Jacob de Wit stands as one of the most significant painters of the Dutch Rococo period in the 18th century. Born in Amsterdam in 1695, he navigated a changing artistic landscape, moving away from the dominant styles of the Dutch Golden Age towards a more elegant, decorative aesthetic suited to the tastes of his time. He became particularly renowned for his ceiling and wall paintings, especially his masterful use of grisaille, earning him a lasting reputation in Dutch art history.

De Wit's journey into the art world began in a modest setting. His family belonged to the lower-middle class of Amsterdam; his father was a shoemaker, and his mother came from a family of watchmakers. This background makes his eventual rise to prominence among the wealthy elite of the city even more remarkable. His formal artistic training commenced at the young age of nine under the guidance of Albert van Spiers, an Amsterdam painter. This early instruction laid the groundwork for his technical skills.

Early Life and Training in Antwerp

A pivotal moment in de Wit's development occurred when he was thirteen. He moved to Antwerp, a city that still resonated with the artistic energy of the Flemish Baroque masters. There, he continued his studies under his uncle, Jacob van Hal. Antwerp offered a rich environment for the young artist, exposing him directly to the powerful legacy of painters who had defined the previous century.

The influence of Antwerp, and particularly its Baroque heritage, cannot be overstated in shaping de Wit's artistic vision. He spent crucial formative years immersed in the city's artistic traditions. It was here that he encountered the works that would profoundly impact his style and subject matter throughout his career.

The Influence of Flemish Masters

While in Antwerp, Jacob de Wit deeply absorbed the influence of the towering figures of Flemish Baroque painting, most notably Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck. He dedicated time to studying their compositions, techniques, and thematic choices. This study was not merely academic; it was a practical engagement with their art.

A significant undertaking during his Antwerp period, around 1711-1712, involved sketching the ceiling paintings by Rubens in the city's Jesuit church (now St. Charles Borromeo Church). These original Rubens ceilings were tragically destroyed by fire in 1718, making de Wit's meticulous copies invaluable historical documents. This exercise provided him with firsthand experience in handling large-scale decorative compositions and complex allegorical programs, skills that would become central to his own practice. The dynamic movement, rich colour (even when translated into preparatory sketches), and dramatic flair of Rubens left an indelible mark on him.

Similarly, the elegance, refined portraiture, and religious pathos found in the works of Anthony van Dyck also resonated with de Wit. While primarily known for decorative work, de Wit's handling of figures often shows an awareness of Van Dyck's graceful style. His time in Antwerp solidified his connection to the grand traditions of Flemish painting, which he would later adapt to the tastes of his Dutch patrons.

Return to Amsterdam and Rise to Prominence

Around 1715 or 1716, Jacob de Wit returned to his native Amsterdam. Armed with the skills and influences acquired in Antwerp, he quickly established himself as a leading artist in the city. The Dutch Republic, particularly Amsterdam, had a wealthy merchant class and patrician elite eager to adorn their grand canal houses and civic buildings with sophisticated art. De Wit's talents were perfectly suited to meet this demand.

He became the go-to painter for large-scale decorative commissions. His work graced the interiors of numerous prestigious homes along Amsterdam's canals, as well as public buildings. He specialized in creating integrated decorative schemes, including expansive ceiling paintings, wall panels, overdoors (bovendeurstukken), and chimney pieces (schoorsteenstukken). His ability to work on a grand scale and tailor his art to specific architectural contexts made him highly sought after.

His patrons were typically affluent merchants, bankers, and regents who desired interiors reflecting their status and cultivated taste. De Wit provided them with art that was both impressive and imbued with classical learning and allegorical meaning, signalling the sophistication of the homeowner. He became a defining artist for the interior decoration of Amsterdam's elite during the first half of the 18th century.

The Signature Style: "Witjes" and Grisaille

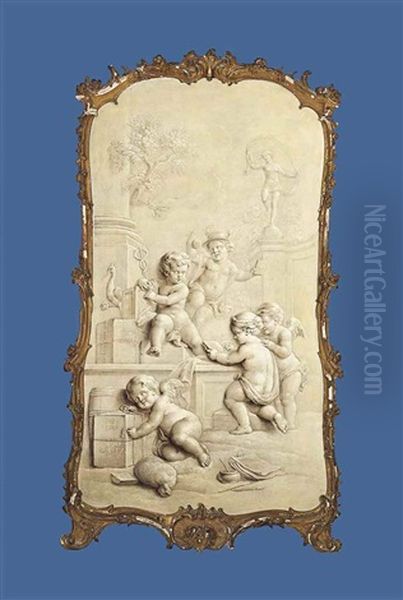

Jacob de Wit is perhaps most famous for his mastery of grisaille painting. This technique involves executing a painting entirely in shades of grey or other neutral colours, often to mimic the appearance of sculpture or relief. De Wit excelled at this, creating stunning illusions of marble or stucco reliefs, complete with convincing shadows and highlights that made the painted figures and ornaments appear three-dimensional.

