Henry Charles Fox stands as a significant figure in British art during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born in London in 1860, his life and career spanned a period of considerable social and industrial change in Britain, themes that would subtly permeate his artistic output. Fox passed away in 1925, leaving behind a substantial body of work primarily focused on capturing the landscapes and daily life of the English countryside. He was particularly renowned for his skill as a watercolourist, though he also worked in oils and produced etchings. His art offers a window into a world undergoing transformation, often imbued with a sense of pastoral calm yet acknowledging the realities of rural existence.

Fox's dedication to his craft saw him become a regular exhibitor at prestigious institutions, solidifying his reputation among collectors and the art-viewing public. His work resonates with an appreciation for the natural world and the human element within it, characteristics that defined much of the popular landscape art of his era. Understanding Fox requires looking not only at his individual achievements but also at the broader artistic context in which he operated.

Early Career and Artistic Formation

Henry Charles Fox embarked on his professional artistic journey around 1880. This significant year marked his debut at the esteemed Royal Academy of Arts in London, the premier exhibition venue in Britain at the time. Having a work accepted by the Royal Academy was a crucial step for any aspiring artist, signalling a level of competence and professional recognition. Fox would continue to exhibit there consistently for over three decades, showcasing a total of twenty paintings under its roof by 1913. This long association indicates a sustained level of quality and acceptance by the Academy's selection committees.

While specific details about his formal training remain somewhat scarce in readily available records, his technical proficiency, particularly in watercolour, suggests a solid grounding in academic principles. The late Victorian era offered various avenues for artistic education, from formal Academy schools to private tutelage and self-directed study through sketching clubs and observation. Fox's development likely involved a combination of these elements. His early works already displayed the keen observational skills and sensitivity to atmosphere that would characterize his mature style.

The source material mentions potential influences like Eldon Grier, Armstrong William, and Goodrich Roberts. While Grier and William are less prominent names in the mainstream narrative of British art history of this exact period (requiring careful verification), the mention of Goodrich Roberts potentially points towards an appreciation for strong composition and perhaps a certain approach to colour relationships, if this influence is accurate. However, Fox's primary tutors remain the landscapes themselves and the established traditions of British watercolour painting passed down from artists like J.M.W. Turner and David Cox, albeit adapted to late Victorian sensibilities.

His choice of subject matter – the English countryside – was established early on. This was a popular genre, appealing to a growing urban population who often romanticized rural life. Fox distinguished himself through his consistent focus and the specific way he rendered these familiar scenes, balancing topographical accuracy with atmospheric effect. The publication of his etchings by Gladwell Brothers, noted as occurring in the 1880s, further indicates his growing commercial viability and reach beyond the exhibition halls early in his career.

The Artistic Milieu: Late Victorian and Edwardian Britain

Henry Charles Fox worked during a dynamic period in British art. The towering influence of the Royal Academy remained, but its dominance was increasingly challenged by new artistic movements and alternative exhibition societies. Landscape painting, Fox's chosen field, held a cherished place in the British tradition, yet it too was evolving. The detailed, often moralizing landscapes of the mid-Victorians, influenced by John Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites, were giving way to different approaches.

One major force was the growing awareness of French Impressionism. While few British artists became outright Impressionists in the French mould, the movement's emphasis on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and atmosphere, and looser brushwork certainly influenced many. Artists like Philip Wilson Steer and Walter Sickert were more directly engaged with these French developments. Fox, while clearly aware of Impressionist techniques regarding light and colour, seems to have integrated them more subtly into a fundamentally naturalistic framework, rather than fully adopting the Impressionist ethos.

Simultaneously, there was a strong current of realism, particularly in depicting rural life. The artists of the Newlyn School in Cornwall, such as Stanhope Forbes and Walter Langley, focused on portraying the everyday lives and hardships of fishing and farming communities with unvarnished realism and often a sombre palette. Herbert Henry La Thangue also became known for his powerful, naturalistic depictions of agricultural labour, sometimes termed "rural naturalism." While Fox's work often featured figures engaged in rural activities, his overall tone tended to be less gritty and more pastoral than that of the core Newlyn painters or La Thangue.

