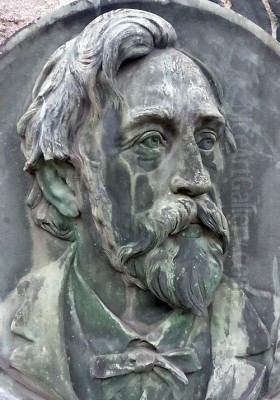

The annals of art history are replete with celebrated masters whose lives and works are meticulously documented. Yet, for every luminary, there exist countless other artists whose contributions, though perhaps more modest or less visible to posterity, formed the rich tapestry of a city's cultural life. Ignaz Ellminger appears to be one such figure, an artist active in Vienna, whose presence is primarily attested through a few tantalizing archival mentions. While a comprehensive biography remains elusive, the available fragments allow us to sketch a portrait of a professional working within the vibrant artistic milieu of the Austro-Hungarian capital.

The Viennese Context: A Crucible of Art

To understand any artist, one must first appreciate the environment in which they worked. Vienna around the late 19th and early 20th centuries was a city of immense artistic ferment. It was the era of the Ringstrasse, with its grand historicist buildings demanding decorative schemes, and the burgeoning of modern thought that would soon give rise to the Vienna Secession. Artists like Hans Makart dominated the official scene with his opulent historical paintings, while a younger generation, including figures such as Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, and Oskar Kokoschka, were beginning to challenge established norms.

The academic tradition, upheld by institutions like the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, still held considerable sway. Masters such as Christian Griepenkerl or Leopold Carl Müller trained generations of painters. Concurrently, realism and naturalism found exponents in artists like Emil Jakob Schindler and August von Pettenkofen, who focused on landscape and genre scenes. The graphic arts, too, were flourishing, with a strong tradition of printmaking and drawing. It is within this dynamic and multifaceted artistic landscape that we must situate Ignaz Ellminger.

A Professional in Freehand Drawing

The most concrete piece of information regarding Ignaz Ellminger's profession identifies him as a practitioner of "Freihand-zeichnen," or freehand drawing. This skill was fundamental, not only for fine artists but also for architects, designers, and various craftsmen. An entry lists "Ellminger Ignaz, für Freihand-zeichnen, IX, Spitalgasse 33." This address places him in the Alsergrund district of Vienna, a populous area with a mix of residential buildings, hospitals (hence "Spitalgasse" or Hospital Street), and workshops.

The designation "für Freihand-zeichnen" could imply several roles. He might have been a professional draughtsman, creating preparatory sketches, illustrations, or finished drawings for various purposes. Alternatively, and perhaps more likely given the phrasing, he could have been a teacher or professor of freehand drawing. Private art tuition was common, and specialized instruction in drawing would have been in demand. Whether he taught independently from his Spitalgasse address or was affiliated with a specific institution is not specified. The ability to draw accurately and expressively from life or imagination was a cornerstone of artistic training, a skill honed through rigorous practice. Artists like Adolph Menzel in Germany, for instance, were renowned for their prodigious drawing abilities, which formed the backbone of their painted work.

The Artistic Estate: An Auction in 1907

A significant clue to Ellminger's artistic output comes from a record of an auction. On February 25th and 26th, 1907, the "Künstlerischer Nachlass" (artistic estate) of Ignaz Ellminger, along with works from the estate of Franz Russ and others, was auctioned by the firm Antikost in Vienna. The items from Ellminger's estate included oil paintings, drawings, and watercolors. This event is crucial for several reasons.

Firstly, the auction of an "artistic estate" often, though not always, implies that the artist was deceased, and his remaining works were being sold off. If this is the case, it would place Ellminger's activity primarily in the latter half of the 19th century, culminating before 1907. Secondly, the range of media – oils, watercolors, and drawings – suggests a versatile artist, not solely confined to draughtsmanship as a preparatory discipline but also engaging with painting.

The nature of these works remains unknown. Were they academic studies, landscapes, portraits, or genre scenes? Without a catalogue or specific titles, we can only speculate. However, the fact that his works were deemed worthy of inclusion in a public auction alongside those of Franz Russ (likely Franz Russ the Elder or Younger, both established Viennese painters) indicates a certain level of professional standing. Franz Russ the Elder (1817-1892) was known for historical and genre scenes, while Franz Russ the Younger (1843-1906) painted portraits and genre works, often with a sentimental or anecdotal character. Ellminger's association, even in an auction context, with such figures provides a slight hint towards the artistic circles he might have moved in or the type of art he produced.

