An Introduction to a Master of Animal Portraiture

Henriette Ronner-Knip stands as a significant figure in 19th-century European art, a Dutch-Belgian painter whose name became virtually synonymous with charming and lifelike depictions of cats. Born into an artistic dynasty, she navigated the challenges faced by female artists of her time to achieve international renown. Her career spanned a period of significant artistic change, rooted in Romanticism but demonstrating a keen observational skill that bordered on Realism. While celebrated for her intimate portrayals of domestic felines, her oeuvre also encompassed dogs, other animals, and earlier works in landscape and still life. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of an artist who captured the essence of animal life with remarkable sensitivity and technical prowess.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in the Netherlands

Henriette Knip was born in Amsterdam on May 31, 1821. Artistry was deeply ingrained in her family heritage. Her father, Josephus Augustus Knip (1777-1847), was a respected neoclassical landscape and animal painter who provided Henriette with her primary and, indeed, only formal art education. He had studied in Paris and Rome, bringing a breadth of experience to his teaching. Henriette's mother, Pauline Rifer de Courcelles, was herself a painter specializing in birds, though some historical accounts suggest Henriette's biological mother may have been Cornelia van Leeuwen, who was reportedly her father's mistress at the time of his marriage to Pauline. This element adds a layer of complexity to her early family life narrative.

Regardless of the specifics of her parentage, the artistic environment was formative. Henriette showed prodigious talent from a young age. Her father guided her development rigorously, recognizing her potential. Tragedy struck early when her father began suffering from vision problems, eventually going blind in one eye. By her teenage years, Henriette was already contributing significantly to the family's income through her art, taking on the role of the breadwinner. She achieved her first commercial success at the tender age of fifteen, selling a painting. Her formal debut into the art world occurred around 1835, with exhibitions following, including a notable showing at the "Exhibition of Living Masters" in The Hague in 1838. This marked her arrival on the Dutch art scene.

Her early works reflected her father's influence, encompassing landscapes and genre scenes, often featuring animals but not yet with the focused intensity that would later define her career. She also painted still lifes and farm scenes. An early significant work from this period is titled "The Death of a Friend," demonstrating her ability to convey emotion even before specializing in animal portraiture. Her brother, August Knip (1819-c.1861), also pursued an artistic career, further cementing the family's connection to the Dutch art world, which included prominent figures like the landscape painter Barend Cornelis Koekkoek.

A New Chapter: Brussels, Marriage, and Shifting Focus

In 1850, Henriette Knip married Feico Ronner (1819-1883). This union marked a significant turning point in her life and career. The couple moved to Brussels, the vibrant capital of newly independent Belgium, which boasted a thriving art scene. Feico Ronner was also an artist, but he suffered from chronic poor health, which often prevented him from working consistently. Consequently, the financial responsibility for the household largely fell upon Henriette. She managed their affairs adeptly, allowing Feico to paint when his health permitted, while she pursued her own burgeoning career with determination.

The move to Brussels exposed Ronner-Knip to new artistic currents and a different clientele. Belgium, like the Netherlands, had a strong tradition of Realism and genre painting. Artists like Alfred Stevens and Jan Verhas were prominent figures in the Brussels scene, capturing scenes of contemporary life. While Ronner-Knip's style remained rooted in her Dutch training, the environment likely encouraged her meticulous attention to detail and perhaps influenced the settings of her later works. Brussels would remain her home for the rest of her long life.

It was during her time in Brussels, particularly after 1870, that Henriette Ronner-Knip began to specialize increasingly in the subject that would bring her lasting fame: the domestic cat. While she had always included animals in her work and had painted dogs with considerable skill – works like "Hounds Hunting in a Field" attest to this – the shift towards cats became defining. This focus coincided with a growing appreciation for cats as household pets among the European bourgeoisie, providing a ready market for her charming and relatable depictions.

The Reign of the Cat: Signature Style and Popular Acclaim

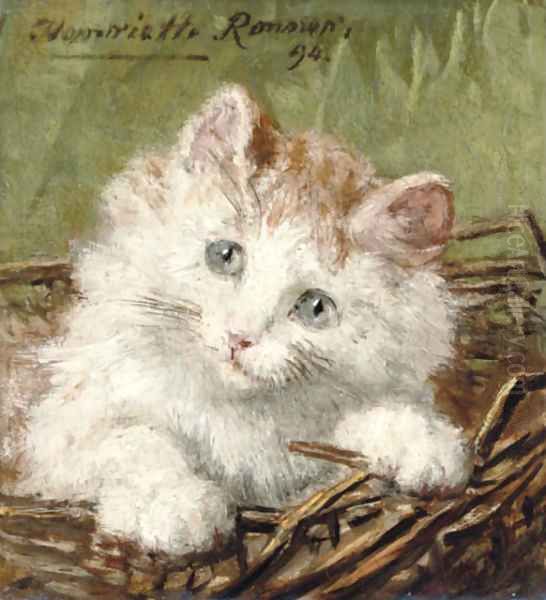

Henriette Ronner-Knip's cat paintings became immensely popular across Europe, particularly in Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Belgium. Her success stemmed from a combination of technical skill, keen observation, and an ability to tap into the sentimental affections of her audience. She often depicted cats, especially playful kittens, in comfortable, middle-class or even opulent interior settings – lounging on silk cushions, tumbling out of baskets, interacting with luxurious props like fans, pearls, or musical instruments.

