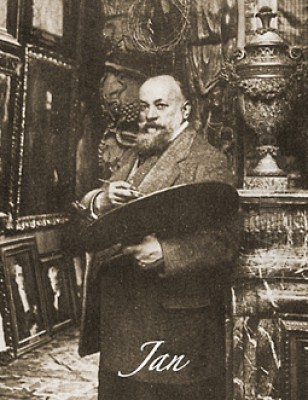

Jan Styka (1858-1925) stands as a monumental figure in Polish art history, a painter, illustrator, and poet whose ambition and talent led him to create some of the most expansive and emotionally charged artworks of his era. Renowned primarily for his colossal historical and religious panoramas, Styka's oeuvre captured the Polish national spirit, Christian devotion, and dramatic historical narratives with a distinctive blend of academic precision and romantic fervor. His life was one of artistic dedication, extensive travel, and a profound connection to the cultural and historical currents of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Lwów (then Lemberg in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, now Lviv, Ukraine) on April 8, 1858, Jan Styka was the son of an Austro-Hungarian military officer of Czech descent. This multicultural environment of Galicia, a region with a strong Polish cultural identity, undoubtedly shaped his early perspectives. His foundational education was received in Lwów, after which his artistic inclinations led him to the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Vienna, at the time, was a major European cultural capital, and its Academy was a bastion of academic art, emphasizing rigorous training in drawing, composition, and historical subjects.

However, it was his subsequent move to Kraków in 1882 that proved most formative for Styka's development as a historical painter. There, he became a student of Jan Matejko, the undisputed master of Polish historical painting. Matejko, known for his grand-scale depictions of pivotal moments in Polish history, such as The Battle of Grunwald and Sobieski at Vienna, instilled in his students a deep sense of national duty and the importance of art as a vehicle for preserving and promoting national identity. Styka absorbed Matejko's passion for historical accuracy, dramatic composition, and the portrayal of profound human emotion, elements that would become hallmarks of his own work. Other notable painters who were contemporaries or also influenced by Matejko's school included Jacek Malczewski, Stanisław Wyspiański, and Leon Wyczółkowski, though they each developed distinct styles.

The Panorama King: Chronicling History on a Grand Scale

Jan Styka's name became inextricably linked with the panorama, a hugely popular art form in the late 19th century that aimed to immerse viewers in a 360-degree painted scene. His most celebrated achievement in this genre is the Panorama of Racławice (Panorama Racławicka). Conceived to commemorate the centenary of the Battle of Racławice (1794), a significant Polish victory during the Kościuszko Uprising against Russian forces, the project was a massive undertaking.

Styka initiated the project and invited Wojciech Kossak, another prominent Polish battle painter from a renowned artistic family (son of Juliusz Kossak and father of Jerzy Kossak, both painters), to collaborate. The team expanded to include several other talented artists, such as Tadeusz Popiel, Zygmunt Rozwadowski, Teodor Axentowicz, Michał Sozański, Włodzimierz Tetmajer, and Wincenty Wodzinowski, with the German landscape painter Ludwig Boller also contributing. Each artist brought their specific skills to the enormous canvas, which measured an astounding 15 meters high and 114 meters long (originally 120 meters, but often cited with slight variations).

The Racławice Panorama was first unveiled in Lwów in 1894 for the General National Exhibition. It was an immediate sensation, lauded for its meticulous detail, dynamic portrayal of the battle, and its powerful evocation of Polish patriotism. The painting became a national treasure, a symbol of Polish resilience and aspiration for independence. Its journey, however, was not without challenges. Due to its anti-Russian themes and various political and financial difficulties, the panorama faced periods of being hidden or inaccessible. After World War II, with Lwów becoming part of Soviet Ukraine, the painting was eventually transferred to Wrocław, Poland, where, after extensive restoration, it was permanently housed in a specially constructed rotunda and opened to the public in 1985, remaining one of Poland's most significant cultural attractions.

Styka's ambition for panoramic painting did not end with Racławice. He was involved in other panoramic projects, including the Transylvanian Panorama (also known as Bem and Petőfi or Bem in Transylvania), depicting a scene from the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, which he also created with collaborators including Wojciech Kossak. This work, commissioned by the Hungarian government, further showcased his skill in managing large-scale, complex historical compositions. Fragments of this panorama have survived and are occasionally exhibited.

Devotion in Paint: Monumental Religious Works

Parallel to his historical epics, Jan Styka was a deeply religious man, and this devotion found profound expression in his art. He undertook pilgrimages to Italy and the Holy Land, experiences that further enriched his understanding and portrayal of Christian themes. His religious paintings are characterized by their dramatic intensity, emotional depth, and often, their monumental scale, rivaling his historical panoramas.

Perhaps his most famous religious work is The Crucifixion, also known as Golgotha. This colossal painting, measuring approximately 60 meters wide and 15 meters high (195 by 49 feet), was a labor of love and faith. The inspiration for this immense undertaking is said to have come from a dream recounted to Styka by his friend, the world-renowned Polish pianist and statesman, Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Styka envisioned a depiction of Christ's crucifixion that would be both historically accurate and overwhelmingly moving. He traveled to Jerusalem to sketch the actual site of Golgotha and meticulously researched historical details to ensure authenticity.

Completed in the late 1890s, The Crucifixion was exhibited in Warsaw, Kiev, and Moscow to great acclaim. In 1904, Styka brought the painting to the St. Louis World's Fair in the United States, hoping to find an American buyer. However, due to a dispute with his American partners over customs duties and exhibition fees, the painting was seized. For nearly four decades, its whereabouts were unknown, and it was feared lost. Miraculously, in 1944, the rolled-up canvas was discovered in the basement of the Chicago Civic Opera Company, severely damaged from years of neglect.

