James Digman Wingfield (1812-1872) stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of 19th-century British art. A versatile painter, he navigated various genres with considerable skill, leaving behind a body of work that captures the opulence of stately interiors, the charm of social gatherings, the gravity of historical moments, and the picturesque beauty of landscapes. His career unfolded during a period of immense social, industrial, and artistic change in Britain, and his paintings often reflect the tastes and preoccupations of the Victorian era. While perhaps not achieving the household-name status of some of his contemporaries, Wingfield's contributions to genre painting, historical illustration, and the depiction of contemporary events merit closer examination.

Early Career and Artistic Inclinations

Born in 1812, James Digman Wingfield embarked on his artistic journey during a time when the Royal Academy of Arts, founded under the patronage of King George III, was the dominant force in British art. Aspiring artists often sought training within its schools or through apprenticeships with established masters. While specific details of Wingfield's early training are not extensively documented, his subsequent work demonstrates a solid grounding in academic principles of drawing, composition, and colouring. He emerged as a professional artist in the 1830s, beginning a career that would span several decades.

His versatility was evident early on. Wingfield did not confine himself to a single specialization but explored various avenues of artistic expression. He was adept at portraiture, capturing the likenesses of his sitters, and also turned his hand to landscape painting, a genre that was experiencing a golden age in Britain with masters like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable redefining its possibilities. Furthermore, Wingfield developed a proficiency in wood engraving and etching, printmaking techniques that allowed for wider dissemination of images and were crucial for illustrative purposes in books and periodicals of the time.

The Allure of the Past: Historical and Costume Pieces

A significant portion of Wingfield’s oeuvre is dedicated to historical subjects and costume pieces, often evoking the perceived romance and elegance of earlier eras, particularly the Carolean period (the reign of Charles I and Charles II). This fascination with history was a common thread in Victorian art and literature, with artists and writers frequently looking to the past for inspiration, moral exemplars, or simply picturesque subject matter. Wingfield's depictions of courtly gardens, elegant fêtes, and figures in period attire resonate with a romantic sensibility.

His style in these works often shows an affinity with the French Rococo painter Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), whose fêtes galantes – scenes of amorous, idyllic outdoor entertainments – had a lasting influence on European art. Wingfield, like Watteau, populated his canvases with gracefully posed figures in lush settings, though perhaps with a more distinctly Victorian sentimentality and narrative clarity. Other French masters of the 18th century, such as Jean-Honoré Fragonard and François Boucher, had similarly explored themes of aristocratic leisure and refined pleasure, and echoes of their decorative elegance can be discerned in Wingfield's approach to such subjects. His painting The Ladies' Portrait Gallery at Hampton Court (1849) is a prime example, showcasing his ability to combine architectural detail with a lively grouping of figures in historical costume, evoking the atmosphere of a bygone era within a specific, recognizable setting.

Wingfield also tackled more specific historical or literary scenes, such as his interpretations of The Uffizi Venus or The Dying Michelangelo. These works demonstrate an engagement with the grand tradition of history painting, which, according to academic hierarchy, was considered the noblest genre. Such paintings required not only technical skill but also a degree of erudition, involving research into historical settings, costumes, and narratives. His contemporaries, like Daniel Maclise, were also known for their large-scale historical canvases, often depicting dramatic moments from British history or literature.

Chronicler of Stately Homes and Grand Occasions

Beyond romanticized historical scenes, Wingfield excelled in depicting the interiors of stately homes and significant contemporary events. These works often combined meticulous architectural rendering with lively figural compositions, providing valuable visual records of Victorian life and its grand settings. His painting The Picture Gallery (1848), showcasing the art collection at Stafford House (now Lancaster House) in London, is a fine example of his skill in this area. Such paintings catered to a growing interest in the collections and lifestyles of the aristocracy and the newly wealthy.

Perhaps his most famous work in this vein is The Opening of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations (1851). This monumental event, housed in Joseph Paxton's revolutionary Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, was a defining moment of the Victorian age, celebrating British industrial and imperial power. Wingfield’s painting captures the grandeur of the occasion, with Queen Victoria presiding, and the vastness of the Crystal Palace teeming with dignitaries and visitors. The painting is a tour-de-force of detailed observation, conveying both the scale of the event and the excitement it generated. In its ambition and subject matter, it can be compared to the crowded contemporary scenes of William Powell Frith, whose paintings like Derby Day (1858) and The Railway Station (1862) became immensely popular for their vivid portrayal of Victorian society.

