Hugh Henry Breckenridge (1870-1937) stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the narrative of American art. A painter and influential teacher, he navigated the transformative artistic currents from the late 19th century into the early 20th century, evolving from a gifted Impressionist to a bold explorer of Modernist abstraction. His career, deeply rooted in Philadelphia, demonstrates a relentless pursuit of color's expressive potential and a commitment to artistic innovation that left a lasting mark on his students and the broader American art scene.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Born in Leesburg, Virginia, on October 6, 1870, Hugh Henry Breckenridge embarked on his artistic journey at a young age. His family's move to Philadelphia proved fortuitous, placing him in proximity to one of the nation's premier art institutions. In 1887, at the age of seventeen, he enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA). This institution, already steeped in a rich tradition fostered by artists like Thomas Eakins and, later, Thomas Anshutz, provided Breckenridge with a rigorous academic grounding.

At PAFA, Breckenridge distinguished himself as a promising talent. His dedication and skill were recognized in 1889 when he was awarded the prestigious Cresson Traveling Scholarship. This scholarship was a critical stepping stone for many aspiring American artists, affording them the opportunity to experience European art firsthand. For Breckenridge, this meant a journey to Paris, the undisputed epicenter of the art world at the time.

Parisian Sojourn and the Embrace of Impressionism

In 1892, Breckenridge arrived in Paris and enrolled at the Académie Julian, a popular choice for international students, including many Americans. There, he studied under renowned academic painters such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau. While Bouguereau represented the established academic tradition, Paris was simultaneously a hotbed of avant-garde activity. The Impressionist revolution, spearheaded by artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas, had already reshaped the landscape of painting, and its aftershocks were still being felt, with Post-Impressionist figures like Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin pushing boundaries further.

Breckenridge absorbed these influences, particularly the Impressionists' fascination with light, color, and capturing fleeting moments. He learned to lighten his palette and employ broken brushwork, techniques that would characterize his early mature style. His time in Europe, which also included travel to Italy and Holland with fellow PAFA student Walter Elmer Schofield, was formative, equipping him with a modern sensibility that he would bring back to the United States.

A Distinguished Teaching Career

Upon his return to America, Breckenridge quickly established himself not only as a painter but also as a dedicated and influential educator. In 1894, he began what would become a remarkable 43-year tenure as an instructor at his alma mater, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. His commitment to teaching was profound, and he rose through the ranks, eventually becoming Dean of Instruction in 1934, a position he held until his death.

Breckenridge's impact as a teacher was immense. He was known for his open-mindedness and his encouragement of experimentation among his students. He did not impose a single style but rather fostered an environment where young artists could find their own voices. Among his many students who went on to achieve recognition was Arthur B. Carles, who would become a close friend and a fellow pioneer of Philadelphia modernism. Carles himself credited Breckenridge with teaching him that "color resonance is the major interest in painting."

Beyond PAFA, Breckenridge extended his educational efforts. In 1900, alongside his former PAFA instructor Thomas Anshutz, he co-founded the Darby School of Painting in Darby, Pennsylvania. This summer school, later known as the Breckenridge School of Art when it moved to East Gloucester, Massachusetts, became an important center for plein-air painting and attracted students from across the country. It was particularly associated with the Pennsylvania Impressionist movement, though Breckenridge's own teaching and art would evolve far beyond traditional Impressionism. His summer classes in Gloucester allowed him and his students to explore the unique light and coastal scenery of New England, a popular subject for American Impressionists like Childe Hassam and John Henry Twachtman.

Artistic Evolution: From Impressionism's Light to Modernism's Structure

Hugh Henry Breckenridge's artistic output is notable for its stylistic diversity and his willingness to embrace change. His long career can be seen as a continuous exploration of the fundamental elements of painting, particularly color, light, and form.

