Hendrick Avercamp stands as one of the most distinctive and beloved painters of the Dutch Golden Age. Born during a period of extraordinary artistic flourishing in the Netherlands, Avercamp carved a unique niche for himself, becoming the foremost specialist in the depiction of winter landscapes. His vibrant, detailed scenes of Dutch life unfolding on frozen canals and rivers capture a specific moment in time – the era often referred to as the Little Ice Age – with unparalleled charm and observational acuity. Known affectionately, and perhaps poignantly, as "de Stomme van Kampen" (The Mute of Kampen) due to being deaf and mute, Avercamp's art speaks volumes, offering a window into the joys, hardships, and everyday activities of 17th-century Holland during its coldest season.

Early Life and Training in a Golden Age

Hendrick Avercamp was born in Amsterdam in January 1585, baptized on the 27th of that month in the Oude Kerk (Old Church). His family, however, did not remain in the bustling metropolis for long. The following year, they relocated to the smaller, picturesque town of Kampen, situated on the Zuiderzee. This move would prove definitive, as Kampen became Avercamp's lifelong home and the backdrop, both literally and figuratively, for much of his artistic output.

His family background provided a foundation of learning and respectability. His father, Barent Avercamp, was initially an apothecary but later pursued studies to become a physician. His mother, Beatrix Petersdr Vekemans, hailed from a family with scholarly connections and capably managed the family apothecary shop after her husband changed professions. This environment likely fostered intellectual curiosity in the young Hendrick, even amidst the challenges posed by his condition. It is documented that Hendrick was deaf and likely mute from a very young age, a condition that profoundly shaped his life experiences.

Despite his inability to hear or speak, Avercamp's talent for drawing and painting must have been evident early on. Around the age of 18, likely by 1603 or shortly thereafter, he was sent back to Amsterdam to receive formal artistic training. There, he entered the studio of Pieter Isaacks. Isaacks, born in Helsingør, Denmark, but active in Amsterdam, was primarily known as a portrait and history painter. Studying under Isaacks would have provided Avercamp with a solid grounding in technique, composition, and the use of materials, even if their preferred subject matter ultimately diverged.

Amsterdam at the turn of the 17th century was a vibrant artistic hub. While training with Isaacks, Avercamp was inevitably exposed to the work of other influential artists active in the city. Crucially, he encountered the legacy and ongoing influence of Flemish landscape painters who had sought refuge in the Northern Netherlands. Artists like Gillis van Coninxloo III and David Vinckboons, both immigrants from the Southern Netherlands, were pioneers in developing a more naturalistic approach to landscape painting, moving away from purely imaginary scenes towards depictions rooted in observation, albeit often still stylized. Their work, particularly their detailed woodland scenes and lively figure groups, left a discernible mark on Avercamp's developing style. The influence of earlier Flemish masters, most notably Pieter Bruegel the Elder, whose own winter scenes were groundbreaking, also permeated the artistic atmosphere and undoubtedly shaped Avercamp's vision. Another potential influence from this period could be Hans Bol, known for his detailed small-scale landscapes and genre scenes.

The "Mute of Kampen": Life and Circumstances

After completing his training, likely around 1607 or 1608, Avercamp returned to Kampen. He would reside and work in this provincial town for the remainder of his life, establishing himself as its most famous artistic son. His deafness and mutism were defining characteristics, leading to the nickname "de Stomme van Kampen." While perhaps intended matter-of-factly at the time, modern perspectives recognize the potential for such labels to overshadow an individual's accomplishments.

Historical records offer glimpses into the reality of his condition and its perception. His mother, Beatrix, in her will dated 1633, referred to him with concern as her "mute and miserable son" ("stomme en miserable soone"). She took practical steps to ensure his future welfare, stipulating that he should receive an extra annual allowance of 100 guilders from a family trust fund, presumably recognizing that his condition might present financial challenges or limit his ability to manage affairs independently. In 17th-century Dutch society, individuals who were deaf and mute could face legal limitations regarding inheritance and property ownership, making such provisions by his mother particularly significant.

