Jacobus Vrel stands as one of the most intriguing and mysterious figures of the Dutch Golden Age of painting. Active during the mid-17th century, his surviving body of work, though relatively small, offers a unique window into the everyday life and urban landscapes of his time, rendered with a distinctive, quiet introspection. For centuries, his identity was obscured, his works often misattributed to more famous contemporaries like Johannes Vermeer or Pieter de Hooch. However, modern scholarship has gradually unveiled Vrel as a distinct artistic personality, a painter whose enigmatic street scenes and tranquil interiors possess a haunting, almost surreal quality that sets him apart. This article delves into the life, art, and legacy of this elusive master.

The Shrouded Life of Jacobus Vrel

Pinpointing the exact biography of Jacobus Vrel remains a significant challenge for art historians. Unlike many of his contemporaries whose lives are reasonably well-documented through guild records, official appointments, or personal correspondence, Vrel seems to have moved through the bustling art world of the 17th-century Netherlands almost like a phantom.

The most widely accepted period for his activity is between roughly 1654 and 1662, based on the dates found on some of his paintings, notably his masterpiece, Woman at a Window, dated 1654. Some sources suggest his birth year around 1630 and his death around 1662, which aligns with this active period. There is, however, a less substantiated claim placing his death as late as 1680, though this finds little support in the broader scholarly consensus. The concentration of his dated works within that narrow 1654-1662 window strongly suggests this was his primary period of artistic output, or at least the period from which works have survived or been identified.

His name appears with frustrating infrequency in contemporary archives. Records in Amsterdam mention a "Jacobus Vrel" only twice, offering scant clues. Perhaps the most concrete historical mention comes from a 17th-century inventory: the collection of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria, a notable art patron, listed three paintings by Vrel. This indicates that, despite his current obscurity, his work was recognized and collected by discerning connoisseurs during his lifetime. The lack of guild memberships or other official records has led to speculation about his origins and where he primarily worked. While his style resonates with artists active in Delft, Haarlem, or Amsterdam, no definitive link to a specific city's artistic circle has been firmly established. This scarcity of biographical data contributes significantly to the mystique surrounding Vrel, forcing us to glean insights primarily from the visual evidence of his canvases.

Artistic Style: A World of Intimate Stillness

Jacobus Vrel's artistic signature is one of profound quietude and understated observation. He specialized in two main genres: intimate interior scenes, often featuring solitary female figures, and distinctive street views that feel both familiar and strangely deserted.

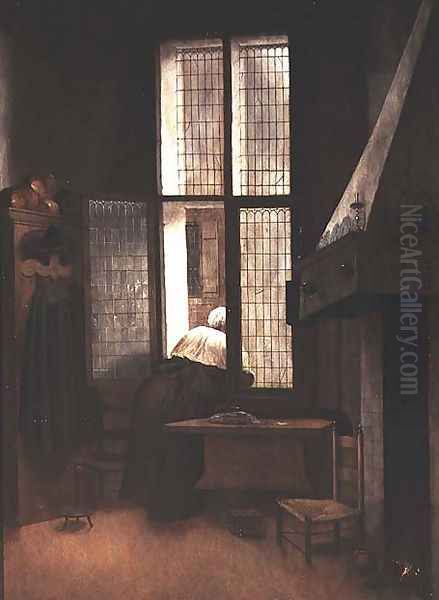

His interiors are characterized by their simplicity and a focus on the play of light in sparsely furnished rooms. Figures, typically women engaged in quiet domestic tasks or moments of contemplation, are rendered with a certain stiffness or peculiarity that adds to the enigmatic atmosphere. Unlike the more opulent or detailed interiors of artists like Gerard ter Borch or Gabriel Metsu, Vrel’s spaces are often humble, emphasizing a sense of containment and introspection. The light, usually soft and diffused, enters from a window, subtly modeling forms and creating a serene, sometimes melancholic mood. His palette tends towards muted earth tones, grays, and browns, punctuated by occasional touches of red or blue, contributing to the overall sense of calm.

Vrel's street scenes are perhaps his most original contribution. They are not grand cityscapes in the manner of Jan van der Heyden, nor are they bustling market squares like those by Adriaen van Ostade. Instead, Vrel presents narrow, often cobbled streets, lined with distinctive, sometimes slightly dilapidated, vernacular architecture. These scenes are typically sparsely populated, with a few figures engaged in quiet conversation or simply walking, their forms often small and somewhat anonymous. The perspective can be unconventional, sometimes slightly skewed or flattened, which imbues these urban vignettes with an almost dreamlike quality. He was a pioneer in this type of intimate urban landscape, predating or working concurrently with the early city views of artists like Daniel Vosmaer or Egbert van der Poel, but with a far more personal and less documentary vision.

