Henry Inman stands as one of the most significant and versatile American artists of the first half of the 19th century. Active during a formative period in the nation's cultural development, Inman excelled not only as a portrait painter, capturing the likenesses of prominent figures and everyday citizens alike, but also distinguished himself in genre painting, landscape, and miniature work. His career, though tragically cut short, left an indelible mark on American art, reflecting the tastes and aspirations of a young republic. He was a founding member of the National Academy of Design and its first vice-president, playing a crucial role in shaping the professional landscape for artists in the United States.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born on October 28, 1801, in Utica, New York, Henry Inman was the son of English immigrants. His family's relocation to New York City in 1812 proved pivotal for his artistic development. The bustling metropolis, rapidly becoming the cultural and commercial heart of the young nation, offered opportunities and exposure that would have been unavailable in a smaller town. It was here that Inman's innate talent for drawing began to flourish, attracting notice at an early age.

The decision to pursue art professionally was made in 1814, when a fortuitous encounter set him on his path. At the tender age of thirteen, Inman visited the studio of John Wesley Jarvis, then one of New York's leading portrait painters. Jarvis, recognizing the boy's potential, offered him an apprenticeship. This seven-year term under Jarvis's tutelage provided Inman with a rigorous and practical artistic education, laying the foundation for his future success.

Apprenticeship with John Wesley Jarvis and Early Collaborations

John Wesley Jarvis (c. 1780-1840) was a flamboyant and highly productive artist, known for his rapid execution and ability to capture a sitter's character. Under Jarvis, Inman learned the craft of portraiture from the ground up. The master-apprentice relationship was common at the time, and Inman's duties would have included grinding pigments, preparing canvases, and eventually, painting drapery and backgrounds for Jarvis's portraits. This hands-on experience was invaluable.

Jarvis often traveled for commissions, and Inman accompanied him, gaining exposure to different parts of the country and a diverse clientele. Their collaboration was efficient; Jarvis would typically paint the head, considered the most crucial part of the portrait, while Inman would complete the remainder of the canvas. This division of labor allowed them to produce a remarkable number of portraits, sometimes as many as six per week. This period honed Inman's technical skills and his understanding of the business of art. By 1817, while still an apprentice, Inman was already creating his own significant works, including his first large oil portrait.

Upon completing his apprenticeship in 1821, Inman was well-prepared to launch his independent career. In 1822, he married Jane Riker O’Brien and established his own studio in New York City. Initially, he partnered with Thomas Geer, though this partnership was short-lived. A more significant professional association began in 1824 when he formed a partnership with Thomas Seir Cummings (1804-1894), who had been his fellow apprentice under Jarvis. Cummings specialized in miniature painting, a highly sought-after art form, while Inman focused increasingly on larger oil portraits. Their joint studio catered to a broad range of clients. This partnership lasted until about 1827, after which both artists pursued more independent paths, though they remained lifelong friends and colleagues.

Rise as a Premier Portrait Painter

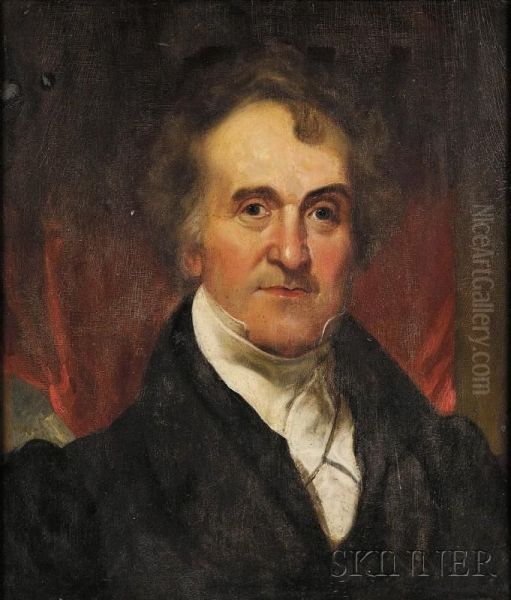

By the mid-1820s, Henry Inman had established himself as one of New York's foremost portrait painters. His style was characterized by a pleasing naturalism, an ability to capture not just a likeness but also the personality and social standing of his sitters. His portraits were often imbued with a sense of relaxed elegance and psychological insight that appealed to the increasingly affluent and sophisticated clientele of the era. He painted many of the leading figures of his day, including politicians, clergymen, writers, and prominent citizens.

Among his notable sitters were President Martin Van Buren, Chief Justice John Marshall, and the author Fitz-Greene Halleck. His portrait of William Wirt, the former U.S. Attorney General, is considered one of his masterpieces, showcasing his skill in rendering both physiognomy and character. Inman's portraits were admired for their warm flesh tones, skillful handling of light and shadow, and the refined rendering of textures, particularly in fabrics and attire. He was adept at creating compositions that were both dignified and engaging.

