Ilya Yefimovich Repin stands as a towering figure in the history of Russian art, arguably the most renowned and influential Russian painter of the 19th century. Born into a period of significant social and political change, Repin became a leading light of the Realist movement in Russia, particularly associated with the Peredvizhniki (The Wanderers or The Itinerants) society. His vast body of work, encompassing monumental historical canvases, penetrating psychological portraits, and scenes of contemporary life, captured the spirit, struggles, and soul of Russia in a way few artists ever have. His commitment to depicting truth, his profound empathy for his subjects, and his exceptional technical skill cemented his legacy as a national icon and an artist of international importance.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Ilya Repin was born on August 5, 1844 (July 24, Old Style), in the town of Chuguev, near Kharkov, in what is now Ukraine but was then part of the Russian Empire. His family background was modest; his father was a military settler, a specific social class in Tsarist Russia involving military service combined with farming. This upbringing exposed the young Repin to the hardships of provincial life and the realities faced by ordinary people, experiences that would deeply inform his later work. Despite the family's limited means, his early talent for drawing was recognized and encouraged.

He received his initial artistic training locally, working with an icon painter named Ivan Bunakov and later assisting with the painting of church frescoes. This early exposure to religious art likely honed his skills in composition and figure drawing. However, Repin harbored ambitions beyond provincial icon painting. Driven by a desire for formal academic training, he saved money and, in 1863, at the age of 19, made the arduous journey to the imperial capital, Saint Petersburg.

His goal was the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts. Although initially failing the entrance exams, Repin persevered, taking lessons at the drawing school of the Society for the Encouragement of Artists, where he met the influential art critic Vladimir Stasov, who would become a lifelong friend and champion. He also encountered Ivan Kramskoi, a leading figure in the burgeoning Realist movement, who became an important mentor. Repin finally gained admission to the Academy in 1864, studying under artists like Fyodor Bruni and Alexey Markov, though he found the Academy's strict neoclassical curriculum often stifling.

The Academy Years and European Travels

During his time at the Academy, Repin quickly distinguished himself. He absorbed the technical skills offered but increasingly gravitated towards subjects drawn from Russian life and history, rather than the mythological or biblical scenes favored by the academic establishment. He won several awards, culminating in the Large Gold Medal in 1871 for his painting The Raising of Jairus's Daughter. This award granted him a scholarship for six years of study abroad.

Before embarking on his European tour, however, Repin undertook a journey that would result in his first major masterpiece. In the summer of 1870, encouraged by Kramskoi and Stasov, he traveled down the Volga River. There, he witnessed the grueling labor of the burlaki, men who hauled barges upstream against the current. Deeply moved by their plight and their stoic dignity, he began sketches for what would become Barge Haulers on the Volga. Completed in 1873, this painting, with its unvarnished depiction of human toil and its powerful character studies, caused a sensation and established Repin as a major new voice in Russian art.

From 1873 to 1876, Repin traveled through Europe, spending time primarily in Italy and France. In Vienna, he saw works by Old Masters, and in Rome, he studied classical art. Paris exposed him to the contemporary art scene, including the burgeoning Impressionist movement. While he admired the Impressionists' handling of light and color, particularly artists like Édouard Manet, Repin ultimately found their focus on fleeting moments and sensory perception incompatible with his own desire to explore deeper psychological and social themes. He remained committed to the narrative power and social engagement of Realism, though his palette sometimes brightened, and his brushwork loosened slightly following his European experience.

The Peredvizhniki and the Height of Realism

Upon his return to Russia in 1876, Repin settled initially in his hometown of Chuguev before moving back to Moscow and later Saint Petersburg. He formally joined the Society for Traveling Art Exhibitions (the Peredvizhniki) in 1878, although he had been associated with its members, like Ivan Kramskoi and Vasily Polenov, for years. The Peredvizhniki aimed to break free from the constraints of the Academy, bring art to the provinces, and depict the realities of Russian life with truthfulness and social conscience. Repin became one of the movement's central figures.

This period marked the height of Repin's creative powers, during which he produced some of his most iconic and ambitious works. He tackled complex historical subjects, contemporary social issues, and revolutionary themes with equal mastery. Religious Procession in Kursk Governorate (1880-1883) is a sweeping panorama depicting a diverse cross-section of Russian society – clergy, officials, peasants, beggars, and the infirm – participating in a religious procession carrying a famed icon. The painting is a complex commentary on faith, social hierarchy, and the human condition, notable for its detailed characterizations and vibrant, almost chaotic energy.

Another powerful work exploring revolutionary themes is Arrest of a Propagandist (1880-1892), depicting the capture of a populist revolutionary in a peasant hut. The tension and varied reactions of the onlookers – suspicion, fear, curiosity, sympathy – create a compelling social drama. Similarly, They Did Not Expect Him (or Unexpected Return, 1884-1888) captures the emotionally charged moment when a political exile returns unannounced to his family. The psychological depth in the portrayal of the family's shock, uncertainty, and dawning recognition is remarkable.