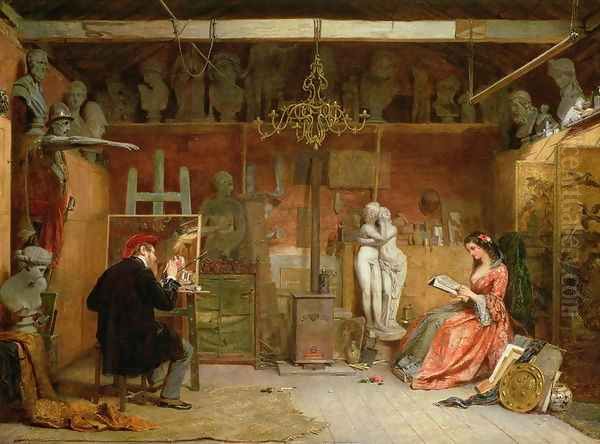

Another notable work, The Studio (1856), offers a glimpse into the artist's world, a popular theme in 19th-century art. Such paintings often served to elevate the status of the artist and provide insight into their creative process. Wingfield's depiction is rich in the accoutrements of a successful painter's workspace, filled with canvases, props, and objets d'art, reflecting both his practice and the prevailing aesthetic tastes.

Landscapes and Other Works

While celebrated for his interiors and historical scenes, Wingfield also produced accomplished landscapes. View of Kingston Bridge is one such example, demonstrating his ability to capture the specific character of a location with attention to light and atmosphere. The British landscape tradition was incredibly strong in the 19th century, with artists like David Cox and Peter De Wint producing evocative watercolors and oils of the British countryside. Wingfield's landscapes, though perhaps less central to his reputation, form part of this broader engagement with the national scenery.

His work The Wreck of the Firefly, Brighton indicates an interest in maritime subjects and dramatic events, a theme that also captivated Turner. The depiction of shipwrecks and storms at sea was a popular Romantic and Victorian trope, allowing for the exploration of themes of human vulnerability in the face of nature's power.

Wingfield's versatility extended to his technical approach. He worked primarily in oils, achieving a polished finish and a rich depth of colour. His compositions are generally well-structured, with a clear narrative or focal point. The attention to detail, particularly in costumes, furnishings, and architectural elements, is a hallmark of his style, aligning with the Victorian appreciation for meticulous realism.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and the "Digman" Question

Throughout his career, James Digman Wingfield was a regular exhibitor at prestigious London venues, most notably the Royal Academy of Arts and the British Institution. The Royal Academy's Summer Exhibition was, and remains, a crucial platform for artists to showcase their work, gain critical attention, and secure patronage. The British Institution, active from 1805 to 1867, also played a significant role in the London art world, providing an alternative exhibition space and promoting British art. Wingfield's consistent presence at these exhibitions indicates his active participation in the artistic life of the capital and the esteem in which his work was held. His paintings often commanded respectable prices, reflecting their appeal to Victorian collectors.

An interesting quirk related to his name has been noted by art historians. It is suggested that his middle name, "Digman," might have originated from a misspelling of "Dignam" in an early exhibition catalogue. Specifically, when he first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1836 with a work titled Portrait of a Lady, his name was reportedly recorded as "James Dignam Wingfield." Such clerical errors were not uncommon, and if this is indeed the case, the misspelled "Digman" seems to have stuck, becoming the name under which he was subsequently known and recorded, even in official documents after his death. This curiosity, while minor, adds a peculiar footnote to his biography. It's also noted that his surname, Wingfield, does not appear to connect him directly to the ancient and aristocratic Wingfield family, suggesting his lineage lay elsewhere.

Personal Life and Later Years

Details about Wingfield's personal life are somewhat sparse, as is often the case for artists who did not achieve the very highest echelons of fame or leave extensive personal archives. We know that he married Elizabeth Bois, and the couple had six children. Family life would have been a central aspect of his existence, providing a backdrop to his professional endeavors. During the 1840s, Wingfield and his family resided in Chelsea, a London district that was becoming increasingly popular with artists and writers. Later, they moved to a residence near Fitzroy Square, another area with strong artistic associations, having previously been home to artists like John Constable.