His success was not limited to male sitters. Inman also excelled in portraying women and children, often infusing these works with a particular sensitivity and charm. His ability to connect with his subjects and translate their essence onto canvas made him highly sought after. The demand for his work was such that he was able to command substantial fees, reflecting his status in the American art world. His style, while rooted in the English portrait tradition exemplified by artists like Sir Thomas Lawrence, was adapted to an American sensibility, less grandiose but no less accomplished.

The National Academy of Design: A Founding Father

Beyond his personal artistic achievements, Henry Inman played a vital role in the institutional development of American art. In 1826, he was among the group of artists, including Samuel F.B. Morse (1791-1872) and Asher B. Durand (1796-1886), who founded the National Academy of Design in New York City. This institution was established by artists, for artists, in response to the perceived inadequacies of the existing American Academy of Fine Arts, which was largely controlled by non-artist patrons.

The National Academy aimed to provide professional training for artists, organize regular exhibitions of contemporary American art, and elevate the status of artists in society. Inman was elected its first vice-president, a position he held for several years, with Morse serving as president. Inman was deeply committed to the Academy's mission, teaching in its schools and actively participating in its governance. His involvement underscored his dedication to fostering a supportive and professional environment for American artists. The Academy quickly became the leading art institution in the country, and Inman's role in its early years was crucial to its success and enduring influence. Other prominent early members included Thomas Cole (1801-1848), the founder of the Hudson River School, and John Trumbull (1756-1843), though Trumbull was more associated with the older American Academy.

Diversification: Genre Scenes, Landscapes, and Miniatures

While portraiture remained the mainstay of his career and his primary source of income, Henry Inman was a versatile artist who explored other genres with considerable skill. He produced charming genre scenes, depicting everyday life and anecdotal narratives. One of his most famous works in this vein is The News Boy (1841), a sentimental yet keenly observed portrayal of a young newspaper vendor. Such paintings resonated with the public's growing interest in American subjects and narratives.

Inman also painted landscapes, often imbued with a romantic sensibility. These works, while fewer in number than his portraits, demonstrate his appreciation for nature and his ability to capture atmospheric effects. His Children in a Park (1824) is an early example that showcases his delicate handling of color and light in an outdoor setting. His landscape work, though not as central to his oeuvre as it was for contemporaries like Thomas Doughty (1793-1856) or later Hudson River School painters, shows his engagement with the burgeoning American landscape tradition.

Furthermore, Inman continued to practice miniature painting throughout his career, a skill he likely refined during his early association with Thomas Seir Cummings. Miniatures, typically painted in watercolor on ivory, were highly valued as intimate keepsakes. Inman's miniatures were praised for their exquisite detail and delicate execution, demonstrating his mastery across different scales and media. This versatility distinguished him from many of his contemporaries who specialized more narrowly.

The Philadelphia Interlude and Lithography

In 1831, seeking new opportunities and perhaps a change of scene, Henry Inman relocated his family to Philadelphia. He resided there for about three years, quickly establishing himself within the city's artistic and social circles. During this period, he formed a partnership with the prominent Philadelphia lithographer Cephas G. Childs (1793-1871). Lithography was a relatively new printmaking technique that was gaining popularity for its ability to reproduce images with subtlety and detail.

Their collaboration resulted in the publication of numerous prints, including portraits and other subjects. Most significantly, Inman and Childs undertook the monumental task of creating lithographic reproductions for Thomas L. McKenney and James Hall's History of the Indian Tribes of North America (published 1836-1844). This ambitious project involved Inman copying many of the original oil portraits of Native American leaders that Charles Bird King (1785-1862) had painted in Washington D.C. Inman's watercolor copies served as the basis for the hand-colored lithographs in the publication. This project was a significant undertaking, contributing to the visual record of Native American cultures, though it was part of a complex and often fraught history of representation. Artists like George Catlin (1796-1872) were also contemporaneously documenting Native American life, often with a different, more ethnographic approach.

Return to New York, Continued Success, and Challenges

Around 1834, Henry Inman returned to New York City, where he resumed his position as one of the city's leading artists. He continued to receive numerous commissions for portraits and remained active in the National Academy of Design. He also took on students, passing on his knowledge and experience to the next generation of artists. Among those who studied with him were Thomas Whitmore King and William Temple Gibbs. His influence extended to younger portraitists like Charles Loring Elliott (1812-1868), who admired Inman's style.

