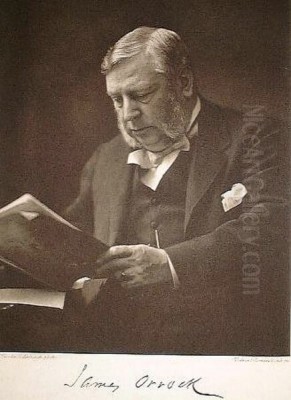

James Orrock stands as a fascinating figure in the landscape of 19th and early 20th-century British art. Born in Edinburgh in 1829 and passing away in 1913, his life and career were marked by a profound passion for art, manifesting not only in his own creations but also in his influential roles as a collector, dealer, and lecturer. Orrock's journey from a professional dentist to a dedicated artist and a pivotal figure in the art market of his time offers a compelling narrative of Victorian artistic life and patronage. His deep appreciation for the British school of landscape painting, particularly in watercolour, shaped his own artistic output and significantly influenced the tastes and collections of his contemporaries.

Early Life and the Call of Art

James Orrock's early life was rooted in the Scottish capital, Edinburgh, where he was born into a family with professional standing; his father was a respected dentist. Following in his father's footsteps, Orrock initially trained in dentistry, a profession he practiced with diligence for a number of years in Nottingham. This period of his life provided him with a stable foundation, but the allure of the art world proved increasingly strong. The mid-19th century was a vibrant time for the arts in Britain, with landscape painting enjoying particular favour, and Orrock was undoubtedly exposed to this burgeoning scene.

The pivotal moment in Orrock's career came in 1866 when he made the decisive move to London. This relocation was not merely a change of scenery but a fundamental shift in his professional focus. Leaving behind his established dental practice, he immersed himself fully in the pursuit of art. London, as the epicentre of the British art world, offered unparalleled opportunities for an aspiring artist: access to galleries, connections with fellow artists, and a market eager for new talent. This bold step demonstrated Orrock's commitment to his artistic calling, setting the stage for his multifaceted contributions to British art.

Artistic Development and Signature Style

Upon dedicating himself to art, James Orrock developed a style deeply rooted in the British landscape tradition. His primary medium was watercolour, a technique in which British artists had excelled for generations. Orrock's approach was significantly shaped by the work of earlier masters, most notably David Cox (1783-1859). Cox was renowned for his fresh, vigorous handling of watercolour, his ability to capture the fleeting effects of weather and light, and his evocative depictions of the British countryside, particularly Wales. Orrock absorbed these qualities, striving for a similar directness and atmospheric sensibility in his own paintings.

Orrock's subject matter predominantly featured the varied landscapes of Great Britain. He was particularly drawn to the rustic charm of the English countryside and the picturesque scenery of the Border Country between England and Scotland. His works often convey a sense of tranquil beauty, a romanticised yet carefully observed vision of nature. He was adept at capturing the nuances of light and shadow, the textures of foliage, and the expansive feel of open skies. His style can be described as a blend of realism, in its attention to natural detail, and a poetic sensibility that imbued his scenes with a gentle, often nostalgic, mood. This approach resonated with Victorian tastes, which often favoured art that was both representational and emotionally engaging.

Representative Works

Among James Orrock's notable works, several stand out as exemplars of his artistic concerns and stylistic strengths. Charnwood Forest, for instance, showcases his ability to render specific regional landscapes with both accuracy and atmosphere. This area in Leicestershire, known for its rugged, ancient terrain, provided ample inspiration for artists seeking the picturesque. Orrock's depiction would likely have emphasized its unique geological features and sylvan beauty, rendered with his characteristic attention to light and texture.

Other significant titles include Hay barge off Maldon, suggesting an interest in coastal and riverine scenes, where the interplay of water, sky, and human activity offered rich visual possibilities. Works like The Potato Harvest, Going to the Mill, and Gleaners point to his engagement with rural life and labour, themes popular in Victorian art that often carried connotations of pastoral simplicity and the dignity of agricultural work, echoing the spirit of artists like Jean-François Millet in France, though typically rendered with a less stark social realism by British painters. Twilight indicates his skill in capturing specific times of day, with the subtle gradations of colour and mood that accompany the fading light. These titles collectively paint a picture of an artist deeply connected to the British landscape and the rhythms of country life.

The Connoisseur and Collector

Beyond his own artistic practice, James Orrock carved out a significant reputation as an astute collector and dealer of art. His connoisseurship was particularly focused on British art, with a special emphasis on the watercolour school of the 18th and 19th centuries. He possessed a discerning eye for quality and a deep historical understanding of the artists whose work he collected and traded. This passion for collecting was not merely a private pursuit; Orrock became an influential figure in the art market, advising and selling to some of the most prominent collectors of his day.

His most notable client was the industrialist William Lever, 1st Viscount Leverhulme (1851-1925), the founder of Lever Brothers (now part of Unilever). Lever was an avid and ambitious collector, and Orrock played a crucial role in shaping his acquisitions. Between 1904 and 1912, Lever purchased a substantial portion of Orrock's personal collection, as well as many of Orrock's own paintings. This relationship was mutually beneficial: Orrock found a keen and wealthy buyer for his curated selections and his own art, while Lever gained access to high-quality works guided by Orrock's expert judgment. The fruits of this collaboration can still be seen today, particularly in the collection of the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight, which houses many pieces acquired through Orrock.

