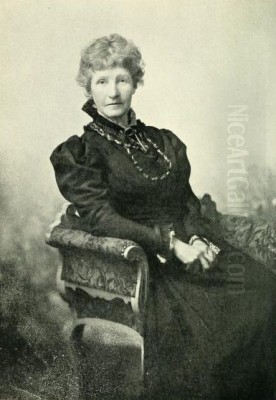

Helen Mary Elizabeth Allingham, born Paterson, stands as one of the most beloved and accomplished figures in British watercolour painting. Active during the latter half of the Victorian era and into the early twentieth century (1848-1926), she captured the idyllic charm and quiet beauty of the English countryside, particularly its humble cottages and blooming gardens, with a sensitivity and skill that resonated deeply with her contemporaries and continues to enchant viewers today. More than just a painter of picturesque scenes, Allingham was a pioneer for women artists, a successful illustrator, and a chronicler of a rural way of life that was steadily disappearing even in her own time.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Helen Paterson was born on September 26, 1848, in Swadlincote, Derbyshire. Her family background was steeped in both medicine and the arts. Her father, Alexander Henry Paterson, was a respected country doctor, while her mother, Mary Herford Paterson, nurtured a cultured home. Crucially, artistic talent ran in the family; her maternal grandmother, Sarah Smith Herford, and her aunt, Laura Herford, were both accomplished artists. Laura Herford, in particular, was a trailblazer, having famously gained admission to the Royal Academy Schools by submitting work signed simply "L. Herford," thus obscuring her gender until acceptance was granted.

This familial environment undoubtedly fostered Helen's innate artistic abilities from a young age. Tragedy struck early, however, when her father and one of her sisters died during a diphtheria epidemic in 1862. Following this loss, the remaining family moved to Birmingham to be closer to relatives. It was here that Helen's formal art education began, attending the Birmingham School of Design. Her talent was evident, and the desire for more advanced training soon led her to the heart of the British art world: London.

London Training and Formative Influences

In 1867, Helen moved to London to further her studies. She enrolled at the National Art Training School, specifically the Female School of Art, which later became part of the Royal College of Art. She also attended the prestigious Royal Academy Schools, following in her aunt Laura's footsteps. This period was crucial for her development, exposing her to the prevailing artistic currents and allowing her to hone her technical skills.

During her training, Allingham came under the influence of several prominent artists whose styles would leave a lasting impression on her own. Frederick Walker, known for his blend of classical composition with rustic realism, particularly in watercolour, was a significant inspiration. His idyllic yet unsentimental depictions of rural life resonated with her own inclinations. Another key figure was Sir John Everett Millais, one of the founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. While Allingham did not adopt the intense detail and symbolic complexity of early Pre-Raphaelitism, Millais's later work, often featuring evocative landscapes and sensitive portrayals, likely informed her approach to capturing mood and atmosphere. The broader influence of figures like John Ruskin, the pre-eminent art critic who championed truth to nature and detailed observation, also permeated the artistic environment in which she trained.

Success as an Illustrator

Before dedicating herself fully to watercolour painting, Helen Paterson established a successful career as a professional illustrator. This was a practical necessity for a young woman seeking financial independence, and she quickly proved adept in the field. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, illustration was experiencing a golden age, fueled by the proliferation of illustrated magazines and books.

She began contributing to popular periodicals such as Once a Week, The Illustrated London News, and notably, The Graphic. Launched in 1869, The Graphic was renowned for its high-quality wood engravings and its focus on social realism alongside news reporting. Helen became one of its key early contributors and was highly regarded for the quality and sensitivity of her work, holding a prominent place among its staff artists. This work provided invaluable professional experience and public exposure. Fellow illustrators working for such publications included notable artists like Luke Fildes and Hubert von Herkomer, who also balanced illustration with painting careers.

Her talents extended to book illustration. One of her most celebrated commissions came in 1874 when she provided illustrations for the serialisation of Thomas Hardy's novel Far from the Madding Crowd in Cornhill Magazine. Her evocative drawings captured the pastoral atmosphere and emotional nuances of Hardy's Wessex, earning praise from the author himself. She also illustrated numerous children's books, including Juliana Horatia Ewing's popular Six to Sixteen: A Story for Girls and A Flat Iron for a Farthing. This early success demonstrated her versatility and her ability to connect visually with narrative content.