Watercolour painting itself enjoyed immense popularity. Artists like Myles Birket Foster (though slightly earlier, his influence persisted) and Helen Allingham specialized in charming, often idealized depictions of cottages, gardens, and gentle countryside, catering to a strong market demand. Fox operated within this popular watercolour tradition but often brought a slightly broader landscape perspective and perhaps a less overtly sentimentalized view than someone like Allingham.

Animal painting also remained popular, with artists like Thomas Sidney Cooper renowned for his meticulous depictions of cattle and sheep in pastoral settings, and Heywood Hardy known for his sporting scenes and depictions of horses. Fox frequently included animals, particularly sheep and horses, as integral parts of his rural landscapes, demonstrating skill in their rendering. Established landscape painters like Benjamin Williams Leader and George Vicat Cole continued to produce popular, often large-scale, picturesque views that adhered more closely to traditional compositional formulas. Fox's work existed alongside these varied strands, carving its own niche.

Fox's Domain: The English Rural Scene

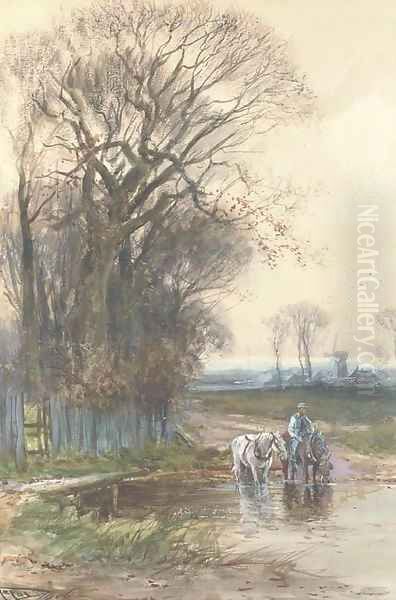

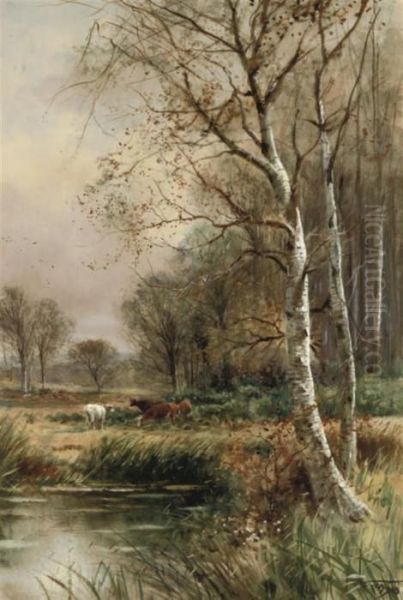

The heart of Henry Charles Fox's artistic output lies in his depiction of the English countryside, particularly the southern counties like Surrey and Sussex, known for their rolling hills, wooded lanes, and picturesque villages. His paintings transport the viewer to a world of agricultural rhythms, quiet lanes, and meandering rivers. He seemed particularly drawn to the daily activities that defined rural existence.

Common subjects include farmers working the land, perhaps guiding a horse-drawn plough or tending to livestock. Shepherds watching over their flocks are a recurring motif, allowing for studies of animal behaviour and the integration of figures into the wider landscape. Harvest scenes, capturing the golden light and communal effort of late summer, appear frequently. Country roads, often muddy tracks winding through fields or woods, serve as compositional devices leading the viewer's eye into the scene, sometimes populated by a lone figure, a horse and cart, or animals.

Fox paid close attention to the changing seasons, rendering the fresh greens of spring, the lush foliage of summer, the rich colours of autumn, and the stark beauty of winter landscapes, sometimes under snow. He was adept at capturing different times of day and weather conditions – the clear light of morning, the warm glow of late afternoon, the diffused light of an overcast day, or the dramatic skies preceding or following rain. This sensitivity to atmospheric conditions is a key element of his style.