His grisailles became so popular and distinctive that they acquired their own nickname: "Witjes," a playful pun on the artist's surname ("Wit" means "white" in Dutch) and the predominantly white or grey tones of these works. These "Witjes" were frequently used for overdoors, panels set into walls, and ceiling elements, often depicting putti (cherubic figures), allegorical scenes, or mythological subjects.

The appeal of his grisaille work lay in its elegance, technical brilliance, and its ability to integrate seamlessly with the Rococo interiors popular at the time. The style conveyed a sense of classical refinement and airy lightness, contrasting with the heavier, more colourful Baroque styles. De Wit's "Witjes" were highly admired and widely imitated, becoming a hallmark of Dutch interior decoration in the 18th century. His skill in this specific genre cemented his reputation as an innovator within the decorative arts.

Subject Matter and Major Themes

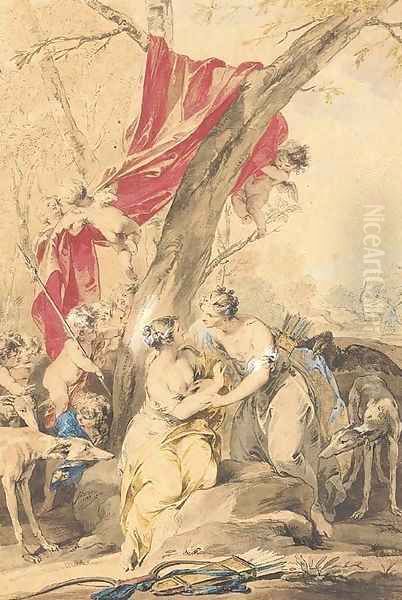

The subject matter in Jacob de Wit's oeuvre primarily revolved around mythological, allegorical, and religious themes, reflecting both the classical education of his patrons and the enduring traditions of history painting. He drew heavily from Greek and Roman mythology, depicting gods, goddesses, and narrative scenes often imbued with moral or allegorical undertones.

Allegory was a particularly favoured mode. De Wit created numerous series representing concepts like the Four Seasons, the Five Senses, the Times of Day, or virtues and vices. These allegorical figures and scenes were well-suited for decorative schemes in grand homes, providing visually pleasing compositions that also carried intellectual weight. They allowed patrons to display their learning and contemplate timeless themes.

Religious subjects also formed a significant part of his work. As a devout Roman Catholic, de Wit received commissions from Catholic patrons and institutions, including clandestine churches (schuilkerken) that existed discreetly in the predominantly Protestant Dutch Republic. He painted altarpieces, ceiling decorations, and other devotional works for these contexts. However, his reputation transcended religious divides, as he also undertook major commissions for Protestant civic institutions.

Representative Works

Several key works exemplify Jacob de Wit's style and importance. One of his most famous public commissions is the large canvas Moses Selecting the Seventy Elders, painted in 1737 for the Vierschaar (the tribunal room) of the Amsterdam Town Hall (now the Royal Palace on Dam Square). This work demonstrates his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions on a grand scale, drawing on biblical narrative for a subject relevant to governance and justice.

His decorative schemes in private residences are numerous, though many remain in situ or have been dispersed. Examples of his mythological paintings include works like Jupiter and Callisto, showcasing his skill in depicting narrative moments with Rococo grace. Allegorical series, such as the Allegory of Spring and Summer or the Allegory of the Five Senses, were common commissions for ceiling or wall ensembles. These often featured playful putti and idealized figures set against airy, cloud-filled skies.

His grisaille "Witjes" are perhaps his most iconic creations. Often depicting playful putti engaged in various activities related to the arts, sciences, or seasons, these works showcase his trompe-l'oeil mastery. Examples can be found in museums and historic houses, demonstrating the illusionistic sculptural effect he achieved with paint. Religious works like The Baptism of Christ further illustrate his versatility and his engagement with sacred themes, often rendered with a softness and elegance characteristic of his style.

Patronage and Religious Context

Jacob de Wit navigated the complex religious landscape of the 18th-century Dutch Republic with considerable success. As a Roman Catholic in a country where Calvinism was the official religion, his faith might have been expected to limit his opportunities. However, while he did receive important commissions from fellow Catholics, including decorating hidden churches like the Moses en Aäronkerk in Amsterdam, his talent and reputation earned him commissions from across the religious spectrum.

His most prominent patrons were the wealthy patrician families of Amsterdam, who commissioned extensive decorative cycles for their canal houses. These patrons valued his sophisticated, internationally-inflected style. Significantly, he also received major commissions from Protestant civic bodies, most notably the Amsterdam city government for the Town Hall painting of Moses. This demonstrates a degree of religious tolerance or pragmatism among the ruling elite, who prioritized artistic merit.

This ability to work for both Catholic and Protestant clients highlights de Wit's professional adaptability and the high regard in which his art was held. It suggests that while religious identity was important, artistic skill and the ability to deliver fashionable, high-quality decoration could bridge confessional divides, particularly within the cosmopolitan environment of Amsterdam. His uncle, Jacob van Hal, being a merchant and art collector, may also have provided crucial connections within the city's elite circles.