Marriage and the Turn to Watercolour

A significant turning point in both her personal and professional life occurred on August 22, 1874, when Helen Paterson married William Allingham. He was a well-regarded Irish poet and the editor of Fraser's Magazine, considerably older than her but deeply embedded in the literary and artistic circles of the time. Their circle of friends and acquaintances included luminaries such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Robert Browning, Thomas Carlyle, and John Ruskin, providing a stimulating intellectual environment.

Following her marriage, Helen Allingham made a conscious decision to move away from the demands of commercial illustration and dedicate herself primarily to watercolour painting. While illustration had provided income and recognition, watercolour offered greater artistic freedom and aligned more closely with her passion for capturing the nuances of light, colour, and atmosphere in the natural world. Her husband was supportive of her artistic ambitions. This shift marked the beginning of the phase for which she is most renowned today.

The Watercolourist: Style, Subject, and Technique

Helen Allingham's watercolours are characterized by their delicate execution, meticulous attention to detail, and profoundly nostalgic vision of rural England. She became particularly associated with the depiction of traditional thatched cottages, often nestled within abundant, colourful gardens or set against gentle, rolling landscapes. Her favoured locations included the counties of Surrey and Kent, and later the Isle of Wight, areas known for their picturesque villages and surviving vernacular architecture.

Her style was distinct. While influenced by Walker's rustic realism, Allingham's work generally presented a more idealized and romanticized view of country life. Figures often appear, sometimes children playing or women engaged in domestic tasks, but they are typically integrated harmoniously into the scene, contributing to the overall sense of peace and timelessness rather than depicting the harsh realities of agricultural labour. Her focus was on the beauty and perceived tranquility of the rural scene, offering an escape from the increasing industrialization and urbanization of Victorian Britain.

Technically, she worked with remarkable precision. Her watercolours often display fine brushwork, capturing the textures of stone, thatch, timber, and foliage with great accuracy. She had a keen eye for the effects of light, rendering dappled sunlight on cottage walls or the soft glow of an English summer afternoon. Interestingly, sources suggest she often worked with a relatively limited palette, favouring warm earth tones and subtle greens, blues, and the characteristic yellows noted by observers, which contributed to the harmonious and gentle quality of her work. Although trained in academic methods, she embraced the practice of sketching and painting outdoors (en plein air) whenever possible, lending her work a freshness and immediacy.

Life in Witley and the Influence of Birket Foster

In 1881, the Allinghams moved from London to Sandhills, near Witley in Surrey. This move proved immensely fruitful for Helen's art. The Surrey landscape, with its charming villages, wooded lanes, and traditional cottages, provided endless inspiration and became the backdrop for many of her most famous works. She immersed herself in documenting the local vernacular architecture, often seeking out cottages that retained their historic character.

Witley was already home to a vibrant community of artists. Notably, Myles Birket Foster, another highly successful watercolourist celebrated for his detailed and sentimental depictions of rural life and childhood, lived nearby. Foster's work, immensely popular with the public, shared certain affinities with Allingham's in its focus on picturesque rural subjects and meticulous technique, though Foster often included more anecdotal detail. Allingham undoubtedly knew Foster and moved within this artistic milieu, which likely provided both inspiration and collegial support. Her friendship with Kate Greenaway, another celebrated artist and illustrator known for her charming depictions of children in Regency-inspired dress, also flourished during this period. They were close friends, often sketching together and exhibiting their work in similar circles.

Professional Recognition and Exhibitions

Helen Allingham's shift to watercolour quickly brought critical acclaim and professional success. She began exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibitions and other prestigious venues like the Dudley Gallery. Her charming and skillfully executed paintings found a ready market among the Victorian public, who were drawn to her nostalgic portrayal of the English countryside.

A major milestone in her career came in 1890 when she was elected a full member of the Royal Watercolour Society (RWS), founded in 1804. Significantly, she was the first woman ever to be admitted to full membership, breaking a long-standing barrier and marking a crucial step forward for female artists seeking professional recognition within the established art institutions. This honour underscored the high regard in which her work was held by her peers. She remained an active and frequent exhibitor at the RWS for the rest of her life.