His work often includes architectural elements – thatched cottages, farm buildings, village churches, stone bridges – but usually as components of the broader landscape rather than the primary focus. They serve to anchor the scene and provide context for the human and animal activity depicted. Water, in the form of rivers, streams, or ponds, also features regularly, allowing Fox to explore reflections and the interplay of light on water surfaces.

While often peaceful and picturesque, his scenes are not necessarily idealized fantasies. They depict working landscapes and acknowledge the labour involved. The inclusion of figures going about their daily tasks grounds the scenes in reality. As noted in the initial information, Fox was interested in documenting the changing face of rural life, potentially capturing the transition from older farming methods and the subtle encroachment of modernity, although this aspect might be more nuanced than overtly stated in many of his works.

Mastery of Mediums: Watercolour, Oil, and Etching

Henry Charles Fox was primarily celebrated as a watercolourist. This medium, with its transparency and luminosity, was perfectly suited to capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere that were central to his artistic vision. He demonstrated a confident handling of washes, layering colours to build depth and tone without sacrificing freshness. His technique allowed for both broad atmospheric effects in skies and water, and finer detail in rendering trees, foliage, figures, and architecture.

His watercolour palette was typically naturalistic, reflecting the actual colours of the landscape, but employed with a sensitivity to colour harmony and the way light affects local colour. He understood how to use contrasting warm and cool tones to create effects of sunlight and shadow, and how to use reserved areas of white paper or scratching out highlights to represent sparkle and brilliance. The overall impression is one of skilled control combined with an expressive touch.

Although best known for watercolours, Fox also worked in oil paints. His oils often tackled similar subjects to his watercolours – rural landscapes, farming scenes, coastal views. Working in oil allowed for greater richness of colour, impasto effects (building up thick layers of paint), and the possibility of working on a larger scale. While perhaps less numerous than his watercolours, his oil paintings form an important part of his oeuvre, demonstrating his versatility across mediums.

Furthermore, Fox engaged with printmaking, specifically etching. The mention of Gladwell Brothers publishing his etchings in the 1880s highlights this aspect of his work. Etching, a process involving drawing through a wax ground on a metal plate and then using acid to bite lines into the plate, allowed artists to create multiple original prints. This made their work accessible to a wider audience beyond those who could afford unique paintings. Fox's etchings likely translated his popular landscape and rural subjects into a linear, tonal medium, retaining the atmospheric qualities of his paintings.

This multi-faceted approach – mastering watercolour, working competently in oil, and engaging with the print market through etching – marks Fox as a versatile and commercially aware artist of his time. He understood the different potentials of each medium and utilized them effectively to convey his artistic vision and reach his audience.

Style: A Blend of Tradition and Impression

Defining Henry Charles Fox's style requires acknowledging its roots in the British landscape tradition while recognizing his absorption of contemporary influences, notably a moderated form of Impressionism. He was not a radical innovator intent on overturning artistic conventions, but rather a skilled practitioner who adapted existing modes of representation to his own sensibilities.

His work is fundamentally representational and naturalistic. He observed the countryside closely and aimed to depict it faithfully, capturing the specific character of places, the structure of trees, the forms of animals, and the details of rural life. This aligns him with the long tradition of British landscape painting that valued topographical accuracy and detailed observation. Artists like Benjamin Williams Leader or Alfred de Bréanski Sr. represent a more purely traditional approach popular at the time, often focusing on grander, more composed views.

However, Fox's handling of light and atmosphere sets him apart from purely academic or topographical painters. He was clearly interested in the effects of light – how it falls across a field, filters through trees, or reflects off water. His brushwork, particularly in watercolours, could be relatively loose and suggestive, especially in skies and distant passages, aiming to capture a sense of immediacy and vibrancy. This sensitivity to transient conditions and the use of colour to depict light, rather than just form, shows an awareness of Impressionist principles.