Titles such as "Mother Cat with Kittens Playing on a Footstool," "A Mother's Pride," "Cat and Bird," and "Cat and Fish" give a sense of her typical subjects. She excelled at capturing the textures of fur, the gleam in a cat's eye, and the characteristic postures and movements of her subjects – the stealthy crouch, the playful swat, the contented curl. There was often an element of anthropomorphism in her work; the cats displayed recognizable 'personalities' – mischievous, curious, maternal, regal. This resonated deeply with pet owners and admirers of feline grace and independence.

To achieve such lifelike results, Ronner-Knip was a meticulous observer. Later in life, she reportedly kept numerous cats in her home studio, sometimes placing them in a glass-fronted case to study their poses and interactions without interruption. This dedication to direct observation allowed her to move beyond generic representation and capture the individual character of her subjects. Her ability to render the softness of fur and the play of light upon it was particularly admired.

Her popularity extended to the highest levels of society. Patrons included Queen Marie Henriette of Belgium and Emperor Wilhelm I of Germany (King of Prussia). Her works commanded high prices and were widely reproduced as prints, further cementing her fame and making her images accessible to a broader public. She became one of the most successful female artists of her era, achieving financial independence through her art – a significant accomplishment in the 19th century.

Artistic Style: Romantic Sensibility, Realistic Detail

Henriette Ronner-Knip's artistic style is best characterized as belonging to the later phase of Romanticism, infused with a strong element of Realism, particularly in her detailed rendering of animals and their environments. Unlike the dramatic historical or allegorical subjects often favored by earlier Romantics, her focus was intimate and domestic. However, her work retained a Romantic sensibility in its warmth, its focus on emotion (albeit animal emotion), and its often idealized portrayal of her subjects.

Her technique was characterized by fine, controlled brushwork. She built up textures meticulously, particularly the soft, varied fur of cats and dogs. Her palette was generally warm, employing rich browns, reds, and golds, often contrasted with cooler tones in fabrics or backgrounds, creating a sense of comfort and luxury. The "feathery" brushstrokes often noted in descriptions of her work refer to the delicate way she rendered fur, giving it a tactile quality.

While contemporary movements like Impressionism, championed by artists such as Édouard Manet (who occasionally depicted cats, albeit in a very different style) and Berthe Morisot, were exploring light and color in revolutionary ways, Ronner-Knip remained committed to a more traditional, detailed approach. Her realism was focused on accurate representation rather than capturing fleeting moments or atmospheric effects. This fidelity to appearance was key to her appeal. She provided a clear, tangible image of beloved animals, rendered with undeniable skill.

Compared to other prominent animal painters of the era, such as the British artist Sir Edwin Landseer, known for his dramatic and often anthropomorphic portrayals of dogs and stags, or the French painter Rosa Bonheur, celebrated for her large-scale, powerful depictions of farm animals and lions, Ronner-Knip carved a distinct niche. Her focus was smaller in scale, more domestic, and arguably more psychologically intimate, particularly in her studies of cats. She shared with them, however, a deep understanding of animal anatomy and behavior, elevating animal painting beyond mere illustration.

Professional Recognition, Memberships, and Awards

Henriette Ronner-Knip's talent and dedication earned her significant recognition within the formal art institutions of her time. In an era when opportunities for female artists were often limited, she achieved notable milestones. She became the first woman admitted as an active member ("werkend lid") to the prestigious Arti et Amicitiae society in Amsterdam, a hub for Dutch artists. She was also an honorary member of the Rotterdam Academy of Fine Arts.

Her work was frequently included in major exhibitions across Europe, including salons in Brussels, Antwerp, Amsterdam, The Hague, Paris, and London. These exhibitions brought her critical attention and numerous accolades. She received medals at exhibitions in The Hague (1845), Amsterdam (1848, 1883), Paris (1855, 1878), and Antwerp (1894), among others.

Perhaps the most significant official honors bestowed upon her came from royalty. In 1887, she was inducted into the Belgian Order of Leopold, receiving the Knight's Cross, a prestigious honor presented by King Leopold II. Later, in 1901, she was awarded the Order of Orange-Nassau in her native Netherlands. These awards underscored her status as a leading artist in both her country of birth and her adopted homeland. Her success provided an inspiring example for other aspiring female artists.

