pauli's own experiences likely informed her sensitivity to issues of identity and social dynamics. There's an anecdote about her feeling a particular connection with a Moroccan Jewish model at the Académie Colarossi, a bond that transcended class and cultural differences, suggesting her awareness of these complex intersections.

Relationships and Artistic Circles

Hanna Pauli's life and career were interwoven with a rich network of artistic and intellectual relationships. Her marriage to Georg Pauli was a central partnership. While their artistic styles diverged over time—Georg moved towards Symbolism and monumental frescoes, influenced by artists like Puvis de Chavannes—they shared a deep commitment to art.

Her friendship with Eva Bonnier, daughter of the publisher Albert Bonnier and an accomplished painter herself, was particularly important. They were contemporaries, studied together in Paris, and shared artistic aspirations. Their correspondence reveals a close bond and mutual support. Both women navigated the challenges of being female artists in their era, striving for professional recognition.

Pauli also interacted with other leading Scandinavian artists. She is known to have sketched landscapes in the forest with Anders Zorn, one of Sweden's most famous painters, and his wife Emma Zorn. These interactions indicate her engagement with the broader artistic community and her interest in different aspects of artistic practice, including plein-air painting.

The intellectual discussions she participated in, often involving figures like Ellen Key or Eva Bonnier's brother, the philosopher and social theorist Carl Karlson, and his artist wife Lisen Bonnier (née Josephson, sister of artist Ernst Josephson), broadened her perspectives on social issues, which subtly informed her art. These circles were often progressive, discussing topics like pacifism, education reform, and women's rights.

Personal Life: Balancing Art and Family

Hanna Pauli's ability to maintain a professional artistic career while raising a family was noteworthy for her time. Many women artists found their careers curtailed by domestic responsibilities. Pauli, however, continued to paint and exhibit throughout her life. This required considerable dedication and likely a supportive domestic environment.

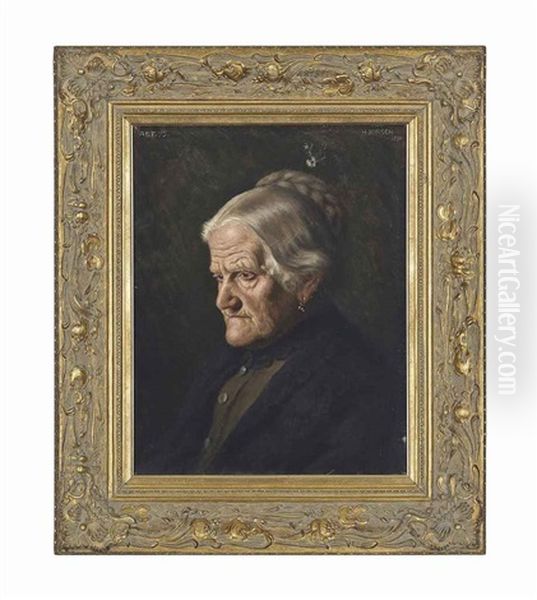

Anecdotes from her life offer glimpses into her working process and personality. For instance, she reportedly experienced frustration and even headaches when a model, an old woman, failed to hold a pose or express the desired character for a painting. This highlights the practical challenges of portraiture and her commitment to achieving a specific artistic vision. Her Jewish identity, while not always overtly present in her subject matter, formed part of her personal and social context, placing her in what has been described as an "in-between space" in certain social milieus.

Later Career, Legacy, and Collections

Hanna Pauli continued to work and exhibit into the 20th century, though her output was not as prolific as some of her contemporaries. Her dedication to a Realist-Naturalist aesthetic meant that as Modernist movements like Cubism and abstract art gained prominence, her style might have appeared more traditional. However, the quality and integrity of her work ensured its lasting value.

Her paintings are held in major Swedish museum collections. The Nationalmuseum in Stockholm holds several of her most important works, including Breakfast Time, Friends, and Study for Friends. The Gothenburg Museum of Art houses the iconic Portrait of Venny Soldan-Brofeldt. Other works, such as Blondin (1897) and The Artist's Sister (Betty Hirsch) (1900), are in other public and private collections, including the Hedda and N.D. Qvist Fund. Her works have also been featured in exhibitions at institutions like the Svensk-Franska Konstgalleriet (Swedish-French Art Gallery) in Stockholm.

Hanna Pauli passed away on December 29, 1940, in Stockholm, at the age of 76. Her legacy is that of a skilled and insightful painter who made significant contributions to Swedish art. She excelled in capturing the nuances of human character and the quiet beauty of everyday life. Her portrayals of women, in particular, offer valuable insights into the changing social roles and aspirations of women at the turn of the 20th century.

Conclusion: An Enduring Contribution

Hanna (Hirsch) Pauli remains an important figure in the narrative of Swedish and Nordic art. Her commitment to Realism, her technical skill, and her ability to imbue her subjects with psychological depth and quiet dignity distinguish her work. In an era of artistic ferment, she carved out a distinct path, creating a body of work that is both a reflection of her time and timeless in its human appeal. From the sun-dappled intimacy of Breakfast Time to the professional assertion of the Portrait of Venny Soldan-Brofeldt and the intellectual camaraderie of Friends, Hanna Pauli's paintings offer a rich and nuanced vision of the world she inhabited, securing her place as one of Sweden's most respected painters of her generation. Her art continues to resonate, admired for its honesty, craftsmanship, and profound humanism.