The auction house Antikost, while perhaps not as prestigious as galleries like the Galerie Miethke (which famously supported Klimt and the Secessionists), played a role in the Viennese art market. The mention of "Sedelmeyer (Paris und Wien)" in relation to Ellminger in one source is also intriguing. Charles Sedelmeyer was a prominent international art dealer with galleries in Paris and connections to Vienna. If Ellminger's work was handled or known by Sedelmeyer, it would suggest a broader reach or recognition beyond local Viennese circles. Sedelmeyer was known for dealing in Old Masters but also in contemporary academic and salon painters, such as Mihály Munkácsy or Jehan Georges Vibert.

Speculating on Style and Subject

Given his profession as a specialist in freehand drawing and the general artistic climate of Vienna during his likely period of activity, we can make some educated guesses about Ellminger's potential artistic style. If he was active in the mid-to-late 19th century, his training would likely have been grounded in academic principles, emphasizing accurate representation, perspective, and anatomical correctness. His drawings might have ranged from meticulous studies to more expressive sketches.

His oil paintings and watercolors could have explored various genres popular at the time. Landscape painting was highly favored, with artists like Rudolf von Alt producing detailed and atmospheric views of Austrian cities and countryside. Portraiture was always in demand, and genre scenes depicting everyday life or historical narratives were also common. Without specific examples of his work, it is difficult to ascertain whether he leaned towards the prevailing historicism, the emerging realism, or perhaps even early intimations of Impressionism, which was slowly making its way into Vienna through artists like Theodor von Hörmann.

The fact that he was a "Professor für Freihand-zeichnen" might also suggest that a significant portion of his output could have been didactic, perhaps model drawings or studies intended for instructional purposes. Such works, while crucial for teaching, are often less valued in the art market than finished exhibition pieces, which might contribute to an artist's relative obscurity.

The Challenge of Reconstructing a Minor Master

The case of Ignaz Ellminger highlights the challenges faced by art historians when attempting to reconstruct the careers of artists who did not achieve widespread or lasting fame. Many skilled and productive artists operated outside the main currents that later came to define art historical narratives. Their works may be dispersed, unattributed, or held in private collections, making comprehensive study difficult.

The survival of an artist's reputation often depends on factors beyond mere talent: patronage, critical reception, participation in influential exhibitions, association with prominent movements, and the preservation of their archives. For artists like Ellminger, whose presence is marked by a few sparse records, each piece of information becomes a vital clue. The mention of his address, his specialization, and the auction of his estate are the building blocks from which a tentative understanding can be constructed.

Further research, were it possible, might involve scouring Viennese city directories (Lehmann's Allgemeiner Wohnungs-Anzeiger, for example) for more precise dates of his residency at Spitalgasse 33. Searching for catalogues of the Antikost auction in 1907, if any survive, could yield titles or descriptions of his works. Investigating the records of the Academy of Fine Arts or other teaching institutions in Vienna might reveal an affiliation. The connection to Sedelmeyer could also be a fruitful avenue, exploring the dealer's Viennese activities and acquisitions.

It is also worth considering the broader context of draughtsmanship in Vienna. The city had a strong graphic tradition, with artists like Josef Danhauser in the Biedermeier period being excellent draughtsmen. Later, figures associated with the Vienna Secession, such as Koloman Moser and Josef Hoffmann, placed enormous emphasis on drawing as the foundation for their designs in various media. While Ellminger likely preceded the full flowering of the Secession, the underlying respect for drawing was a constant.

Conclusion: A Glimpse of a Viennese Artist

Ignaz Ellminger remains a figure largely in the shadows, a name associated with freehand drawing in Vienna and an artistic estate auctioned in the early 20th century. While we lack the specific details of his major works, his artistic style, or his direct influence, the available information allows us to place him as a professional artist and possibly an educator within the rich cultural fabric of Vienna. He was likely a skilled draughtsman, proficient in oil and watercolor, operating in a city that was a major European art center.

His story, though incomplete, reminds us that the art world is composed not only of its most famous protagonists but also of a multitude of other dedicated practitioners who contributed to its vitality. The auction of his works alongside those of Franz Russ suggests a recognized professional standing. The mention of his address on Spitalgasse gives us a tangible link to his physical presence in the city. Ignaz Ellminger, the Viennese master of freehand drawing, may not be a household name like Klimt or Schiele, but he represents an important stratum of artistic activity that deserves acknowledgement. His legacy, however fragmented, offers a glimpse into the life of a working artist in one of Europe's most artistically vibrant capitals at a time of significant cultural transition. Further discoveries may one day illuminate more fully the life and art of this intriguing Viennese figure.