Masterpieces of Historical Drama and Psychological Intensity

Repin possessed an extraordinary ability to delve into the psychological depths of historical events. His most famous, and perhaps most controversial, historical painting is Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on November 16, 1581 (completed 1885). Inspired partly by the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 and Rimsky-Korsakov's music, the painting depicts the legendary moment after the Tsar, in a fit of rage, has struck his son a fatal blow. The raw horror, grief, and remorse in Ivan's eyes, contrasted with the life draining from his son, create an image of shocking emotional power. The painting's graphic intensity provoked strong reactions and was even attacked by vandals on two separate occasions, in 1913 and 2018, highlighting its enduring ability to disturb and fascinate.

Another major historical work, showcasing a different mood, is Zaporozhian Cossacks Writing a Mocking Letter to the Sultan of Turkey (1880-1891). Based on a legendary incident from the 17th century, the painting depicts Ukrainian Cossacks roaring with laughter as they collaboratively draft an insulting reply to the Ottoman Sultan. Repin meticulously researched Cossack history and physiognomy, creating a vibrant, Rabelaisian scene brimming with life, defiant spirit, and individual character. It celebrates freedom and camaraderie, contrasting sharply with the somber tones of many of his other works.

Later in his career, Repin undertook large-scale official commissions, most notably the Ceremonial Sitting of the State Council on 7 May 1901 (1903). This monumental group portrait, commemorating the centenary of the State Council, involved dozens of individual studies and showcases Repin's undiminished skill in capturing likeness and character even within a formal state setting. He collaborated with his students Boris Kustodiev and Ivan Kulikov on this massive undertaking.

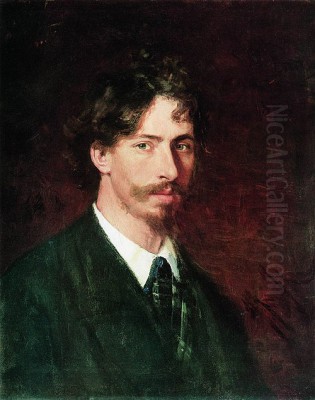

The Portraitist of an Era

Alongside his large narrative canvases, Repin was a prolific and highly sought-after portrait painter. He possessed an uncanny ability to capture not just the physical likeness but also the inner life and personality of his sitters. He painted emperors (Alexander III, Nicholas II), aristocrats, leading intellectuals, writers, scientists, and fellow artists, creating a veritable gallery of the prominent figures of his time.

His portraits of Leo Tolstoy are particularly famous. Repin visited the writer at his Yasnaya Polyana estate multiple times, creating numerous sketches and several finished portraits, including the iconic image of Tolstoy barefoot and plowing a field, and another depicting him reading in his study. These works convey Tolstoy's complex personality – the sage, the nobleman, the seeker of truth.

Equally powerful is his deathbed portrait of the composer Modest Mussorgsky (1881), painted just days before Mussorgsky's death from alcoholism. Despite the sitter's ravaged appearance, Repin captures an intense spark of creative genius and vulnerability. Other notable portraits include those of the critic Vladimir Stasov, the chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, the surgeon Nikolai Pirogov, the philanthropist Pavel Tretyakov (founder of the Tretyakov Gallery), and fellow artists like Ivan Kramskoi, Vasily Surikov, and Nikolai Ge. Each portrait is a penetrating psychological study, rendered with technical brilliance.

Teaching and Influence

Repin's influence extended beyond his own canvases. From 1894 to 1907, he served as a professor and head of the painting workshop at the reformed Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg, where he had once been a student. He was a demanding but inspiring teacher, encouraging his students to observe life closely and develop their own individual styles, while grounding them in strong drawing and compositional skills.

Many prominent Russian artists of the next generation studied under Repin or were significantly influenced by him. Among his most famous pupils were Valentin Serov, who became a celebrated portraitist in his own right, known for works like Girl with Peaches. Others included Boris Kustodiev, known for his vibrant scenes of Russian provincial life; Igor Grabar, an artist, art historian, and museum director; and Filipp Malyavin, known for his dynamic paintings of peasant women. Repin's studio became a major center of artistic life in Saint Petersburg.

His teaching methods emphasized direct observation and working from life. He encouraged outdoor sketching (plein air) and stressed the importance of capturing the essential character of the subject, whether in a portrait or a genre scene. While firmly rooted in Realism, he did not impose a rigid style, allowing talents like Serov and Kustodiev to flourish with their distinct artistic personalities.

Later Life at Penaty

In 1899, Repin purchased an estate named Penaty in Kuokkala, Finland, then an autonomous Grand Duchy within the Russian Empire, located on the Karelian Isthmus not far from Saint Petersburg. He designed the house himself and moved there permanently around 1903. Penaty became his refuge and creative sanctuary for the last thirty years of his life.