Orrock's activities as a dealer extended his influence on Victorian taste. He championed artists he admired, bringing their work to the attention of a wider audience and contributing to the appreciation of the British artistic heritage. His home often served as a gallery, filled with furniture, ceramics, and, of course, paintings, reflecting his broad aesthetic interests and creating an environment that itself promoted a particular vision of artistic living.

Influence, Collaborations, and the Artistic Milieu

James Orrock was an active participant in the artistic community of his time. He was a member of the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours (RI), a prestigious body that played a key role in promoting and exhibiting watercolour art. His involvement with such institutions underscores his standing among his peers and his commitment to the medium. He was also known as an engaging art lecturer, sharing his knowledge and enthusiasm with others, further contributing to the appreciation of British art.

His artistic practice was often enriched by direct engagement with fellow painters. Orrock frequently organized and participated in painting expeditions, travelling to various picturesque locations across England to sketch and paint outdoors. He shared these excursions with contemporaries whose artistic sensibilities aligned with his own, such as Claude Hayes (1852-1922), Thomas Collier (1840-1891), and Edmund Morison Wimperis (1835-1900). These artists, like Orrock, were dedicated to landscape painting, often working in watercolour and sharing an affinity for the stylistic legacy of David Cox. Such expeditions fostered a sense of camaraderie and allowed for the mutual exchange of ideas and techniques, a common practice among landscape artists who valued direct observation of nature.

Orrock's work and advocacy fit into a broader tradition of British landscape painting that included towering figures from earlier generations like J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and John Constable (1776-1837), whose innovations had profoundly shaped the genre. While Orrock's style was perhaps less revolutionary, he and his circle represented a continuation and popularization of this landscape focus. Other contemporary watercolourists who contributed to the richness of the Victorian art scene included Peter De Wint (1784-1849), though slightly earlier, whose broad, fluid style remained influential, Samuel Prout (1783-1852), known for his architectural subjects, and later figures like Myles Birket Foster (1825-1899) and Helen Allingham (1848-1926), who specialized in idyllic rural scenes. Even artists working primarily in oils, such as Benjamin Williams Leader (1831-1923), contributed to the prevailing taste for landscape. The critical writings of figures like John Ruskin (1819-1900) also played a significant role in elevating the status of landscape art and encouraging detailed observation of nature, creating a receptive climate for artists like Orrock.

Personal Life and Character

While much of James Orrock's public persona revolved around his artistic and commercial activities, glimpses of his personal life provide a more rounded picture. Born to James Orrock, a dental surgeon, and Elizabeth Orrock (née Scott), he maintained connections with his family. He married Sarah Lydia Woodman in 1853, and they had at least one daughter, Emma Lydia Orrock. His transition from dentistry, a profession also practiced by his father, to the less certain world of art, speaks to a strong inner conviction and passion.

Contemporaneous accounts and his own activities suggest a man of considerable energy and strong opinions. His role as a collector and dealer required not only a good eye but also business acumen and the ability to cultivate relationships with wealthy patrons. His lectures and writings on art indicate a desire to educate and to shape public taste according to his own well-defined principles, which championed the achievements of the British school. He was known for his advocacy of artists like Constable, Turner, and Cox, and his efforts to ensure their work was appreciated and preserved. His own home at 48 Bedford Square in London was a testament to his tastes, furnished with antiques and art, creating an environment that was both a private residence and a showcase of his connoisseurship.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

James Orrock remained active in the art world well into his later years. He continued to paint, collect, and deal, his reputation as a knowledgeable connoisseur firmly established. His influence extended through the many works that passed through his hands into private and public collections, most notably the substantial acquisitions made by Lord Leverhulme. These pieces, now in institutions like the Lady Lever Art Gallery, continue to reflect Orrock's taste and his role in preserving and promoting British art.

His own paintings are held in various public collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and regional galleries throughout the UK. While perhaps not considered in the very first rank of innovators like Turner or Constable, Orrock is recognized as a skilled and characteristic exponent of Victorian landscape watercolour painting. His work embodies the enduring appeal of the British countryside and the technical proficiency that marked the watercolour tradition.

The legacy of James Orrock is multifaceted. As an artist, he contributed a significant body of work that captured the beauty of the British landscape in a style that was both popular and respected in his time. As a collector and dealer, he played a vital role in the art market, shaping important collections and promoting the artists he admired. His advocacy for the British school, particularly figures like David Cox, helped to solidify their reputations. He was, in essence, a key cultural intermediary, bridging the gap between artists, patrons, and the public, and contributing to the rich tapestry of Victorian artistic life. His story highlights the interconnectedness of artistic creation, connoisseurship, and the market, and his influence can still be discerned in the collections he helped to build and the enduring appreciation for the art he championed.

Conclusion

James Orrock's career offers a compelling window into the Victorian art world. He successfully navigated the roles of artist, dental surgeon, collector, dealer, and lecturer, leaving an indelible mark on each field he touched. His dedication to the British landscape tradition, both in his own watercolours and in the works he championed, contributed significantly to its appreciation and preservation. His keen eye identified masterpieces and shaped the collections of influential patrons like William Lever, ensuring that future generations could experience the richness of British art. While his own paintings capture the serene beauty of the landscapes he loved, his broader impact lies in his passionate advocacy and his role as a custodian and promoter of an artistic heritage. James Orrock remains a significant figure, remembered for his artistic talent, his discerning connoisseurship, and his profound influence on the taste and collecting habits of Victorian and Edwardian England.