In that same year, 1633, Beatrix also submitted a petition to the Kampen municipal council requesting an annuity (lijftocht) for Hendrick. This suggests that despite his growing reputation as a painter, his financial situation may not have been entirely secure, or perhaps his mother simply sought to guarantee his stability after her death. Avercamp himself never married and appears to have lived a relatively quiet life centered around his art. His inability to hear or speak may have heightened his sense of visual observation, allowing him to capture the nuances of human interaction and the subtleties of the winter landscape with exceptional clarity. He passed away in Kampen and was buried in the Sint Nicolaaskerk (St. Nicholas Church) on May 15, 1634.

Artistic Style: From Flemish Roots to Dutch Realism

Hendrick Avercamp is celebrated as the first Dutch artist to specialize almost exclusively in painting winter landscapes. While not the absolute inventor of the theme – Pieter Bruegel the Elder had created iconic winter scenes decades earlier – Avercamp dedicated his career to exploring its possibilities, developing a distinct and highly influential style. His work forms a crucial bridge between the earlier Flemish landscape tradition and the burgeoning realism of the Dutch Golden Age.

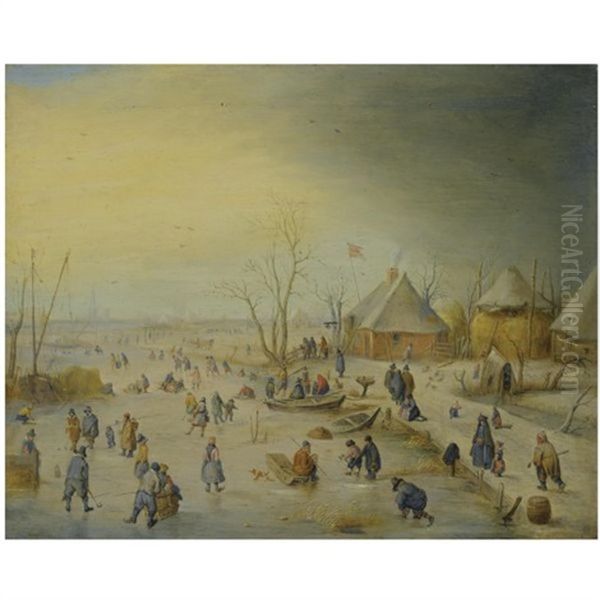

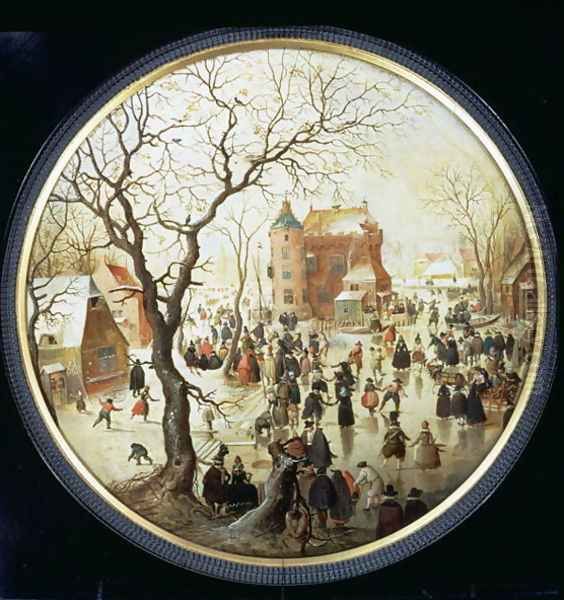

His early paintings clearly show the influence of his Flemish predecessors. They often feature a high viewpoint, offering a panoramic, almost map-like overview of the scene. The horizon line is placed high in the composition, allowing for a vast expanse of landscape filled with numerous small figures engaged in various activities. This approach, reminiscent of Bruegel, creates a bustling, encyclopedic quality, inviting the viewer to explore the myriad details scattered across the frozen surface. The colour palette in these early works can be bright and varied, with attention paid to the colourful costumes of the figures.

Over time, Avercamp's style evolved. While retaining the lively depiction of crowds and the focus on winter activities, his compositions gradually became more atmospheric and naturalistic. The viewpoint sometimes lowered, creating a more intimate connection with the scene. He developed a remarkable ability to render the specific light and atmosphere of a cold winter's day – the pale, diffuse sunlight, the crisp air, the subtle tones of snow and ice. His rendering of trees, stark and skeletal against the winter sky, and the architecture of nearby towns became increasingly sophisticated.