A key element across his oeuvre is a palpable sense of stillness. Whether depicting a woman reading by a window or a quiet backstreet, Vrel captures moments of suspended time. This "Dutch Intimism," a term that could be applied to his work, emphasizes the private, the everyday, and the tranquil, creating a direct emotional connection with the viewer through shared, quiet human experience. His technique involved painting on wooden panels, a common practice, but his application of paint was often smooth, with careful attention to texture and the subtle gradations of light and shadow.

Representative Works: Glimpses into Vrel's World

While the total number of works confidently attributed to Vrel hovers around fifty, several stand out as quintessential examples of his unique vision.

Woman at a Window (1654), housed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, is arguably his most famous interior. It depicts a woman, her back partially to the viewer, gazing out of a leaded-glass window. The room is simple, with a chair, a small table, and a map on the wall – a common motif in Dutch painting, seen in works by Vermeer and Nicolaes Maes. The light streaming through the window illuminates the scene with a gentle glow, highlighting the texture of the woman's clothing and the quiet ambiance of the room. The composition is balanced and serene, inviting contemplation about the woman's thoughts and the world outside her window.

His street scenes are equally compelling. Works like Street Scene with People Talking or simply titled Street Scene (various collections, including one notably acquired by the Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung for the Alte Pinakothek, Munich) showcase his distinctive approach to urban environments. These paintings often feature narrow, winding streets, tall gabled houses, and a few isolated figures. The architecture is rendered with a charming, slightly naive precision, and the overall atmosphere is one of quietude, almost as if the bustling city has momentarily fallen silent. These scenes are not identifiable as specific locations, adding to their universal, almost timeless appeal. They differ markedly from the more topographically accurate cityscapes of contemporaries like Gerrit Berckheyde, focusing instead on atmosphere and a sense of enclosed community.

Other notable works include interiors with women tending to children, baking, or simply sitting by a hearth, each imbued with Vrel's characteristic stillness and subtle psychological intrigue. The figures in his paintings, while central, often seem absorbed in their own worlds, their faces sometimes obscured or turned away, enhancing the sense of mystery.

Vrel and His Contemporaries: Echoes and Distinctions

The art world of the Dutch Golden Age was a vibrant ecosystem of influence, competition, and shared thematic concerns. Vrel’s work inevitably invites comparison with several prominent contemporaries, most notably Johannes Vermeer and Pieter de Hooch.

The similarities with Vermeer are striking, particularly in their shared interest in solitary female figures in tranquil interiors, the masterful use of light, and even the initials "JV" (though Vrel's signature varies). For many years, particularly in the 19th and early 20th centuries when Vermeer himself was being "rediscovered" by critics like Théophile Thoré-Bürger, a number of Vrel's paintings were mistakenly attributed to the Delft master. However, careful stylistic analysis and dendrochronological dating of the wooden panels Vrel used have established that Vrel was likely active slightly before or concurrently with Vermeer's mature period. This suggests that Vrel was not an imitator of Vermeer, but rather an independent artist exploring similar themes, perhaps even acting as a precursor in some respects. While Vermeer’s interiors often possess a luminous clarity and compositional sophistication that is unparalleled, Vrel’s work offers a more rustic, sometimes more overtly mysterious interpretation of similar subject matter.

Pieter de Hooch, known for his sun-drenched courtyards and complex interior perspectives, also shares thematic ground with Vrel. Both artists depicted domestic life with a sense of order and tranquility. However, De Hooch’s figures are generally more robust and his spaces more clearly defined and architecturally elaborate than Vrel's often simpler, more enigmatic settings.

Vrel's style also shows affinities with a group of artists sometimes referred to as the "Delft School" or painters of "Dutch Intimism," even if his direct connection to Delft is unproven. Artists like Esaias Bourse and Pieter Janssens Elinga created similarly quiet interior scenes. Bourse, who actually travelled with the Dutch East India Company, painted intimate domestic scenes that share Vrel's unpretentious charm. Elinga, whose work was also sometimes confused with De Hooch's, specialized in sparsely furnished interiors with a strong emphasis on perspective and light, often featuring a figure seen from the back. Another contemporary, Quirijn van Brekelenkam, active in Leiden, painted humble interiors and workshop scenes that resonate with Vrel's focus on everyday life, though Brekelenkam's work often has a slightly more anecdotal character. Hendrick van der Burgh, whose works were also sometimes confused with those of De Hooch or even Vermeer, painted quiet domestic scenes that share a similar sensibility.

Despite these stylistic parallels, there is no concrete documentary evidence of direct collaboration or personal relationships between Vrel and these more famous masters. His unique stylistic quirks – the slightly elongated figures, the idiosyncratic perspective in his street scenes, and the pervasive sense of quiet melancholy – distinguish his work. He seems to have been an artist operating somewhat on the periphery, developing a highly personal vision. The fact that his works were collected by figures like Archduke Leopold Wilhelm suggests he had a market, but he did not achieve the widespread fame or leave the extensive paper trail of artists like Rembrandt van Rijn or Frans Hals.