The painting was eventually acquired by the American businessman and cemetery developer Hubert Eaton, founder of Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California. Eaton commissioned Jan Styka's son, Adam Styka (also an artist), to undertake the painstaking restoration of the masterpiece. After years of meticulous work, The Crucifixion was unveiled in 1951 in a specially constructed building, the Hall of Crucifixion-Resurrection, at Forest Lawn, where it remains on permanent display, drawing visitors from around the world. Its sheer size and the emotional power of its depiction of the Passion of Christ continue to leave a lasting impression.

Other significant religious paintings by Styka include Peter in the Tomb (or St. Peter in the Grotto of St. Paul at Rome), which captures a moment of solemn reflection, and various scenes from the life of Christ, such as Christ Teaching His Disciples and the Multitude. He also painted works inspired by Henryk Sienkiewicz's novel Quo Vadis?, such as Quo Vadis, Domine?, depicting the legendary encounter between St. Peter and Christ on the Appian Way. These works further demonstrate his commitment to religious subjects, often rendered with the same dramatic flair and attention to detail found in his historical pieces.

Illustrator and Poet: Expanding Artistic Horizons

Beyond his monumental canvases, Jan Styka was also a talented illustrator and a poet. His skills as a draftsman were evident in his numerous illustrations, most notably for Henryk Sienkiewicz's Nobel Prize-winning novel, Quo Vadis?. Sienkiewicz, a towering figure in Polish literature, was a contemporary and acquaintance of Styka. Styka's illustrations for Quo Vadis? helped to visualize the dramatic scenes of early Christians in Nero's Rome, further popularizing the novel and cementing his reputation in the realm of literary art. These illustrations, often reproduced in various editions of the book, captured the novel's blend of historical drama and spiritual conflict.

His poetic endeavors, though less widely known than his paintings, offer another dimension to his artistic personality. They reflect his romantic sensibilities and his deep engagement with themes of history, faith, and national identity, mirroring the concerns prevalent in his visual art. This multifaceted creativity—painter, sculptor (though less emphasized in his career), illustrator, and poet—marks him as a versatile artist of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Travels, Later Years, and International Presence

Jan Styka was a cosmopolitan figure, and his artistic career involved extensive travel and periods of residence in various European cultural centers. After his initial studies, he spent time in Italy, particularly Rome, which was a crucial destination for artists seeking inspiration from classical antiquity and the masters of the Renaissance. His pilgrimage to the Holy Land also profoundly impacted his religious art.

He later settled in Paris around 1900, then the undisputed capital of the art world. Living and working in Paris allowed him to engage with contemporary artistic movements, although his style remained largely rooted in the academic and historical traditions. He was associated with the Polish artistic community in Paris, which included figures like Olga Boznańska. While in Paris, he continued to work on large-scale commissions and religious paintings. His presence in Paris also facilitated the international exhibition of his works.

Despite his international activities, Styka remained deeply connected to Poland. His art consistently addressed Polish historical and religious themes, reflecting a lifelong commitment to his cultural heritage. His sons, Tadeusz (Tade) Styka (1889-1954) and Adam Styka (1890-1959), also became painters, continuing the family's artistic legacy, with Adam playing a crucial role in the preservation of The Crucifixion.

Jan Styka spent his final years in Rome, a city that had long inspired him. He died there on April 28, 1925, and was initially buried in Rome. His contributions to Polish art and his role in creating iconic national and religious images ensured his lasting fame.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Legacy

Jan Styka's artistic style is best characterized as a late iteration of Academic Romanticism, with a strong emphasis on historical narrative and dramatic realism. His training under Jan Matejko was paramount, instilling in him a meticulous approach to historical detail, a flair for dynamic, multi-figure compositions, and a desire to convey powerful emotions and patriotic sentiment. Like Matejko, Styka saw art as a didactic tool, capable of educating and inspiring the nation.

His work shares affinities with other European academic painters of the 19th century who specialized in historical and religious scenes, such as Jean-Léon Gérôme in France or Hans Makart in Vienna, who also favored grandiosity and theatricality. However, Styka's Polish identity and his focus on national themes give his work a distinct character. His battle scenes are filled with movement and energy, while his religious paintings often convey a profound sense of spiritual intensity.

The panorama format, which he mastered, allowed him to create immersive experiences that were unparalleled in their scale and impact. These works were not just paintings but public spectacles that drew large crowds and played a significant role in shaping popular historical consciousness. Artists like Józef Brandt, another Polish painter known for his historical and battle scenes, particularly those related to 17th-century Polish history and often associated with the Munich School, also contributed to this tradition of national historical painting, though typically on smaller canvases than Styka's panoramas. Even earlier Polish Romantic painters like Piotr Michałowski had laid groundwork for the dynamic portrayal of horses and battle that later artists, including the Kossak family and Styka, would develop.

Jan Styka's legacy is multifaceted. He is remembered as a master of the panoramic form, a creator of iconic Polish national images, and a painter of deeply felt religious works. His paintings, particularly the Racławice Panorama and The Crucifixion (Golgotha), continue to be significant cultural landmarks, attracting thousands of visitors annually. He successfully combined technical skill, learned through rigorous academic training, with a romantic passion for his subjects, creating art that was both visually impressive and emotionally resonant.

His dedication to chronicling Polish history and Christian faith on such a grand scale ensured his place as one of Poland's most ambitious and recognizable artists. While artistic tastes evolved in the 20th century with the rise of modernism, Styka's work remains a testament to the power of academic historical painting and its capacity to capture the spirit of a nation and the enduring themes of human experience. His influence can be seen in the continued appreciation for narrative and historical art in Poland, and his major works stand as enduring symbols of artistic vision and national pride.