Avercamp worked primarily on panel, often in small or medium formats, although he also produced larger works. He was a master of oil paint but was also highly proficient in drawing, using pen and watercolour washes. Many of his drawings, often heightened with watercolour, were finished works in their own right, eagerly collected by contemporaries. These drawings reveal his keen eye for detail and his method of capturing figures and motifs from life, which he could then incorporate into his painted compositions. His technique involved fine brushwork, allowing for the precise delineation of figures, costumes, and landscape elements, contributing to the jewel-like quality of his best works.

Masterpieces of Ice and Snow

Avercamp's body of work is remarkably consistent in its theme, yet rich in variation and detail. His most famous paintings are often generically titled Winter Landscape or Scene on the Ice, followed by descriptive elements. Among his most celebrated works is Winter Landscape with Skaters, housed in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. This painting, likely created around 1608, exemplifies his early style. It presents a high viewpoint overlooking a frozen waterway bustling with activity near a town. Scores of figures populate the ice: elegant couples skate gracefully, common folk push sleds, children play games resembling ice hockey (kolf), and vendors ply their trades. The painting is a microcosm of Dutch society at leisure, rendered with vibrant colours and meticulous detail.

Another key work, A Scene on the Ice near a Town, dating from around 1615 and now in the National Gallery, London, shows a similar panoramic view but perhaps with a slightly greater sense of atmospheric unity. Again, the ice is teeming with life. Avercamp includes charming, sometimes humorous, anecdotal details: a couple embracing, a person who has fallen through the ice being rescued, dogs scavenging, and boats frozen solid near the shore. These vignettes add narrative interest and realism to the overall scene.

Avercamp often included specific identifiable landmarks from Kampen or its surroundings, grounding his scenes in a recognizable reality for his local audience, while their universal depiction of winter fun appealed to a broader market. His paintings frequently feature motifs like tents set up on the ice, horse-drawn sleighs, ice fishermen, and skaters of all skill levels, from the proficient to the comically clumsy.

He did not shy away from the harsher realities of winter either. Occasionally, his paintings include details like beggars seeking alms or, more graphically, animals that have perished in the cold. One well-known motif, appearing in several works, is a dead horse lying on the ice, sometimes being pecked at by crows or sniffed by dogs. These elements serve as reminders of the difficulties posed by severe winters, adding a layer of unsentimental observation beneath the overall cheerfulness of the scenes. Avercamp's ability to balance the picturesque with the prosaic is a hallmark of his unique vision.

Avercamp's World: Depicting Dutch Society

Avercamp's winter landscapes are more than just picturesque views; they are invaluable social documents of the Dutch Golden Age, particularly during the period known as the Little Ice Age (roughly 14th to 19th centuries), which saw significantly colder winters in Europe. The frozen canals and rivers became temporary extensions of the public sphere, transforming into communal spaces where people from all walks of life could mingle.

His paintings vividly capture this social mixing. Wealthy burghers in fine attire skate alongside simple peasants. Men engage in games like kolf, a precursor to both golf and ice hockey, played with a stick and ball on the ice. Women, bundled in warm clothing, glide on skates or ride in elegant horse-drawn sleighs. Children are everywhere, sliding, spinning tops, or simply enjoying the novelty of the frozen world. Commerce continues even on the ice, with vendors selling food and drink from stalls or tents.

These scenes reflect a society adapting to and even embracing the challenges of its climate. The ability to skate provided essential transportation when waterways froze, but it clearly also became a major form of recreation. Avercamp's detailed observation extends to the clothing, equipment (various types of skates and sleds), and social interactions of the figures. He captures gestures, postures, and groupings that convey a sense of lively, unposed reality. The collective enjoyment depicted in his works speaks to a strong sense of community and resilience.

By focusing on these everyday activities, Avercamp contributed significantly to the development of genre painting in the Netherlands. His work celebrated the ordinary lives of Dutch citizens, a theme that became central to Dutch art in the 17th century. His paintings offered his contemporaries a reflection of their own world, imbued with charm, detail, and a distinctly Dutch character.