Unlike the French Impressionists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, Fox did not typically dissolve form completely into light and colour, nor did he usually employ the broken brushwork or high-keyed palette consistently associated with the movement. His colour remained largely based on local observation, enhanced for atmospheric effect rather than radically altered according to colour theory. His compositions generally remained well-structured, often employing traditional landscape conventions.

Compared to the rural naturalism of Herbert Henry La Thangue or Stanhope Forbes, Fox's work is generally less focused on social commentary or the harsh realities of labour. While he depicted work, the overall mood is often more serene and picturesque. His style might be seen as sitting somewhere between the detailed charm of Helen Allingham and the more rugged realism of the Newlyn School, incorporating a greater emphasis on atmospheric light than the former, but less social weight than the latter. He found a balance that proved popular with the Edwardian public.

Themes: Recording a Changing Landscape

Beyond the purely visual appeal, the works of Henry Charles Fox often resonate with underlying themes relevant to his time. His consistent focus on the countryside can be interpreted, in part, as a response to the rapid industrialization and urbanization that had transformed Britain over the preceding century. For many city dwellers, the countryside represented an escape, a repository of traditional values, and a connection to a perceived simpler, more wholesome way of life. Fox's paintings catered to this sentiment, offering images of pastoral tranquility.

However, the provided information suggests he was also interested in depicting the changes occurring within the countryside itself, influenced by industrialization and conflict (likely referring to the period leading up to and including World War I). While his works might not overtly depict factories or modern machinery, the changes could be reflected more subtly – perhaps in the types of farm equipment shown, the presence or absence of figures suggesting shifts in population, or a general mood that hints at underlying tensions. His 1914 exhibition titled "Rural London – Sketches" specifically suggests an interest in the interface between the expanding city and the surrounding countryside.

His depictions of everyday rural labour – ploughing, harvesting, shepherding – can be seen as a documentation of traditional practices that were increasingly being mechanized. In this sense, his work, like that of many artists focusing on rural themes at the time, serves as a historical record, capturing aspects of life that were beginning to disappear. There is often a sense of quiet dignity afforded to the figures in his landscapes, acknowledging their connection to the land and their role in its cultivation.

The recurring motif of the journey, often represented by figures or carts on a road, like in his work "Return From Market" (1918), can be seen as symbolic of life's passages or the simple rhythms of daily travel within the rural community. These scenes often possess a gentle narrative quality, inviting the viewer to contemplate the story behind the image. Fox's art, therefore, operates on multiple levels: as aesthetically pleasing depictions of nature, as documents of rural life, and as reflections on a society undergoing significant transition.

Exhibition History and Recognition

Henry Charles Fox's career was significantly shaped by his active participation in the major art exhibitions of his day. As previously mentioned, his long association with the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) in London, from 1880 to 1913, was crucial. Exhibiting regularly at the RA Summer Exhibition placed his work before a large and influential audience, including potential patrons, critics, and fellow artists. The RA was the establishment venue, and consistent acceptance there conferred considerable prestige.

Beyond the RA, Fox sought wider exposure by submitting works to other important institutions across Britain. He exhibited at the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA), another significant London venue often seen as slightly more progressive or accessible than the RA at certain periods. His participation extended to the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours (RI), a natural fit given his proficiency in the medium, and the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) in Dublin, indicating a reach beyond England.

Furthermore, he exhibited with the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in Edinburgh, demonstrating his engagement with the art scene north of the border. The mention of him exhibiting scenes of Brighton at the London Photographic Society is intriguing; while primarily an art painter, this suggests either an interest in photography himself, or perhaps exhibiting watercolours alongside photographic works in themed exhibitions, reflecting the complex relationship between painting and the newer medium of photography, pioneered earlier by figures like William Henry Fox Talbot (though Talbot was primarily known for his photographic innovations, not painting).