The Impressionist Phase

In the earlier part of his career, Breckenridge was a leading exponent of American Impressionism. His landscapes, portraits, and genre scenes from this period are characterized by a vibrant palette, luminous light effects, and a concern for capturing the atmosphere of the moment. Works like The Open Garden exemplify this phase. This painting, likely depicting his own garden, "Phloxdale," in Fort Washington, a suburb of Philadelphia, showcases his mastery of Impressionist techniques. It is filled with dappled sunlight, lush foliage rendered in vivid greens and floral hues, and an overall sense of immediacy and natural beauty. His approach was akin to that of other American Impressionists such as Willard Metcalf or Frank W. Benson, who adapted French Impressionist principles to American subjects and light.

His portraits from this era, while often adhering to more traditional compositional structures, also benefited from his heightened sense of color and his ability to capture the personality of the sitter. He received numerous accolades for these works, including medals at various national and international expositions.

A Deepening Exploration of Color and Form

As the 20th century progressed, Breckenridge's art began to reflect the burgeoning interest in more subjective and expressive uses of color, as well as a greater emphasis on formal structure. While he never fully abandoned representation during this transitional period, his works became increasingly bold in their chromatic choices and compositional arrangements.

Still life painting became a particularly important vehicle for his experiments. Works such as The White Vase and Blue and Gold (1916) demonstrate this shift. In these paintings, the objects themselves – flowers, vases, drapery – serve as starting points for intricate explorations of color harmonies and contrasts. Blue and Gold, for instance, was a gift to his wife, Roxana Grace Breckenridge (also an artist), and was later gifted by her class of 1916 to the Nebraska State Normal School (now the University of Nebraska at Kearney). These paintings reveal an artist increasingly interested in the abstract qualities of his subjects, pushing color towards a more independent, emotive role, somewhat analogous to the Fauvist experiments of Henri Matisse and André Derain in France, or the color-centric theories of Synchromists like Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Morgan Russell in America.

Breckenridge's evolving understanding of color was not merely intuitive; it was also intellectual. He developed theories about color relationships and their psychological impact, which he shared with his students. He believed that color was the painter's primary means of expression, capable of evoking profound emotional responses.

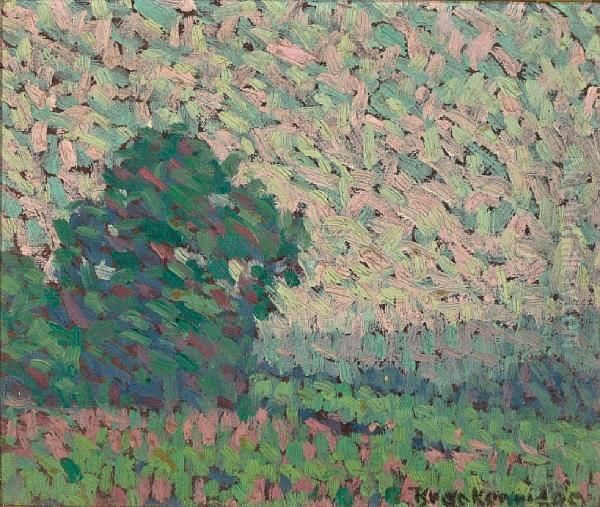

The Embrace of Abstraction

By the 1920s, Breckenridge was moving decisively towards abstraction, becoming one of the earliest American artists to consistently explore non-representational painting. This was a significant leap, particularly for an artist with such a strong foundation in academic and Impressionist traditions. His abstract works are characterized by dynamic compositions, rich textures, and an even more intensified focus on color.

A key work from this period is Arrangement (c. 1927-28). In this painting, the still life elements are transformed into a vibrant tapestry of interlocking shapes and resonant colors. The subject matter is almost entirely subsumed by the formal concerns of line, shape, and, above all, color. These works often featured a jewel-like palette and a sense of rhythmic energy. He also explored themes inspired by Cubism, as seen in a series of abstract paintings based on the forms of boats and harbors, likely inspired by his summers in Gloucester. These works show an engagement with the structural innovations of European modernists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, but translated into Breckenridge's own distinctive color-driven language.