Connections and Artistic Network

Jacob de Wit operated within a rich artistic context, influenced by past masters and interacting with contemporaries. His network of connections is crucial to understanding his place in art history.

His primary teachers were Albert van Spiers in Amsterdam and his uncle Jacob van Hal in Antwerp. The most profound influences on his style were undoubtedly the Flemish Baroque giants Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, whose works he studied and copied extensively in Antwerp. The theoretical writings of Gerard de Lairesse, particularly his Groot Schilderboek (Great Book of Painting), which promoted a classicizing style, also informed the intellectual and compositional aspects of de Wit's work, especially his allegorical and historical subjects. De Lairesse's ideas were highly influential in the Netherlands during the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

Among his contemporaries, Cornelis Troost is often mentioned alongside de Wit as one of the leading Dutch painters of the 18th century. While Troost focused more on genre scenes and portraits, often with a satirical edge, both artists represented the pinnacle of Dutch painting during their time, albeit in different genres.

De Wit was not known to have formal apprentices in the traditional workshop sense. However, sources mention that he did impart some instruction to Johannes de Groot and Gerrit Dadelbeek. His main influence, however, was disseminated through the widespread admiration and imitation of his distinctive style, particularly his "Witjes."

Furthermore, de Wit was himself an art collector, owning drawings and possibly paintings by masters like Rubens. This collecting activity demonstrates his continued engagement with the art of the past. The broader context of Flemish art, including figures like Jacob Jordaens, also formed part of the Antwerp artistic milieu that shaped his early development. His work can be seen as a continuation and adaptation of this Flemish tradition, viewed through the lens of 18th-century taste, standing in contrast to the earlier Dutch Golden Age masters like Rembrandt van Rijn, whose style and subject matter were quite different.

Later Life, Legacy, and Collections

Jacob de Wit remained a highly respected and productive artist throughout his career. He never married and, as mentioned, did not maintain a large, formal workshop with numerous pupils. His influence spread primarily through the visibility and desirability of his finished works. He passed away in Amsterdam in 1754, leaving behind a substantial body of work.

An inventory taken after his death reportedly listed between 2,500 and 3,000 drawings and paintings in his possession. This vast collection, including his own works and potentially items he had collected, was auctioned in Amsterdam in 1755. The sale attracted considerable attention and dispersed his works, further spreading his influence. The proceeds, noted as 3,300 Dutch guilders, reflected the high value placed on his art.

Today, Jacob de Wit's paintings and drawings are held in numerous prestigious collections across the Netherlands and internationally. Major Dutch institutions like the Rijksmuseum and the Amsterdam Museum hold significant works. His paintings can also be found in the Mauritshuis in The Hague, and various municipal museums. Decorative schemes often remain in the historic canal houses for which they were created, some of which are now museums or public buildings. International collections, such as the Weimar State Art Collections in Germany, also house examples of his work, testifying to his historical importance.

Historical Evaluation and Influence

Jacob de Wit is firmly established as the leading decorative painter of the Dutch Rococo. He successfully adapted the grandeur of the Flemish Baroque, learned during his time in Antwerp, to the more intimate and elegant tastes of the 18th century. His work provided a sophisticated alternative to the styles of the earlier Dutch Golden Age, catering to a new generation of patrons.

His most distinctive contribution is undoubtedly his popularization and mastery of grisaille painting, the "Witjes" that became synonymous with his name. This technique, mimicking sculpture in paint, perfectly suited the light-filled, ornate interiors of the Rococo period and showcased his exceptional technical skill. His ability to create convincing illusions of three-dimensionality using only monochrome palettes was widely admired.

While he did not have a large school of direct followers, his style influenced decorative painting in the Netherlands throughout the 18th century. His work represents a high point in Dutch interior decoration, bridging the gap between the late Baroque and the emerging Neoclassical styles. He demonstrated that Dutch artists could still achieve excellence in large-scale, figure-based compositions, even after the Golden Age had passed.

His ability to work across religious divides and secure commissions from both Catholic and Protestant patrons speaks to his professional acumen and the universal appeal of his art. He remains a key figure for understanding the art and culture of the Netherlands in the 18th century, a period sometimes overlooked but one in which artists like de Wit maintained a high level of craftsmanship and aesthetic refinement.

Conclusion

Jacob de Wit carved a unique and influential path in 18th-century Dutch art. From his early training in Amsterdam and Antwerp, absorbing the lessons of the Flemish masters, he developed a distinctive style characterized by Rococo elegance and technical brilliance. His mastery of decorative painting, particularly his renowned grisaille "Witjes," transformed the interiors of countless Dutch homes and public buildings.

Though perhaps less famous internationally than the Dutch masters of the 17th century, de Wit was a dominant force in his own time. He successfully navigated the demands of his patrons, producing sophisticated mythological, allegorical, and religious works that defined the aesthetic of his era. His legacy endures in the numerous paintings, drawings, and decorative schemes preserved in museums and historic settings, securing his place as a master of Dutch Rococo decoration.