His solo or themed exhibitions, such as the "Rural London – Sketches" show in 1914 mentioned in the source material, would have provided opportunities to present a cohesive body of work exploring a specific theme or region, further enhancing his reputation. Success in these various venues not only built his critical standing but also facilitated sales, allowing him to sustain a career as a professional artist. The regularity and breadth of his exhibition record underscore his position as a recognized and respected landscape painter within the British art world of his time.

Notable Works and Artistic Signature

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be needed for a definitive list, certain works and types of scenes are characteristic of Henry Charles Fox. The watercolour "Return From Market," dated 1918, is cited as a representative piece. This title suggests a typical Fox subject: a rural figure, likely a farmer, perhaps with a horse and cart, depicted on a country road at the end of the day. Such a scene would allow Fox to showcase his skill in rendering figures, animals (horses were a frequent and well-executed subject for him), landscape setting, and atmospheric effects, possibly the warm light of late afternoon or evening.

Many of his works carry titles that clearly indicate their subject matter and reflect his focus: "A Surrey Lane," "Harvest Time," "Ploughing Team," "Sheep Resting by a River," "Near Arundel," "A Sussex Farmstead." These titles point to his favoured locations in Southern England and his recurring themes of agricultural activity, pastoral scenes, and specific landscape features. His works often feature a strong sense of place, capturing the particular character of the English countryside.

Key elements of his artistic signature include:

1. Atmospheric Sensitivity: A consistent focus on capturing the quality of light and weather conditions, often lending a distinct mood to the scene – be it tranquil, bright, or brooding.

2. Competent Draughtsmanship: A clear ability to draw figures, animals (especially horses and sheep), and architectural elements accurately within the landscape context.

3. Balanced Compositions: His landscapes are typically well-structured, often using roads, rivers, or lines of trees to lead the viewer's eye into the distance, creating a sense of depth.

4. Harmonious Colour: While naturalistic, his colour palettes are carefully chosen for harmony and emotional effect, effectively conveying the season and time of day.

5. Integration of Figures/Animals: Unlike some landscape painters who focused purely on nature, Fox frequently included human figures and animals, making them integral parts of the working or pastoral landscape.

His works were popular during his lifetime and continue to be sought after by collectors of traditional British landscape painting. They appeal through their technical skill, their evocative portrayal of the countryside, and their nostalgic charm, representing a specific and well-loved genre within British art history.

Legacy and Conclusion

Henry Charles Fox occupies a solid and respected place within the history of British landscape painting from the late Victorian era through the early twentieth century. While not a revolutionary figure who dramatically altered the course of art, he was a highly skilled and prolific artist who excelled in capturing the nuances of the English countryside, particularly in the medium of watercolour. His work found favour with the public and secured him regular exhibition space at the nation's leading art institutions for over three decades.

He successfully navigated an art world in transition, absorbing subtle influences from Impressionism regarding light and atmosphere while remaining fundamentally rooted in the British naturalistic tradition. His chosen subject matter – the fields, lanes, farms, and rural inhabitants of England – resonated deeply with contemporary audiences, offering both aesthetic pleasure and a connection to a landscape and way of life that seemed increasingly under pressure from modernization.

His contemporaries included artists pursuing various paths: the academic grandeur of painters like Benjamin Williams Leader, the detailed charm of watercolourists like Helen Allingham, the gritty realism of the Newlyn School painters like Stanhope Forbes and Walter Langley, the rural naturalism of Herbert Henry La Thangue, and the more avant-garde explorations linked to French movements. Fox carved his own niche within this diverse scene, creating works characterized by atmospheric sensitivity, competent draughtsmanship, and a gentle, observant eye.

Today, his paintings serve as more than just pleasant depictions of scenery. They are valuable documents of rural England during a specific period, capturing agricultural practices, landscapes, and a certain mood that speaks of both continuity and change. For collectors and enthusiasts of British art, Henry Charles Fox remains an important representative of the enduring tradition of landscape painting, a chronicler of the fields and seasons, and a master of watercolour technique whose works continue to evoke the timeless appeal of the English countryside. His consistent output and exhibition success mark him as a significant professional artist of his generation.