Influence and Legacy

Hendrick Avercamp was highly successful during his lifetime. His paintings and drawings were popular and widely collected. His specialization in winter landscapes established him as the undisputed master of the genre in the early Dutch Golden Age, and his work had a significant impact on subsequent generations of artists.

He directly influenced a number of painters who also specialized in winter scenes, effectively creating a "school" of followers. Among the most notable were his own nephew, Barent Avercamp (1612-1679), who worked in a style very similar to his uncle's, though perhaps lacking the same level of finesse. Other artists who clearly followed Avercamp's lead in depicting lively ice scenes include Adam van Breen and Anthonie Verstraelen. Their works often emulate Avercamp's compositions, figure types, and focus on anecdotal detail.

More broadly, Avercamp's pioneering work helped to establish landscape painting as a major independent genre in the Dutch Republic. His influence can be seen in the work of slightly later landscape painters who, while developing their own styles, built upon the foundations he laid. Esaias van de Velde, for instance, created winter scenes that, while often simpler in composition, share Avercamp's interest in atmospheric effects and everyday life. Jan van Goyen, a leading figure in the "tonal" phase of Dutch landscape painting, also painted winter scenes that owe a debt to Avercamp's earlier models, though van Goyen emphasized mood and atmosphere over detailed description.

Even later masters of Dutch landscape, such as Aert van der Neer, known for his moonlight and winter scenes, and arguably even Jacob van Ruisdael, with his powerful and evocative landscapes, operated within a tradition that Avercamp helped to shape. Avercamp demonstrated that the native Dutch landscape, even in its harshest season, was a worthy subject for serious art, paving the way for the remarkable flourishing of landscape painting throughout the 17th century.

Today, Avercamp's works are held in major museums around the world, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Mauritshuis in The Hague, the National Gallery in London, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and many others. His paintings remain immensely popular for their charm, intricate detail, and evocative portrayal of a bygone era.

Historical Reputation and Reassessment

Hendrick Avercamp's reputation has remained consistently high, particularly as the quintessential painter of Dutch winter pleasures. Early accounts recognized his skill and the appeal of his chosen subject matter. His nickname, "de Stomme van Kampen," while highlighting his physical condition, also served to make him a memorable figure.

Over time, art historical assessment has deepened the understanding of his contribution. Initially appreciated primarily for the anecdotal charm and documentary value of his scenes, scholars later emphasized his crucial role in the development of Dutch landscape painting. His ability to synthesize the detailed narrative style inherited from Flemish tradition (especially from Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Gillis van Coninxloo, and David Vinckboons) with an emerging Dutch sensibility for realism and atmospheric observation is now widely recognized. He is seen not just as a specialist painter but as an innovator who helped define a national school of landscape art.

Modern scholarship has also sought to move beyond the potentially limiting perception associated with his deafness. Rather than viewing it as a deficit, some interpretations consider how his unique sensory experience might have informed his intensely visual focus and his ability to capture the subtleties of gesture and interaction without relying on sound. The re-evaluation encourages viewing his work through the lens of his artistic strengths and achievements, rather than primarily through the prism of his disability. His mother's documented concerns about his welfare provide poignant context but do not diminish the evidence of his successful career and lasting artistic impact.

Avercamp's enduring appeal lies in his ability to transport viewers to the frozen canals of 17th-century Holland, offering a vision that is both historically specific and universally relatable in its depiction of community, resilience, and the simple joys found even in the depths of winter.

Conclusion

Hendrick Avercamp occupies a unique and cherished place in the history of Dutch art. As the premier specialist in winter landscapes during the early Golden Age, he captured the essence of Dutch life during the Little Ice Age with unparalleled vibrancy and detail. Working from his lifelong home in Kampen, the "Mute of Kampen" developed a distinctive style that blended the narrative richness of Flemish tradition with the burgeoning realism and atmospheric sensitivity of Dutch painting. His bustling ice scenes, filled with skaters, sleighs, and townsfolk from all walks of life, are not only charming depictions of winter recreation but also valuable social documents and masterful examples of early landscape art. Through his dedicated focus and keen observational skills, Avercamp influenced subsequent generations of artists and secured his legacy as a foundational figure in the great tradition of Dutch landscape painting. His work continues to delight viewers with its intricate detail, lively spirit, and evocative portrayal of winter in the Netherlands centuries ago.