His life at Penaty was shared for a time with his second wife (common-law), the writer Natalia Nordman (pen name Severova). They embraced a somewhat eccentric lifestyle, promoting vegetarianism (serving guests "hay" cutlets), fresh air (sleeping outdoors year-round), and self-sufficiency (guests were expected to help themselves, adhering to signs like "Take coats off yourselves"). This unconventional household, while reflecting Nordman's progressive ideas, sometimes bemused or irritated visitors like the writer Kornei Chukovsky, who left vivid descriptions of life at Penaty.

After the Russian Revolution of 1917 and Finland's subsequent declaration of independence, Kuokkala became part of Finland, effectively separating Repin from Russia. Although Soviet authorities repeatedly invited him to return, offering honors and support, Repin declined. While expressing sympathy for some aspects of the revolution initially, he grew disillusioned and chose to remain in Finland. He continued to paint, though his output slowed, and his health, particularly the atrophy of his right hand which forced him to paint more with his left, presented challenges. There were even unfounded popular rumors that sitters painted with his left hand met unfortunate ends.

Controversies and Anecdotes

Repin's life and work were not without controversy. The intense realism and emotional power of Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan provoked public debate and censorship concerns from the outset. Its acquisition by Pavel Tretyakov was initially blocked by Tsar Alexander III, who found the painting repulsive, though the ban was later lifted. The subsequent attacks on the painting underscored its visceral impact.

His relationship with the Soviet regime was complex. While celebrated as a great Russian Realist whose work depicted the struggles of the people, his refusal to return to the USSR and his occasional critical remarks about the Bolsheviks complicated his official status. Nevertheless, his art, particularly works like Barge Haulers, was often interpreted through a Marxist lens as a critique of Tsarist oppression and became foundational for the later development of Socialist Realism, albeit in a simplified and dogmatic form that Repin himself might not have endorsed.

The anecdotes surrounding his life at Penaty, his vegetarianism, his relationship with Nordman, and his struggles with his health added layers to his public persona. His dedication to his art remained unwavering, even as his physical strength declined. He continued working on themes that had preoccupied him throughout his life, including religious subjects and portraits.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Repin was deeply embedded in the cultural life of his time, maintaining close relationships with many leading figures. His friendship with Vladimir Stasov was crucial; the influential critic was a staunch supporter, advisor, and frequent correspondent. His bond with Leo Tolstoy was one of mutual respect and fascination, documented in Repin's numerous portraits and sketches of the writer.

He was a central figure among the Peredvizhniki, collaborating and exhibiting alongside artists like Ivan Kramskoi, Vasily Surikov (known for his large-scale historical paintings like The Morning of the Streltsy Execution), Isaac Levitan (the master of the "mood landscape"), Nikolai Ge (painter of historical and religious subjects), and Vasily Polenov (known for landscapes and biblical scenes). While sharing the broad aims of Realism, these artists each possessed distinct styles and thematic interests, creating a rich and diverse artistic milieu. Repin's interactions with European artists during his travels also broadened his perspective, even if he ultimately forged his own path.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Ilya Repin died at Penaty on September 29, 1930, at the age of 86. He was buried on his estate. His legacy is immense and multifaceted. He is widely regarded as the preeminent Russian painter of the 19th century, the embodiment of Critical Realism. His works captured the complexities of Russian society during a period of profound transformation – its social injustices, its historical dramas, its spiritual quests, and the psychological depth of its people.

His influence on subsequent generations of Russian artists was profound, both through his teaching and the power of his example. While Soviet art later codified Realism into the doctrine of Socialist Realism, Repin's own work retained a level of psychological complexity, technical brilliance, and human empathy that transcended simple political messaging. His paintings remain cornerstones of major Russian museums, particularly the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the State Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg.

Internationally, Repin's reputation grew throughout the 20th century. His work influenced art movements beyond Russia, including the development of Realism in other countries. Notably, the Russian and Soviet academic traditions, heavily influenced by Repin and his contemporaries, had a significant impact on the development of oil painting in China during the mid-20th century. Today, his major works like Barge Haulers on the Volga and Ivan the Terrible are recognized worldwide as masterpieces of Realist art.

Conclusion

Ilya Repin's life spanned a tumultuous era in Russian history, and his art served as both a mirror and a commentary on his times. From the depiction of back-breaking labor on the Volga to the intimate portrayal of intellectual giants like Tolstoy, and from the raw emotion of historical tragedy to the boisterous energy of Cossack life, Repin embraced the full spectrum of human experience. His unwavering commitment to truth, his profound psychological insight, and his masterful technique secured his place as a titan of Russian art. His paintings continue to resonate with viewers today, offering powerful insights into the Russian soul and the enduring themes of human struggle, resilience, and spirit.