His commitment to modernism was further evidenced by his participation in important exhibitions. In 1927, he was one of seven artists featured in a significant exhibition of Philadelphia modernists at the Wildenstein Gallery in New York. This show helped to highlight Philadelphia's role as an important center for progressive art in America, a scene that also included artists like Arthur B. Carles, Henry McCarter, and Charles Demuth (though Demuth was more closely associated with the Stieglitz circle in New York).

Throughout the 1930s, Breckenridge continued to produce abstract and highly expressionistic still lifes and landscapes. His work Painted Autumn (1931), exhibited at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, exemplifies his mature abstract style, where the essence of the season is conveyed through pure color and dynamic form rather than literal depiction. He often spoke of his art as a direct response to nature and life, aiming to evoke an emotional resonance in the viewer.

Collaborations and Contemporaries

Breckenridge was an active participant in the artistic community of his time. His most significant professional relationship was arguably with Arthur B. Carles. Both were influential teachers at PAFA, and they shared a profound interest in color theory and modernist experimentation. They are often considered the leading figures of Philadelphia Modernism. Their work was featured together in posthumous exhibitions, such as "Living Color, Modern Life: Hugh Henry Breckenridge and Arthur B. Carles," which underscored their shared journey and mutual influence.

His collaboration with Thomas Anshutz in founding the Darby School of Painting was also crucial. Anshutz, himself a student of Thomas Eakins and an important teacher, provided a link to an earlier generation of American realism, while Breckenridge represented the newer, more color-oriented approaches. The school fostered a spirit of camaraderie and shared exploration among its faculty and students.

Breckenridge's career overlapped with many other significant American artists. In the realm of Impressionism, he was a contemporary of figures like Childe Hassam, John Henry Twachtman, J. Alden Weir (all members of "The Ten American Painters"), and William Merritt Chase, who was also an influential teacher at PAFA for a time. As modernism took hold in America, Breckenridge's explorations ran parallel to, though often distinct from, those of artists in Alfred Stieglitz's circle, such as Georgia O'Keeffe, John Marin, Marsden Hartley, and Arthur Dove. While these artists often focused on a uniquely American form of modernism, Breckenridge's path was deeply informed by his Philadelphia base and his continuous engagement with European developments.

He was not known for overt competition but rather for a dedicated pursuit of his own artistic vision and a generous spirit as an educator. His refusal to strictly categorize art or to adhere rigidly to any single "ism" might have contributed to his somewhat lower profile in some art historical narratives, which often favor artists who fit neatly into specific movements. He believed that such classifications were too restrictive and hindered the free expression of the artist.

Later Years and Legacy

Hugh Henry Breckenridge remained an active artist and teacher until his death in Philadelphia on November 4, 1937. His later works continued to explore the expressive power of color, often in highly abstract compositions that pulsed with energy and light.

His legacy is multifaceted. As an educator, he influenced generations of artists, instilling in them a respect for craftsmanship, an adventurous approach to color, and the courage to experiment. His long tenure at PAFA and his leadership at the Breckenridge School of Art ensured that his ideas had a wide reach.

As an artist, Breckenridge's journey from academic realism through Impressionism to a distinctive form of abstraction mirrors the broader transformations in American art during his lifetime. He was a pioneer in the American modernist movement, particularly in his early and sustained commitment to abstract painting. His deep understanding of color theory and his ability to translate that understanding into visually compelling artworks set him apart.

While some of his works, like The Open Garden, remain celebrated examples of American Impressionism, his abstract paintings are increasingly recognized for their innovation and beauty. His work can be found in the collections of major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Auction records for his works, including pieces like The White Vase (which has appeared at Sotheby's in London and Hong Kong), attest to a continued appreciation for his art in the market.

Hugh Henry Breckenridge's career is a testament to a lifelong dedication to artistic growth and the expressive power of color. He was a vital link between 19th-century traditions and 20th-century modernism, a respected teacher, and an artist whose vibrant and innovative works continue to engage and inspire. His contributions were crucial to the development of a distinctly American modern art, particularly in the vibrant artistic milieu of Philadelphia.