The Enigma of Location and Influence

One of the enduring puzzles surrounding Jacobus Vrel is where he actually lived and worked. His street scenes do not depict identifiable Dutch towns in the way that, for example, Jan van Goyen's landscapes often do. The architecture in Vrel's paintings is somewhat generic, though it has a Northern European character. Some scholars have suggested that the buildings might reflect towns in the eastern Netherlands, or perhaps even German or Flemish border regions, due to certain architectural features. This ambiguity adds another layer to his enigmatic persona.

The question of who influenced Vrel is as complex as who he might have influenced. His interest in quiet interiors and street scenes places him firmly within the broader trends of Dutch genre painting. He may have been aware of the work of early Delft masters of perspective and interior scenes, or perhaps painters from Haarlem or Amsterdam who were exploring similar themes. The development of townscape painting was a gradual process in the Netherlands, with artists like Pieter Saenredam focusing on precise church interiors and Emanuel de Witte also depicting church interiors but with a greater emphasis on light and atmosphere. Vrel's street scenes, however, are more intimate and less monumental than the works of these architectural specialists.

His unique approach, particularly the slightly naive quality combined with sophisticated atmospheric effects, suggests an artist who was perhaps self-taught to some extent, or who deliberately chose to cultivate a style outside the mainstream academic conventions of the major artistic centers. This individuality is a core part of his appeal today.

Rediscovery and Re-evaluation in Art History

For a long period, Jacobus Vrel was largely forgotten, his works absorbed into the oeuvres of other, better-known artists. The process of his rediscovery began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as art historians and connoisseurs began to disentangle his hand from those of Vermeer, De Hooch, and others. This was part of a broader scholarly effort to understand the full spectrum of Dutch Golden Age painting beyond the most famous names.

The French art historian and critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger, instrumental in resurrecting Vermeer's reputation, also played a role in identifying other "minor masters." As more works by Vrel were correctly attributed, a clearer picture of his artistic personality began to emerge. Scholars like Clotilde Brière-Misme made significant contributions in the early 20th century to defining Vrel's oeuvre. She categorized him among the 17th-century "intimists," highlighting his focus on the quiet, personal aspects of daily life.

In recent decades, Vrel has garnered increasing scholarly attention. International research projects, including dendrochronological analysis of the wood panels he used, have helped to establish a more secure chronology for his work and to differentiate it more clearly from that of his contemporaries. Exhibitions, though rare, have helped to bring his work to a wider public. For instance, the Fondazione Custodia in Paris has been involved in promoting research and understanding of Vrel's art.

The acquisition of his Street Scene by the Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung for the Alte Pinakothek in Munich in 2018 was a significant event, underscoring his growing recognition as an important and distinct voice in Dutch art. His paintings are now found in prestigious museum collections worldwide, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Detroit Institute of Arts, The J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., and the aforementioned Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and Alte Pinakothek in Munich.

Artistic Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Jacobus Vrel's legacy is that of a highly original artist whose work offers a unique perspective on 17th-century life. His paintings are not grand historical narratives or ostentatious portraits; instead, they are quiet meditations on the everyday. His influence on his direct contemporaries is difficult to trace due to the lack of information about his life and interactions. However, his pioneering street scenes can be seen as an early exploration of a genre that would later be more fully developed by other artists.

The enduring appeal of Vrel's work lies in its enigmatic quality. His paintings invite viewers to step into a world that is at once familiar and strangely unsettling. The quietness of his scenes, the anonymity of his figures, and the slightly melancholic atmosphere create a powerful sense of mood. In an art historical period often characterized by meticulous realism and overt symbolism, Vrel’s work stands out for its psychological resonance and its almost modern sensibility. His paintings evoke a sense of solitude and introspection that speaks to contemporary audiences.

The art market has also recognized Vrel's rarity and unique appeal. His works command significant prices when they appear at auction, as evidenced by sales at major auction houses like Christie's. This market interest reflects a broader appreciation for his subtle artistry and his intriguing position within the Dutch Golden Age.

Conclusion: The Quiet Enigma

Jacobus Vrel remains one of the Dutch Golden Age's most captivating mysteries. An artist of quiet streets and hushed interiors, he crafted a world that is uniquely his own. While the details of his life may remain shrouded in obscurity, his paintings speak with a clear and distinctive voice. They offer glimpses into the soul of 17th-century Holland, filtered through a sensibility that is both deeply personal and strangely timeless. His ability to imbue ordinary scenes with a profound sense of stillness and mystery ensures his continued fascination for art lovers and historians alike. As research continues, perhaps more of Vrel's story will come to light, but even in his enigmatic state, he stands as a testament to the diverse and often surprising talents that flourished during one of art history's richest periods. His work reminds us that sometimes the most profound artistic statements are made not with a shout, but with a whisper.