Connections, Collaborations, and Artistic Lineage

Henriette Ronner-Knip's artistic life was interwoven with connections, both familial and professional. Her primary artistic lineage came directly from her father, Josephus Augustus Knip. She, in turn, passed on the artistic tradition to her own children. Three of her offspring – Alfred Ronner (1851-1901), Alice Ronner (1857-1957), and Emma Ronner (1860-1936) – became artists themselves. Alfred specialized in genre scenes and portraits, while Alice and Emma often painted still lifes, particularly flowers, sometimes exhibiting alongside their mother. This created a multi-generational artistic family active primarily in Brussels.

Beyond her immediate family, records indicate occasional collaborations. She is known to have sometimes worked with the Belgian genre painter and sculptor David Col (1822-1900), though the exact nature and extent of these collaborations are not always clearly documented. Her husband, Feico Ronner, remained an artistic presence in her life, even if his output was limited by illness.

Her participation in exhibitions naturally placed her work alongside that of numerous contemporaries. In the Netherlands, she would have exhibited alongside artists associated with the Hague School, such as Anton Mauve and Jozef Israëls, though their focus on landscape and peasant life differed greatly from her own. The earlier Dutch artist Johan Barthold Jongkind, a forerunner of Impressionism, was also active during her formative years. In Belgium, her contemporaries included not only genre painters like Stevens and Verhas but also landscape artists and portraitists who defined the Belgian art scene of the latter 19th century.

While direct collaborative ties beyond Col and her family seem limited based on current knowledge, her immense popularity meant her work was widely known and discussed within artistic circles. She operated within a rich network of exhibitions, dealers, patrons, and fellow artists, even if her primary focus remained her own studio practice.

Placing Ronner-Knip in Context: 19th-Century Animal Painting

The 19th century witnessed a significant rise in the popularity and status of animal painting (animalier art). This was fueled by several factors: the ongoing influence of Romanticism with its emphasis on nature and emotion, advancements in zoological studies, the growth of the middle class with increased pet ownership, and a burgeoning market for art that depicted familiar and beloved subjects. Henriette Ronner-Knip emerged as a leading figure within this specific genre.

Her work can be seen as part of a broader European trend. In Britain, Sir Edwin Landseer achieved enormous fame with his often sentimentalized depictions of animals, particularly dogs, reflecting Victorian values. In France, Rosa Bonheur gained international acclaim for her realistic and unsentimental portrayal of animals, working on a scale and with a technical mastery that rivaled male history painters. Artists like Constant Troyon of the Barbizon School also made significant contributions to animal painting within landscape contexts.

Ronner-Knip's contribution was unique in its sustained and intimate focus on domestic cats, rendered with a combination of Dutch precision and Romantic warmth. While some critics, particularly later adherents of Modernism, might have dismissed her work as overly sentimental or commercially driven, it undeniably met a significant public demand and demonstrated exceptional technical skill within its chosen parameters. She elevated the depiction of the common house cat to a level of fine art that resonated deeply with her contemporaries. Her success also highlighted the increasing visibility and professionalization of female artists during the period, alongside figures like Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, although their styles and artistic circles differed significantly.

Later Life, Legacy, and Historical Assessment

Henriette Ronner-Knip remained active as an artist well into her old age. She continued to live and work in Brussels, residing in a comfortable house with a large garden. This environment allowed her to keep the animals that served as her models readily available – reports mention not only numerous cats but also hunting dogs and even a parrot. Her dedication to her craft remained unwavering. In her later years, she even experimented with creating paper sculptures of her animal subjects, showcasing a continued creative drive.

She passed away in Ixelles, Brussels, on March 2, 1909, at the age of 87, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a formidable reputation. Her paintings had already found their way into numerous private and public collections during her lifetime. Today, her works are held by major museums including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, and internationally in institutions like the National Gallery, London.

Historically, Ronner-Knip's reputation experienced fluctuations typical for artists whose work falls outside the main narrative of avant-garde Modernism. During her lifetime and in the decades immediately following her death, she was celebrated for her technical skill and the undeniable charm of her subjects. However, with the rise of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and subsequent modernist movements, her detailed, Romantic-Realist style came to be seen by some critics as conservative or overly focused on popular appeal rather than artistic innovation. Terms like "sentimental" were sometimes applied dismissively.

In recent decades, however, there has been a renewed appreciation for her work. Art historians recognize her exceptional skill as an animal painter, her significant success as a female artist in a male-dominated field, and the value of her work as a reflection of 19th-century cultural tastes and the growing human-animal bond. Her paintings continue to be popular at auction and remain beloved by the public for their warmth, detail, and affectionate portrayal of feline life. Henriette Ronner-Knip secured a lasting place in art history as the preeminent painter of cats of her generation.