Despite his professional success, Inman faced personal challenges. He had a penchant for speculation, particularly in land, and suffered significant financial losses during the economic Panic of 1837. This financial instability, coupled with the demands of supporting a large family, placed considerable strain on him. Furthermore, Inman struggled with chronic asthma throughout his life, and his health began to deteriorate more seriously in the 1840s. Nevertheless, he continued to work tirelessly, driven by both artistic ambition and financial necessity. His contemporary Thomas Sully (1783-1872), based primarily in Philadelphia but well-known in New York, also enjoyed a long and successful career in portraiture, navigating similar economic landscapes.

The London Sojourn

In an effort to improve his health and perhaps seek new patronage, Henry Inman traveled to England in 1844. This was a significant undertaking, reflecting his established reputation. During his time in London, which lasted about a year, he had the opportunity to study the works of British masters and to paint portraits of several distinguished Englishmen.

Among his most notable commissions in England were portraits of the historian Lord Macaulay and the poet William Wordsworth. His portrait of Wordsworth, painted at Rydal Mount, is considered one of the definitive likenesses of the aged poet. Inman also painted other figures and reportedly received favorable attention in London's art circles. This experience abroad, though relatively brief, provided him with fresh inspiration and a broader perspective on the art world. It also connected him, however briefly, to the lineage of Anglo-American portraiture that included earlier figures like Benjamin West (1738-1820) and Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828), both of whom had significant careers in London.

Final Years and Enduring Legacy

Henry Inman returned to New York in 1845, his health unfortunately not substantially improved. He resumed his work, but his strength was failing. He passed away prematurely on January 17, 1846, at the age of 44, in New York City. His death was a significant loss to the American art community. The National Academy of Design organized a memorial exhibition of his works, a testament to the high regard in which he was held by his peers. This exhibition, featuring over 120 of his paintings, was one of the first major retrospectives for an American artist and helped to solidify his posthumous reputation.

Henry Inman's legacy is multifaceted. As a portraitist, he captured the likenesses of a generation of Americans, creating a valuable visual record of his time. His ability to combine technical skill with psychological insight set a high standard for American portraiture. Artists like Daniel Huntington (1816-1906), who was a younger contemporary and also served as President of the National Academy, can be seen as continuing in a similar tradition of refined portraiture.

His contributions to genre and landscape painting, though less extensive, demonstrated his versatility and his engagement with broader artistic trends. Perhaps most importantly, his role as a founder and leader of the National Academy of Design had a lasting impact on the professionalization of art in America. He helped to create an institutional framework that supported artists and promoted American art. His work is held in major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Portrait Gallery, and the White House. He remains a key figure in understanding the development of American art in the antebellum period, a bridge between the colonial era painters like John Singleton Copley (1738-1815) and the more diverse artistic landscape of the later 19th century. His contemporary, Rembrandt Peale (1778-1860), of the famed Peale family of artists, also contributed significantly to American portraiture during this era.

Inman's Artistic Style and Techniques

Henry Inman's artistic style was characterized by its blend of realism and a subtle romanticism. In portraiture, his primary aim was to achieve a faithful likeness, but he went beyond mere verisimilitude to capture the sitter's character and social presence. His figures often possess a sense of vitality and animation. He employed a fluid brushwork and a warm, rich palette, particularly in rendering flesh tones. His compositions were generally straightforward but effective, often utilizing conventional poses and settings that nonetheless felt natural and unforced.

Inman paid careful attention to the rendering of details, such as clothing, accessories, and background elements, which helped to contextualize his sitters and convey their status. However, these details rarely overwhelmed the central focus on the sitter's face and expression. He was skilled in the use of chiaroscuro, employing light and shadow to model forms and create a sense of depth.

In his genre scenes, like The News Boy, there is a narrative quality and often a touch of sentimentality that appealed to contemporary tastes. These works demonstrate his skills in figure composition and storytelling. His landscapes, while less numerous, show an appreciation for the American scenery and an ability to convey mood and atmosphere, often with a soft, diffused light.

His miniatures on ivory showcase a different aspect of his technical prowess: meticulous detail, delicate stippling, and a luminous quality achieved through the transparency of watercolors on the ivory support. Across all genres, Inman's work is marked by a high level of craftsmanship and an accessible, engaging quality that made him one of the most popular and respected artists of his time. He successfully navigated the artistic tastes of a democratic society, creating art that was both accomplished and appealing.

Conclusion: A Pivotal Figure in American Art

Henry Inman's career, though spanning just over two decades, was immensely productive and influential. He emerged as a leading figure in the New York art world at a time when the city was becoming the nation's cultural capital. His portraits defined a generation, his genre scenes captured the American spirit, and his leadership helped to shape the institutions that would support American artists for decades to come. Despite personal hardships, his dedication to his art and his profession never wavered. Henry Inman remains an essential artist for understanding the aspirations, character, and visual culture of early 19th-century America, a true master whose work continues to resonate with its skill, insight, and enduring charm.