Wingfield continued to paint and exhibit throughout the 1850s and 1860s. One of his later collaborative works is The Picture Gallery at Somerly (1866), created with Joseph Rubens Powell. Collaborations between artists were not uncommon, particularly for large or complex commissions where different specializations could be combined. Powell (fl. 1835-1871) was a painter of architectural subjects and interiors, making him a natural partner for such a piece.

James Digman Wingfield passed away in 1872 at the age of 60. His death marked the end of a productive career that had contributed significantly to the Victorian art scene.

Artistic Style in Context

Wingfield's artistic style can be characterized as a blend of academic precision, Victorian narrative interest, and a romantic appreciation for the past. His meticulous attention to detail, particularly in rendering textures, fabrics, and architectural settings, aligned with the prevailing taste for realism championed by critics like John Ruskin, albeit Wingfield's realism was generally applied to more conventional and less morally charged subjects than those favored by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (e.g., John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti), who were his contemporaries.

His use of colour was typically rich and harmonious, contributing to the often opulent or picturesque quality of his scenes. Compositions were carefully planned to guide the viewer's eye and enhance the narrative or descriptive content of the painting. While influenced by earlier masters like Watteau, Wingfield adapted these influences to a Victorian sensibility, often imbuing his historical scenes with a degree of anecdotal charm or stately dignity. He was less of an innovator than a skilled practitioner who worked comfortably within established genres, refining them with his particular talent for detail and atmosphere.

Compared to the dramatic Romanticism of Turner or the profound naturalism of Constable, Wingfield's art is generally more illustrative and decorative. His historical scenes share some common ground with those of artists like Charles Robert Leslie or Augustus Egg, who also specialized in genre and historical subjects, often with a literary or anecdotal flavour. His grand interior views, such as those of picture galleries or state occasions, find parallels in the work of continental artists who specialized in similar subjects, like the detailed architectural views of Italian painters such as Canaletto from an earlier generation, or the interior scenes of the Dutch Golden Age masters like Johannes Vermeer and Pieter de Hooch, whose meticulous rendering of domestic spaces set a high bar for subsequent painters of interiors.

Legacy and Collections

James Digman Wingfield's legacy resides in his skillful and often charming depictions of historical and contemporary scenes, which provide valuable insights into Victorian taste and social life. His works are held in a number of significant public and private collections, a testament to their enduring appeal and historical importance. Institutions such as the Royal Collection Trust, the Royal Hospital Chelsea, the Courtauld Institute of Art, and the Government Art Collection in the UK hold examples of his paintings. The presence of his work in the Royal Collection is particularly noteworthy, indicating royal or high-level patronage during his lifetime or acquisition due to the historical significance of his subjects, such as The Opening of the Great Exhibition.

While he may not be as widely celebrated as some of his more revolutionary contemporaries, Wingfield's contribution to 19th-century British art is undeniable. He was a master of his craft, capable of producing works of considerable complexity and visual appeal. His paintings of stately homes, royal events, and historical vignettes continue to be appreciated for their meticulous detail, evocative atmosphere, and as historical documents in their own right. Art historians and enthusiasts of the Victorian era find in his work a rich source for understanding the period's aesthetics, social customs, and historical consciousness. His art serves as a window onto a world of elegance, ceremony, and romanticized history, painted with a skill that earned him recognition in his own time and ensures his place in the annals of British art. His influence can be seen in the continuation of detailed historical and genre painting, providing a counterpoint to the more avant-garde movements that would emerge towards the end of the 19th century.

In conclusion, James Digman Wingfield was a quintessential Victorian artist in many respects: industrious, skilled, and attuned to the tastes of his time. He adeptly navigated the demands of the art market, producing works that appealed to a broad range of patrons. From the intimate charm of The Studio to the public spectacle of The Opening of the Great Exhibition, his paintings offer a diverse and engaging vision of the 19th century and its relationship with the past. His dedication to capturing the intricacies of costume, the grandeur of architecture, and the nuances of social interaction ensures that his work remains a valuable and enjoyable part of Britain's artistic heritage.