Her popularity led to several successful solo exhibitions. In 1886, the Fine Art Society in London hosted a major show titled 'Surrey Cottages', featuring sixty-six watercolours. This was followed by another successful exhibition, 'In the Country', the following year. These shows cemented her reputation as the pre-eminent painter of the English cottage and garden. She would go on to have several more solo exhibitions throughout her career, demonstrating her consistent output and enduring appeal. Her work was also reproduced in popular illustrated books, such as Happy England (1903), with text by Marcus B. Huish, which further broadened her reach.

Themes of Nostalgia and Conservation

Beyond their aesthetic appeal, Helen Allingham's watercolours carry a deeper resonance as documents of social and architectural history. She painted during a period of rapid change in Britain. The agrarian way of life was declining, industrialization was transforming landscapes and communities, and traditional building methods were giving way to standardized materials and designs.

Allingham felt a strong connection to the older, seemingly timeless, rural England that she depicted. There is an undeniable element of nostalgia in her work, a longing for a simpler, more picturesque past, which struck a chord with Victorian audiences experiencing the upheavals of modernity. However, her interest went beyond mere sentimentality. She possessed a genuine appreciation for the craftsmanship and beauty of the old cottages and farmhouses she painted, many of which were already falling into disrepair or being demolished.

Her meticulous renderings of these structures provide valuable architectural records. She captured details of timber framing, thatched roofs, local stonework, and cottage gardens with an accuracy born of close observation. In this sense, her work serves as a form of preservation, documenting buildings and landscapes that might otherwise have been lost to memory. Architects and historians have indeed consulted her paintings for insights into traditional building practices. Her art implicitly advocates for the value of this heritage, reflecting a burgeoning conservationist spirit.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

William Allingham passed away in 1889. Helen, now a widow with young children (Gerald Carlyle and Eva Margaret), continued to live in Surrey and support her family through her art. She remained remarkably productive, painting and exhibiting well into the twentieth century. In 1905, she collaborated with her brother, Arthur Paterson, on the book The Homes of Tennyson, providing twenty evocative watercolours of places associated with the Poet Laureate, a family friend.

Helen Allingham died on September 28, 1926, in Haslemere, Surrey, aged 78. She left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be admired for its technical skill, gentle beauty, and evocative portrayal of the English countryside.

Her legacy is significant. As an artist, she excelled in the demanding medium of watercolour, achieving a level of detail and atmospheric effect that few could match. As a professional woman in the Victorian era, she carved out a highly successful career, overcoming societal barriers to gain recognition from prestigious institutions like the RWS. Her friendship and interactions with contemporaries like Kate Greenaway, Myles Birket Foster, and the literary giants associated with her husband place her firmly within the cultural landscape of her time, alongside other prominent figures such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (connected via the Pre-Raphaelites and Ruskin) and George Eliot (representing the era's literary focus on realism and social change).

Most enduringly, Helen Allingham created an iconic vision of rural England. Her paintings of sun-drenched cottages, blooming gardens, and peaceful lanes have shaped popular perceptions of the English countryside for generations. While sometimes criticized for presenting an overly idealized view, her work undeniably captures a genuine affection for her subject matter and serves as a precious visual record of a bygone era. Her watercolours remain highly sought after by collectors and continue to be celebrated in exhibitions, ensuring that her gentle, meticulous art, chronicling the vanishing beauty of the English landscape, endures.

Representative Works

While specific titles often focused on location (e.g., A Cottage at Chiddingfold, Surrey, The Old Post Office, Freshwater, Isle of Wight), some key representative works and published collections include:

Illustrations for Thomas Hardy's Far from the Madding Crowd (1874)

Surrey Cottages (Exhibition and theme, 1886)

In the Country (Exhibition, 1887)

Happy England (Book with Marcus B. Huish, 1903)

The Homes of Tennyson (Book with Arthur Paterson, 1905)

Numerous individual watercolours depicting cottages and scenes in Surrey, Kent, Sussex, and the Isle of Wight.